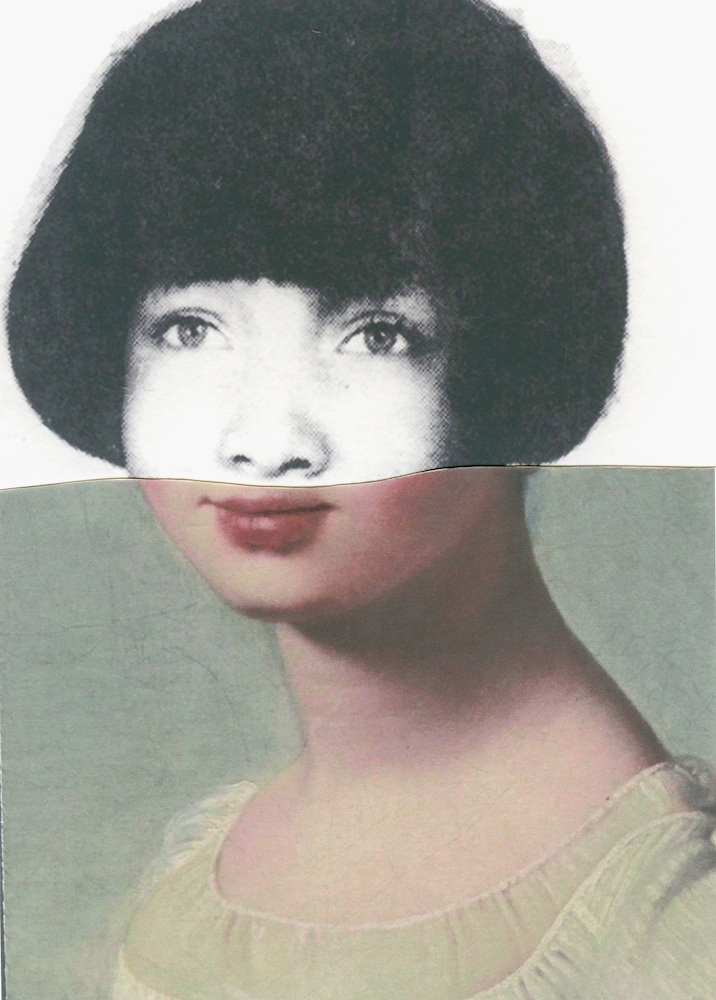

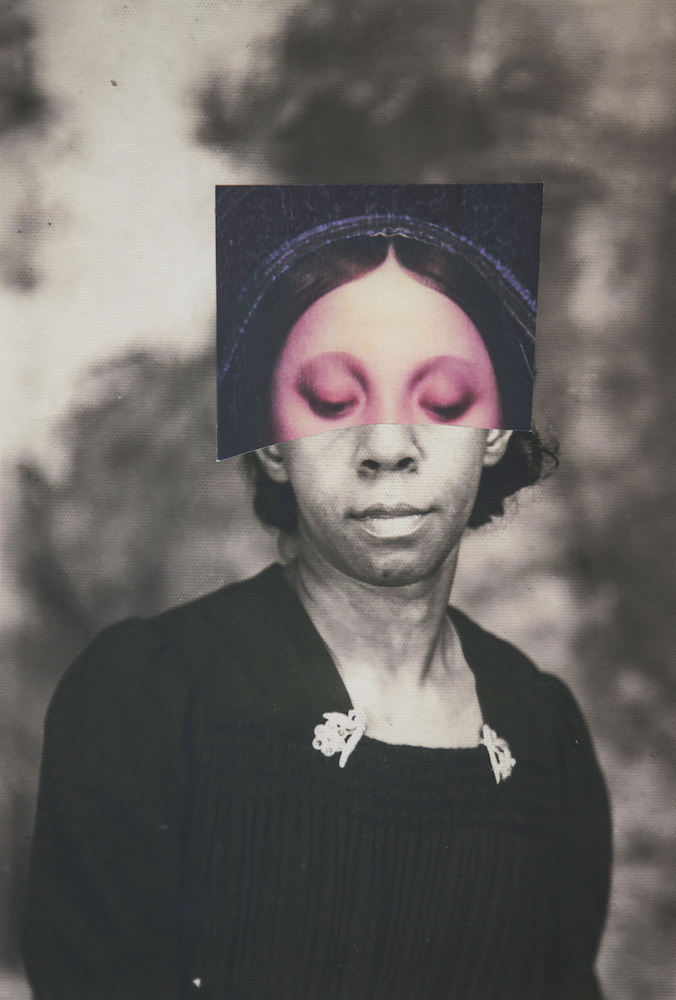

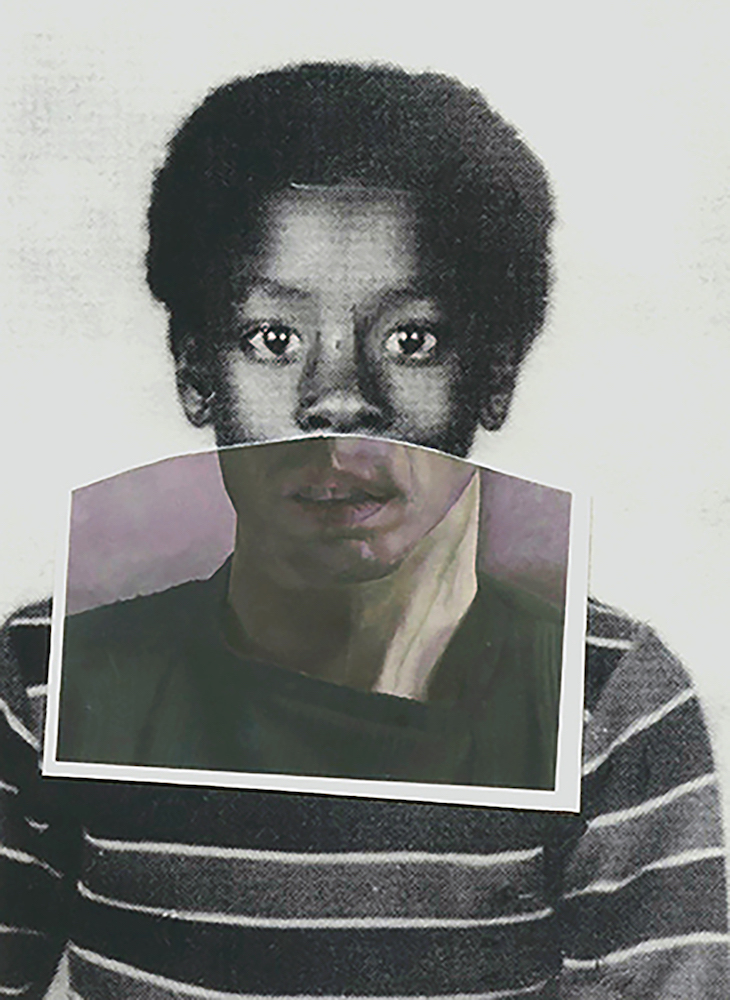

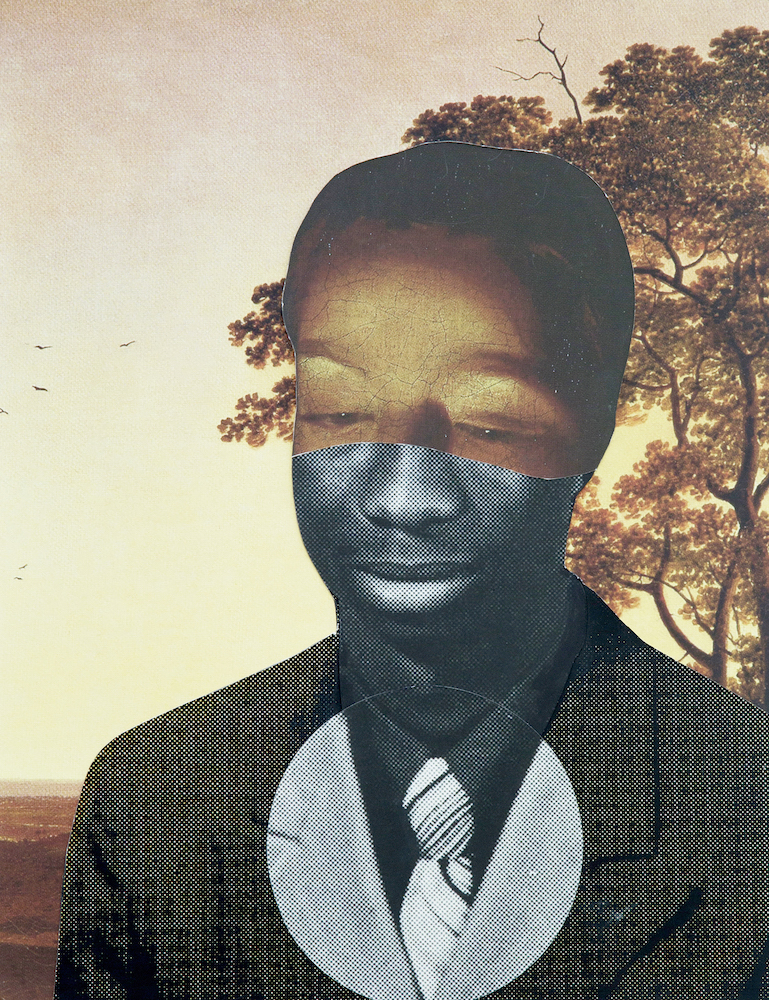

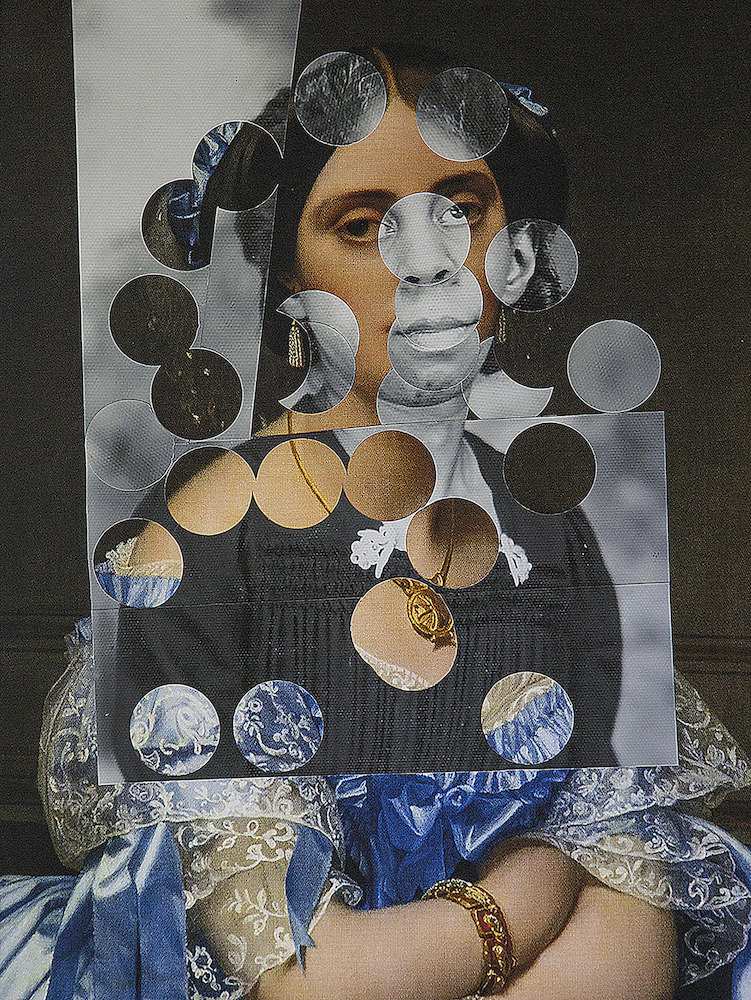

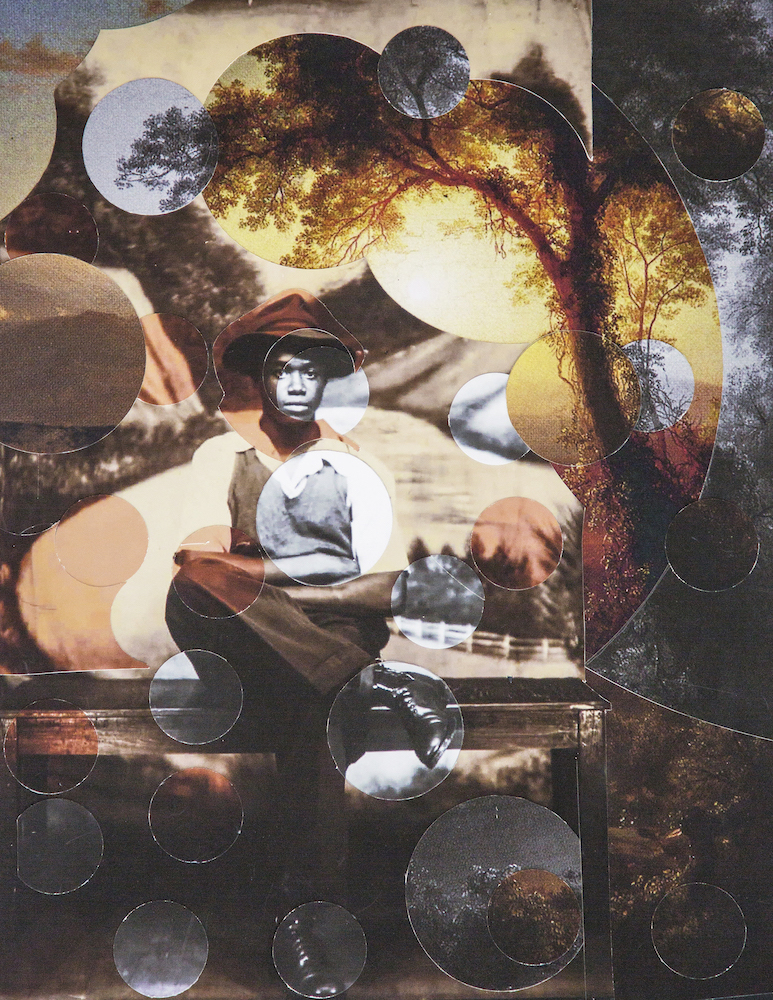

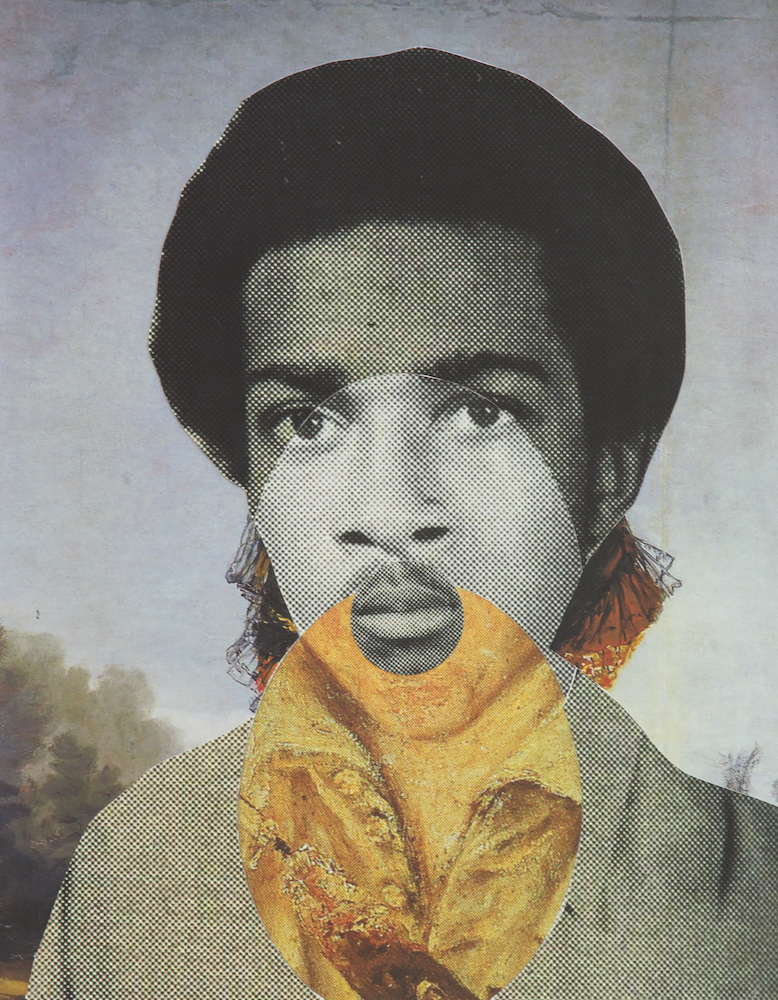

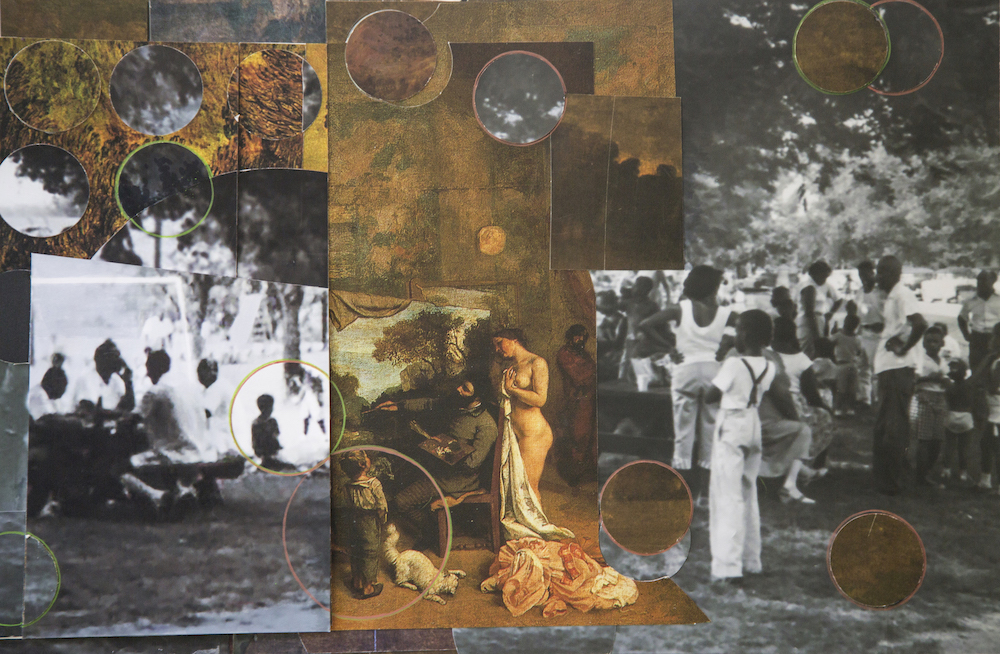

At first glance, Gary Burnley’s collages appear to be studies in dissonance. The Missouri-born artist takes photographs of Black subjects and uses them to overlay, paste over and undercut figures from classical European portraiture, employing a variety of shapes and lines to create what he calls a “conflation of optical rivalries”. Now showing at Elizabeth Houston Gallery in New York City, his exhibition In the Language of My Captor uses these disconnections to pose questions of form and framing, but also prompts the viewer into perceptive decisions: does affinity outweigh difference? And can commonality follow contrast?

The works are a continuation of Burnley’s interest in stereoscopes, the nineteenth-century, binocular-like contraptions which created an illusion of depth by positioning photographs side by side. In previous exhibitions, he has presented images in the devices, an in-situ deconstruction of his process. Here he focuses on how combination can prompt viewers to see works anew, as well as encouraging them to collapse the historical distance between pictures. “By putting images that didn’t really have that much to do with each other—at least initially—and then bringing them together, thoughts and ideas would begin to emerge,” Burnley explains. “And in their merging, there was some other kind of way in which they related to each other.”

The decision-making process is relatively organic, Burnley reveals, often hinging on tone or choreography, especially within the highly stylised tradition of portrait posing. In Young Lions, a portrait by the eighteenth-century English painter George Romney is reproduced in the foreground, while a photograph of three boys in youth club kit, or perhaps cadet uniform, stand tall behind. Common to the four figures are their direct stares, all unified in the knowledge that they are being captured for posterity.

“There’s something in that piece about the gesture of those boys,” Burnley explains, “something about the quality of their posturing that I thought went across time—across the contradictions that the images would seem to have—and brought them together in a way.” This focus on physicality emerges most clearly in the group images, where the emphasis falls on interrelation and setting rather than a single composite face. In What is Not So? a wedding photograph of child bridesmaids and grooms is coupled with a painting of opulent leisure, cherub-like figures reclining as their modern counterparts line up absentmindedly for the photographer.

“The images can never truly be reconciled. There’s a struggle in all the work”

“In almost all cases, it’s something that exists within my lifetime and within my realm of experience, and then something that exists in a realm of experience that I can only understand from this historical record that has been passed down,” Burnley explains of his selections. However, he is keen to emphasise the illusory nature of the “historical record” that is classical Western painting, exploring a tension between its representational capacity and that of photography. By manipulating aristocratic paintings by artists such as Jean-Auguste Ingres, Elisabeth Vigee Le Brun and Vigee Le Brun, the court painter of Marie Antoinette, Burnley participates in the undoing of the venerating style that defined the era.

“I think about photography as being much more closely related to ‘reality,’ or something that is more tangible,” he explains. Although within this his choice of yearbook and celebratory photographs also conjures similar questions around intention and aspiration. These images show their subjects at their best, momentarily transforming them into positive, conforming archetypes. Burnley is also conscious that repurposing images of African Americans carries its own creative responsibility: his work represents a retrospective empowerment, bringing these subjects into settings and conversations from which they have been historically excluded. “I’m interested in the historical root,” he says. “The centuries of ways in which those images have become ingrained in how we think about how we look at each other.”

Today’s racial discordances, in everyday life and pictorial representation, means that his works still exude a certain tension. “The images can never truly be reconciled,” he reflects. “There’s a struggle in all the work: sometimes it’s a little softer; sometimes it’s a little harder. But there’s a struggle because of the way that we are used to looking at images.”

Gary Burnley, In The Language of My Captor

At Elizabeth Houston Gallery until 24 April 2021

VISIT WEBSITE