View this post on Instagram

Picture this: while mindlessly scrolling on Instagram, you come across a targeted ad from Le Labo Fragrances. On a dark mahogany table sits a small cardboard box with rustically inscribed font. Below is a small apothecary style bottle of perfume, more akin to a tube you might find in a lab than that of a high-concept lifestyle brand. The caption reads: “Be careful what you set your heart upon—for it will surely be yours,” James Baldwin.

Would Baldwin have turned in his grave to know the Estée Lauder-owned luxury brand was employing lines from Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son (1961) to market their products? As a writer known for complex and eviscerating explorations of race and sexuality, what would he have thought about “#soulful fragrances” next to his name.

Or perhaps we are the dupes, targeted as part of a literary, upwardly mobile demographic, subject to algorithms touting chic, ascetic fragrances with an apparently revolutionary set of politics?

Such marketing isn’t just typical of skincare and beauty brands. The commercial adoption of literary and cultural figures is everywhere: Frida Kahlo phone cases, Sylvia Plath barbie dolls, Virginia Woolf finger puppets and Ruth Bader Ginsburg tea towels. This internecine commodification is all the more galling when we consider the radicalism or leftist politics of these figures: Kahlo was an avowed communist, after all.

From Drunk Elephant and Glossier to MAC and Maybelline, the skincare and beauty industries are thriving, with the global value of the market expected to top $750 billion by 2025. This boom goes hand-in-hand with the rise of this erudite marketing approach. The adoption of figures who lend cultural, intellectual, and perhaps even political cache to their brands is conducive to financial gain: recent studies by insight agency Protein show that 69% of consumers place ‘personal value alignment’ as the biggest deciding factor when purchasing from a brand.

Put bluntly? Intellectualising products makes money.

“Slapping a Jane Austen or Franz Kafka quotation on the side lends both pretension and gravity”

There are two dynamics operating here. Firstly, product areas seen as frivolous or shallow, and historically aligned with femininity, gain cultural ‘weight’: so slapping a Jane Austen or Franz Kafka quotation on the side lends an air of both pretension and gravity for objects typically aligned with women, in order to rewrite them as more serious.

And serious products come with serious price tags. A 100ml bottle of Le Labo’s Santal 33, with its minimalist label and plain brown paper box, costs upwards of £150. The branding, then, suggests those who buy the products share these literary, avant-garde and aesthetic-inclined interests. It’s the ultimate exercise in self-enhancement: easy cultural capital at the bottom of a make-up bag.

Has the radical and political act of caring for the self (coined as ‘self-care’ by Audre Lorde), become nothing more than a picture of Susan Sontag on a tube of hand lotion? Or is this penchant for literary aphorisms the ultimate corporate optimisation of self-knowing self-care? Self-care that is deracinated from its radical queer and feminist beginnings (colonised, packaged, commodified, flattened) and now seeks to upscale and rebrand the original messages and ideologies of artists in the guise of a radical, political act?

Take, for example, the Australian soap brand Aesop, who describe themselves as offering “utilitarian luxury” where “good writing permeates our approach to skincare”. With their own literary magazine and collaborations with queer writers, Aesop adorns their social-media posts with nods to highfalutin quotations from literary and artistic geniuses.

In a recent Instagram post we learn that: “From Émile Zola to Teju Cole, countless creatives have drawn inspiration from cities, and used art as a means of examining their societies. […] This is why the formulations in our Parsley Seed Skin Care range contain meaningful doses of fortifying ingredients.” Culture, it seems, is good for our skincare regimen.

“Has the act of caring for the self become nothing more than a picture of Susan Sontag on a tube of hand lotion?”

Orris Paris sell floral-scented artisanal botanical soaps for €60 apiece. Their Instagram reveals a similar proclivity for using images and quotations from literary, artistic and cultural figures to advertise their products. In one instance, they use New York artist and activist David Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (Face in Dirt)

, a photograph that was taken less than a year before Wojnarowicz died of AIDS-related illness, which sees the artist lying in a shallow grave, his face emerging from crumbling gravel.

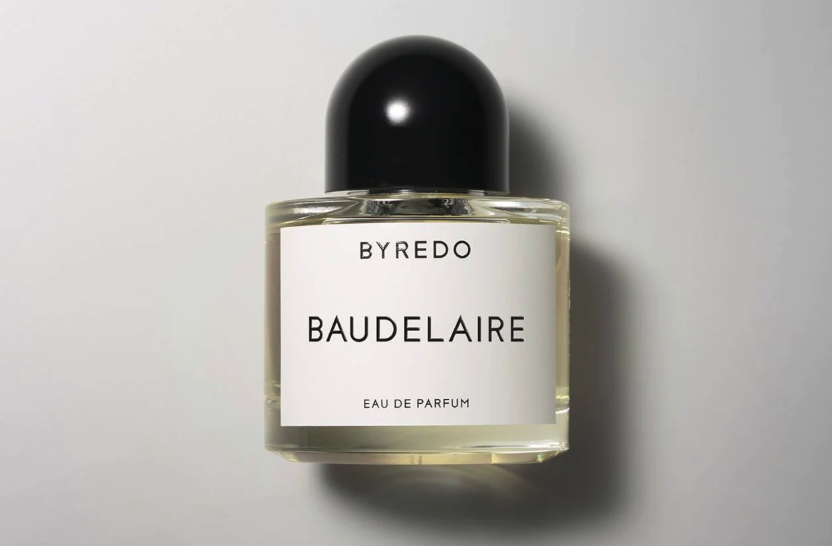

Meanwhile, Byredo’s Baudelaire Eau De Parfum, which sells for around £170 in the UK, is a homage to the “toxic poetry of the French symbolist writer”, where as in his most famous volume, The Flowers of Evil, “idle and eroticism intermesh in a vaporous haze”.

Then there’s feminist performance artist Cindy Sherman’s collaboration with MAC, Urban Decay’s Jean-Michel Basquiat makeup collection, or even skincare company Clarisonic’s baffling collaboration with Keith Haring. DKNY, NARS and Comme Des Garçons have produced Andy Warhol-related products, while luxury home accessories brand Ligne Blanche sell Warhol, Haring and Basquiat candles.

View this post on Instagram

Beyond the simple irony of anti-establishment and frequently anti-capitalist artists and writers being used to sell goods and make money for some of the world’s largest corporations, the contemporary co-option of these figures specifically flattens complex thought. It renders the work facile, sanitised and cleaned of grit.

Disruptive Black image-making like Basquiat’s becomes lipstick for white people and quotations from queer literary figures are used to sell androgynous gender-fluid pomades and hair tonics, with hashtags like #genderlessformulas adorning them.

We might think that brands looking for cultural gravitas alone would tend towards establishment figures over more radical, and provocative thinkers. However, while it’s true that capitalist logics consistently seek out new spaces to colonise—expropriating the value of what is ‘subversive’ or ‘cool’ faster than it can remain subcultural—there is more at play under the surface of their specific brand-fashioning.

“The contemporary co-option of these figures specifically flattens complex thought”

Many of these artists predominantly sat outside of the international art establishment during their lifetimes, or they actively rubbed up against the moral, conservative dictates of the time. We see artists and thinkers who created work that was not easily classified as ‘art’ at all, like Basquiat’s early work in graffiti duo SAMO and his wider critical reception (for example, critic Hilton Kramer described Basquiat as a “talentless hustler”).

Those chosen by these brands are typically a specific set of queer, often anti-establishment, artists, who lived and worked in a much grubbier and grittier New York than we know today, just prior to the AIDS epidemic, making disruptive, dirty, challenging art and writing, often about the AIDS crisis itself.

View this post on Instagram

The dilapidated Hudson pier waterfronts, the dark alleys off 42nd Street or the fetid underbelly of New York’s subway system seem fundamentally at odds with the aesthetic and purifying aims of luxury skincare and lifestyle brands. Ligne Blanches’ Keith Haring Red on White candle, with its £75 price tag, is the antithesis of Haring’s chaotic, explicit murals which speak to the sticky mess of queer pleasure, for instance.

The world that these artists were inhabiting and documenting was profane, feculent, sexy, and exhilarating. The Factory was renowned for how dirty it was. Basquiat spent most of his time in the penumbra of the city’s streets. Wojnarowicz, who writes in his memoir Close to the Knives, that he wants to ‘open up’ the body of his lover and to ‘feel the history of your flesh beneath my hands in a time of so much loss’, is chosen by a brand selling expensive soap.

“Turning commodities into works of art flattens, sanitises, and undoes the artworks they draw from”

Perhaps it’s no wonder that these beauty and lifestyle companies turn to this imagery and these reference points. In a competitive capitalist industry, this allows for brands to constantly redefine themselves: their spaces are not shops but high-end architecture; their marketing is not copywriting but literature; their products are not superfluous lifestyle objects but artworks.

Turning commodities into works of art flattens, sanitises, and undoes the artworks they draw from. Perhaps that’s the point: if these brands can sanitise and beautify even the grittiest documentation of a deadly epidemic, the most ardent and radical of voices, the grubbiest of artworks, then imagine what they’ll do for your pores.

At a time where people have turned to self-care in quarantine and where sanitisation, cleanliness and purity have become the thematic motif of our age, it’s telling that these two opposed aesthetics have become bedfellows.

Bryony White is a writer and academic. Leonie Shinn-Morris is head of editorial at Google Arts & Culture