“Tell me, dear, are you lonesome tonight?” So sang Elvis Presley in 1969 at the height of his fame, crowned by fans across America as the King of Rock ’n’ Roll. His lovestruck reveries struck a chord with millions, offering solace from the often-difficult realities of living in a country where rapid modernization came at a cost, with many subsisting below the poverty line despite the promises of the all-American dream. It is a scene that continues to resonate today, not only in divided America, while the King’s legacy lives on.

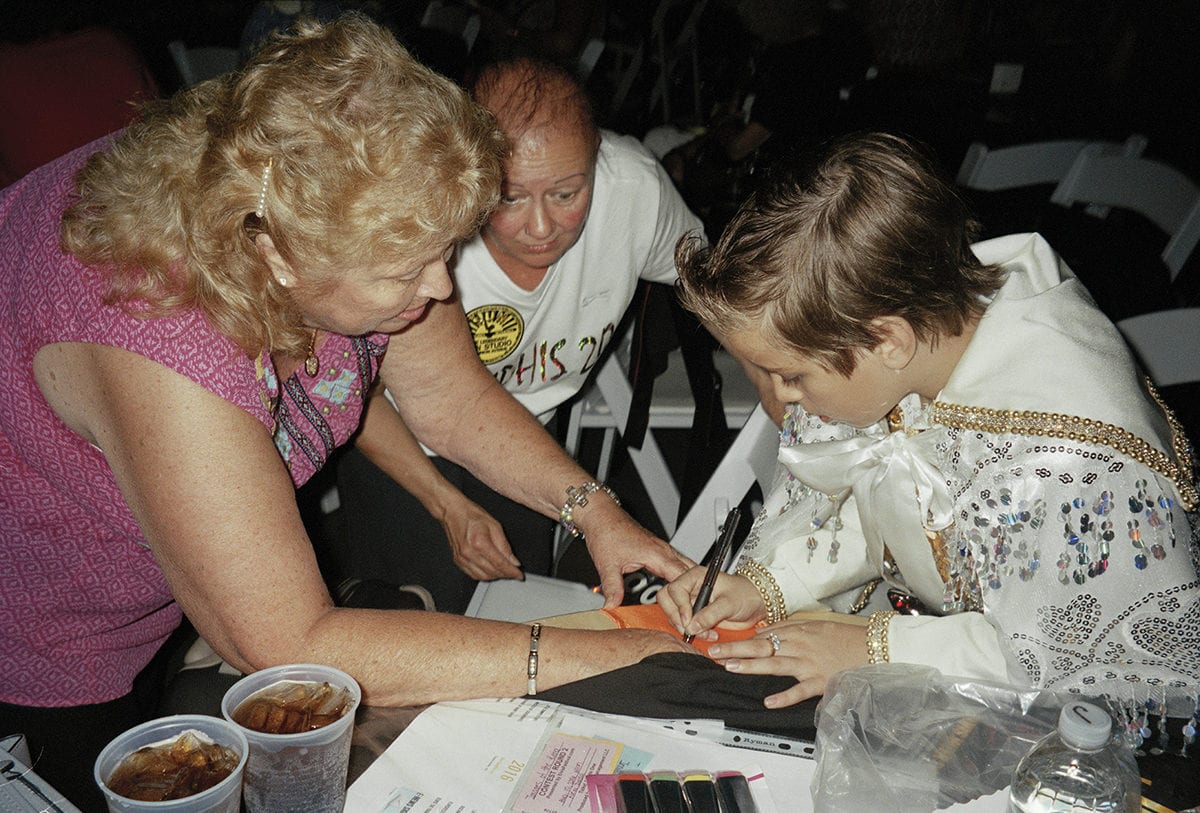

Between 2013 and 2017, French photographer Clémentine Schneidermann visited one of the world’s largest Elvis festivals in South Wales, as well as Memphis, Tennessee, documenting it in a series of images she later named I Called Her Lisa-Marie. Here, amidst bouffant wigs and tight white suits, she found this tension between fantasy and reality laid bare. Dreams of glitz and glamour mingle with kitsch memorabilia to melancholic effect, while portraits of a young Elvis impersonator who goes under the stage name Johnny B Goode reveal a lyrical, affirmative side to this escapism.

The transportative power of makeup, wigs, masks, special outfits and party dresses is a particular focus of yours. What interests you about the fantasy that can be built around these kinds of items?

My interest in costume comes from a foreigner’s perspective, really, because dressing up is very British—you don’t have it very much in France. The main thing that appealed to me when I arrived in the UK was this humour and eccentricity, and then when applied to Elvis it became almost a social project. What interested me was to go beyond the makeup and the costumes and to understand both the sadness and the poetry in this way of dressing up. It might have felt like these people were dressing up to have fun, but for them it wasn’t for a party. It wasn’t a one-off; it was their life.

- From the series Johnny B. Goode, 2016-2017

In your Elvis project, it can be difficult to distinguish between images taken in Wales and in Memphis. What was your experience of travelling in the two distinct places, and why did you want to mingle their sense of place in this way?

I started the project in Switzerland and then it moved to Wales, and then Memphis. It was always a very local project, focused on the community in the town where I was living at the time. The tension between fiction and reality was always at the core of the project. I think that if I had only done the project in Memphis it would have been quite easy, really. The light in Memphis is very different—it’s very sunny and hot—and I was looking at Jim Jarmusch’s Mystery Train, in which a young Japanese couple are travelling to Memphis and it’s quite weird and they’re very culture shocked; I liked this and wanted to explore it.

However for me the most interesting part was South Wales. It was about the region and the festival, which takes place each September in the small town of Porthcawl and is just dedicated to Elvis. It was about how these people often come from quite working-class backgrounds and they have this passion. The work was mainly made in the UK, and I spent most of the time in South Wales because that is where I lived for seven years. I became interested in America because its influence in the UK, particularly in working-class culture and popular culture, is very strong, but I was mainly inspired by Welsh culture and Welsh people.

“I wanted to go beyond the makeup and the costumes and to understand both the sadness and the poetry in this way of dressing up”

- From the series Johnny B. Goode, 2016-2017

What have been the challenges and the rewards of shooting portraits, particularly of children, while travelling in unfamiliar places?

Portraiture is one of the things that interests me the most. It’s a mystery; it’s intuition. There is a certain distance from people you need to retain. With the Elvis portraits, it doesn’t usually last more than five minutes—they’re often in the middle of doing something. I’m always looking for the natural gaze but it never feels quite sincere. In the Elvis project I was really inspired by people like Alec Soth and other documentary photographers. I was inspired by British social realism and American documentary, and balancing between the two continents. With children, you have to be very aware of how you represent them. Their relationship with the image and the camera is very different between each child, but it’s just them and it cannot be manipulated.

- Both images Clémentine Schneidermann and Charlotte James. Left: Nia, Gurnos, Merthyr 2018. Right: Over the Top, Gelligeg, Merthyr, 2017

You have gone one step further in recent projects and begun to dress up your subjects yourself, in collaboration with stylist Charlotte James. Why is this?

This theme of party dresses and dressing up is getting more and more important in my work—I guess it’s from a fatigue of looking at the same thing every day. When people start dressing up it’s kind of reinventing the real—it’s more attractive. When I am photographing people as they are dressed every day, I find it very difficult to find something interesting, but to dress them up in a normal urban environment is something very interesting to me. The clothes that I put in my work are from charity shops or eBay. These are not people who I am looking to cast, these are kids from the community.

It is a bit more staged, and I feel a lot of photographers are needing to stage these days. There’s no separation between fiction and reality. Dressing up is becoming a running theme in my work. I’m not thinking about it but I’m naturally drawn to these characters, people and imagery. It’s very unconscious.

“There’s no separation between fiction and reality. Dressing up is becoming a running theme in my work”

The architecture of place is very important in your images, especially in the post-industrial towns that you have visited in Wales. What do you think can be revealed in the interiors or exteriors of a space?

In the Elvis work I was often shooting in quite deprived areas in Wales, but that is where these people are living. I’ve got a few interiors of Graceland—the living room of Elvis, the recording studio—and then I also have the home of an Elvis fan with his suit hanging on the radiator. There is this contrast between the King and his fans. This kind of architecture strikes me… these places that are quite forgotten by other tourists. When you think of the UK you wouldn’t necessarily think of these places, but they are a big part of the country. I think it’s quite important to show that they exist and that this is how it is.

I’m quite inspired by British social realism; people like Ken Loach, although sometimes I find his films a bit much. There is a tradition of focusing on the social housing estate in both the photography and cinema of this period. I’m trying to rethink this representation and show it as less bleak and more poetic, and to uplift it. I don’t like the label of deprivation, and I don’t think it’s fair to talk about people like that. I do find these communities interesting, but my work is about much more than poverty. That is why I’m interested in costumes and how they can mix with the real.

All images © Clémentine Schneidermann, courtesy Sion and Moore

Clémentine Schneidermann, I Called Her Lisa Marie + Bonus Track

From 24 October to 3 November at Sion and Moore, London

VISIT WEBSITE