It’s not every day that an artist in their mid-nineties launches a Twitter account. Yet that is exactly what Herbert W Franke, with the help of his wife, journalist and media expert Susanne Päch, did on 8 March 2022. Franke introduced himself with a brisk “Hello World!”, followed by, “I am Herbert and I am a dinosaur of computer art.”

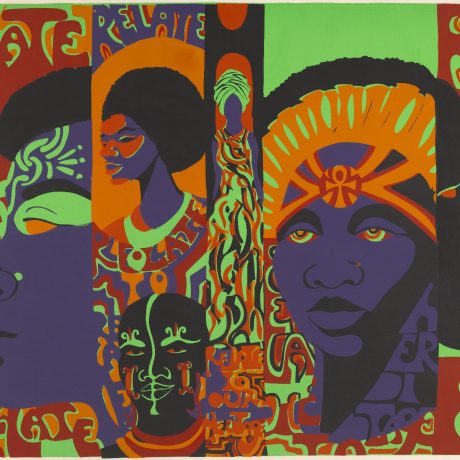

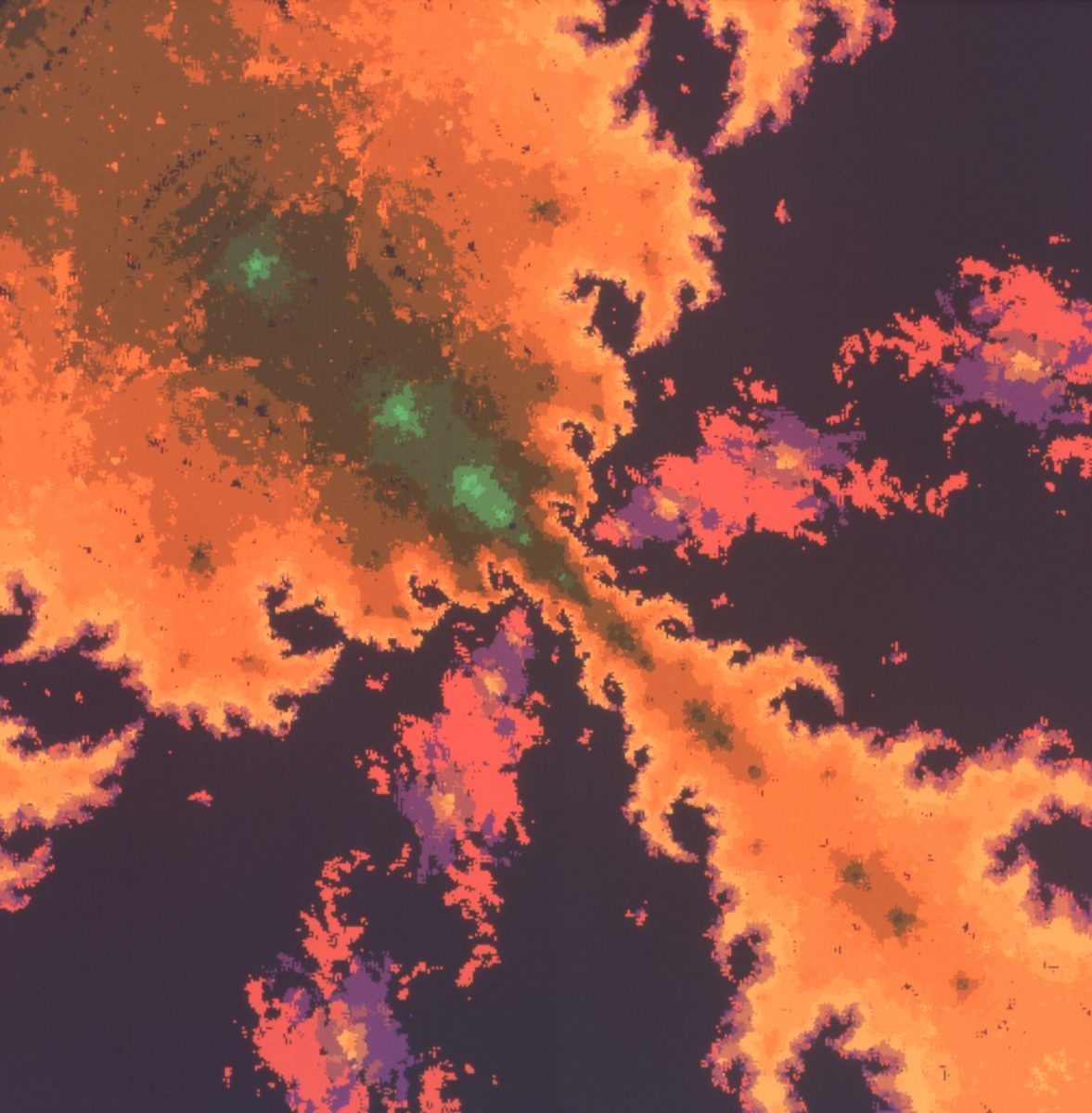

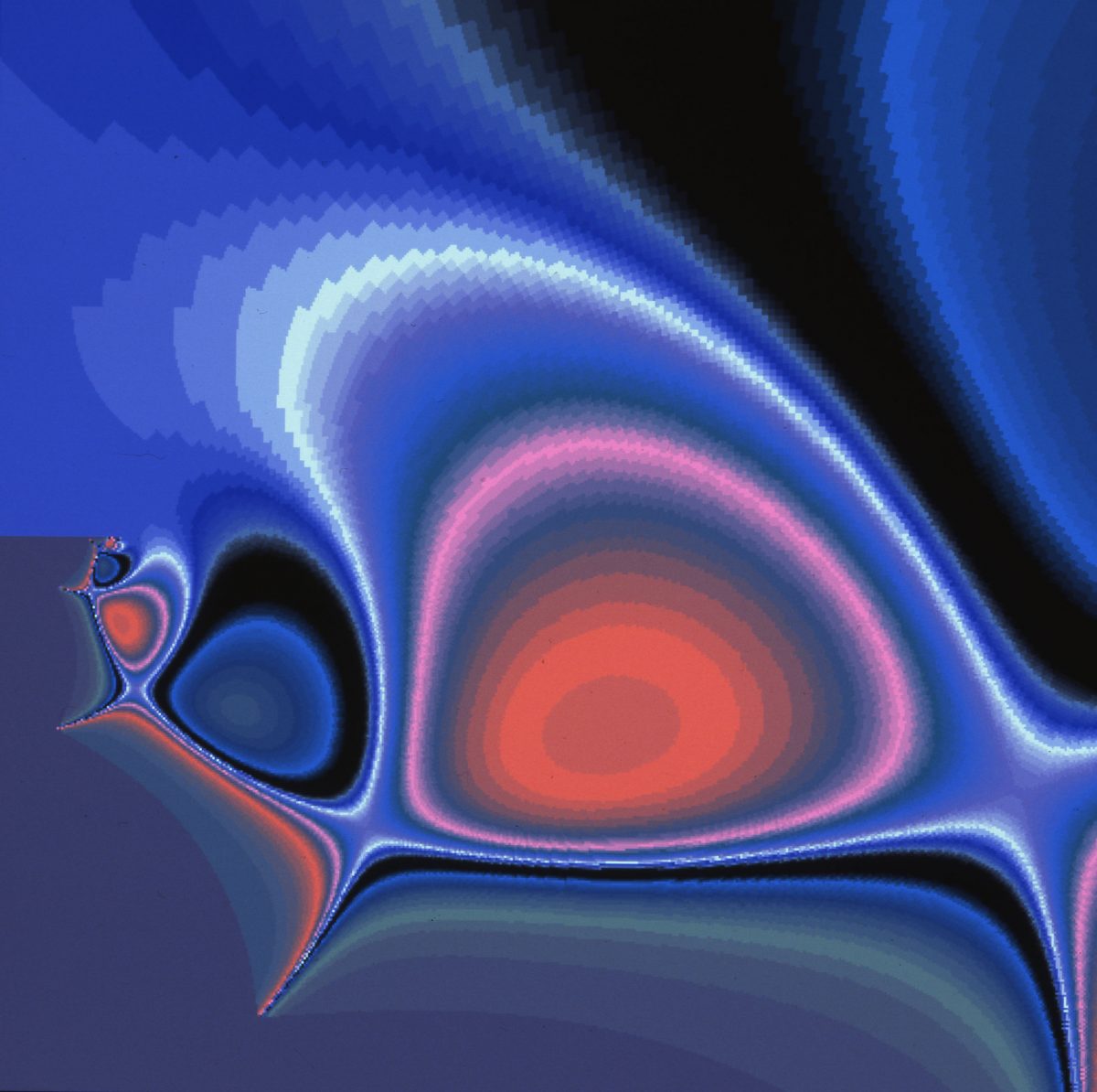

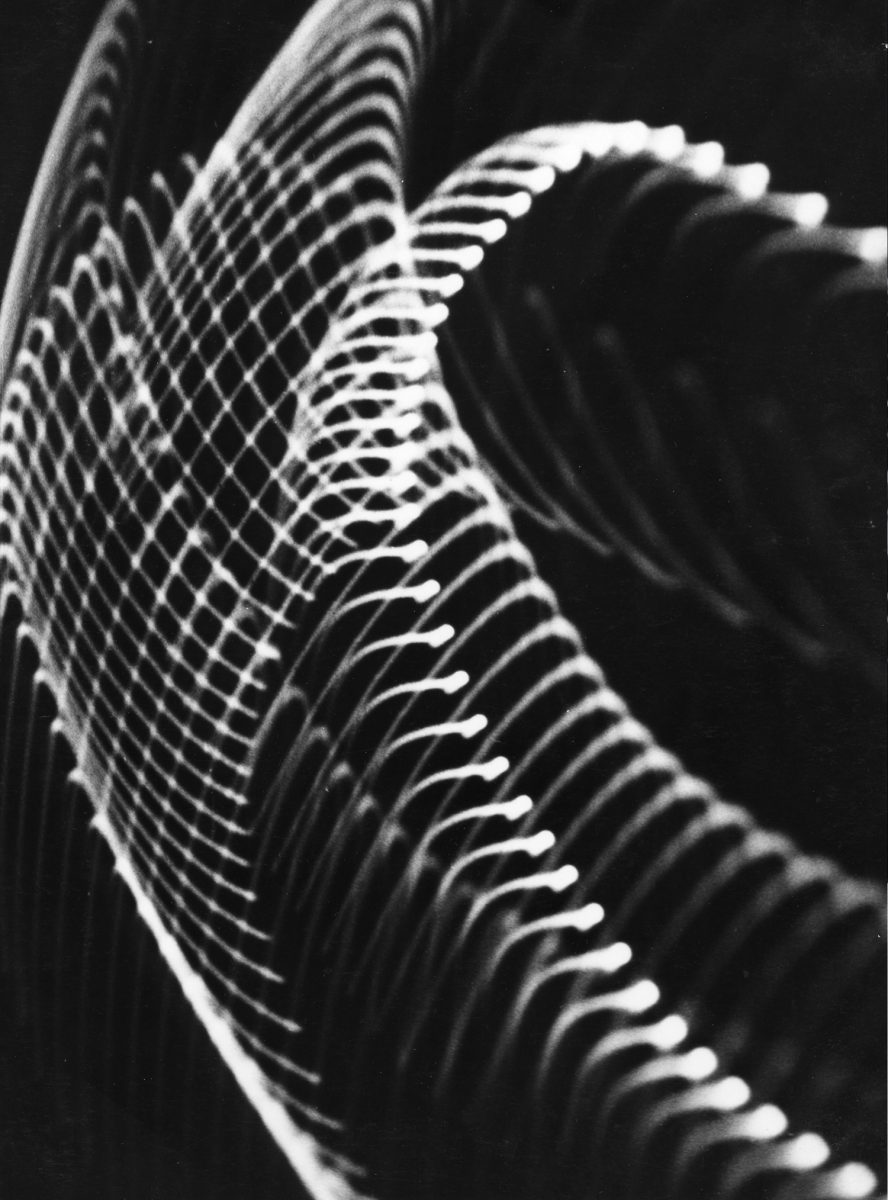

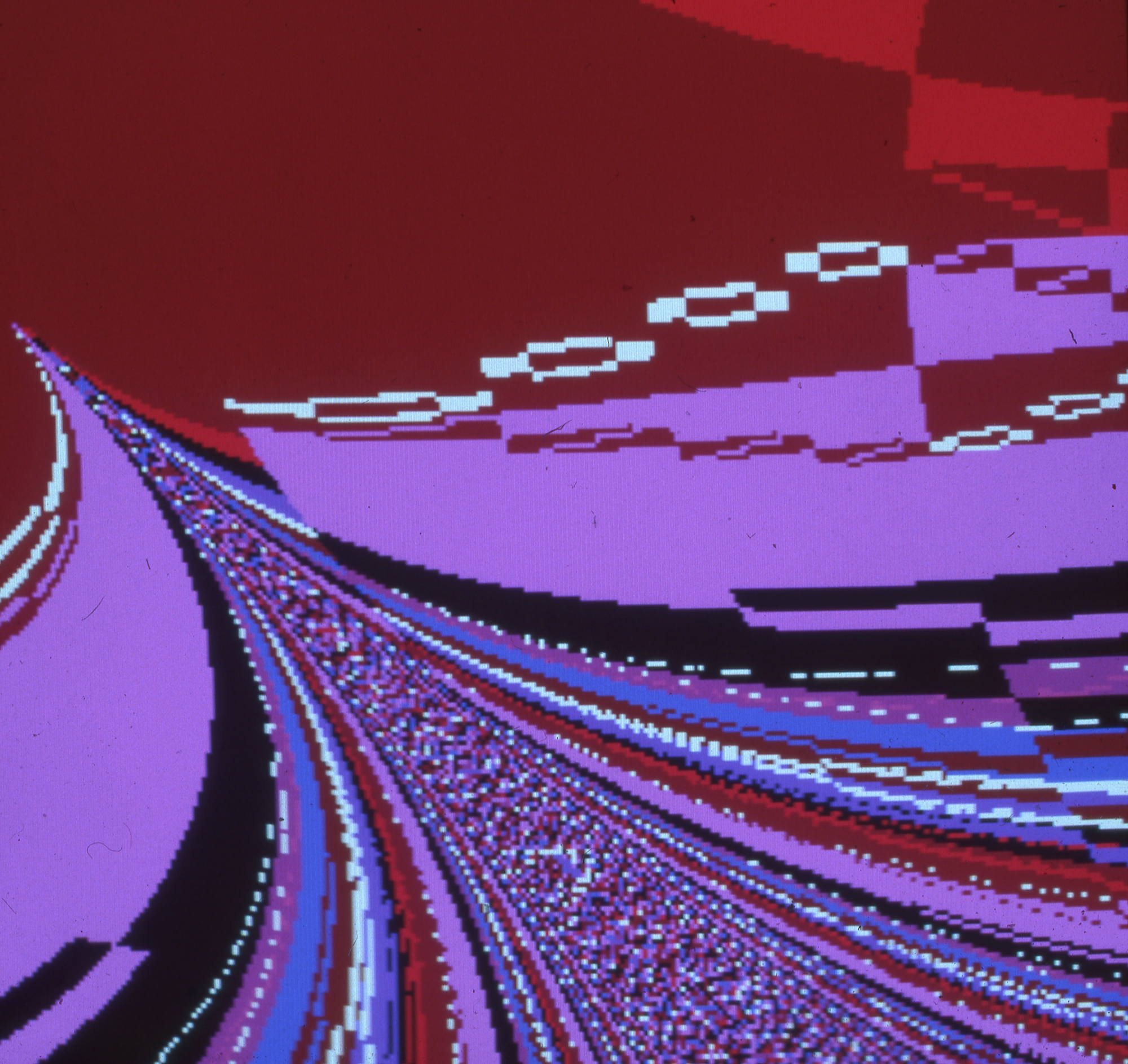

His inaugural tweet was illustrated with an image of one of his earliest pieces of computer art, made way back in 1954. His colleague Dr Franz Raimann built a simple analogue computer to calculate “multiple plane curves”, which were outputted graphically through a cathode-ray oscillograph. Franke photographed the screen, darkening the room and moving his camera back and forth to produce the multiple images seen in the final work. Inventing a hybrid process like this (analogue computer-oscilloscope-camera-printing) was a necessity at this stage in the development of postwar computing.

Franke’s tweet was a rallying-cry for an audience he didn’t know he had, and garnered thousands of likes. The first person to respond, AI artist Mario Klingemann, captioned a photograph of his collection of Franke’s published texts on computer art (worn and clearly much-read) with “Great to have you here. Your fanclub”. Later, as this “fanclub” continued to reveal themselves, Franke tweeted that he was “overwhelmed by your response”, adding the following day: “They told that I am still known in the modern scene. I was not so sure about this. But they told I should try an open an account. So here I am!” Within 48 hours he had amassed 10,000 followers.

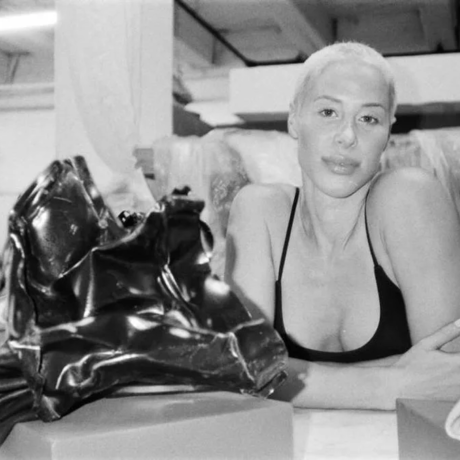

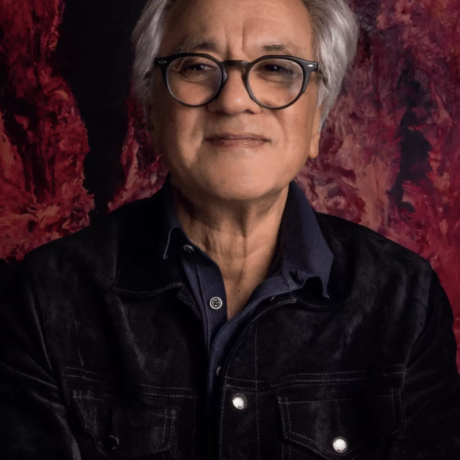

“Susanne has her eyes on Twitter all day long”, Franke explained via an interview conducted over email and facilitated by his wife, “I can’t do that anymore, but I try to be aware of everything that happens. It feels like back in the day when I was in touch with my artist friends, exchanging thoughts and ideas by mail.” The original impulse for Franke going public came from museum director Alfred Weidinger and writer/curator Anika Meier, who visited Franke before the opening of the artist’s current solo show, Visionary, at the Francisco Carolinum modern and contemporary art museum in Linz, the Upper Austrian city that also houses Ars Electronica, a showcase, research centre and festival of media and electronic arts co-founded by Franke in 1979.

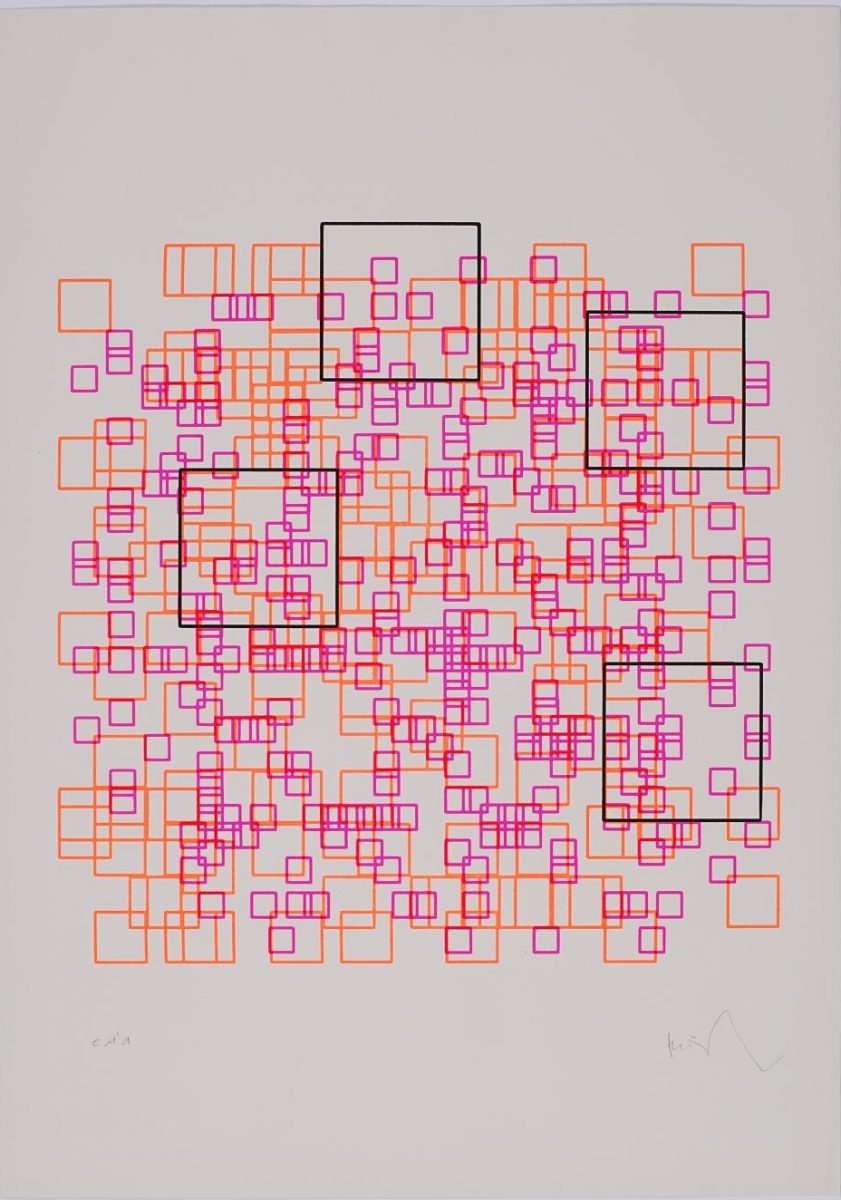

The Linz show is only the third major show of Franke’s career as an artist. 51 years passed between the first, in 1959 at the MAK museum of applied arts in Vienna, and at its successor, the ZKM Centre for Arts and Media in Karlsruhe. There were smaller and group shows in the interim, such as Computerkunst: Impulse, which the Goethe Institut turned into a travelling exhibition that toured some 200 cities worldwide in 1971-73. According to Päch, Franke was “exploring art like a scientist” and artworks were the outputs from his investigations; “Whenever there was a new technology, I felt the urge to apply math to find beauty.”

“Responses to his early art were not encouraging: ‘Your electrons are only virtually existing, you cannot touch them. This can’t be art’”

He began in the 1950s by moonlighting in the photo lab at Siemens, where he was employed in the advertising department, experimenting with “generative” abstract photographic images. Responses to his early art were not encouraging: the co-founder of the Ulm School of Design, Ottl Aicher, told him “Your electrons are only virtually existing, you cannot touch them. This can’t be art.” A turning point came in 1959 when the art historian Franz Roh urged Franke to write and publish his first book, Art and Construction: physics and mathematics as a photographic experiment, and to call his work art.

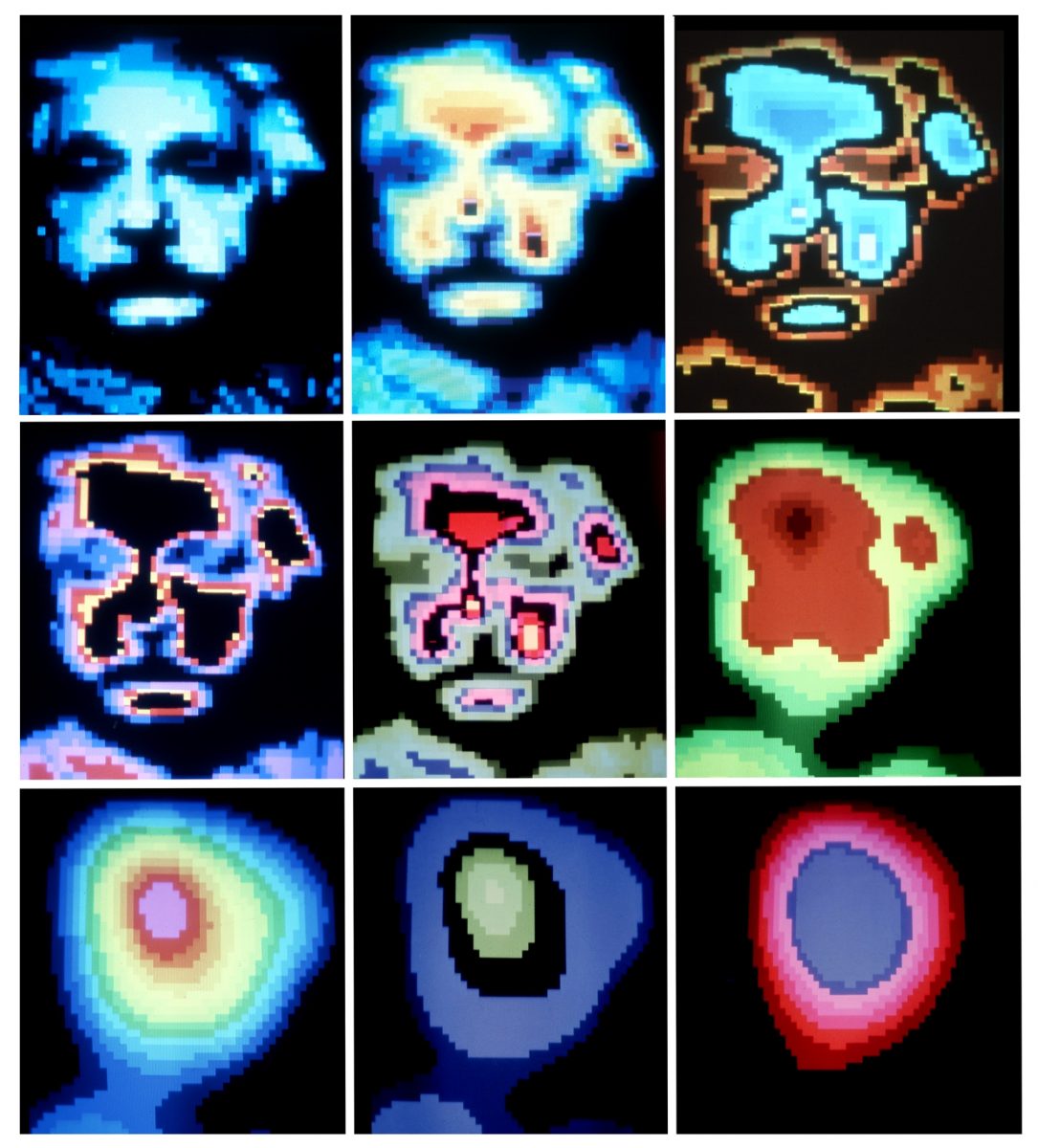

Franke’s experimentation went fully digital with the advent of mainframe computer. Large and expensive, they were hard to access, but cannily, he secured downtime on the mainframe at the Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry in Munich, and made the Math Art series at the German Aerospace Centre in Cologne, where his friend Horst Helbig had access on weekends. The advent of the personal computer in the late 1970s finally gave Franke an individual source of powerful digital technology, liberating him to write his own software programmes and algorithms.

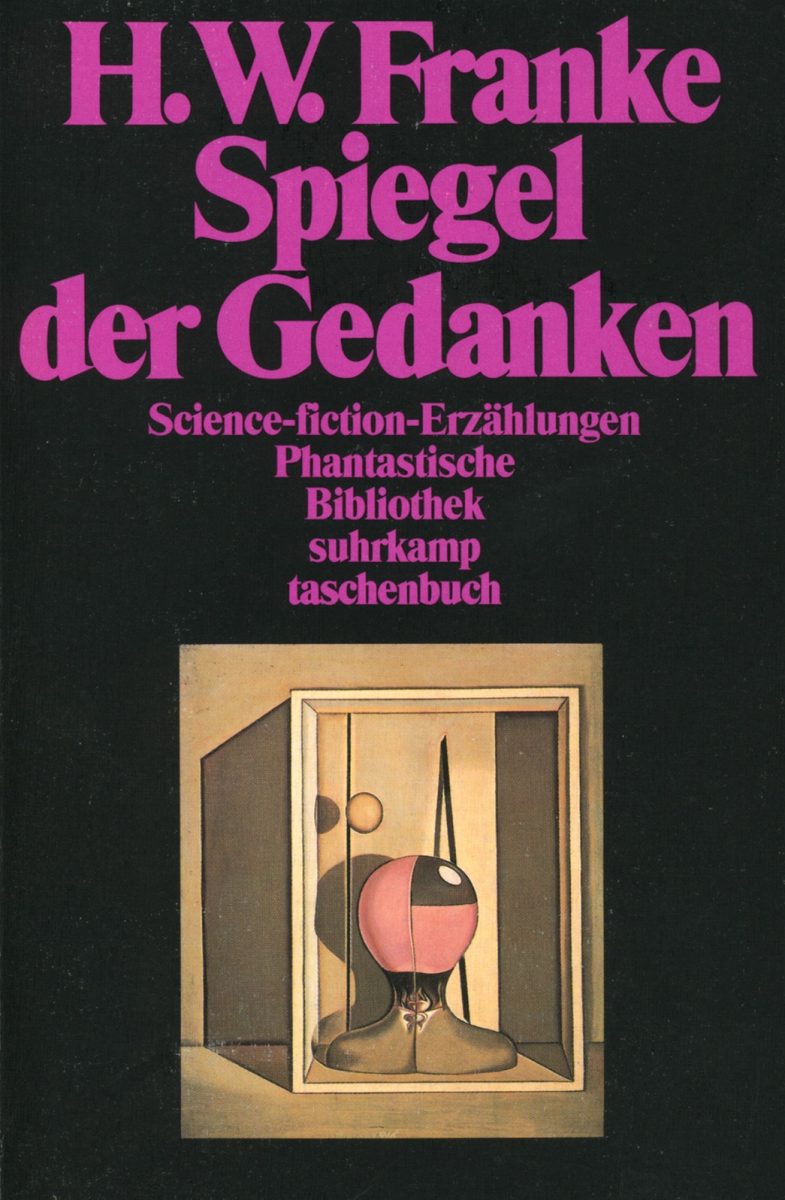

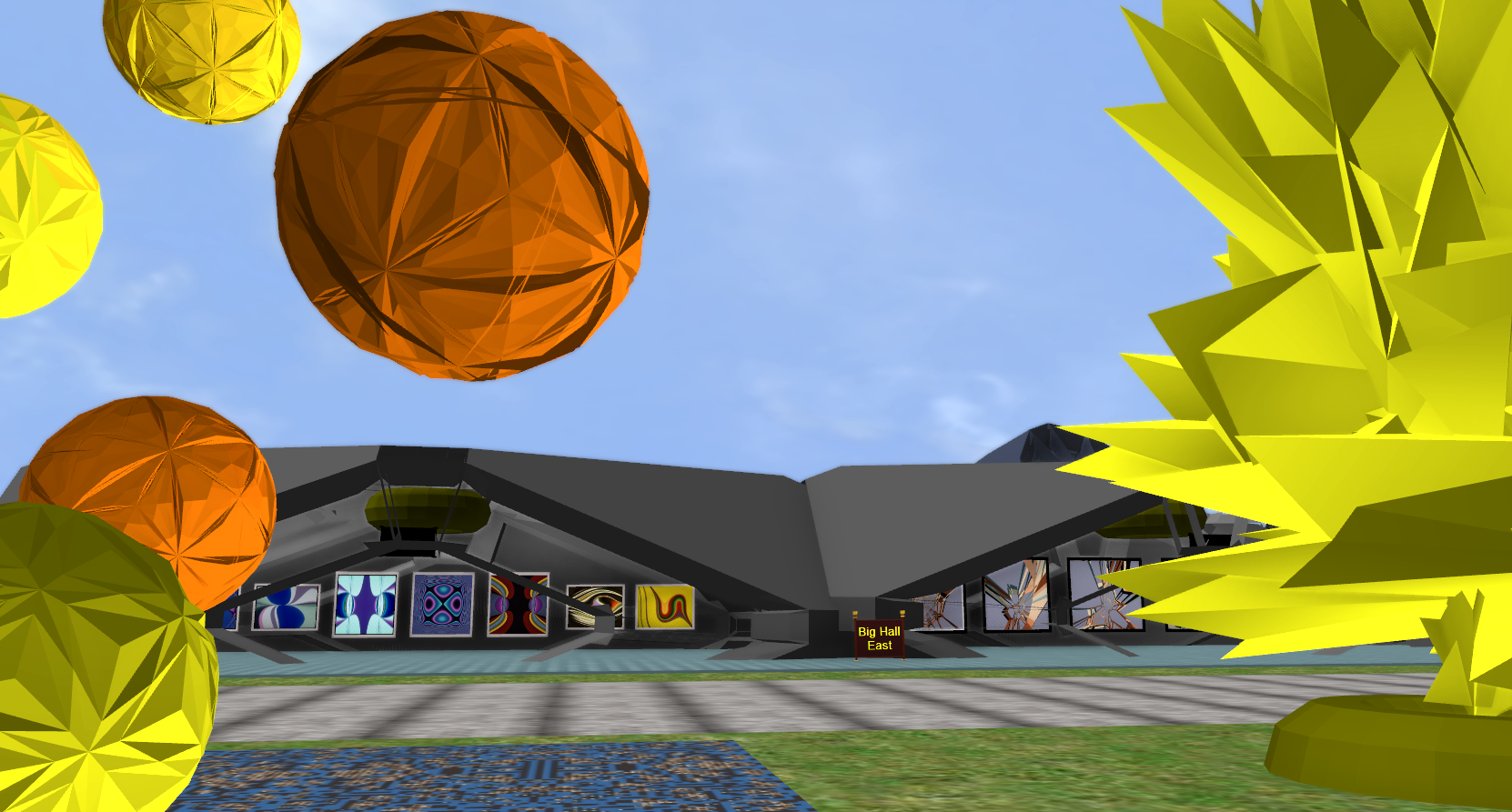

All Franke’s numerous innovations (from Einstein, one of the first artworks created by digitally processing a photograph, to building a virtual gallery named Z-Galaxy inside an early version of the metaverse) were undertaken as an independent scientist and researcher. “Freedom was the big advantage”, Franke explains. “The disadvantage at the beginning was that I had to find ways to finance my life. I worked as a publicist and writer. I wrote science fiction books [Die Zeit has called him “the most prominent German writing Science Fiction author”]. I gave lectures about my art theory. I worked as a consultant.”

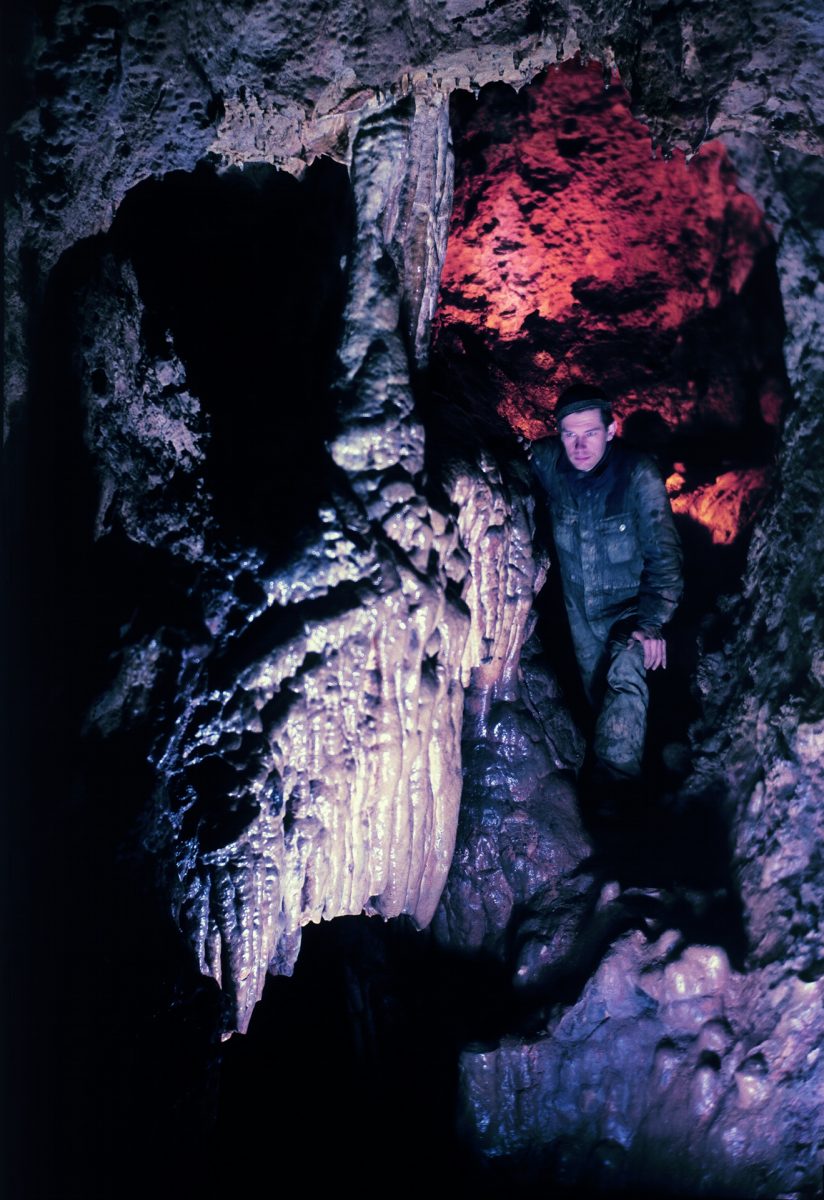

He even found time for cave exploration, resulting in pioneering work on paleoclimatology. How did he manage so many disparate careers? “Susanne says that I was very fast… and a workaholic.” And the thread that links them? “My curiosity about new findings, the exploration of new territories and emerging technologies.”

“After fifty years, my work is old enough to look at from an art historical perspective. I guess I was too early”

Why does Franke think the time is right, now, for his art to be recognised? “After fifty years, my work is old enough to look at from an art historical perspective,” he answers. “I guess I was too early. Of course it bothered me that my thoughts, ideas and art were rejected, but not in a way that made me give up. I was certain that what I had discovered was correct. Mathematics cannot be deceived.”

- Left: Herbert W. Franke’s series “Oszillogramme” (“Oscillograms”), Generative Photography calculated with a self-built analog computer/output device oscilloscope, photographed by a moving camera in front of the oscilloscope with open aperture, 1954-58. Right: Herbert W. Franke after a cave exploration, White Desert area, Aegyptian Sahara, 2007. Copyright Archive Art Meets Science

Speaking on a panel at the opening of Visionary, Irish conceptual artist and cryptoart pioneer Kevin Abosch emphasised a different aspect of Franke’s oeuvre. “It’s taken a long time to understand the emotional value of his work,” he said, before addressing Franke directly with, “It’s almost impossible to create something using generative tools and it to not look like something you’ve done, Herbert! He’s done it all.”

The long wait for recognition has done little to dim Franke’s sense of gratitude… or humour. One week into his time on Twitter he posted; “I am overwhelmed by your praise for my early work. Too bad I’m no longer 80. Charged with so much energy from your positive response, I would have started something completely new…”

Steve Taylor writes about cities, music and urban culture. He recently started a PhD on underground music scenes and the future city

Visionary is at Francisco Carolinum Linz until 12 June