Joel Shapiro is well-known for his prolific career as creator of idiosyncratic gestures and curiously proportioned figures. He is currently inaugurating the brand new Sculpture Garden at Kasmin Gallery (which opens today), located atop its new Studio MDA-designed gallery space in the heart of New York’s Chelsea district. A pioneer of American sculpture, three of Shapiro’s large-scale bronze and aluminum pieces will reside in the garden until the end of December. They show figures caught in the act of falling or running, invigorating their surroundings and triggering dialogues with their audiences around figuration and motion. Public engagement is crucial for the exhibition, especially considering the rooftop is adjacent to the tremendously busy High Line, the city’s elevated public park which also maintains an ambitious public art programme.

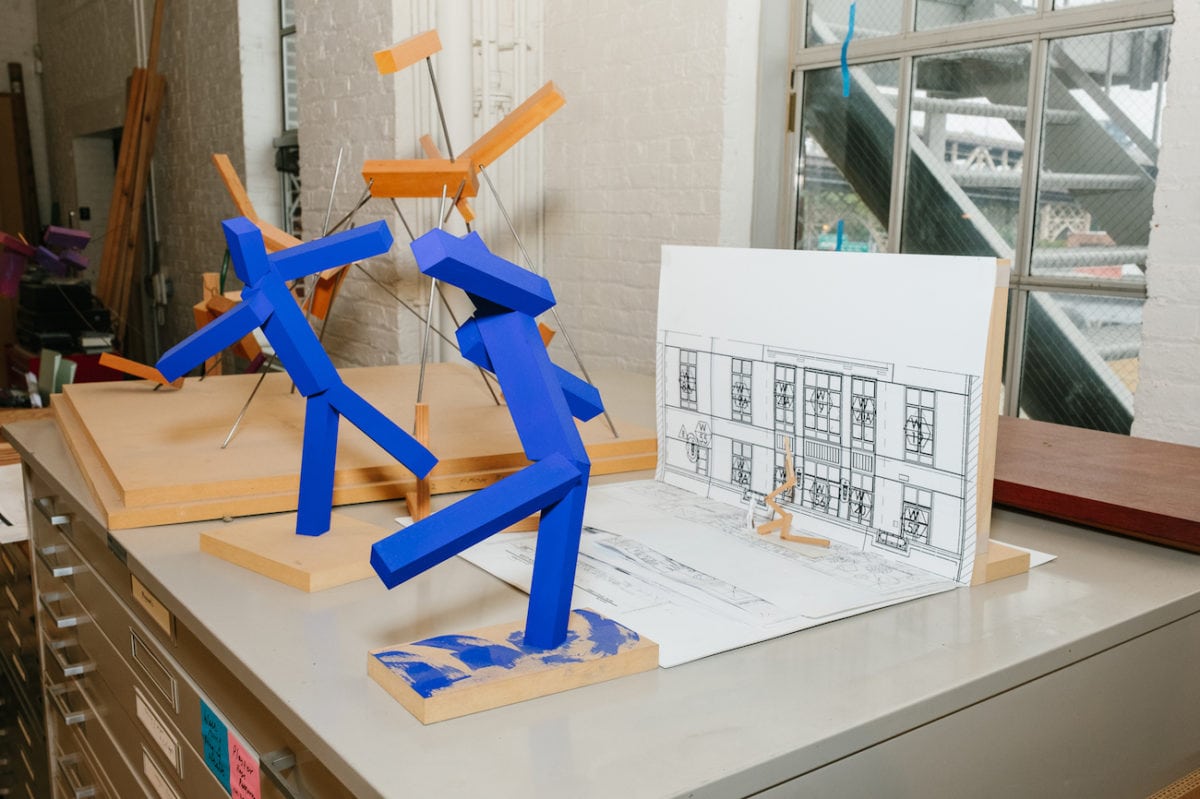

Last month the seventy-seven-year-old Shapiro opened the doors of his Long Island City studio, which overlooks the East River, amidst preparations for his public unveiling.

You’ve been experimenting with the glue gun and pin gun for your models, working up from initial stages of production to finalization at the foundry. Can you tell me a little about your process as you work towards your final pieces?

I tend to join things rapidly. The works in this show are not colossal; they don’t intimidate the audience. A good example for this transition is on the surface. When I make small models with wood and glue, the saw marks from the wood after being cut with a sawmill pass onto the surface. A six-foot circular saw trims the wood and breaks up the surface. This texture refers to the hand and the wood, rather than an industrial finish. Small marks on the original model become larger and come into the surface on the final sculpture.

“My work is about surrounding its space without being imposing”

Rooftops have a unique quality for being somewhere between public and private. They’re not as private as a gallery or residence, but they are not completely public either. Did you approach this exhibition as a public art project or a gallery exhibition?

There is one aluminum piece I had decided to paint, but I later realized it’d be too aggressive for its site. I am conscious about not putting anything edgy up there. I think the works will look interesting next to the new Zaha Hadid building. My work is transparent enough not to block the view, especially considering the work parallels the Hudson River. The sense of containment in sculpture is interesting, but not always at a public venue. My work is about surrounding its space without being imposing. The rooftop is only at a six-foot gap from the High Line, so there is that merger of public and private, or intentional and accidental. The risk that people might like or resent it is always there; any art in public raises issues about whether the work is rewarding for its public.

When you start with a small model, are you immediately conscious about transforming it to a larger scale or is the final scale decided as the work progresses?

What an artist will do, to some extent, depends on what they’ve so far done and whether that has been satisfying. In this exhibition I am showing works I’ve kept at my studio for a while. The rooftop has three sections to exhibit art and they are architecturally pretty flexible. Two of the pieces in the show are actually commissions. The bronze has that texture from the sawmill, so the surface is engaging. I am interested in setting up aspects of a sculpture, so I tend to determine how the viewer looks at the work. This is about being directive for the viewer, about where to look at the work from without blocking the space.

Do you believe sculptors should make the audience take a full circle around their work?

In this case, the tour will be a 180 [laughs], due to the roof’s structure. The viewer can only see the works from the High Line or from the buildings around the rooftop.

If minimalism is associated with stillness and demureness, your sculptures challenge that notion with a sense of dynamism and mobility. They give a sense that they could walk away at any second.

I’ve never felt it’s possible to invent a single form or shape. My work references specific figurative forms, and this doesn’t bother me at all. While minimalism is against reference, I’ve always insisted on being referential, although most of my work is much more abstract than the sculptures I am showing on the roof. Art historian Richard Shiff

once pointed out the elemental aspect to my work, which is something people can understand and relate to. For example, you might see a kid imitating the piece because he can engage with it.

“While minimalism is against reference, I’ve always insisted on being referential”

In Roberta Smith’s catalogue essay for your eponymous exhibition at the Whitney in 1982 she says, “Shapiro’s main strength turned out to be a kind of indecisiveness, an uncanny ability to make something good out of not being sure of himself.” How has this indecisiveness changed since then?

JS: I don’t think it has changed; I doubt everything I do, like most artists—otherwise it’d be presumptuous. This is a process of questioning, which doesn’t mean artists hesitate to show what they’ve done. Malcolm Morley at Max’s Kansas City once said at to me, “Artists develop in public,” which is one of the most profound things I’ve heard from another artist. I can keep looking at my sculpture and come up with many ideas about its colour or whether it looks too stiff. There are moments of rupture telling me I’ve done something that I hadn’t anticipated. As I get to know it, the rupture begins to dwindle with the realization of more to do. Therefore, there is no retirement for artists. Going back to your question, I guess I still have that indecisiveness. By questioning what I’ve done within the world of sculpture, I don’t have to assume full responsibility. Doubt and failure are parts of the process.

- Work being installed: Joel Shapiro, Untitled, 2015-16. Courtesy of Kasmin