Welcome back to Critic About Town, a column where Zarina Muhammad writes about exhibitions in London and tries to make sense of that against the wider mood of the culture (whatever that is).

I’ve been on silent mode, afk and on hiatus when it comes to this particular column. Don’t for one second assume that I was on holiday. I was NOT. I am the only person in the entire world who was working and in London for the whole summer. I am bitter and resentful about it. Very very spiteful. Just me, all alone in London, concrete grey boiling city. Just me and the birds, me and the scorched grass, me and the wistful dream (of leisure, fun, pleasure, not-working). I feel hard done by, but art was there to keep me company. If you were on holiday, I was on guard dog duty and I’m going to tell you what you missed.

Rewind several months to the end of June, the Royal Academy’s degree show. I walked round in the middle of a heatwave, sticky, stiff and dazed. Out of all the London degree shows, this one is immediately grand and illustrious. It’s in the lofty halls of the Royal Academy, just off Piccadilly — but also there are only a literal handful of students in each year, they get the luxury of all that space at the back of the building to themselves. Entire rooms to spread out, relax into, treat it all like a solo exhibition — immediately lovely. The first room I walked into was the Weston Studio, ‘a place of constant transit connecting two parts of the building’ — the Royal Academian front and the art school back. In this room that was also an atrium and also a foyer and a landing, Ilze Aulmane had an installation called Mood board of my garage.

The tall walls were lined with enormous images. Mostly paintings on paper or un-stretched canvas, tacked up and overlapping. Black landscape of volcanoes exploding, bloody teardrop, blue volcanos, purple mountain, glowing mountain, mountain split wide open against the roaring sea, POV phone cam pics of the artist on a sun bed under the fluoro UV lights (with the little metallic paper goggles they give you at the shop), knees, feet, nipples, tinsel, red tarpaulins, crashed office chairs; strips of image spilling over each other. On one short wall, under a window and clear from interruption: a large square painting of two cherry red Ferraris crashing into each other as they speed round a corner. The paper tacked underneath was another sun-bed interior, and it swirled around the car crash scene like a vortex.

The room was wide and shallow, on one long end there was a door and on the other, an open stairwell. Tape tracks had been drawn across the width and as I looked at the images lining the wall, the artist started parading up and down the taped track. Holding a long pompom with black plastic tinsel, swishing back and forth in the air. The tinsel was matte black, thin and plasticky— exactly the same soft material as bin bags (the nice kind). The pompom never stopped still, it made lines in the air, constant movement. I was transfixed because it was elegant, graceful, like ballet, so soothing and pleasing, a balm for my eyes and my brain to watch this soft swishing plastic motion, hear the soft shushing sound of the tinsel strands rustling against each other. Not looking at the artist at all, and the artist not looking at us in the audience, both just looking at the moving tinsel, swishing and rushing like a puppet. Up and down the track a few times, then changing pompom. This one a long stick, curved like a shepherd’s staff with short baby pink tinsel. The artist waved it round in circles so the curved hook swung round like the drooping hands of a clock. Another: this one with two sticks, the tinsel all silver and long and green tissue paper strung up between the sticks. The artist swooshed these like a net, like a banner, they caught in the air and sparkled as they dragged. The artist moved slowly to account for the pull and the weight. It spread out into the air like a cloud, like smoke, like a body. Another long stick, this one completely straight with long metallic silver tinsel that wriggled and writhed in the air, unable to move straight. It made a crisp crinkling sound, it felt like something parallel to a carnival and rainwater.

The performance itself lasted 10 minutes, it was like a wordless balm for my eyes. I was only thinking about the movement, the shape, the sound — it is so weird and rare to find those three things outside of a body. But the performance was completely non-bodily, pure movement, almost completely abstracted from figuration. Each pompom was different, in shape and movement and character. Some were celebratory, some were flags, some were like swooping ghosts. I still don’t quite know what to make of the sun bed and car crash and mountain scenes tacked to the wall. If I’d wandered through at any other time, my experience of this room would’ve been completely different. I wandered through the rest of the degree show feeling like I just witnessed something bizarre and special out the corner of my eye, thinking about something bodiless and wordless, beautiful and abstract.

The same thing came back a couple of weeks ago. I’d been over at Chelsea (the art school, not the Royal Borough Of) for a job interview, and after the ordeal of standardised answers, I dragged myself over the road to the Tate Britain and Alvaro Barrington’s monumental commission: GRACE. It is genuinely monumental, everything in the Duveen Galleries kind of has to be, because the neoclassical enormity just swallows up human scale. In the very middle, the gallery splits open into a round space surrounded by columns and lit by enormous skylights. There’s a scene set like an ode to carnival: a towering larger than life sculpture of a woman dancing, she is silver and draped in fabric, surrounded by a ring of steel drums and corrugated sheet metal, she is in movement and godlike. Around her, scaffolding frames with canvas walls to display paintings of carnival scenes. The canvas is stretched with zip ties pulling the images taut.

One of them is what I’m looking for: across two panels, a pink hazy expanse covered in busy confetti. It has exploded and it’s midway, shimmering through the air. There’s one figure in the bottom right, small with arms raised in movement. But I am thinking about that static confetti, stuck in transit because a painting freezes a moment. I am thinking about how that confetti would move if we unpaused it. It is the entire subject of those two panels, it is the foreground and object of attention. It’s spread across the surface, even plane, tone on tone, pink blue yellow and green. It is stuck on joy, pure abstract joy — what else could confetti be? Bodiless, celebratory.

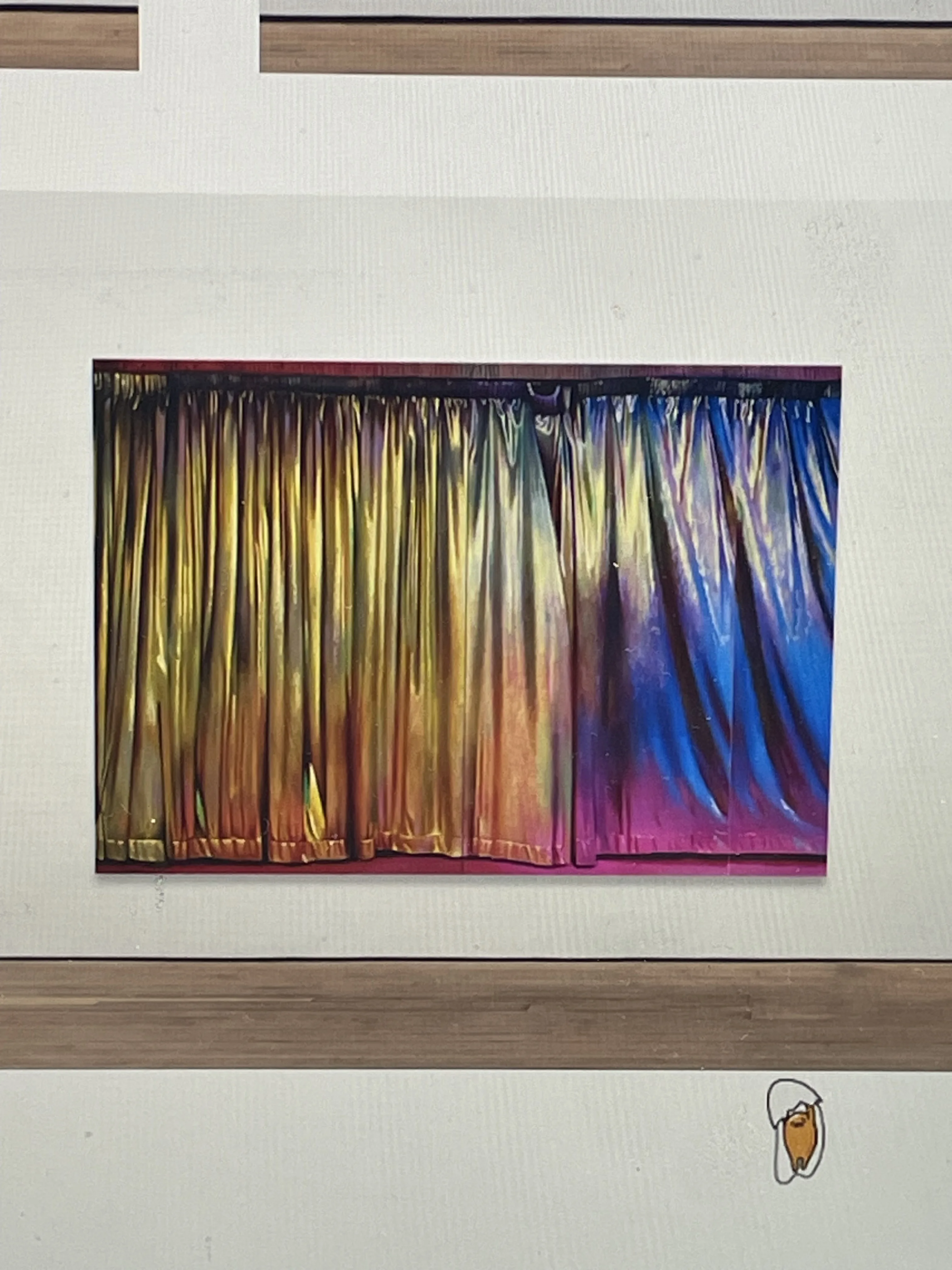

I feel like there’s something in common between these works, these moments. Something in common — it’s whatever gets left after summer fucks off. Or, no — it’s something glossy and bodiless, peripheral vision, residual. A couple years ago I was walking past Chinatown on Chinese New Year. I turned my head and out the corner of my eye I saw straight down a side road: the lads were manoeuvring an enormous red dragon on wires and stilts. The dragon was snapping up at a second floor window, trying to catch a plushie bok choy being dangled out on a fishing line. I turned my head away, didn’t stop, when I turned back the side road was gone — replaced by more shops, bus stops, crowds. It’s also like Louise Giovanelli’s shimmering curtains, the way she is able to paint fabric like metal and water, elemental, being abstracted with slightness. I think about her paintings all the time: of green and glass, bubbles rising, lips refracted by liquid, or gloss, light shining on the backs of heads, open mouths and smooth skin overlaid on more skinskinskin. Shimmering, sparkling, reflective, metal, sheen, that is all a varying kind of bodiless abstraction, pure and joyful and residual. It’s out there in the work on show, I can’t un-see it.

Words by Zarina Muhammad