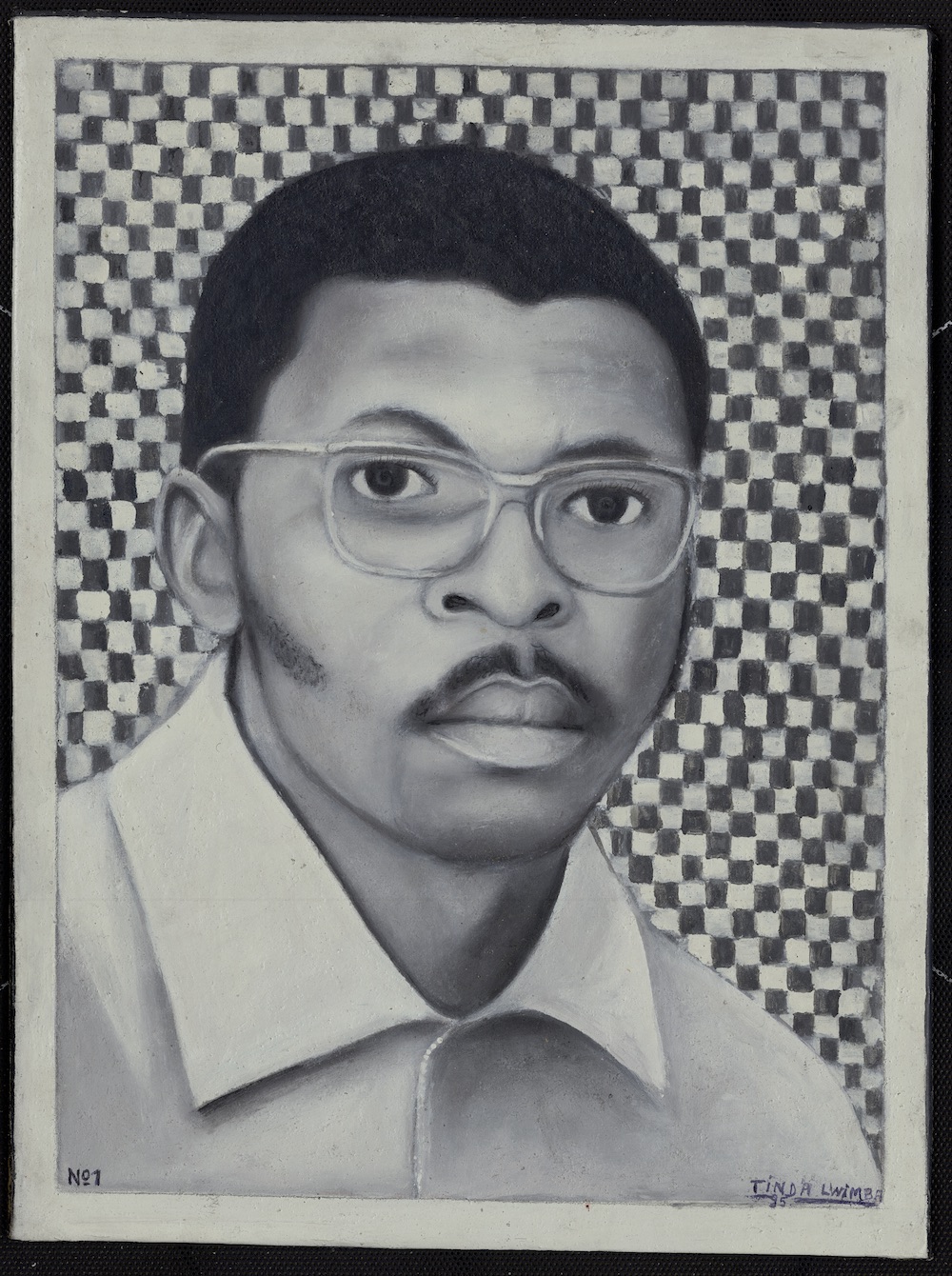

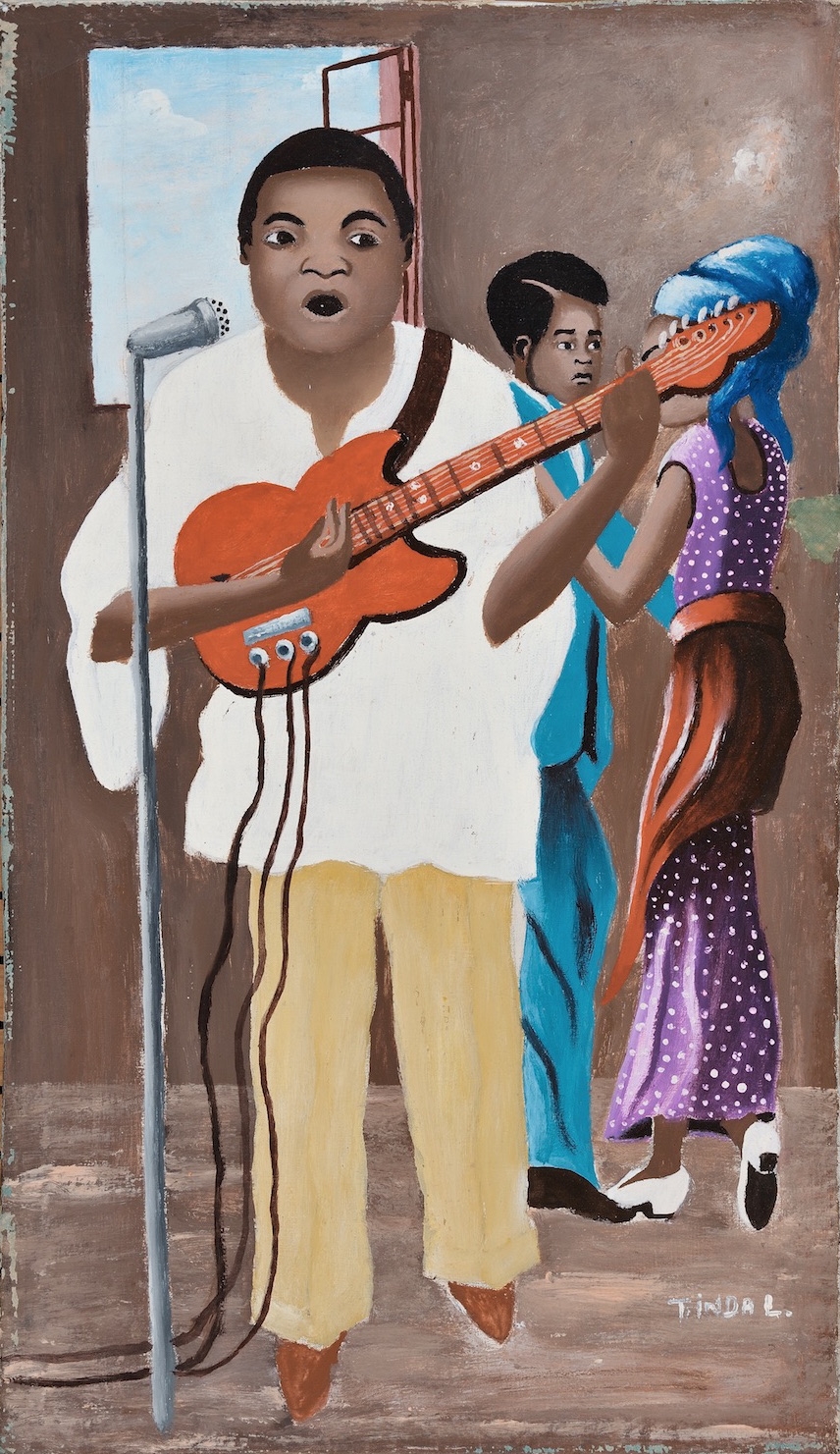

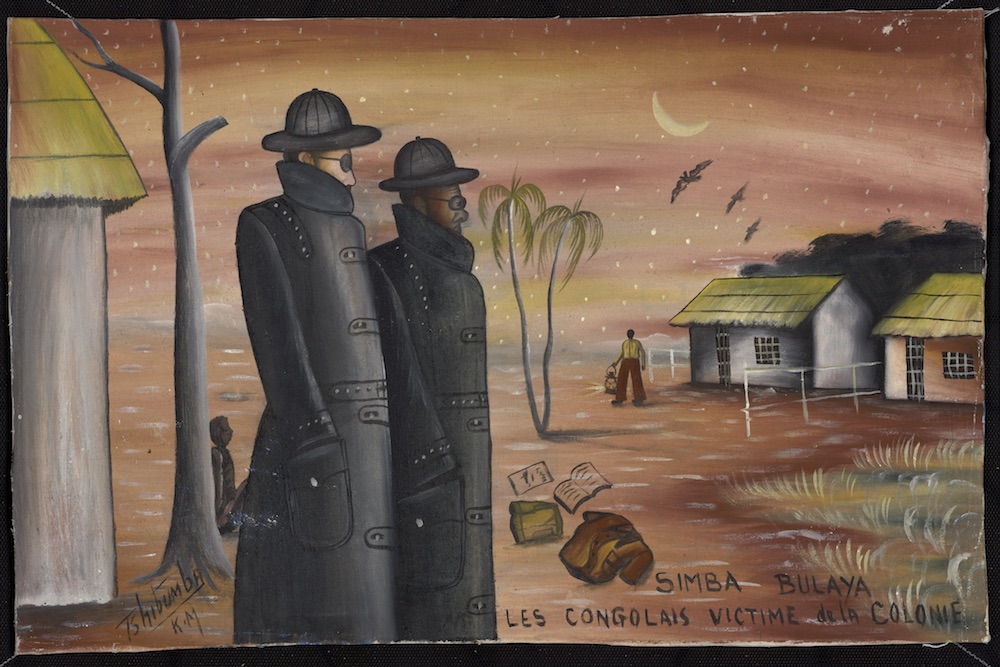

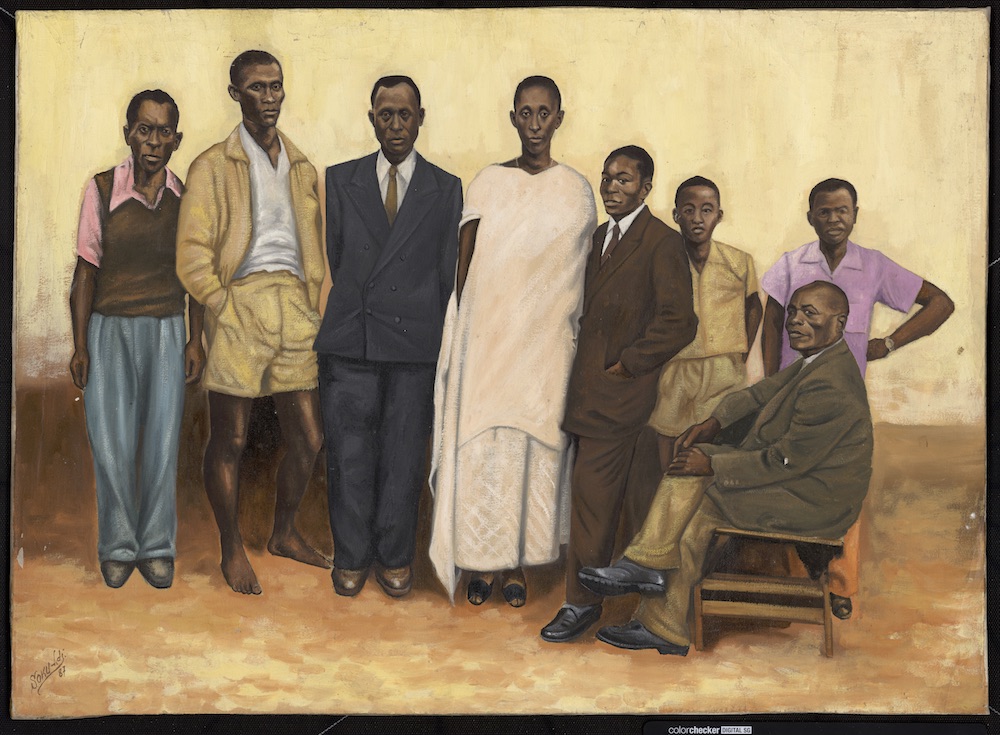

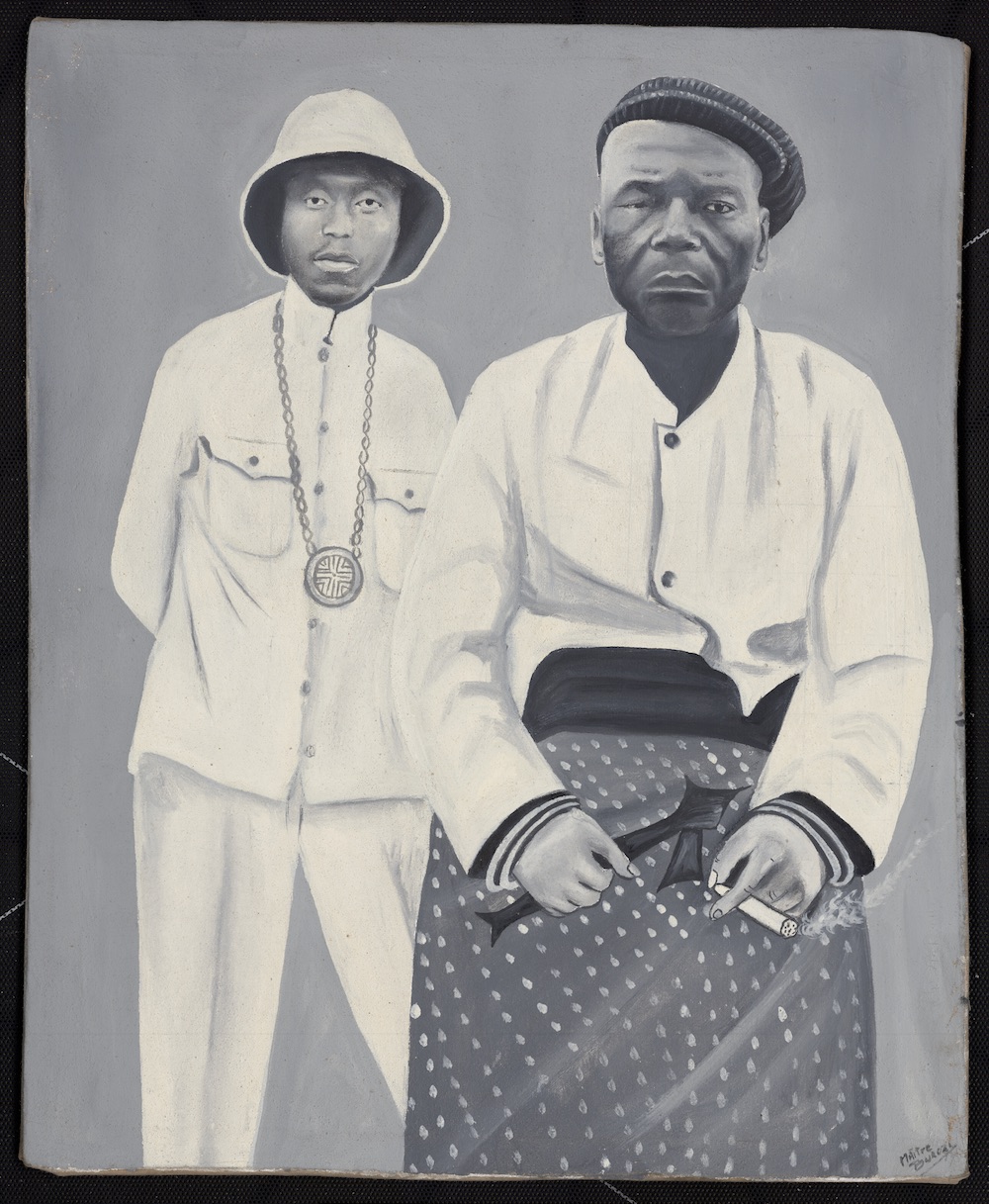

The ‘popular painting’–a genre of African art for the masses inspired by everyday life–that has developed in the post-independence Democratic Republic of Congo has a distinctive style, yet the attractive bright colours of these works at first belie their political power.

The paintings on view as part of Congo Art Works: Popular Paintings at Bozar in Brussels trace the trajectory of this singular movement of Congolese painting from 1968 (eight years after independence) all the way to 2012, a turbulent time in the DRC that has been punctuated by crisis and conflict that continues to destabilise life for many across the country.

The responses of local artists to the moments that have marked their recent history are far more varied than we might be conditioned to think in the west. Until the 1990s, these paintings would have been produced primarily for a Congolese audience–sometimes as commissions–making them a unique collective collaboration that merges memories and perspectives.

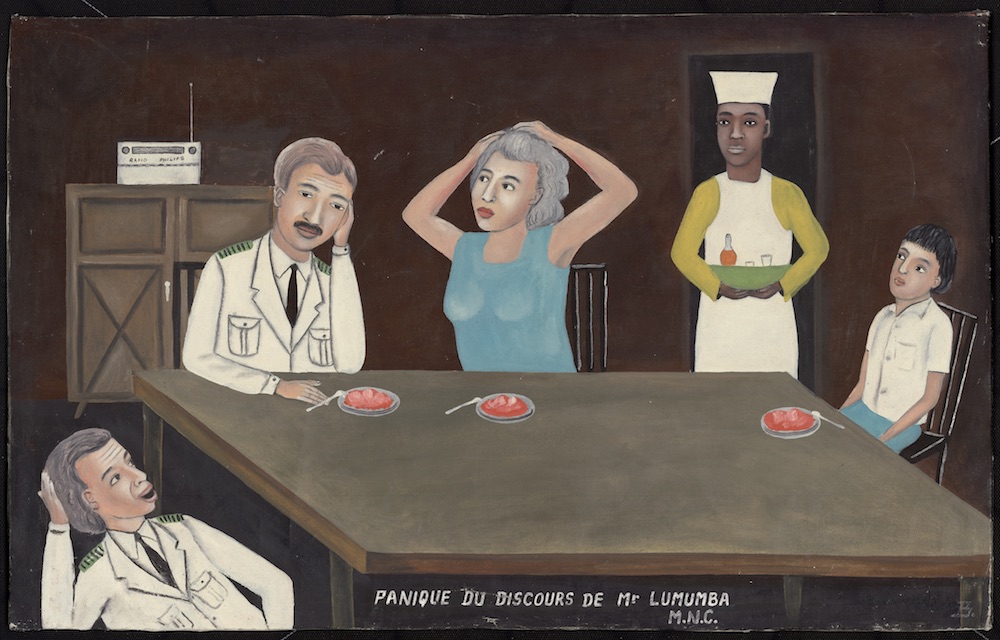

In Burozi Lubumbashi’s Panic at the speech of MR. Lumamba N.N.C for example, a white–presumably European–family, the men dressed in military uniform, sit around the dinner table listening aghast to the radio, playing, as the title suggests, the historic address given by Patrice Lumumba–the first democratically elected leader of the Congo–in 1960, a searing take down of the colonial rule. The black servant, holding a tray, stares proudly into the middle distance.

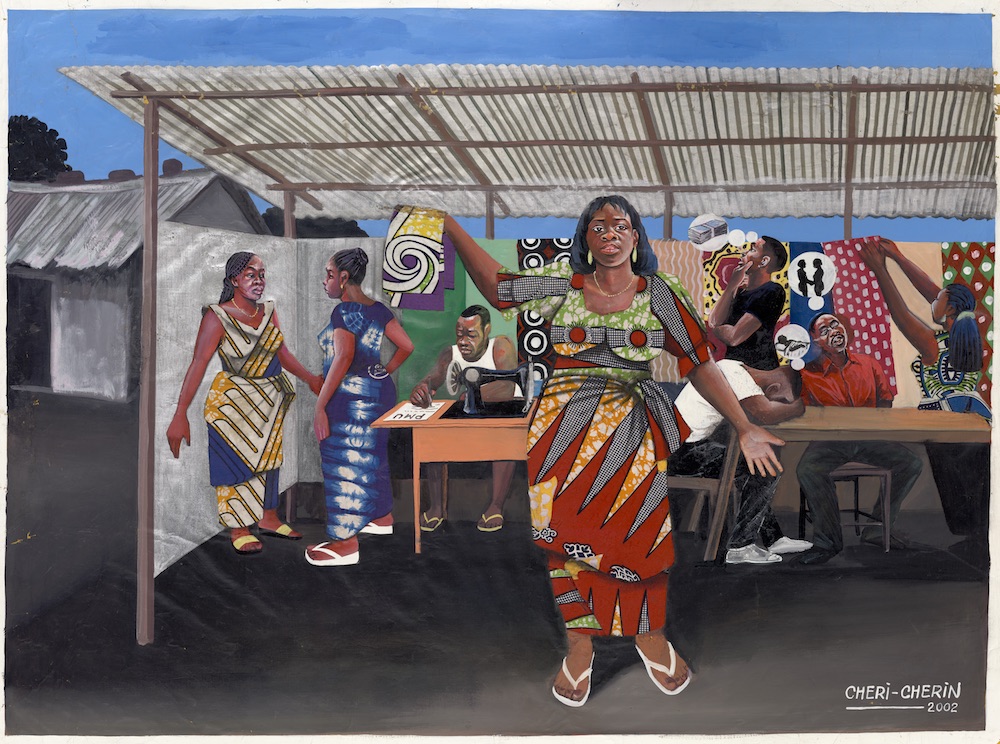

Other works express the normality–even banality–of everyday life, going on, as it does, even in the toughest of times. There are numerous pieces from the late 1990s and early 2000s, during the devastating Civil War, such as Cheri Cherin’s The Cloth Seller which shows a busy textile kiosk at work.

Produced by the Royal Museum for Central Africa and curated by Congolese photographer Sammy Baloji and anthropologist Bambi Ceuppens Congo Art Works gives contrasting images of the Congo as seen by the Congolese, reflecting Belgian colonialism, exile, and war, but also music, dancing and shopping. One of the major concerns of the curators, though, with the more recent acquisition of popular paintings abroad, is to question the role of the European museum in colonialism and neocolonialism–implicating the same institutes in which these paintings now hang. Nowhere is this more glaring than in Cheri Samba’s seminal Réorganisation, (2002), a tug of war between white and black, coloniser and colonised, European and Congolese, at the entrance of The Royal Museum for Central Africa.

‘Congo Art Works: Popular Painting’ runs until 22 January 2017 at Bozar, Brussels.

Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, Simba Bulawa, les congolais victimes de la colonie, Lubumbashi 1973 © Royal Museum for Central Africa

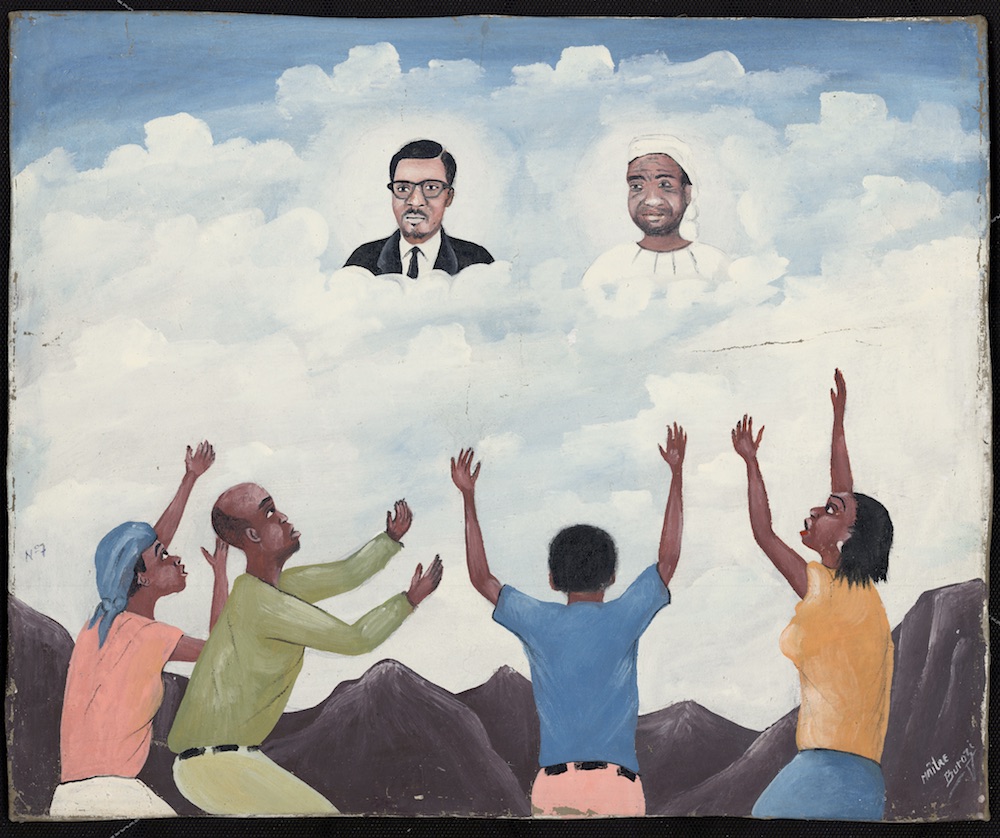

Discours de Lumumba Auprès des Congolais Tshibumba (Burozi), Lubumbashi, 1998 © Royal Museum for Central Africa