Through a multi-year initiative and an exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, the artist offers practical and abstract solutions to salvage the legacy of a community built by freed Black people directly following the Civil War.

Theaster Gates: The Gift and the Renege at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH) engages with the material history of Freedmen’s Town in Fourth Ward, a historic community in downtown Houston built by newly freed Black people after the Civil War. Once described as the “crown jewel of the Emancipation Trail,” Freedmen’s Town is one of seven sites recognised by the UNESCO Routes of Enslaved Peoples Project. But it has faced decades of neglect and encroachment by urban development. The hand-made bricks that once lined the streets of Freedmen’s Town—and were laid by its original residents and not the city of Houston—are now partially destroyed, and how to preserve the existing bricks and surrounding infrastructure remains a point of contention for the community and the city.

Expanding on the work Gates has done with the Rebuild Foundation, a nonprofit he launched in 2010 to repurpose and preserve historically Black spaces in Chicago, the exhibition is part of a larger $1m initiative called Rebirth in Action: Telling the Story of Freedom, which was launched in collaboration with the CAMH, the Houston Freedmen’s Town Conservancy and the City of Houston, with funding from the Mellon Foundation and the NEA Our Town Grant. Like Gates’ previous projects, the show aims to prompt dialogue around Black displacement and resistance but additionally provide practical solutions like infrastructure planning in close collaboration with the longtime residents of the neighbourhood.

The exhibition was realised with Ryan N. Dennis, the MCAH’s senior curator and director of public initiatives, and the museum’s director, Hesse McGraw, to explore preservation efforts in Freedmen’s Town. On the heels of a severe storm in Houston (since dubbed the “2024 Houston derecho,” it was a timely example of the ongoing threats to the infrastructure of Freedmen’s Town), Gates sat down with Elephant Magazine at the CAMH offices to discuss the works in the show and his ongoing collaboration with the Freedmen’s Town community.

GA: How did you become interested in Freedmen’s Town and how did that interest lead to the exhibition?

TG: I have this long history with [CAMH director] Hesse McGraw. Once he arrived, I think CAMH was thinking about how it could be more deeply invested in the life of the city and how artists could be a part of that activity. He had been introduced to folk in Freedmen’s Town and knew that there was this dilemma around the bricks. I was doing work around brick-making and brick manufacturing. He asked if I could come give the city some advice on what to do with these bricks and we realised pretty quickly that there were some strong feelings around what was working and what was not working in terms of the relationship between the community and the city.

I found myself jumping into a hotbed of relationships and thought about how my practice could disrupt some of the ongoing politics. How could we get these bricks out of the ground and stored? Then, how do we rebuild Freedmen’s Town? I wanted to put some infrastructure on the ground and some investment in the area. Over the last three years, we’ve been slowly building a better relationship with the city and empowering folk in Freedmen’s Town.

In that sense, the exhibition has become a calling card for those who want to be aligned with the art museum and with contemporary art. Well, how about you also align with this place that we’re referencing? It’s become a pipeline of resource transfer from the creative investors in the city to a place that really needs it.

GA: After the exhibition, what will your relationship with Freedmen’s Town look like?

TG: These are friends now. The exhibition really came out of working with folks in the community. We’re building infrastructure so that Freedmen’s Town as a whole can be in a better place. There are other partnerships that have come out of this friendship, which I hope will be ongoing ones. I’ve really only been an advisor here. But because I was an outsider, I could ask questions that maybe people felt would be too inappropriate to ask because they didn’t want to ruffle feathers. Because I don’t have any stakes in the politics, I could just ask questions because I wanted Freedmen’s Town to be the best it could be. I think I’ll continue to be an advisor and—if they allow me—I would love to lend my interest in architecture and design to this place.

GA: The works in the exhibition like Retaining Wall for Revolution and Resurrection (2024)—a work using salvaged materials from a former hardware store in Freedmen’s Town—seems to reference your interest in Shintoism, or the animist approach to materials in your practice. How did those ideas play into the show?

TG: Historically, animism in the continents of Africa and Asia are rooted in nature—trees, rocks, water and certain geographies that were so unique in their nature that you would find spirit energy resting there. But it was energy that you could disrupt or destroy and, if you did that, there might be consequences to that action. As a result, you were constantly in negotiation with nature, which became a wonderful way of building an environment of reverence, where nature was more important than human need. In a non-animistic environment, if there’s a 400-year-old tree, you pull it out and cut the wood and build a road or something there. But if we’ve determined as a group that this tree is sacred and holds value, you build your road around it. Imagine transferring that belief to a snowblower, or a vacuum cleaner.

This is part of the reason I began thinking highly of Jeff Koons’ practice, for example. He understands that there’s a mystery in the everyday. With Retaining Wall for Revolution and Resurrection, using materials from the hardware store, I feel like one can come to understand the communal, community-based sacredness in those objects. Not that any one object is godly, but the choice to believe in the power of their life means that I’m going to regard them as greater than just generic inventory and throw it all out. I’m going to build a temple for them. I’m going to build space for them. I don’t feel like an environmentalist, but rather like a preservationist. That preservation has everything to do with how one preserves because one believes in the materials.

GA: What was the thinking behind some of the other works, like the yellow welded steel panel, Bright Sunny Day (2024)?

TG: It’s a material called rubber torch down, a contemporary roofing material that isn’t widely used anymore. It’s rubber in the back and has a layer of tar on it. You torch the back to activate the tar. Then, when you assemble them one on top of the other while it’s hot, you press it down and the tar squeezes out. It’s that black line that guarantees you that it is well-seamed. I’ve taken this tradition that I grew up doing with my dad and I’m now using an industrial enamel paint, or a reflective roofing paint material that’s basically like liquid alumina. It reflects and deflects light. I’m attempting to make abstract paintings with this material that started as a kind of homage to the work that my dad and I did together.

Works like Bright Sunny Day are about self-determinism. From poor, subjugated people, great things can happen. Had I been born in a different circumstance, where I didn’t have time with my dad to make a roof, I wouldn’t have been able to get to that work. When I was doing it, I was pissed. It was hot and tiring and smelly. It was a certain type of Black labour and I didn’t have an option. I had to help my dad because he couldn’t afford another man on the job. But I knew I had to do something that could transcend roofing. That’s called art. That work is also an anthem. Yes, sometimes our everyday things are a little janky but we’re going to do the best we can with them. There’s pride and dignity in Freedmen’s Town, for example, and we won’t let anything change our outlook on the place.

GA: What are some parallels you have found between your work in Houston versus Chicago?

TG: I feel like there’s something special in Freedmen’s Town. There’s something special in Houston. It’s a cocktail of self-determinism mixed with the truth of tough times and mixed with laughter and joy. I feel like if there was anything my life could give to the lives of folk at Freedmen’s Town, it would be to enjoy this moment as we build and as we climb. Let’s enjoy every rung of discontent and not be dispossessed because there’s some external force that is always trying to make us dispossessed. Let’s move forward. That’s very different from some of my colleagues—pessimists who think the world is fucked up and it ain’t getting better. If I didn’t have this hope, I wouldn’t have this show.

GA: How do you believe that the exhibition can contribute to the work being done in Freedmen’s Town?

TG: I hope that the art community who may not be invested in Freedman’s Town—but may be invested in me—might become more invested because they think the show is interesting. I can’t change the social climate of Houston. I won’t even try. But through delivering an exhibition, people become curious about a place and feel like they want to contribute more to that place.

I often wonder, if an academic was trying to put a finger on what they thought my practice is, would they look at the work and call it a wonderful example of colour field painting and great abstraction? Or a social practice? Or would they think that Theaster is only making those works to sell so that he can make money to give to Freedmen’s Town? Is he some kind of weird art-making, game-changing chameleon, and we don’t exactly know if he’s investing in these objects that he’s making? What’s at the root of the practice?

The answer is that I’m deeply invested in abstraction and I’m deeply invested in the community. All of those things come together. This is my problem with a certain kind of tree-hugging artistic practice. You shouldn’t have to divorce aesthetics and an entire artistic milieu in order to be true to a certain emotional, spiritual logic. I feel like I can’t only be relational or environmental. I also have to be historical and aesthetic and I feel like the work here does that. It’s a lot more distilled than my work can sometimes be.

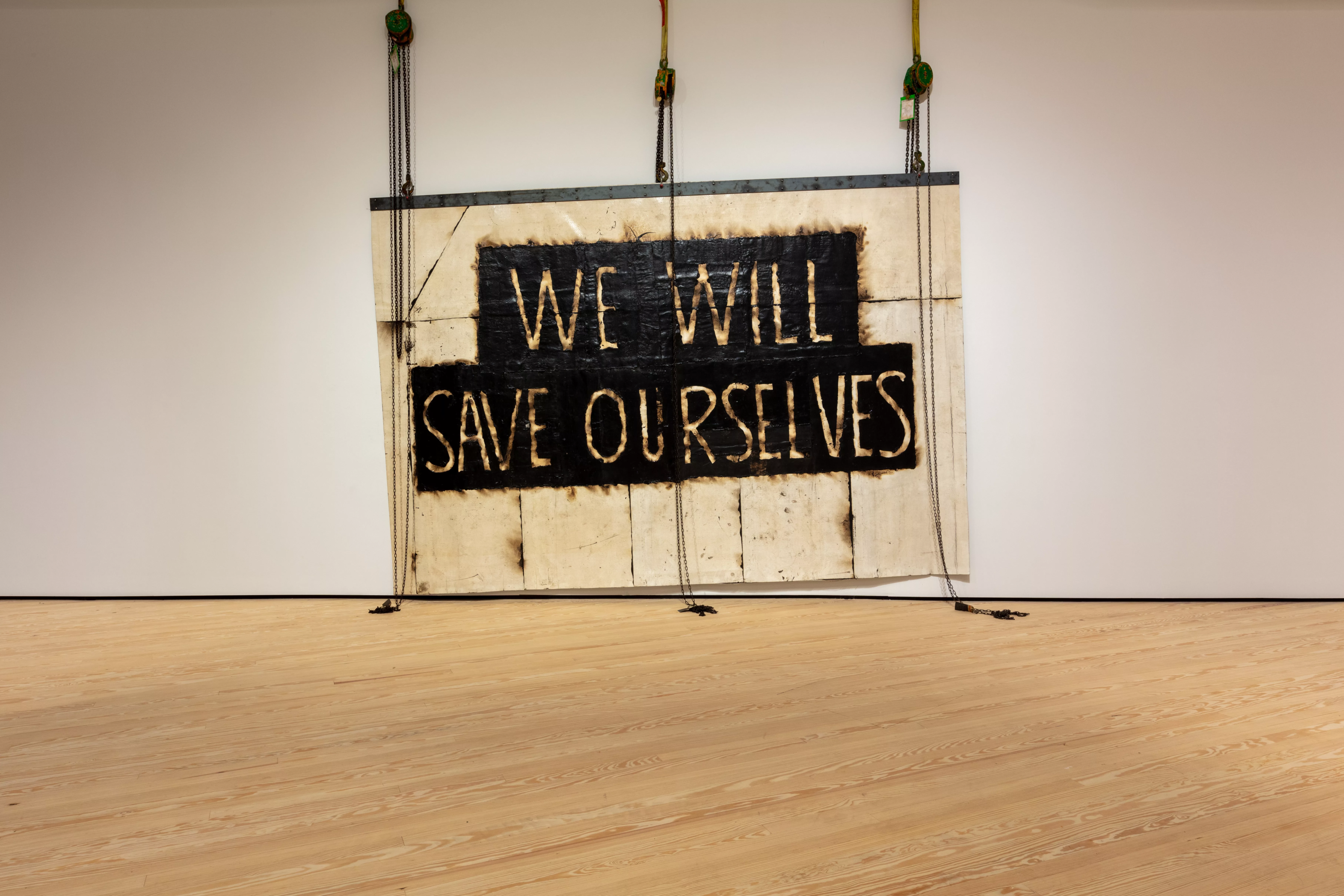

In the end, I thought, with so much art being made by so many people, what can I make that feels sincere for Freedmen’s Town? I really believe Freedmen’s Town has everything it needs to save itself. We will save ourselves. And I’m just going to keep speaking that into the lives of the people that I meet.

Theaster Gates: The Gift and the Renege, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Texas, on view 17 May-20 October 2024.

Words by Gabriella Angeleti