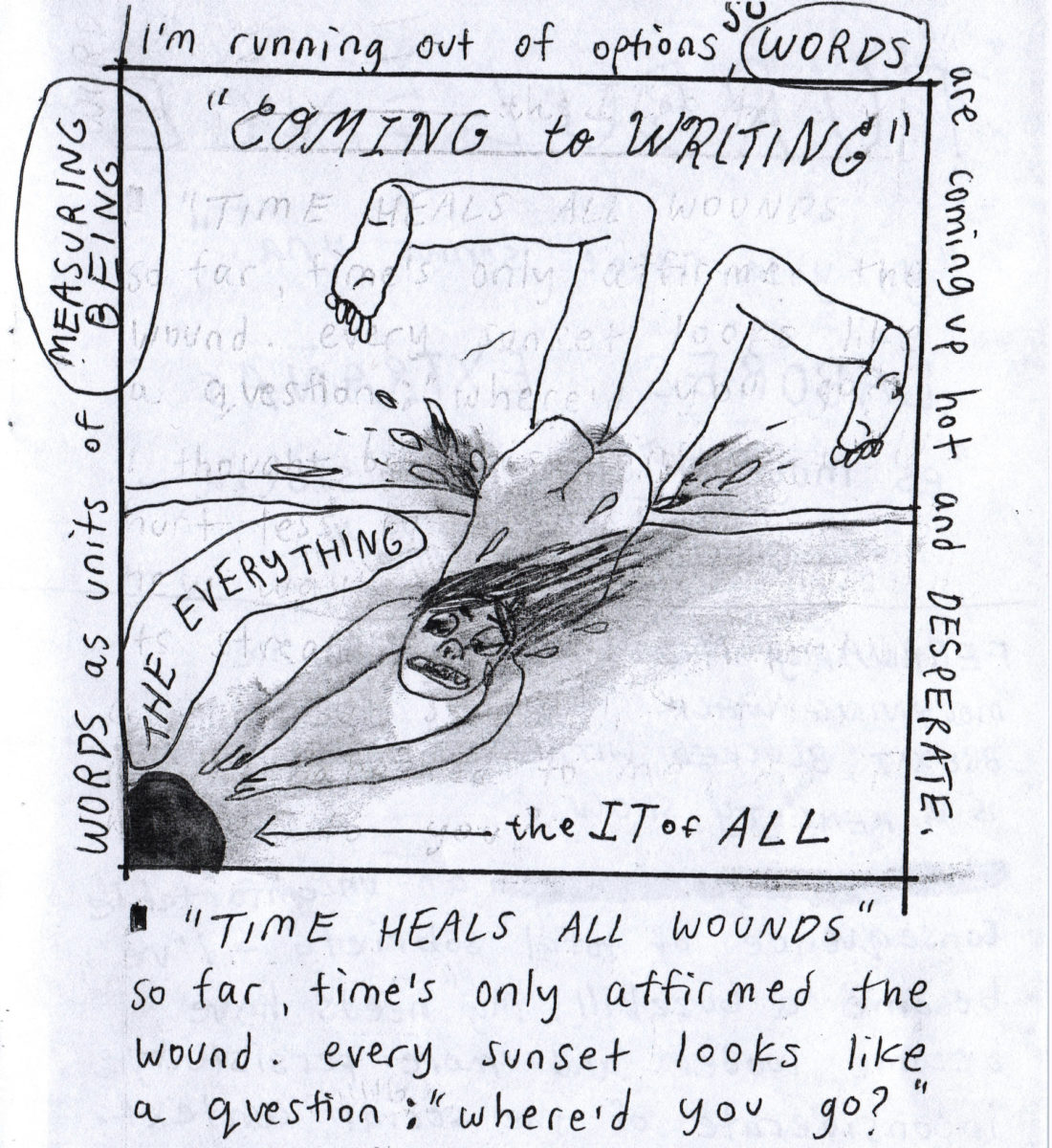

I first found Carolina Hicks and her work on a blog a few years ago in high school. My soft, sad brain lit up right away. I was immediately taken with her drawings, enticed by both the seemingly effortless, black-lined simplicity and the heaviness of what she discussed. Her work was like watching a cartoon character bleed out a dreadful rainbow. How could the approachable, whimsical nature of her work mingle, and even depend on, that dark, ill underbelly? I am still unsure of the answer.

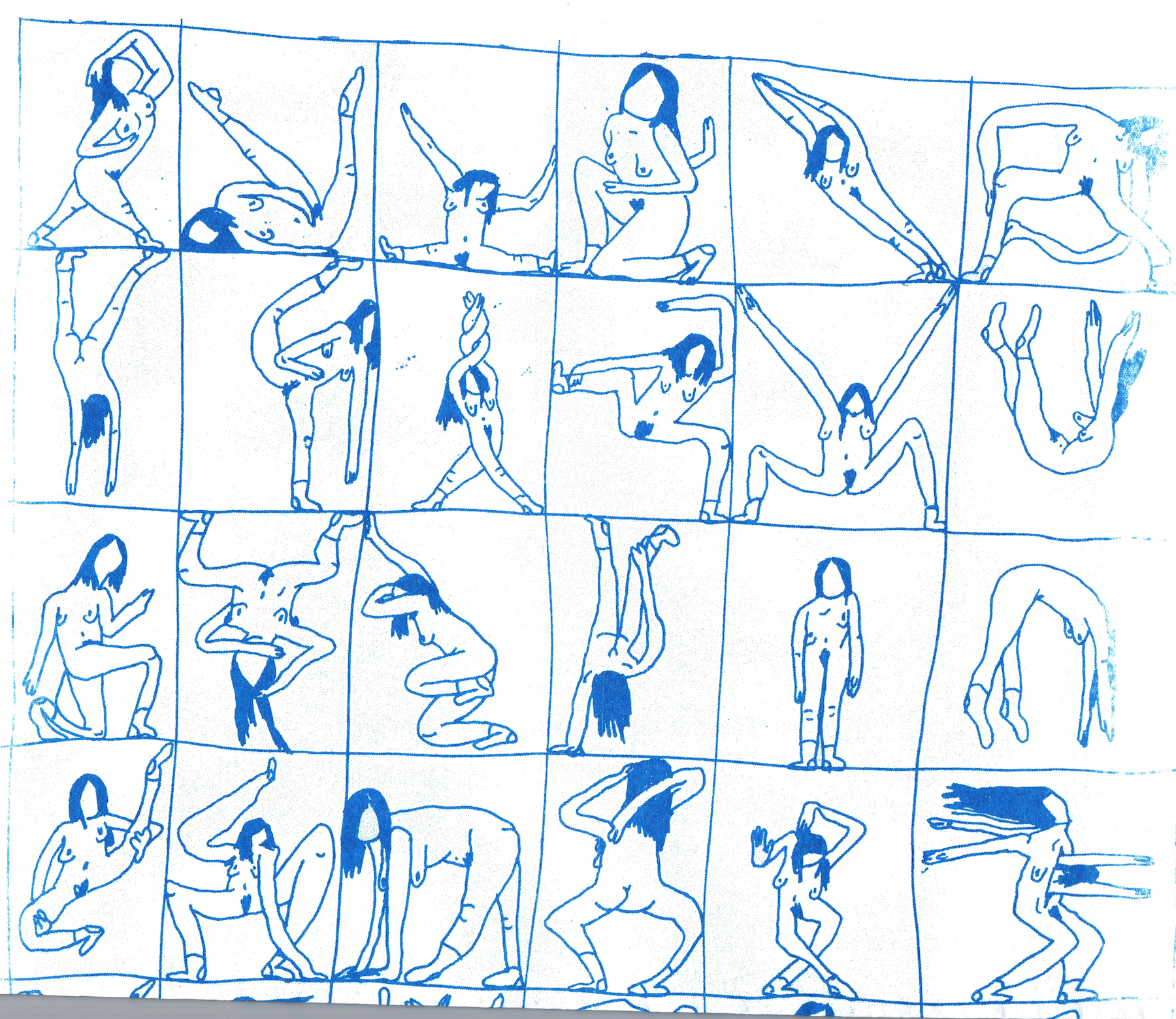

Hicks finds it difficult to claim one succinct identity, to say definitively who she is: “I’m always reconsidering who I actually am and who I want to be; it feels like I’m always mid-transit, moulting, and consistently meeting myself anew,” she tells me. Identity aside, Hicks has described herself as an interdisciplinary artist, which reflects the fact that her choice of medium is boundless and continuously expanding: she offers us writings, drawings, sculptures, comics, videos and music. Her work has been shown in numerous solo and group exhibitions. She has participated in exhibitions in the US at The Box in LA, as well as the Wignall Museum of Contemporary Art and Torrance Art Museum in California, and at the Nationalmuseum in Berlin, among others.

“ buy furosemide online furosemide online no prescription buy https://magview.com/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2019/04/zestril.html online https://magview.com/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2019/04/zestril.html no prescription pharmacy I’m always mid-transit, moulting, and consistently meeting myself anew”

When asked about her process, Hicks says: “I’m constantly digging at all these different holes but never going deep enough into one. But under the surface, hidden water connects and flows between all of these holes.” She might describe her work, she adds, as a “very earnest conspiracy theorist”, something that ties into her grander desire to prove that “everything has to do with everything; everything is densely interconnected”. All of her disparate parts are an effort to ultimately bring everything all back together; to prove this theory of ingrained, helpless connectivity.

A second-generation Colombian born in 1991 in Los Angeles and raised in the city, Hicks has a degree in anthropology and an MFA in Art from

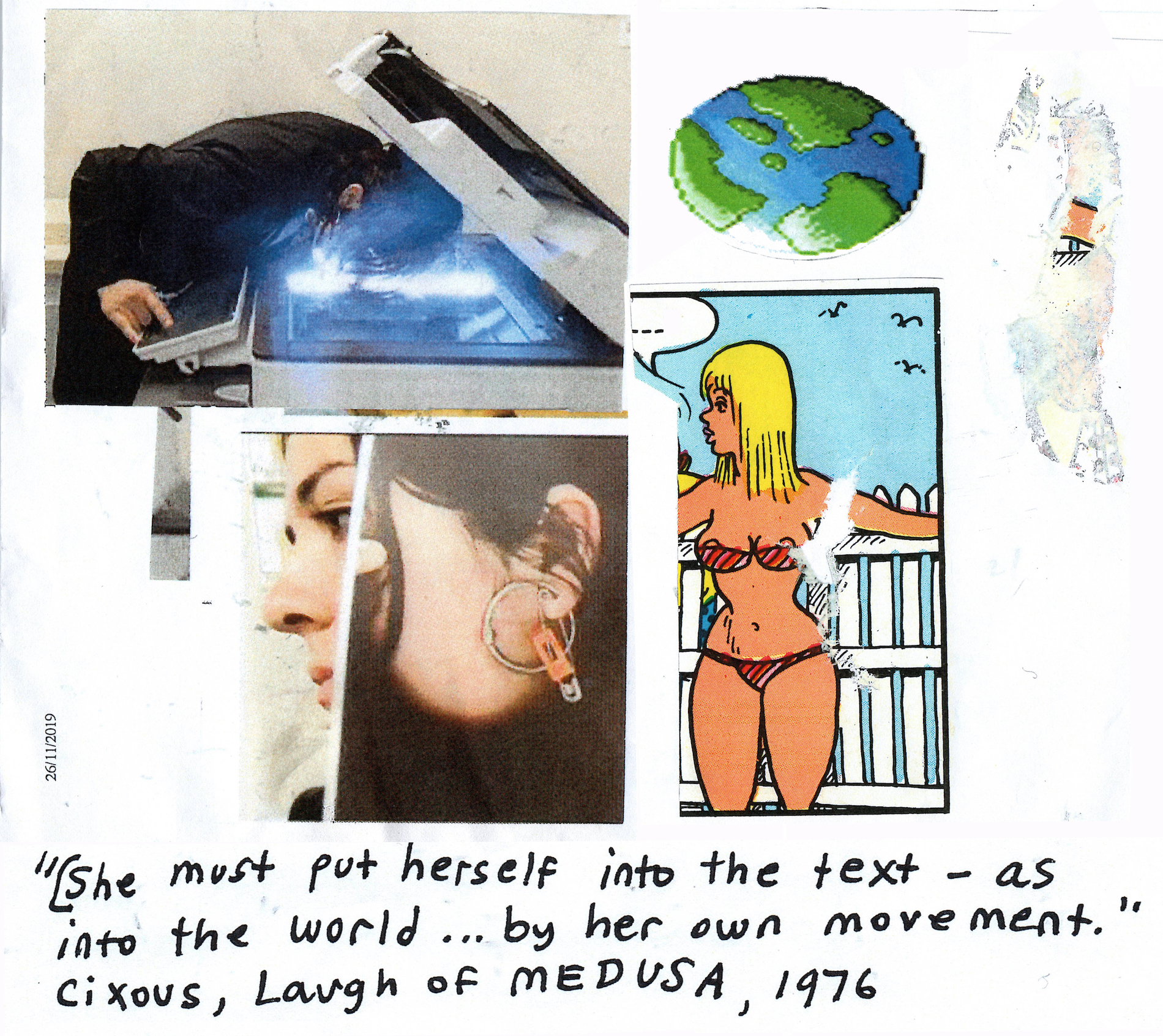

CalArts. There is much ground to cover within her work on the very individual, personal subjects of nostalgia, roots, loneliness, alienation and colonisation. However, when her intentions are boiled and stripped down, her work retains a universality that is all-consuming: mumbling volcanoes, racism, anxiety. All of this. Indeed, a phrase she feels most impacted by, and which perfectly describes the nature of her work, is “ni de aqui, ni de alla” (not from here, nor there). Her references too morph, contort and hop around: from the cluttered, realistic work of Bruegel the Elder, to the catty, big-eyed drama of the Real Housewives of New York. Hicks is “equally moved by Paul Thek’s body of work as I am by a bag filled with plastic dinosaurs for sale at Savers”.

Hicks’ position feels more similar to that of a translator than a traditional artist. She explains how she often feels that “all of the sensory data I process, memories I replay, daydreams I construct in my heart, it’s all somehow the Earth and ancestral data and memory pulsing through me.”

When looking at Hick’s work, more than any other emotion, I feel grief. It is both blaring and quiet. Indeed, Hicks confesses she finds “this version of the world to be devastating. Of all the possibilities that could’ve been on this miraculous gravity-cradled rock, it’s shattering that so much of it runs on carnage, injustice, cruelty and perpetual exploitation. There’s a dense amount of unprocessed grief floating in the air, like a smog covering the planet.”

“All of the sensory data I process, it’s all somehow the Earth and ancestral data and memory pulsing through me”

In addition to grieving, the massive and potent neglect and destruction of nature, there is a war going on at a molecular level for Hicks, too. “I am constantly grieving the violence of colonialism,” she says, “and the mutant ways that I carry legacies in my own body of both the colonised and coloniser.” Touching upon generational trauma, as well as the natural agony of being alive, Hicks feels she “came here (to Earth) already somewhat heartbroken.” This pain transpires in a fine layer of ultraviolet that coats her work. “Humans are self-aware mammals, running around in unsustainable empires fuelled by toxic ideology, over-extracted Earth and Jurassic oils. It’s all so miraculous and so bizarre!” she proclaims.

Throughout her creative practice, Hicks is reminded of her own mortality. I ask what her last words would be. She replies that she hopes they are “Wow, that was beautiful.”