The amount of information in the world is overwhelming. From the database of every “like” ever clicked, to every scrap of code from every cookie that’s been casually accepted while browsing, the sheer quantity of the stuff is enough to boggle even the most dedicated of minds. The impact of excess data on society is starting to be looked at more seriously by artists, sociologists and cultural commentators.

Hito Steyerl points out in Duty Free Art that the NSA surprisingly feels “We’re drowning (not waving) in a sea of data—with data, data, everywhere, but not a drop of information” and even Julian Assange agrees with them: “We are drowning in material.” Not only can an excess of data contribute to exhaustion and anxiety, it also leads to paranoia about what’s hidden in that scramble. What are we not seeing? It must be something. It can’t just be chaos.

Mix in the reach of contemporary mass communication (bots, retweets, chain messages, hashtags and more) and the deliberate propaganda efforts of everyone from advertisers to pro/anti-zionists, and you have an almost foolproof and endlessly adaptable recipe for conspiracy theory. As seemingly more and more people fall down Q-shaped rabbit holes and cheerfully obey the “eat me” labels on whatever pill-boxes they find down there, it seems like a good time to seriously start talking to each other about data, noise, perception, privacy and secrecy.

“What are we not seeing? It must be something. It can’t just be chaos”

It might seem improbable that a cookbook could cut through the thickets of paranoid web-spinning and overwhelmingly large files, but The Leaked Recipes Cookbook by researcher Demetria Glace aims to do just that. JBE’s new publication is illustrated with tongue-in-cheek photographs by food technologist, designer and multimedia artist Emilie Baltz, and is the result of a years-long project on the part of the author to better understand the nature of big data leaks, their origins, impacts and implications, from Pizzagate to Grandma’s praline.

A few years ago, Glace signed up for a project that sends all the leaked emails from the Enron scandal into your personal inbox in chronological order (this can take up to twenty-eight years, if you choose the lowest number of emails per day, which is a still quite excessive forty-nine). You receive these emails, sent by real people, to real people, as though you were their intended recipient, in and amongst your other daily correspondence. Glace lit upon food as her way into exploring and discussing the fraught tensions of this massive amount of data, because, as she points out, everyone has a relationship with food.

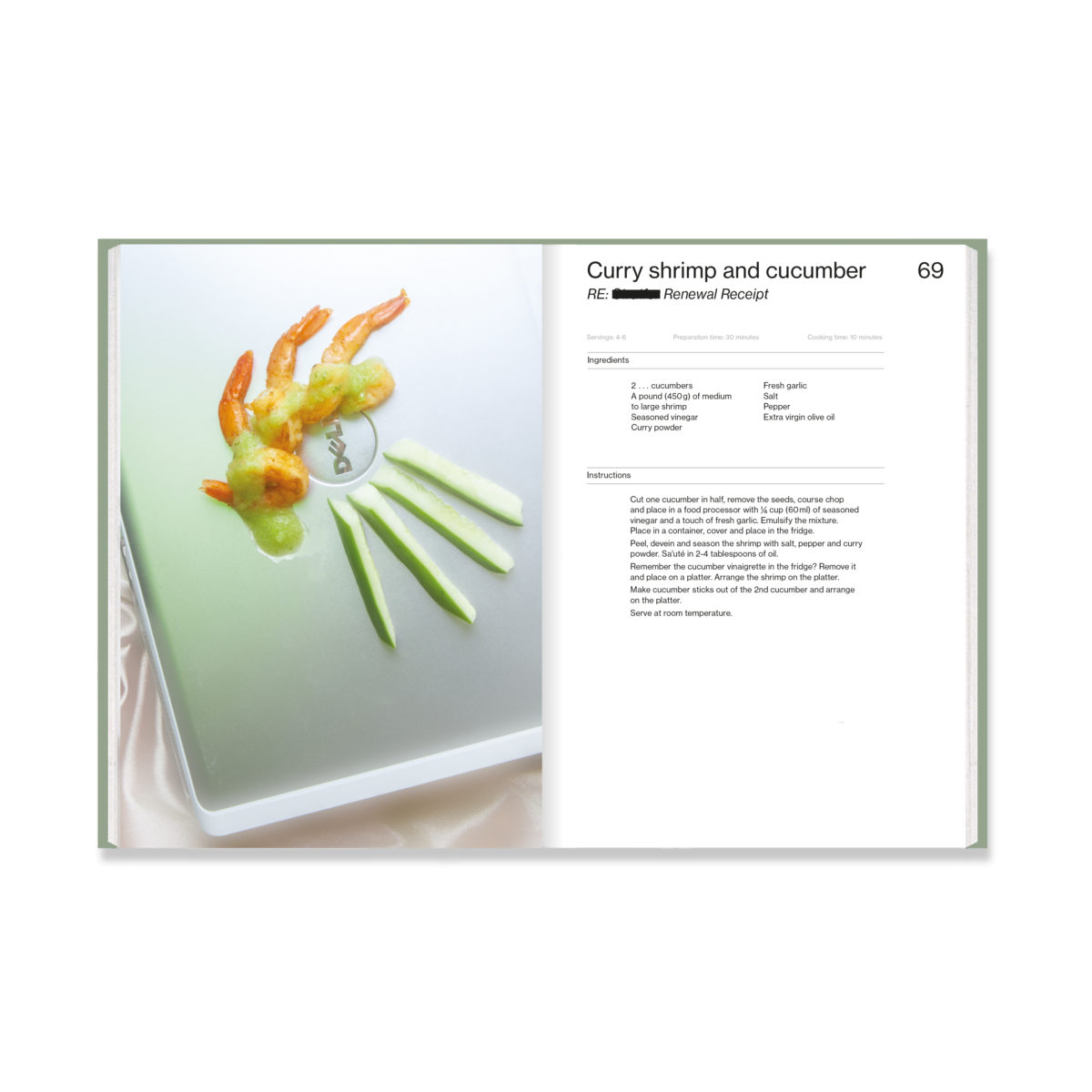

Eventually expanding beyond the Enron emails into a survey of pretty much every major leak of the past 15 years, the cookbook features 52 recipes alongside menus, place settings, playlists (also culled from leaked emails), and analysis: everything you need for a good conspiracy dinner party! Glace also managed to interview some of the original recipe-sharers for their thoughts on being a leakee, using the symbolic relationship between corporate or state secrets and “secret family recipes” (which leak is more traumatic?) to investigate privacy and the nature of “need to know” info.

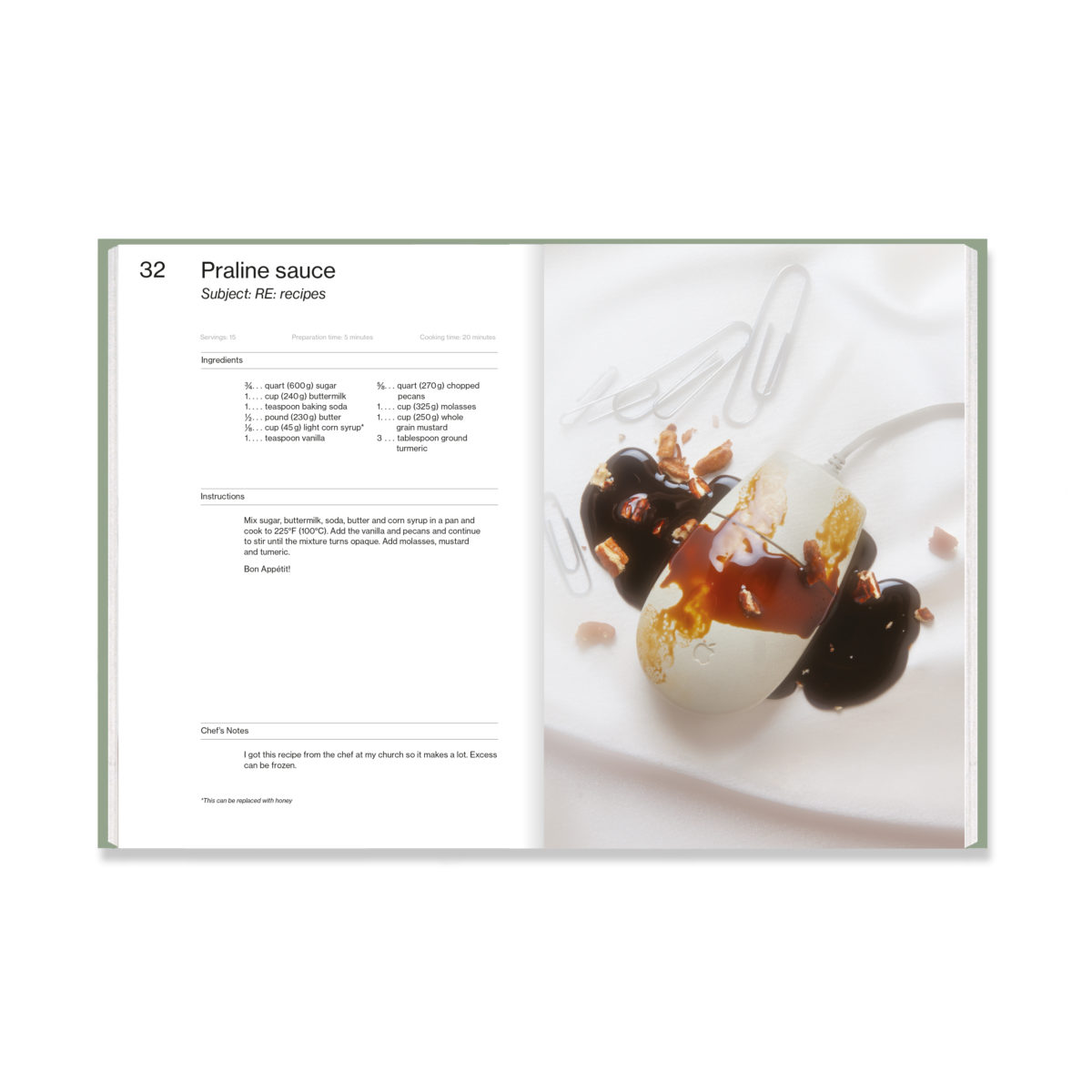

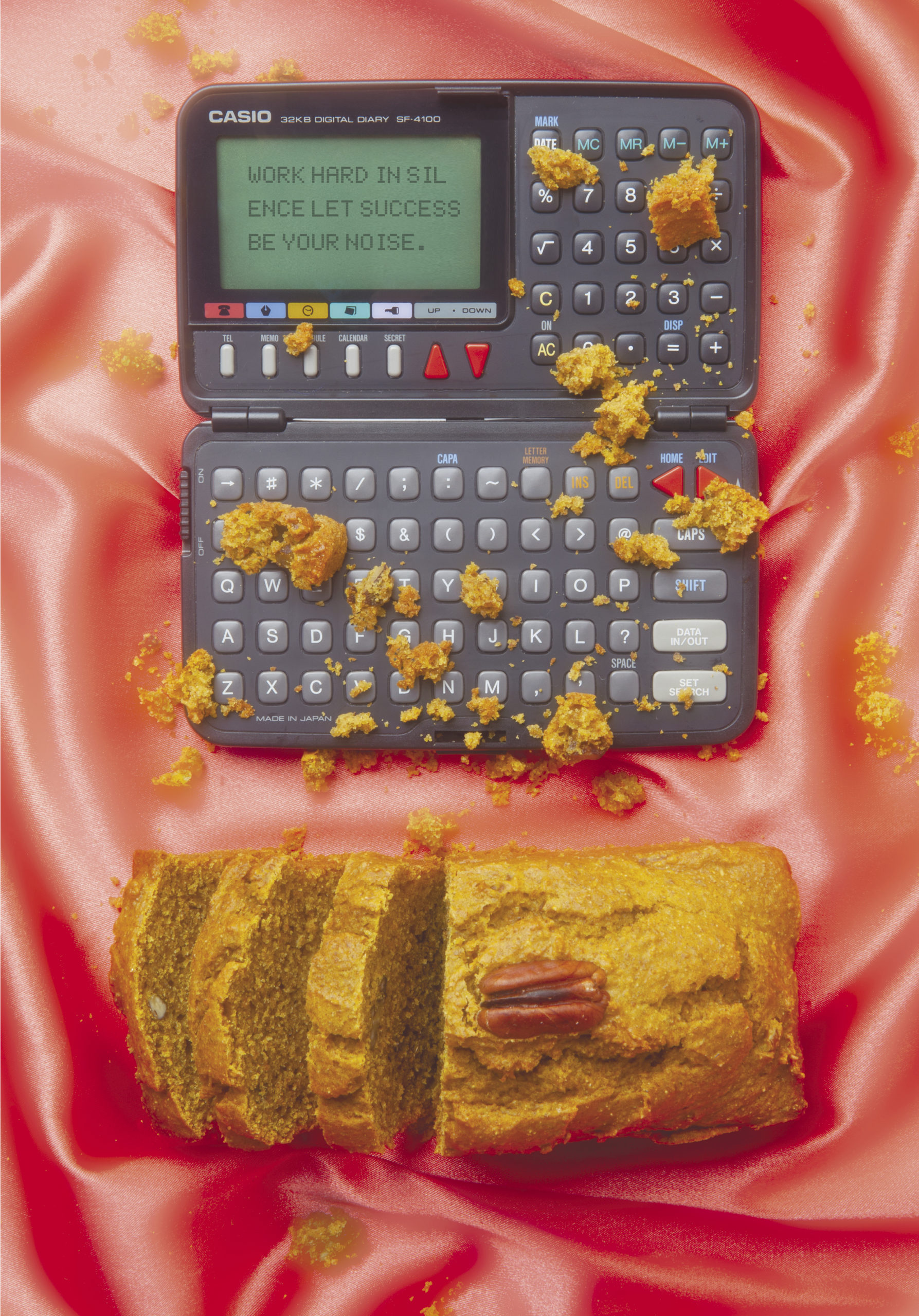

Illustrated with surreally mashed-up clipboards and mashed potato, or file folders and tacos, The Leaked Recipes’ aesthetic nods to the era of Enron, of digital optimism and anxiety: the late nineties. Anyone who remembers the cookbooks of the era will recognise the soft focus photographs of acidically toned food on rumpled satin backgrounds. This nod is to more than an era; many of the recipes are decidedly homely and old fashioned, made up in big batches for church events or work potlucks.

Glace, who cooked every recipe in the book and tried them out on friends, family and dinner party attendees while writing, also points out their geographic specificity. Several of the leaked subjects’ headquarters were physically based in the southern or central United States, so the food is largely American, and often Southern. The Leaked Recipes uses its 52 dishes, place settings, and wryly nostalgic imagery as a way to discuss personal and public privacy.

The chaotic multiplicity of our personal lives and representations (what Steyerl has called “proxy politics”) no doubt makes us all a little more paranoid, and makes the task of getting information from noise more difficult. We want to know the truth, we want to know if we’re being duped, or lied to, as we all sort of suspect we are.

“The Leaked Recipes uses its 52 dishes as a way into discussing personal and public privacy”

But re-humanising the mass noise reminds us that big crimes and cover-ups tend to be quite banal. The truth often involves hundreds of people, who most of the time think they’re only ignoring or covering a small discrepancy or mistake. This is more dull but rather more plausible than, say, everyone involved in the Apollo missions, from janitors to fishermen to small children at Cape Canaveral, being in on the “fake” landing and staying silent for decades.

It also reminds us that most people have their own secrets, their own personal conspiracies, even if it’s just that their followers have never seen them without a filter. At the same time, there’s room to wonder if it would be preferable for pattern recognition software to find it that bit harder to slot you into a watchful algorithm. After all, you have to keep those secret family recipes safe, don’t you?

All images from Demetria Glace, The Leaked Recipes Cookbook, JBE Books, Paris, 2020