In the summer of 1964, civil rights activists staged “wade-ins” on racially segregated beaches in St. Augustine, Florida. Following several years of activism in the lead-up to the passing of the Civil Rights Act, protestors intended to simply march on the beach and enter the water, but segregationists forced them further into the sea, resulting in violent clashes and mandating several rescues. Photographs of the event show agitated bodies hovering just above or in the water—a snapshot of racial injustice that stretched from dense metropolises to the very edges of the country.

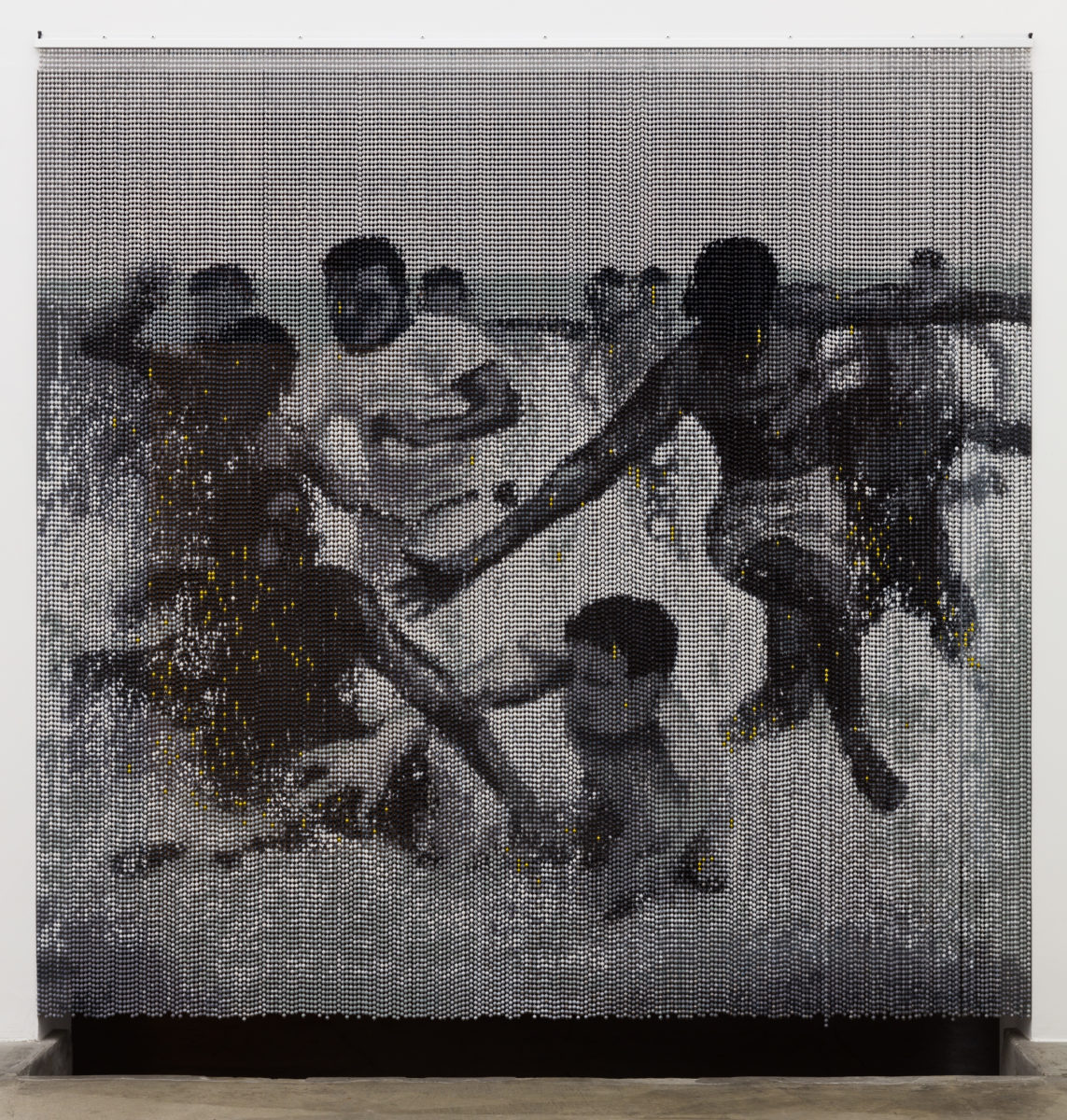

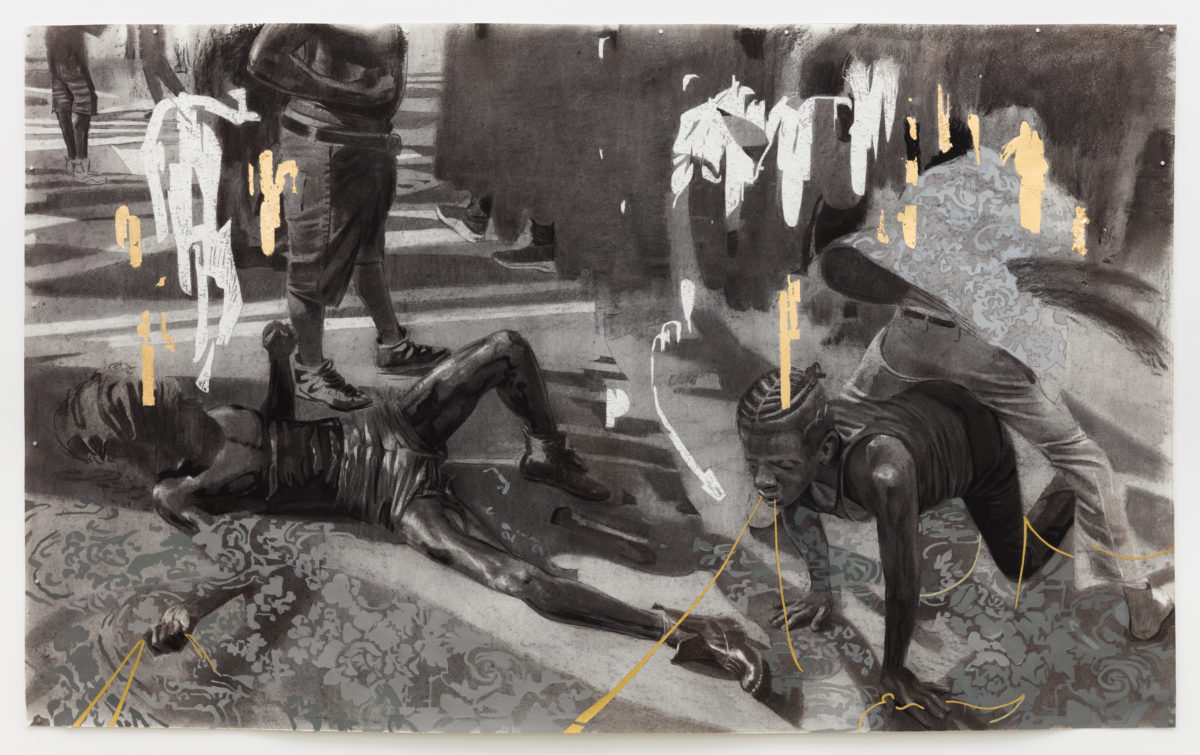

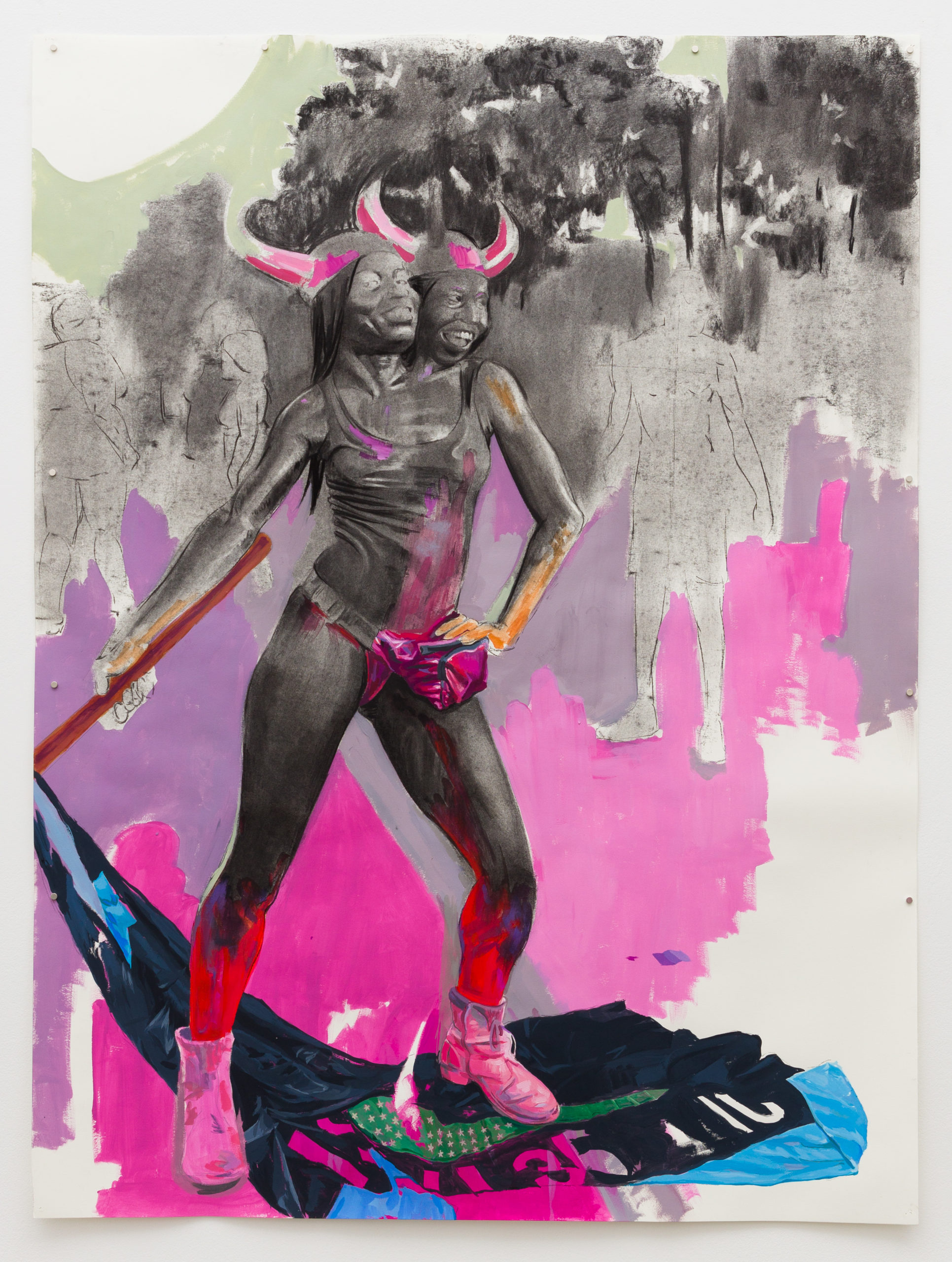

Jamaican-born artist Cosmo Whyte depicts the scene in his exhibition When They Aren’t Looking We Gather By the River, currently showing at Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles. Whyte uses a variety of materials to render the pain and power of protest, choosing a hand-painted beaded curtain to depict events in St. Augustine. Elsewhere, he distorts and fuses figures together in his paintings to convey a certain unreality, though he is all too aware of his work’s contemporary resonances in a year of racial upheaval.

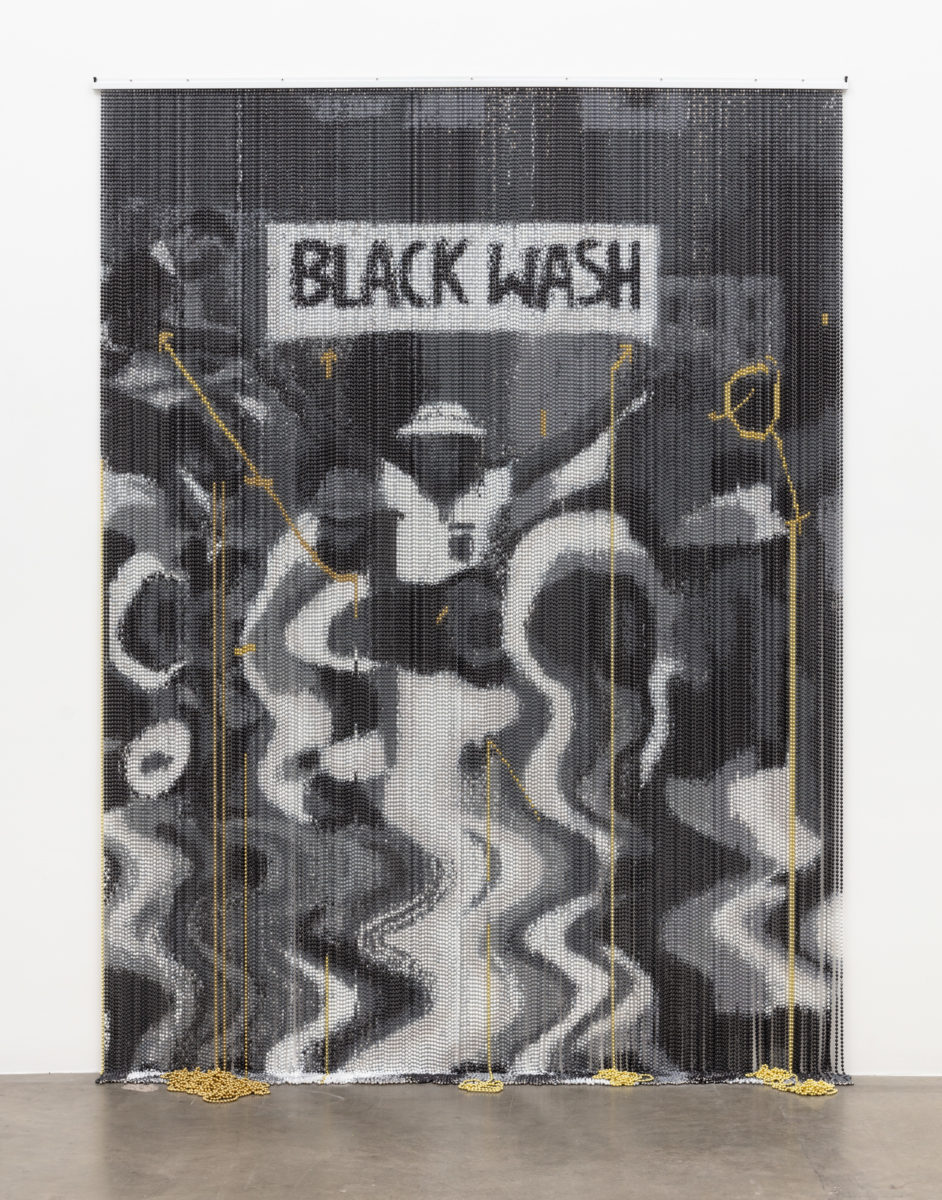

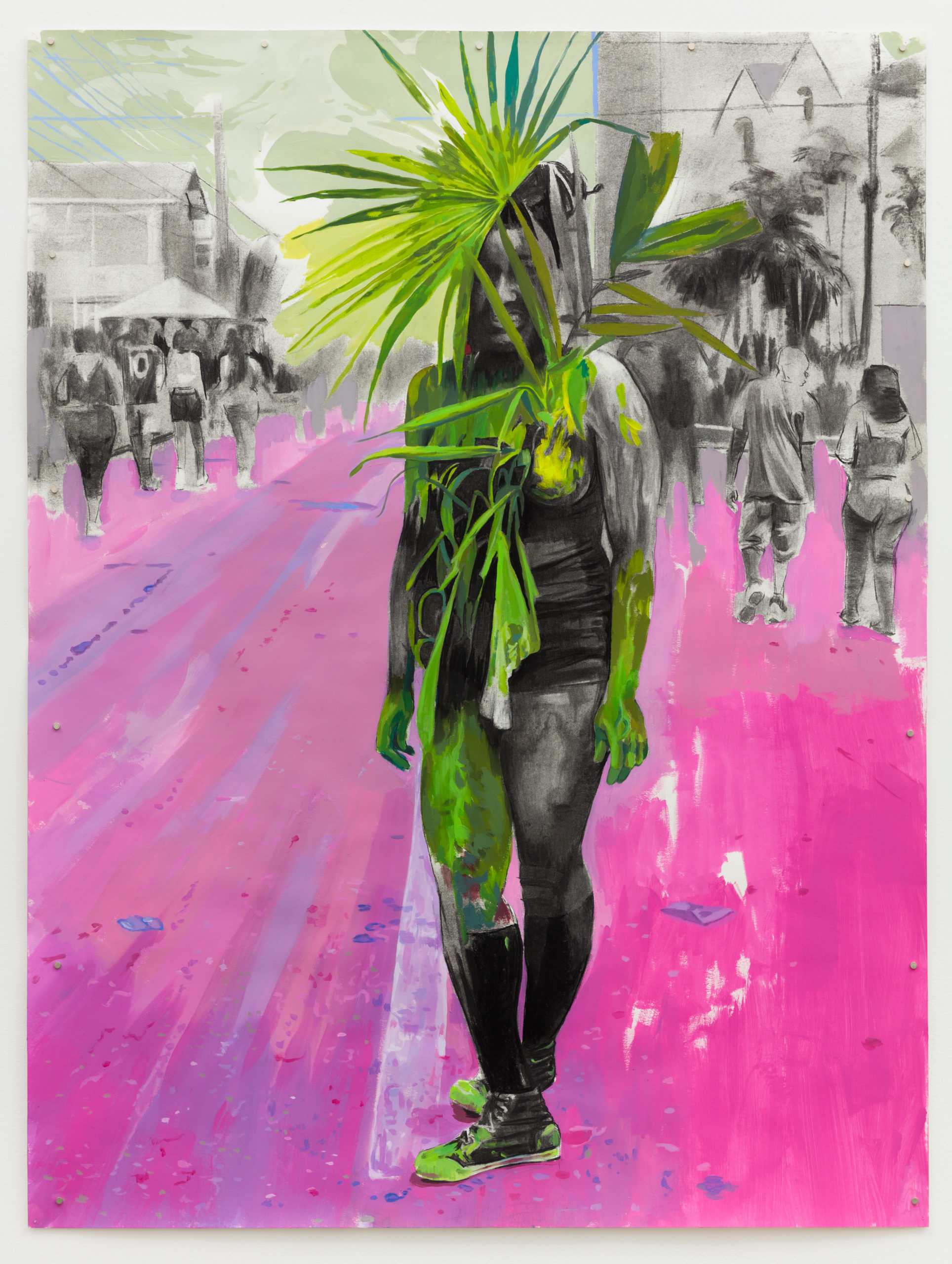

“My studio at the time was four blocks from the CNN centre in Atlanta,” Whyte reflects on the summer’s Black Lives Matter protests. The centre was emblematic of debates around civil unrest as an extension of peaceful protest when all other avenues of resistance have been exhausted. By looking back to an image from the 1981 riots in Brixton, London, Whyte was able to process his emotional response, and in doing so created You Are In The Black Car Burning Beneath The Highway. Elsewhere, Whyte uses flashes of pink and palm tree greens to evoke the spirit of Caribbean Carnivals to create an ongoing lineage of Black protest in his work.

Wading in the Wake references archival images from 1964 of the struggle against segregation. Are you able to talk through your decision to depict this via a beaded curtain? What is the relationship between materiality and meaning here?

Wading in the Wake is part of a larger body of work entitled Breach, which is a series of paintings in the form of beaded curtains that seek to reimagine how we can engage with archival images. As you approach the exhibition, the first piece you encounter at the entrance is Wading in the Wake. By requiring the viewer to move through the beaded partition, I am inviting—implicating—them to become more than mere spectators. As viewers activate what was once a static historical image, they are partaking in a gesture of distortion and illegibility they will see mirrored in some of the drawings on the other side of the curtain.

Beaded curtains are a fixture in domestic spaces in the Caribbean. They are an economical way or partitioning space. My visual imagery of everyday objects is indebted to my upbringing in Jamaica, a place of continued source of inspiration. Unlike the curtains in the Caribbean, Wading in the Wake is made up of nickel-plated beads. There is a noticeable weight and density to the materials. This weight is conceptually reinforced by the image being depicted.

The decision to work in black and white brings out these archival resonances in your work, but you also use bright colours, which seems to signify mysticism or provide a distance from historical reality—is this your intention?

The exhibition seeks to weave a connection between Caribbean Carnival (which historically was a form of protest and one could argue continues to operate as such), other forms of Black diasporic protest and this year’s Black Lives Matter protests. In the studio, these drawings are created in a dialectic manner. So, these bright colours that have stronger associations to carnival started finding their way in drawings of race riots. I am also always mindful of situating my work within an art historical context, so I was also thinking about Robert Rauschenberg’s paintings that incorporated archival images and Radcliffe Bailey’s medicine cabinet mixed media work.

“Bright colours that have stronger associations to carnival started finding their way in drawings of race riots”

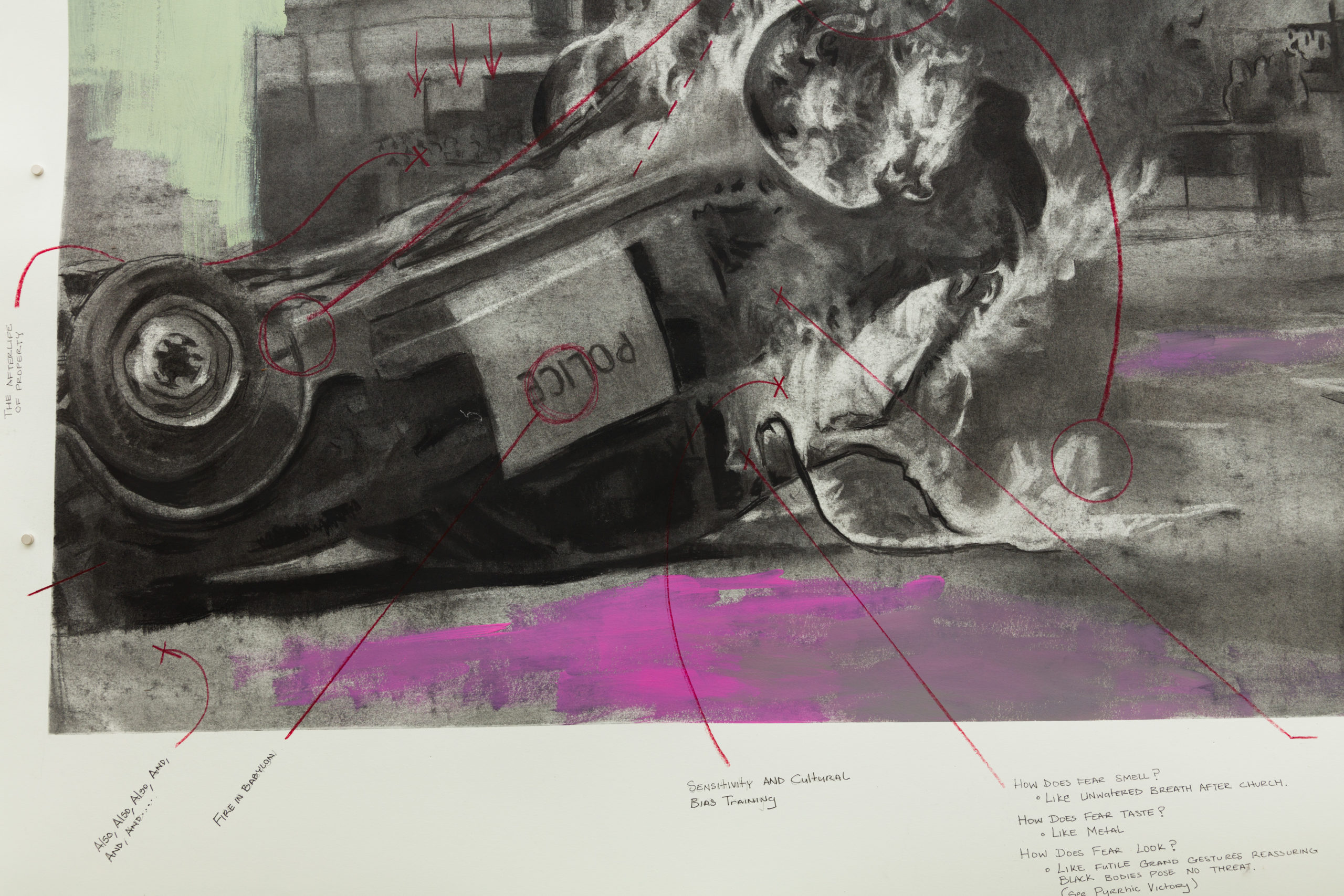

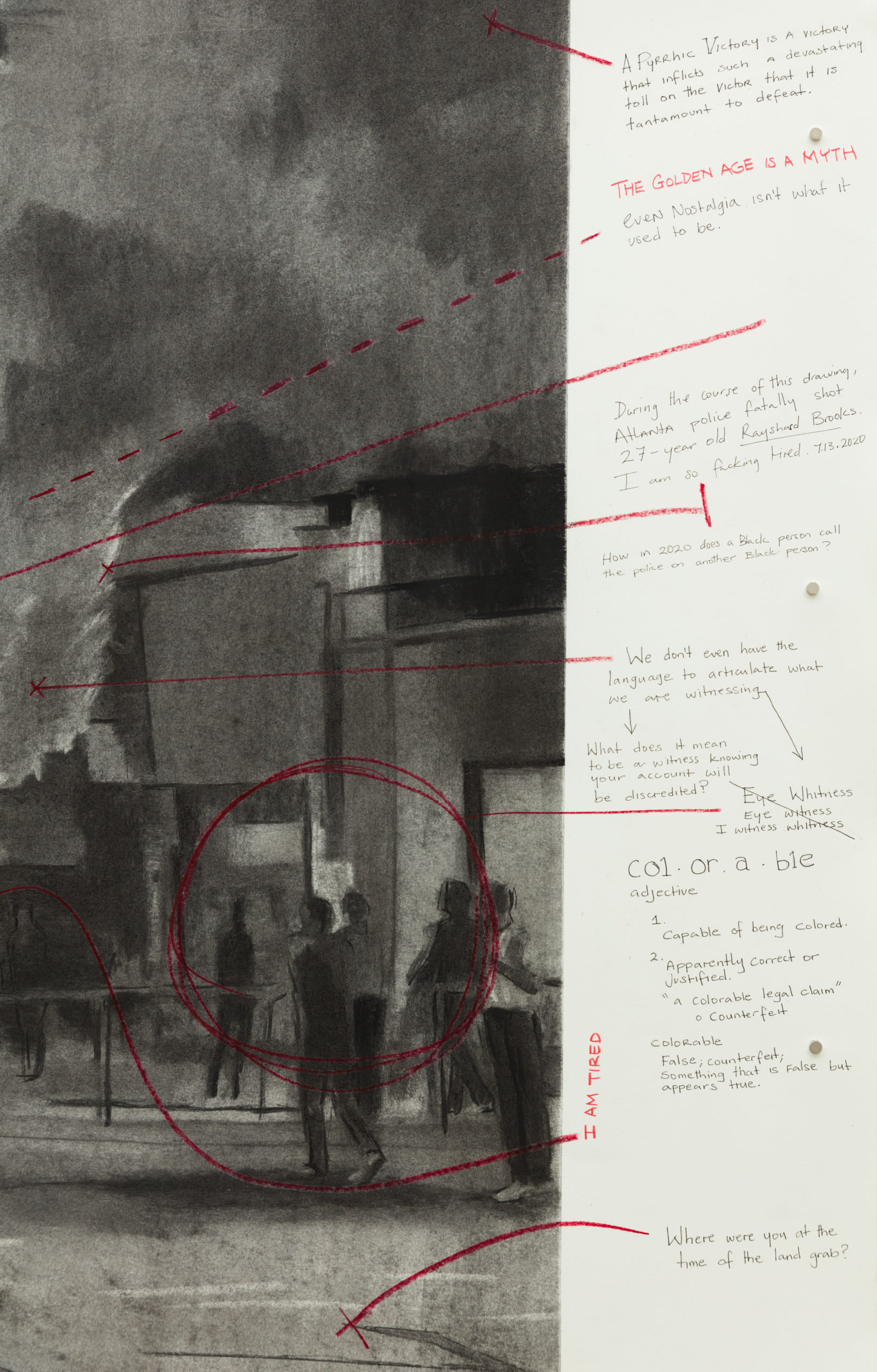

You use annotation to great effect in the exhibition, especially in You Are In The Black Car Burning Beneath the Highway. Can you talk a little bit about this mark-making, and how you think about it in terms of creating a transatlantic understanding of white supremacy and Black activism.

You Are In The Black Car Burning Beneath The Highway depicts an overturned, burning police car, and is based on a photograph from the 1981 Brixton Riots. Using a forensic visual language, I annotated the drawing around its edges, reconstructing the image with emotional and impressionistic commentary rather than didactic text.

My studio/home at the time was four blocks from the CNN centre in Atlanta, Georgia. During the height of the Black Lives Matter protests, the CNN centre became the epicentre of clashes between protesters and the police. My forensic annotations became a way of documenting my emotional response to the shooting of Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks and the heightening tensions in the city.

By overlaying information very particular to this summer’s protest in America with an image of protest in London, I am attempting to create an intergenerational, transatlantic understanding of Black activism and protest. While it is important to honour the differences and nuances of each location and protest, I am also interested in looking at the intersections of Black struggles against white supremacy throughout the diaspora. The title for the work comes from the first line of the poem ‘For Black Children at the End of the World—and the Beginning’ by Roger Reeves published this past June.

“ I am attempting to create an intergenerational, transatlantic understanding of Black activism and protest”

The wider sculptural work in the exhibition seems to be less historically situated and more allegorical. Can you explain its role?

Yes, this is correct. There is one sculptural piece in the show titled Punch Drunk Love. The sculpture consists of one heavily braided shipping rope (which spans around 12 feet) coiled in on itself, and a replica of Queen Elizabeth’s sugar bowl balancing precariously atop the rope. The sugar bowl is filled to the brim with Jamaican rum. Across from this is a rope buoy with a string of golden beads (identical to those in the curtain) entangled in it. The legacy of colonialism looms large in this contemporary conversation about Black agency, liberation and lives mattering.

Much of the work has been created this year, in what has been a monumental period for Black activism in the US. What kind of pressures do you feel that Black artists have been under to respond to these events, and how do you situate your work—and this exhibition—within this?

I cannot speak on behalf of other Black artists. For me this summer posed a series of existential questions: What is the role of the artist in times of crisis? What are the most effective roles of Black artists at this moment? What are the ethical ways of talking about Black trauma, resistance and resilience without perpetuating trauma or resorting to outdated tropes? How am I reconciling my position as both Jamaican, immigrant and American in this increasingly hostile landscape?

There is a very myopic way the media talks about riots, yet it has persisted for generations as a form of resistance. While I am not endorsing violence, I am curious as to what we are overlooking when we dismiss riots as an unnecessary response to injustice and white supremacy?

Cosmo Whyte, When They Aren’t Looking We Gather By the River

At Anat Ebgi until 16 January

VISIT WEBSITE