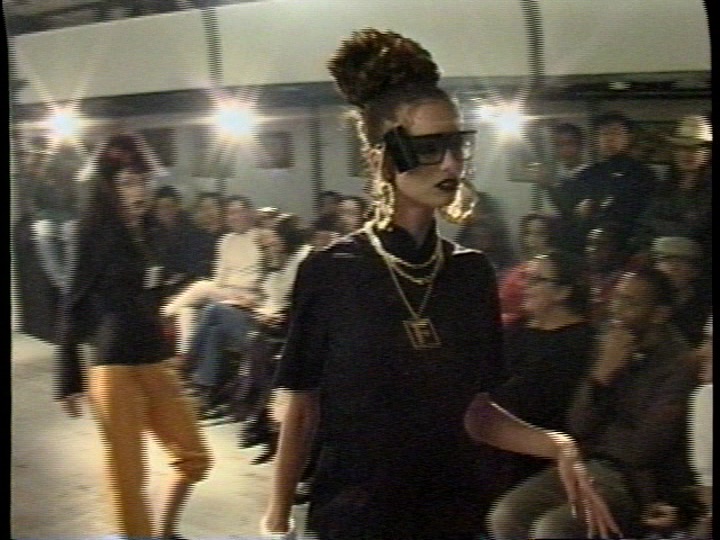

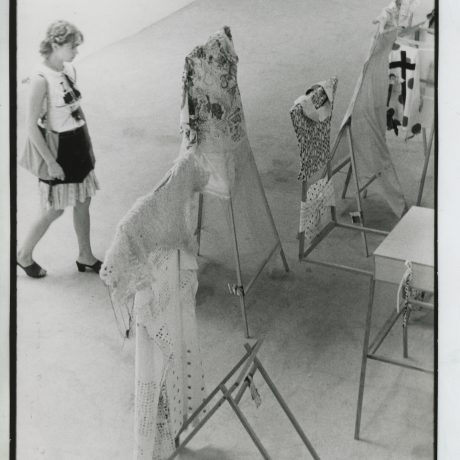

Bernadette Corporation F/W ’95 fashion show. Photo: Cris Moor

The front cover of Fashion Work

by Jeppe Ugelvig shows a smiling figure wearing a white roll-neck top with a label and tag on the front neckline, as if the garment is being worn back-to-front and inside-out. The tag reads “NOT FOR EVERYONE” and the label gives the following directions in the guise of washing instructions: “Dry Clean Only, Made by Artists, 100% for Sale, No Guarantee”.

It’s a work by the collective DIS, a group of young creatives working across New York’s cultural sectors who came together in 2009. Over the next ten years they would run an online magazine, launch their own fashion label, take part in exhibitions in museums worldwide, collaborate with luxury French fashion house Kenzo, and curate the 9th Berlin Biennale.

The story of DIS is one of four that Danish curator and cultural critic Ugelvig uses as a case study in his book. It tells the histories of practitioners who engaged critically with the fashion world, forming new paths for fashion workers, and for the industry as a whole. Developed from a 2018 exhibition Ugelvig curated at the Hessel Museum of Art, New York, Fashion Work

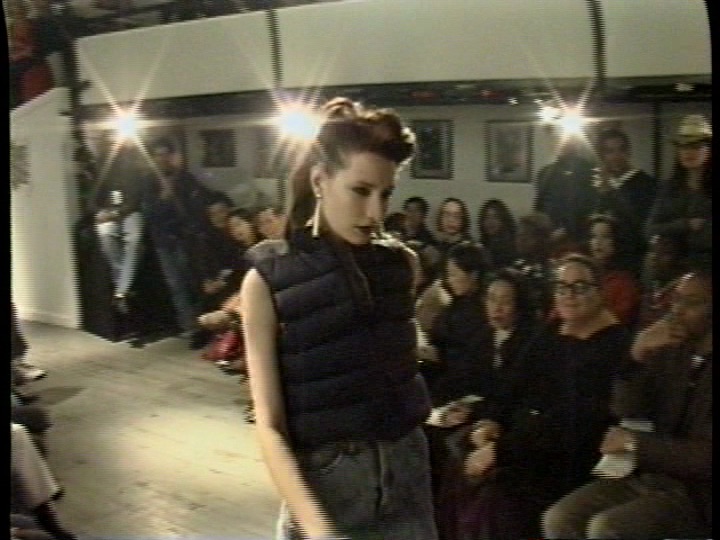

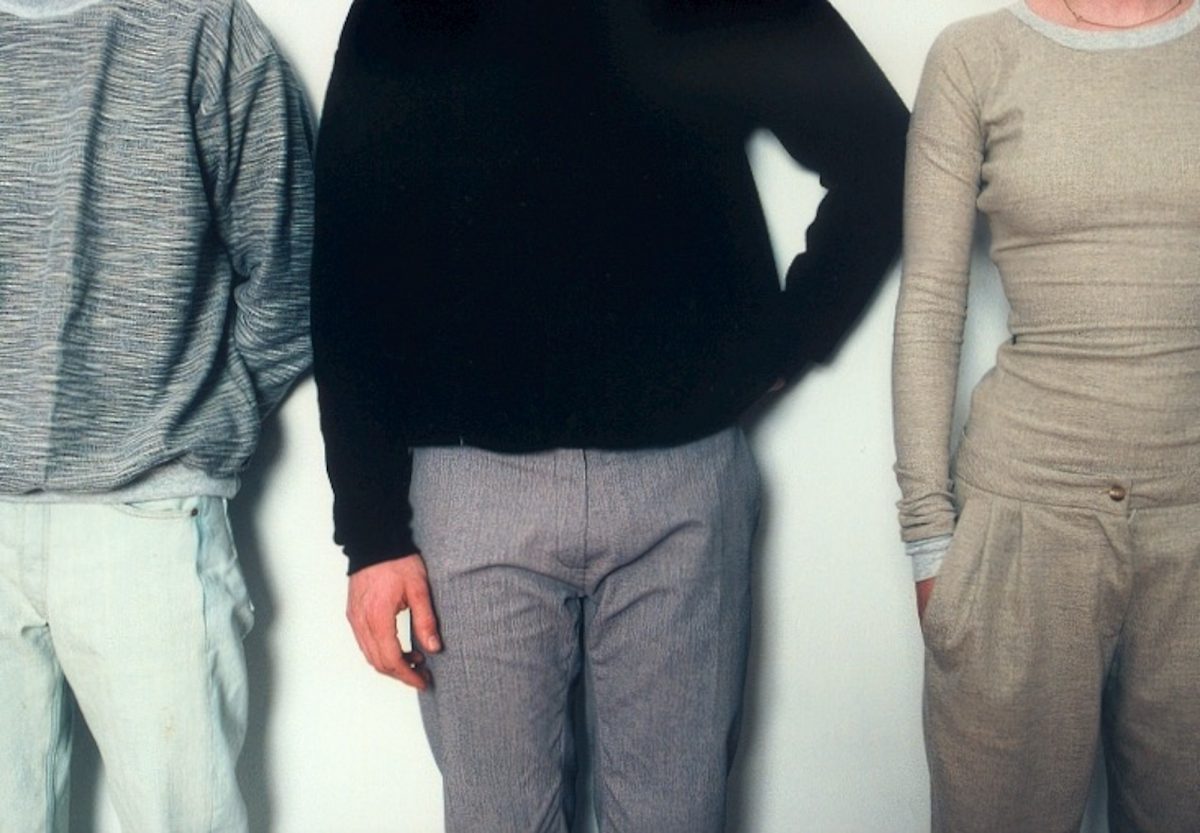

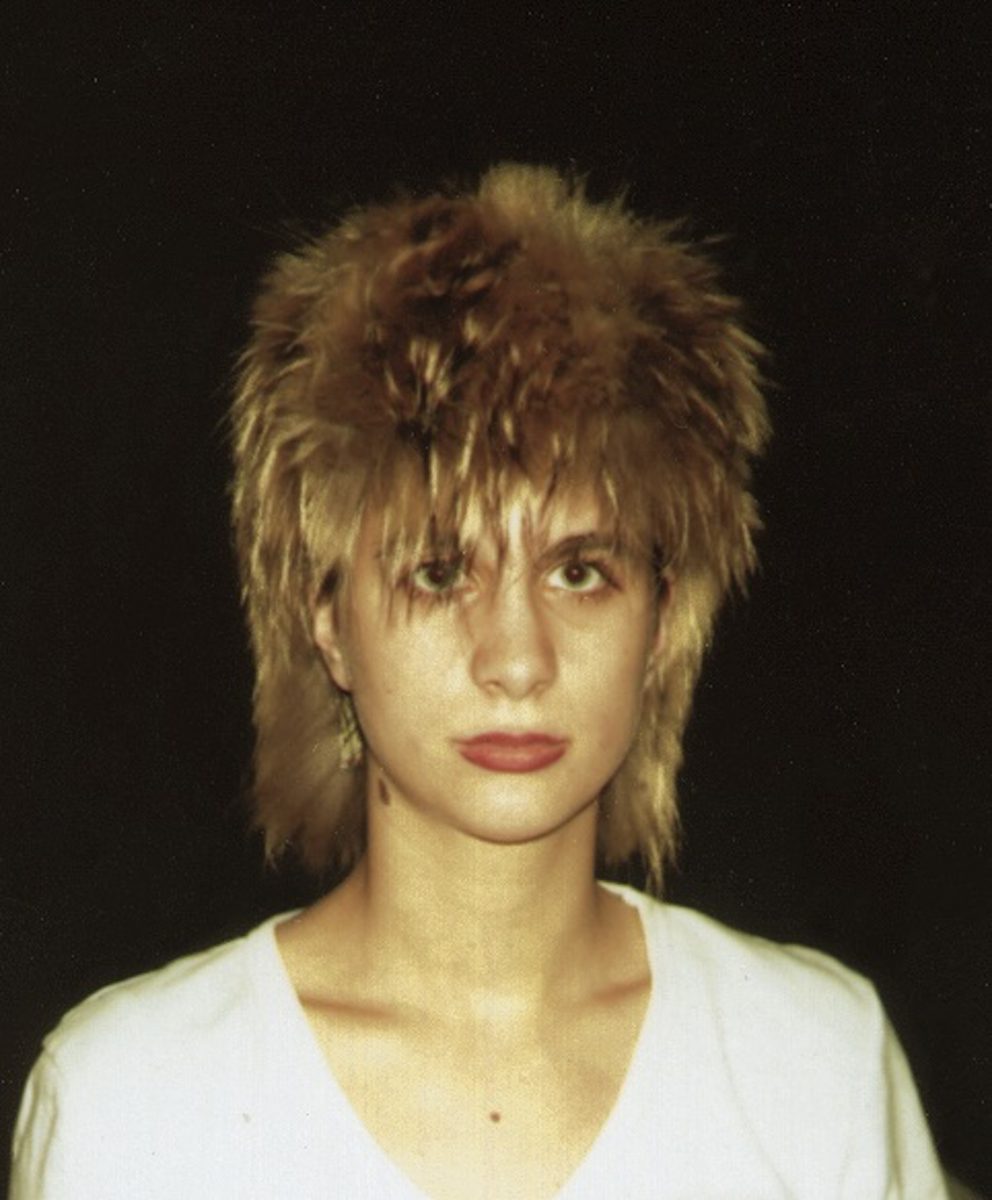

reflects on 25 years (1993–2018) of the complex and overlapping spheres of art and fashion. Illustrated throughout with rarely seen archival material, sketches, glimpses of parties, behind-the-scenes photographs and runway shots, the publication sets out to explore and assess the “work” of groups of opportunistic young creatives.

The intermingling of art and fashion is nothing new. Fashion brands sponsor art fairs, high-profile artists collaborate with fashion houses and museums and galleries host pop-up stores for designers’ collections ,but as Ugelvig points out, these partnerships are usually driven by money rather than critical conversation.

Presented chronologically, Fashion Work begins with Bernadette Corporation, a collective that emerged in the early 1990s in New York. They started life organising parties at the notorious nightclub Club USA using their “faceless and amorphous” moniker to evade the trappings of celebrity and the demands for a marketable identity.

“It tells the histories of practitioners who engaged critically with the fashion world, forming new paths for fashion workers, and for the industry”

The group would organise coordinated group dress-ups and in 1995 re-launched as a fashion brand. They produced their collections on a shoestring, often borrowing garments from sportswear brands and second-hand shops.

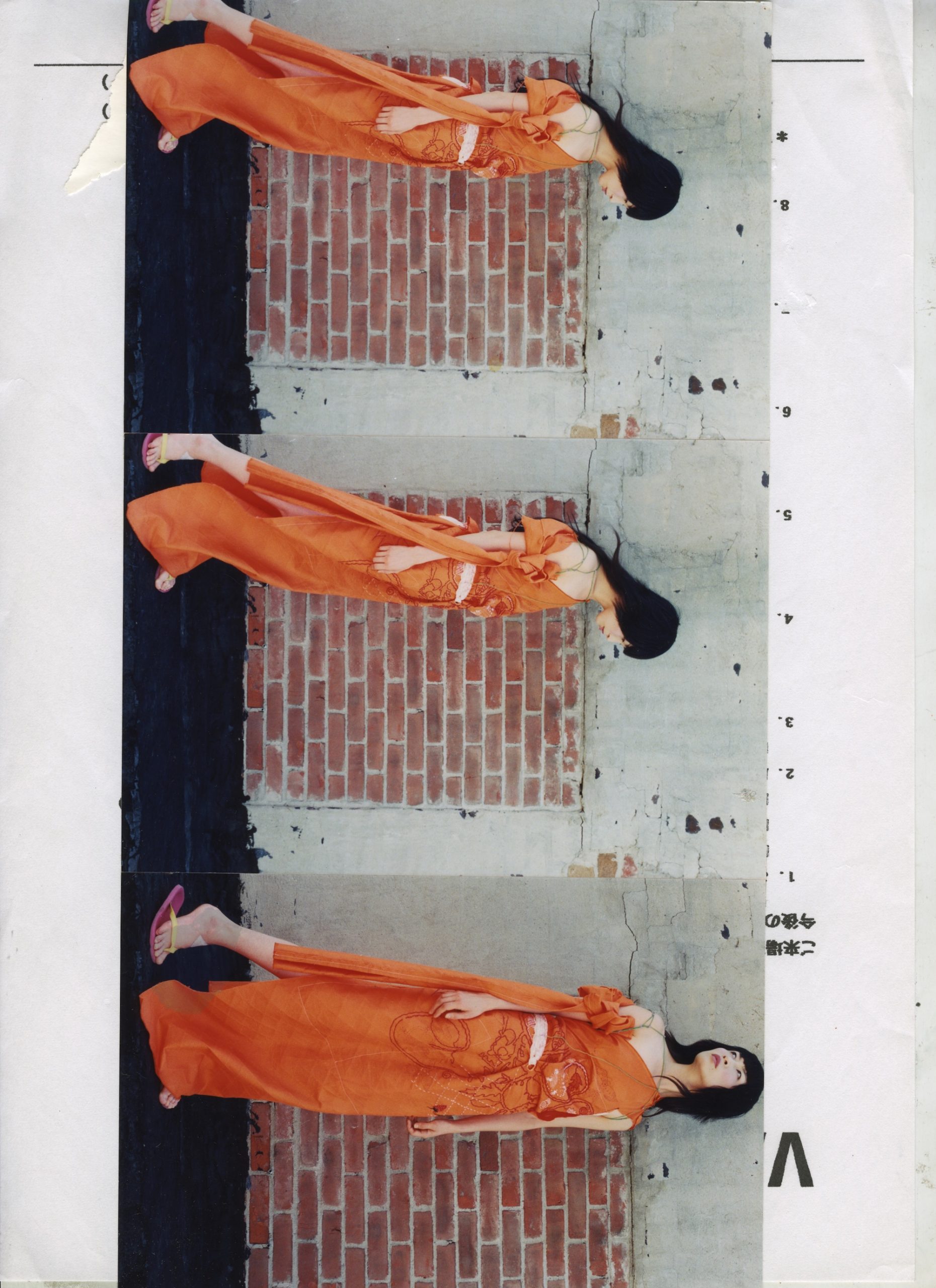

Susan Cianciolo’s RUN (1995–2001) was a label with a “crafty, rag-tag and at times amateurish aesthetic” positioned firmly in the art world but operating within the fashion system (launching collections seasonally to follow the industry calendar). Cianciolo prioritised community and collaboration, her research-led practice leading to new modes of production, presentation and exchange.

“The intermingling of art and fashion is nothing new, but these partnerships are usually driven by money rather than critical conversation”

Ugelvig offers Berlin-based BLESS (Desiree Heiss and Ines Kaag) as a European counterpart. BLESS ignored mainstream fashion’s commitment to seasonal releases and produced singular works rather than collections, prioritising “individuality and subversion through modification and misuse”. For BLESS N°09 in 1999 they infiltrated fashion week guerrilla style, dispersing their designs to friends and colleagues who wore them to shows and parties. They filmed the results and edited them into a 14-minute video.

Part-glossy fashion magazine, part-exhibition catalogue, and part manifesto, Fashion Work tries to expand our definitions of art and fashion, gesturing to the routes that both could take in the future, each borrowing from the other in order to generate something new. It might also encourage us all to reject the megabrands and ready-to-wear models, and try on something a bit more experimental.

Rosa Tyhurst is assistant curator of exhibitions and public programmes at Spike Island, Bristol