Cacao is the simple material which tackles the hypocrisies of the global $100 billion chocolate industry, art world corporate sponsorship and exploitative trade in a show at ScultpureCenter, New York.

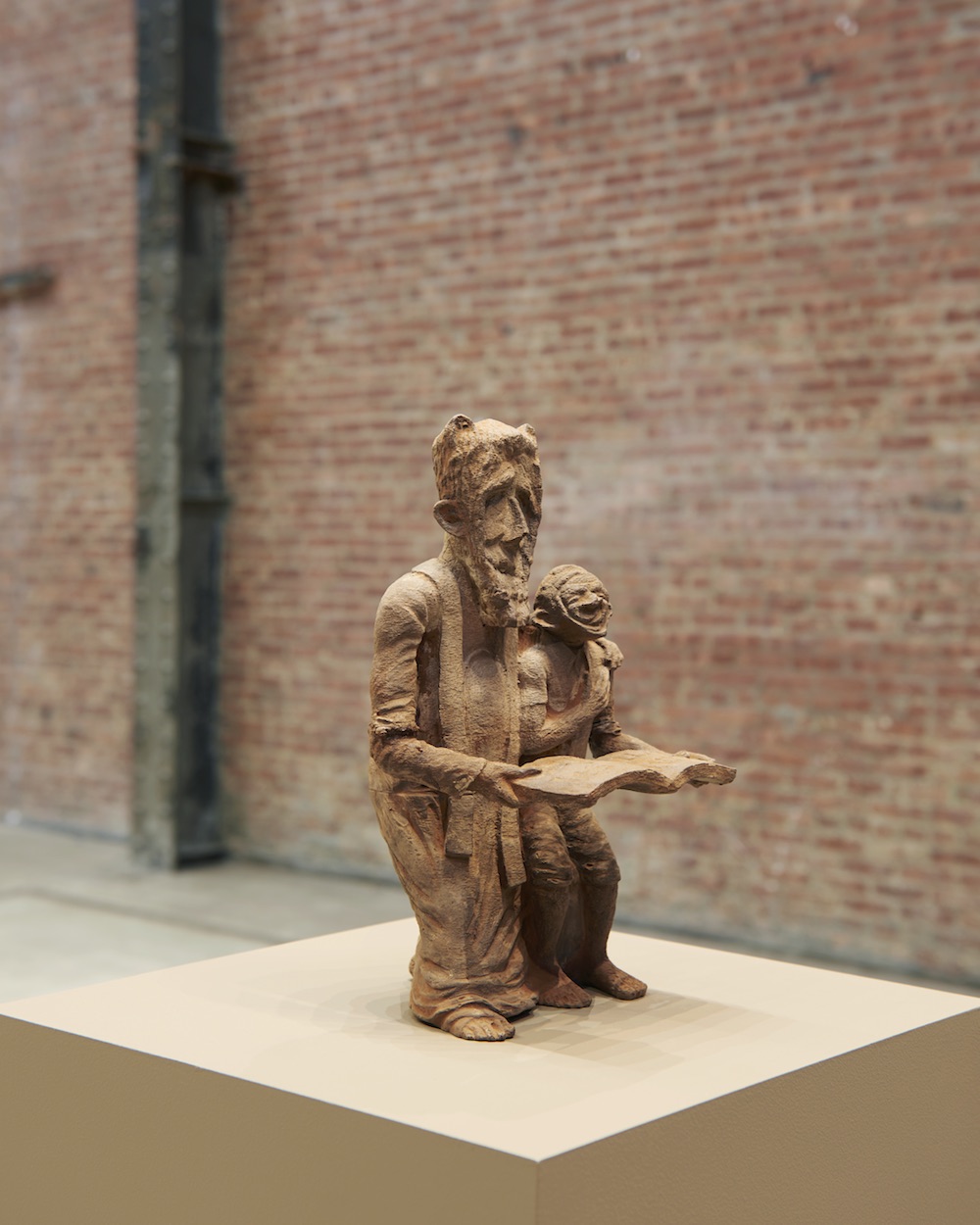

Dutch artist Renzo Martens is the founder of the operation in question. CATPC (Congolese Plantation Workers Art League) began in 2012 as a collective whose artists are plantation workers, creating pieces which are then sold on the global art market. They create representations of themselves, past, present and occasionally reimagined as collectors. The sculptures are first modelled from clay, then scanned and 3D printed in cacao. Their creation offers a reversal of sorts to the usual cycle of things and the profits from sales of works all go back into self-owned agricultural production throughout the Congo.

A couple of years ago it was reported that Martens was moving to eastern Congo with his family to “gentrify the jungle” with news of his five-year plan to open an art gallery there (there were parallels drawn with Klaus Kinski–the figure who builds an Opera House in the Amazon Rainforest in Werner Herzog’s Fitzcoraldo). The time has come, and Lusanga International Research Centre for Art and Economic Inequality opens next month with one leading line of enquiry: Can artistic engagement with global inequality bring economic empowerment to one of the most disenfranchised places in the world?

While sceptics may have dismissed this decision as a stunt in preceding years, the finished space is complex and integrated, posing workable ideas for social and environmental development and calling on the likes of Carsten Höller for donated artworks. It has variously been referred to as a gallery, museum and research centre in associated discussions, but it is “research centre”, proudly included in the title of the space, which seems to sum up the activity the best. Action, not merely representation.

The centre will be built on the site of a former Unilever plantation, which highlights the dubious relationship between the exploitative plantation industry and the art world. Unilever’s high profile sponsorship of shows—as well as wider corporate sponsorship from the likes of BP—is a constant area of conflict.

Further to this, the collective, the museum and the overarching Institute for Human Activities address and question the voices which we typically hear in the art world. When we hear about exploitation, how rarely does it come directly from the exploited?

‘Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (Congolese Plantation Workers Art League)’ runs until 27 March at SculptureCenter, New York. LIRCAEI opens in March 2017.