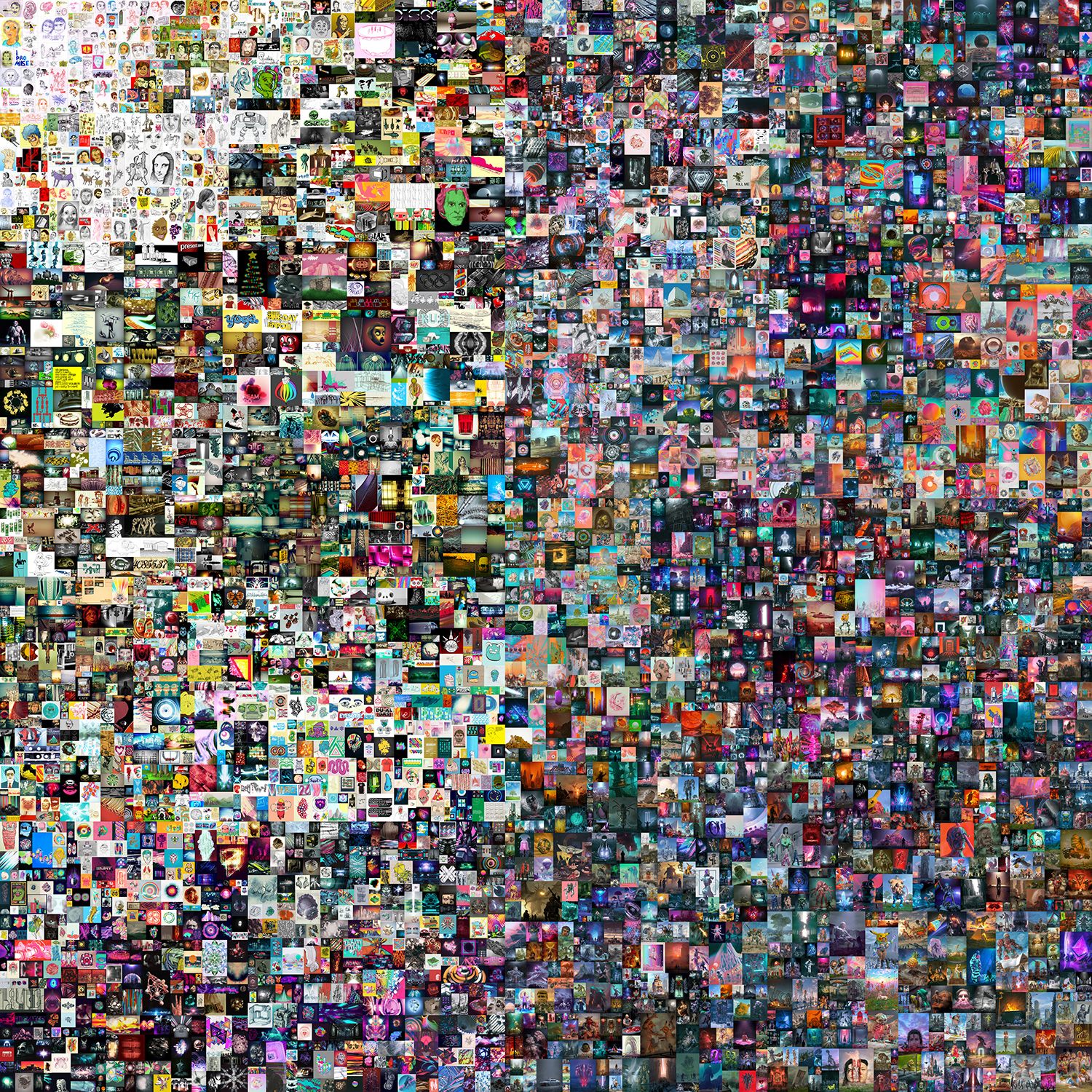

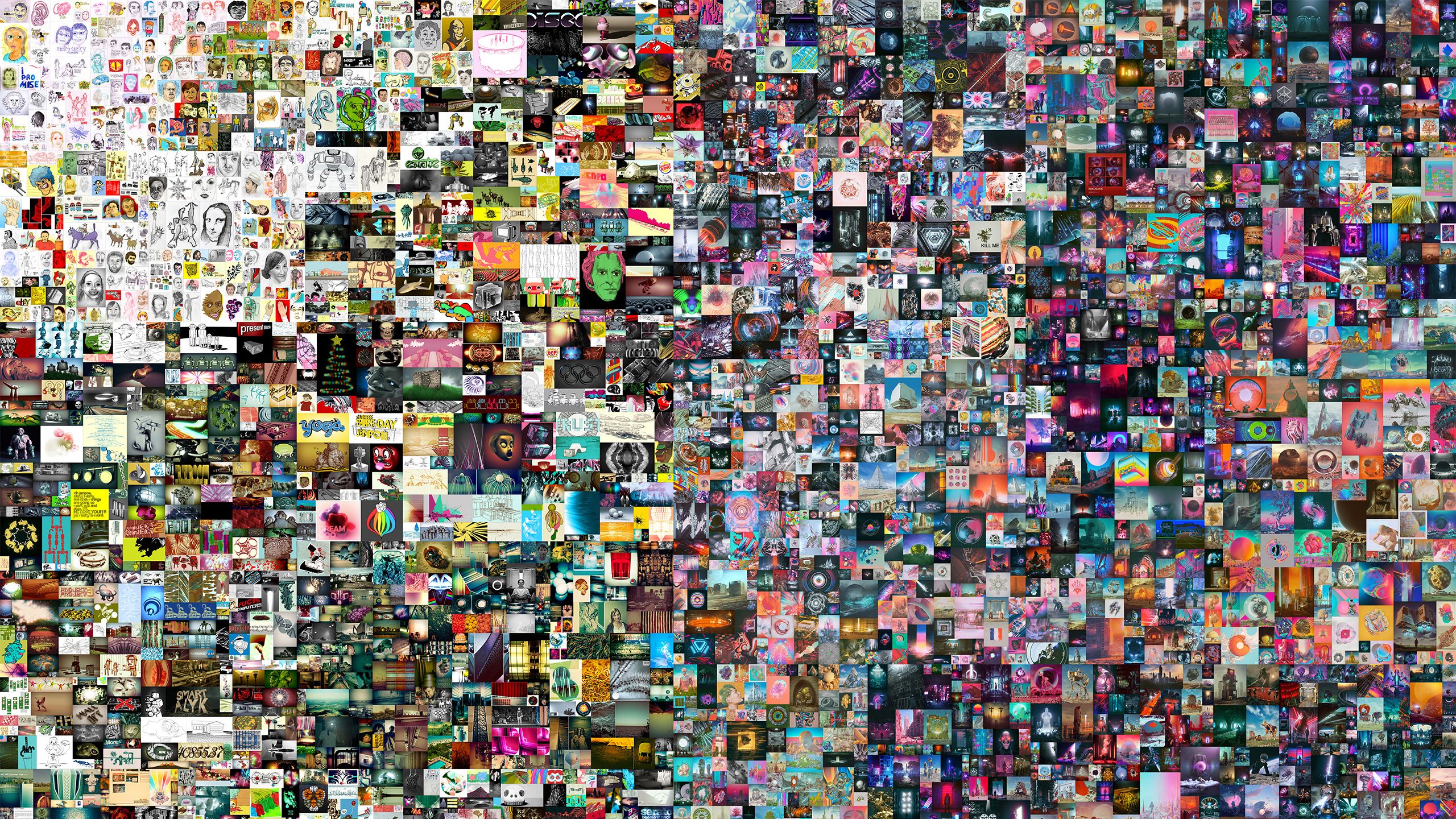

Everydays — The First 5000 Days, an ongoing digital art project by graphic designer Mike Winkelmann (who goes by the pseudonym Beeple), has recently been on the baffled lips of countless artists, journalists and tech bros. Typically Winkelmann works with brands such as Nike and Vogue, as well as celebrities like Justin Bieber and Nicki Minaj. But now, with auction house Christie’s, he is making history with an unprecedented sale. The two-week-long auction, which runs from 25 February to 11 March 2021, is the first time that a digital work has been offered for sale by a major auction house who are also accepting cryptocurrency as payment.

This is due to a technology called NFTs, which stands for non-fungible tokens, meaning the digital artwork can be verified on the blockchain as unique, and therefore sold in the same way that traditional art forms like painting and sculpture are. Shortly before this, in December 2020, Beeple made $3.5 million over one weekend—the second time he had ever put his art up for sale. Now, with an art world giant behind him, the price could go much higher. The current bid on Beeple’s Everydays is $9.75 million, breaking his own record and setting a new high for digital art. The sale has generated big debates around money and technology, and how the two are shaping the future of art.

Winkelmann is an artist deeply committed to the irreverent. His website and Instagram account, with 1.8 million followers, both bear the word “crap”. His outline for Everydays, which began in 2007 and continues today, sounds almost like an apologetic disclaimer: “The purpose of this project is to help me get better at different things.” He uses a huge library of 3D models to produce a new image daily, often referencing the news with a committedly slapstick satire: Trump features naked; a hench Elon Musk takes a dog for a walk; cartoon characters from various franchises are rendered strange, ugly and all too real. Beeple’s world is the body horror of meme culture; a flash-in-the-pan melodrama of video games made by an apocalyptic preacher. They are often disgusting and always unapologetically weird. But are they interesting as “art”?

The backlash to NFTs has been fierce. Many have noted the immense environmental impact of the energy burned when crypto art is registered on the blockchain, a process referred to as “minting“. Joanie Lemercier, an artist who often makes works addressing the climate crisis, hoped to reduce his carbon footprint but ended up using the equivalent of his studio’s energy consumption over the past 2 years in just 10 seconds to make six pieces of crypto art. How this can be mitigated is a hotly disputed issue, but extensive research already exists for greener alternatives—it just doesn’t appear that leading companies such as SuperRare and NiftyGateway care about the extraordinary environmental costs.

“Beeple’s world is the body horror of meme culture; a flash-in-the-pan melodrama of video games made by an apocalyptic preacher”

Beyond the problems with the technical process, it is evident that those reaping the rewards are deeply unrepresentative as a whole. At a time when the traditional art world is wrangling with racial injustice and ecological collapse, a group of Silicon Valley-styled crypto-evangelists have heralded a great new disrupted future that is, unsurprisingly, making big profits for a group of white men. Legacy Russell, author of Glitch Feminism, described this as “violent re-brand” of the next wave of “toxic dude net art”.

In a Medium post which quickly went viral, game and software artist Everest Pipkin struck a chord when they called for a “total moral rejection” of NFTs. The technology introduces artificial scarcity to generate profits from art on the internet, something deeply at odds with the original utopian dream of a place as far away from Wall Street as you could imagine. Critic Brian Droitcour, writing in Art in America this month, recalled how other artists interested in the internet in the 2010s “folded an artwork’s market potential into its conception”, namely the process-orientated paintings of Zombie Formalism and post-internet art’s wholehearted embrace of online circulation. If NFTs remain a technical detail of how art is bought and sold then they’re arguably about as interesting as a consignment form.

The market is leading the art, or at the very least, the hype currently overshadows any critically engaging approach or alternative strategies. Yet it is precisely because blockchain technology facilitates ownership—as well as additional means of authorship and community —that it is ripe with critical potential. The “free internet” didn’t liberate us from capitalism as once was hoped but only further entrenched its power. In light of this failure, we need a more nuanced language around the role that NFTs could play in how artists access resources, navigate institutions and cultivate relationships around their practice. How can artists continue to use NFTs to explore and redefine what ownership means in the context of art, and how can we trial alternative economies which centre community and exchange?

“We need a more nuanced language around the role that NFTs could play in how artists access resources”

All too often art history is presented as a story of changing styles and tastes without acknowledging the economic forces that shape artists’ lives. It is important to recognise the social dynamics that can influence who makes art, how they make it and why. Many still cherish, often nostalgically, the internet as a kind of commercial wasteland—a place where people spend time, connect and engage in projects in a way that is impossible to monetise. Yet this purity is artificial and often supported by other forms of employment, like a conventionally ‘boring’ day job alongside a fun side gig, or a career launched from the hype generated by passion projects. When we think about the political context of an artist, we should look to how they navigate the world as much as what they tell us they believe about it. NFTs will undeniably create new economies and shape old ones, but exactly what impact they will have remains to be seen.

Some early examples of how NFTs can facilitate a politics of art on the blockchain have already taken place. Many have noted how crypto art can facilitate smart contracts, ensuring the artist will receive a cut from any future sales. Artist Sara Ludy has taken this a step further, negotiating a contract with her gallery for future NFT sales which would see 35 percent equally divided between gallerist and staff, with each making a 7 percent profit.

In recent years, others have explored the potential and politics of blockchain technology, as encapsulated by new media art non-profit Furtherfield’s 2017 book Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain. Artistic collective !Mediengruppe Bitnik’s Random Darknet Shopper

(2014-16) used an automated bot to purchase random products online with Bitcoin to be delivered to a gallery space and exhibited to the public, highlighting questions of authorship and autonomy. Artist and researcher Primavera De Filippi

’s Plantoid (2016) invited donations which were then used to commission new artworks from other artists, leveraging the technology as an alternative business model for artistic production and collaboration. Artist and writer Alice Bucknell’s E-Z Kryptobuild (2020) video offers an unapologetic critique of the politics of cryptocurrency, drawing connections between property speculation and liberatarian ideas in the face of the climate crisis.

“Some early examples of how NFTs can facilitate a politics of art on the blockchain have already taken place”

Artists interested in the internet have long played with the gaps between the physical and the digital, and with the concept of authorship when augmented by disparate audiences through screens and galleries. In this context, the status of originality that an NFT asserts seems increasingly bizarre. Despite the rarity which the blockchain can verify, a digital file can continue to multiply and circulate through an abundance of duplicates, edits and versions. What constitutes art is a constantly negotiated concept, with fraught battles existing around the ownership of art—particularly how it circulates through private and public spheres. It is at these tensions and dividing lines that productive debates are able to emerge.

The collision of art and money often conjures the most cynical embrace of the two, bringing to mind figures such as Warhol and Koons, but it is a mistake to give so much weight to the market. In 1969, artist Lee Lozano began Real Money Piece, a provocative performance as part of her long-running Language Pieces series. When friends, collectors and curators visited her studio, Lozano would, as described in her notes, “open a real jar of money and offer it to guests like candy.” She recorded people’s responses, highlighting the taboos around wealth and pointing to greater inequalities that were overlooked in the scene at the time. She identified currency as a social medium rooted in existing power structures.

In the future NFTs will inevitably support artists in the production of new work, particularly digital projects which have long struggled for exhibitions, commissions and support from established galleries and institutions. This shift in who gets funded and how will impact the future of art and transform the lives of artists—for better and for worse—and raises important questions around inclusion, accountability and responsibility towards the climate.

In a reaction against the excesses of the market and the overreach by crypto-bros, an all-too easy ‘block-scolding’ (as coined by artist and graphic designer David Rudnick) has come to dominate and define the conversation. But beyond the rightful criticism, NFTs present an exciting conceptual terrain to redress the financialization of life and society. An artistic medium in the waiting, they offer a point of departure to create alternative economies rooted in digital life. There is much more work to be done. It can’t end at an auction result.