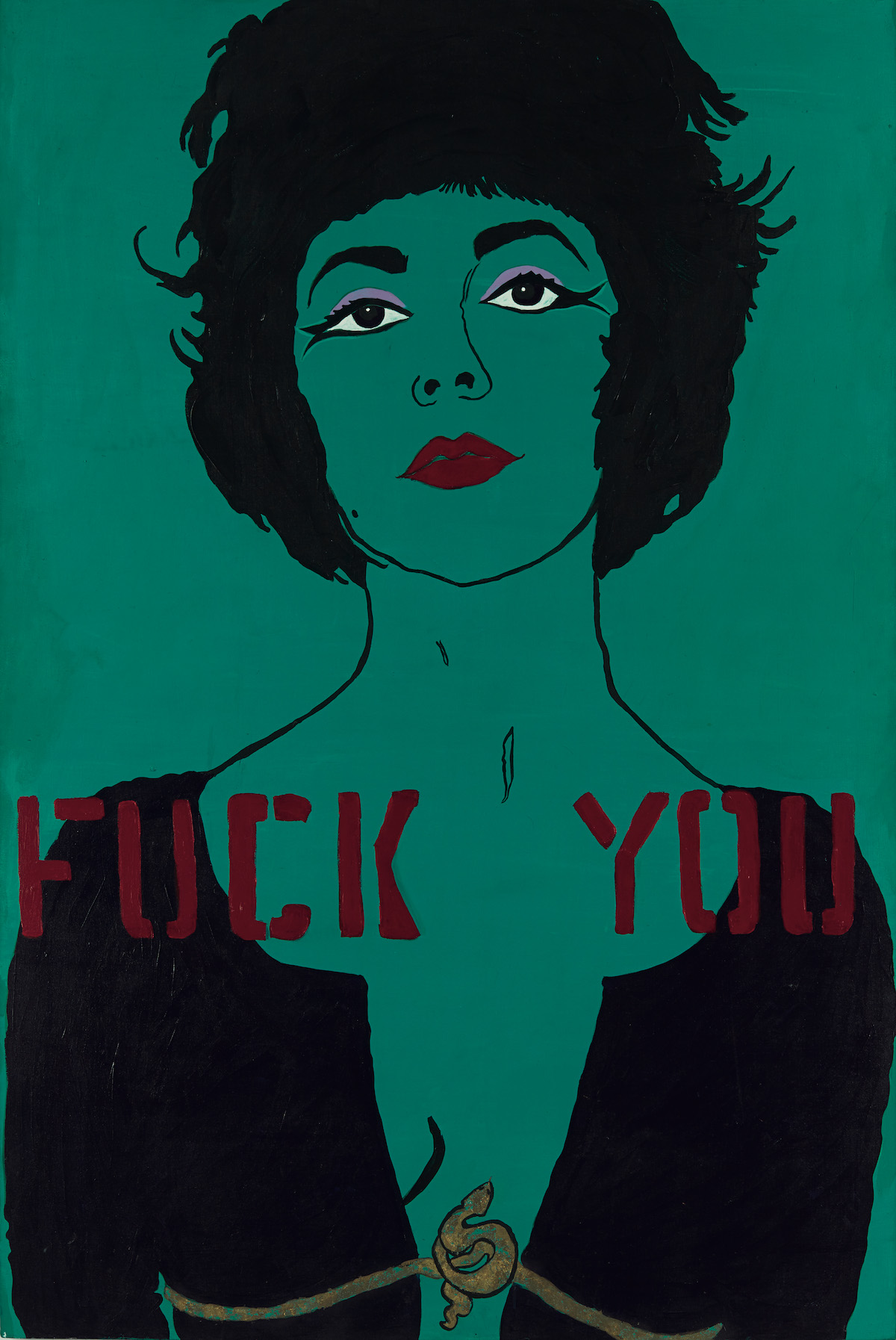

Ethical curating is the act of talking back. As cultural critic Bell Hooks put it, “Speaking is not solely an expression of creative power; it is an act of resistance, a political gesture that challenges politics of domination that would render us nameless and voiceless.” To “talk back” as a curator means to break the rules established by Western and male-dominated institutions. It means to practise a code of ethics that counters persistent under-representation of artists who do not fit the mould, and to get others to think about why this matters. “To talk back is to liberate one’s voice and to empower oneself. We need more talking back, and a continued stream of it, as it’s the only way change will come,” says Maura Reilly, founding curator of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, when I meet her in the New York springtime.

There is no obvious solution but in her new book, Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics of Curating, battle armour to help fight inequality within this “rigged” system is offered up. For Reilly, “statistics are often the most powerful tool to educate folks about inequalities.” The numbers don’t lie. In the re-opening of the Tate Modern in London in 2016, of the 300 artists represented in the re-hang of the permanent collection, less than a third were women and fewer still were non-white, according to Reilly. Meanwhile in 2015, at the inaugural exhibition of the opening of Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in its new location, similar statistics were recorded. But, says Reilly, it is the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York that gets “the worst grade for gender and race discrimination”. In 2004, of the 410 works in the fourth and fifth galleries in the re-opened permanent collection, only sixteen were by women and even fewer by non-white artists.

“To talk back is to liberate one’s voice and to empower oneself. We need more talking back”

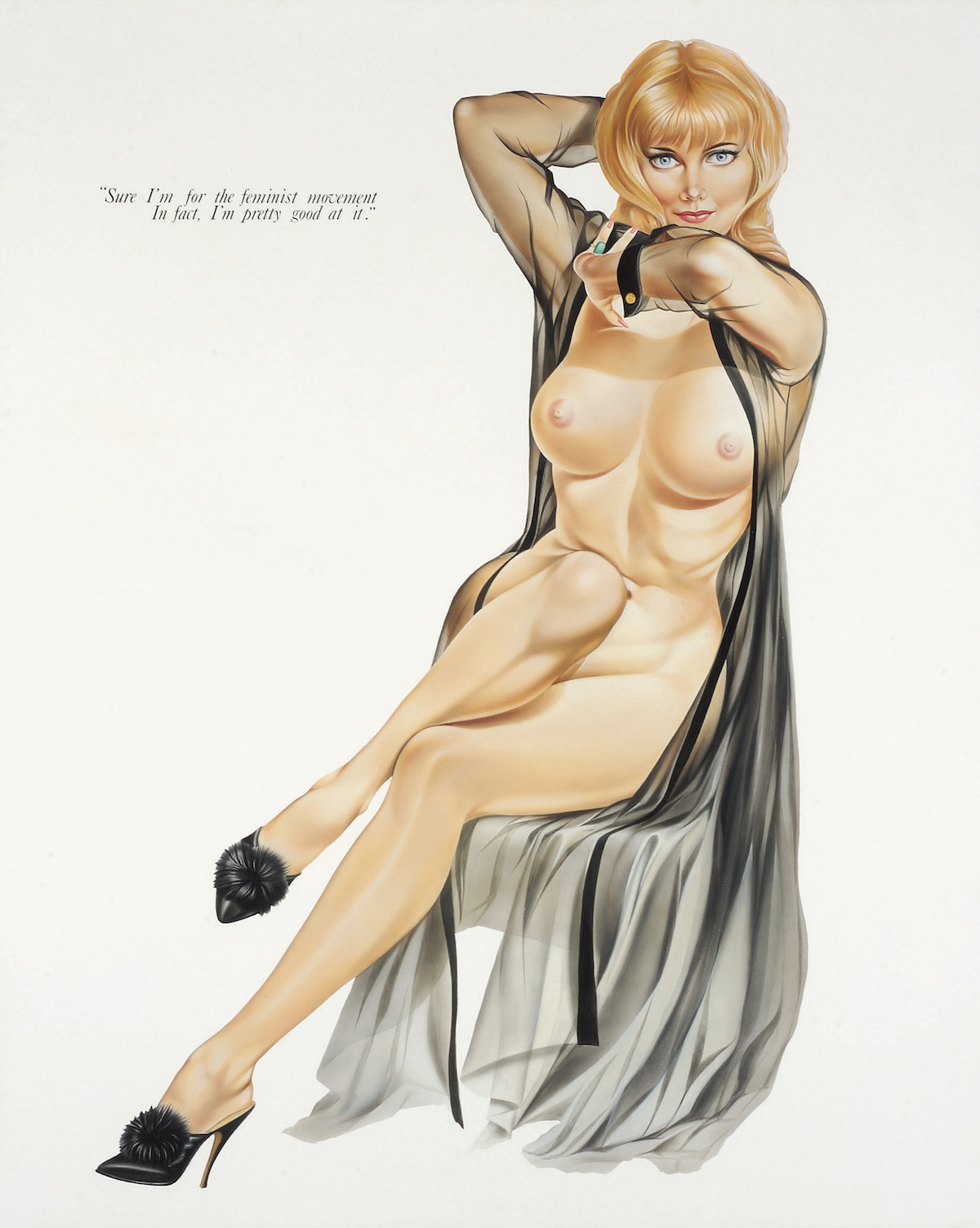

With data this dismal, exhibitions that cut through the hegemonic structures are nothing short of political. One example came in 2007, when Cornelia Butler curated the exhibition Wack! Art and the Feminist Revolution, that went on to have a two-year run. It examined the legacy and foundations of feminist art and featured works by 120 artists from twenty-one countries, with no strict chronological or geographical narrative. It was historical, says Reilly, because its “tremendous inclusiveness was credited with positing an alternative history of art from 1965 to 1980”. The exhibition was a statement against what is traditionally considered to be the “story” of modern art and, as critic Ingrid Rowland wrote at the time, “the general spirit is infectiously exuberant in its eagerness to conquer the world, not just the art world, and set it to rights.”

For decades, Reilly has been working against this gender imbalance, fighting on the front lines of arts activism from within. Through exhibitions, such as Burning Down the House and The Fertile Goddess, she has developed a manifesto for change through action. As a woman in a position of power in the art world, Reilly is clear about her responsibility. “[It is] to always live my life as a person deeply rooted in ethics and equality, whether it be in the way I hire staff, manage a board, flush out an exhibition schedule.” The fruits of this manifesto are a testament to her success. In 2004, she curated the interdisciplinary exhibition project called QUE(E)RIES in Zurich. Instead of showing classical products of LGBTQ art, it discussed “trends, joys and dilemmas in contemporary queer practices”. Meanwhile in 2007, she launched Global Feminisms: New Directions in Contemporary Art at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art; the first exhibition and public programming space in the United States devoted entirely to feminist art.

“Though boundary-pushing work is being done every day to redress this imbalance, Reilly believes the battle for equality in the art world will not be over in her lifetime”

Curatorial activism is one approach for change but that doesn’t let the rest of us off the hook. Change must also be incited outside the boundaries of the art institutions. Reilly calls on artists—and the general public—to agitate and make noise. “In order to institute broad cultural change we need a multitude of voices pushing back against the mainstream (read racist and sexist) art world system,” says Reilly. After all, it doesn’t just fall to curators, it is also the responsibility of galleries, art collectors and the media to push this agenda forward. “Artists can challenge their gallerists to take on more ‘Other’ artists into their rosters; collectors can demand more diversity.” Meanwhile, feminist activists such as the Guerilla Girls and Pussy Galore have protested gender and race disparities for years with their public shaming campaigns which hold galleries to account.

Though boundary-pushing work is being done every day to redress this imbalance, Reilly believes the battle for equality in the art world will not be over in her lifetime. But this doesn’t mean we should give up. “With the alt-right and psychologically imbalanced individuals in power, activism is more important now than at any other point in my lifetime,” says Reilly. She is encouraged by movements like #OscarsSoWhite and #MeToo because “folks are loudly speaking up against inequities, and fighting back, arguing loudly that ‘enough is enough’.”

Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics of Curating by Maura Reilly

Published by Thames & Hudson

VISIT WEBSITE