Gabriel Lester Where Spirits Dwell 2014. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Gabriel Lester

Self-proclaimed maverick JULIANA ENGBERG has staked out a core role for herself in the Australian art world, introducing international artists, supporting the nascent local scene, shaping institutions such as the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, and standing at the helm of festivals and biennales. She talked to NATASHA HOARE for a new book about the changing role of the curator.

This feature was originally published in Issue 27. You can buy a copy of ‘The New Curator: Researcher, Commissioner, Keeper, Interpreter, Producer, Collaborator’ at Laurence King Publishing.

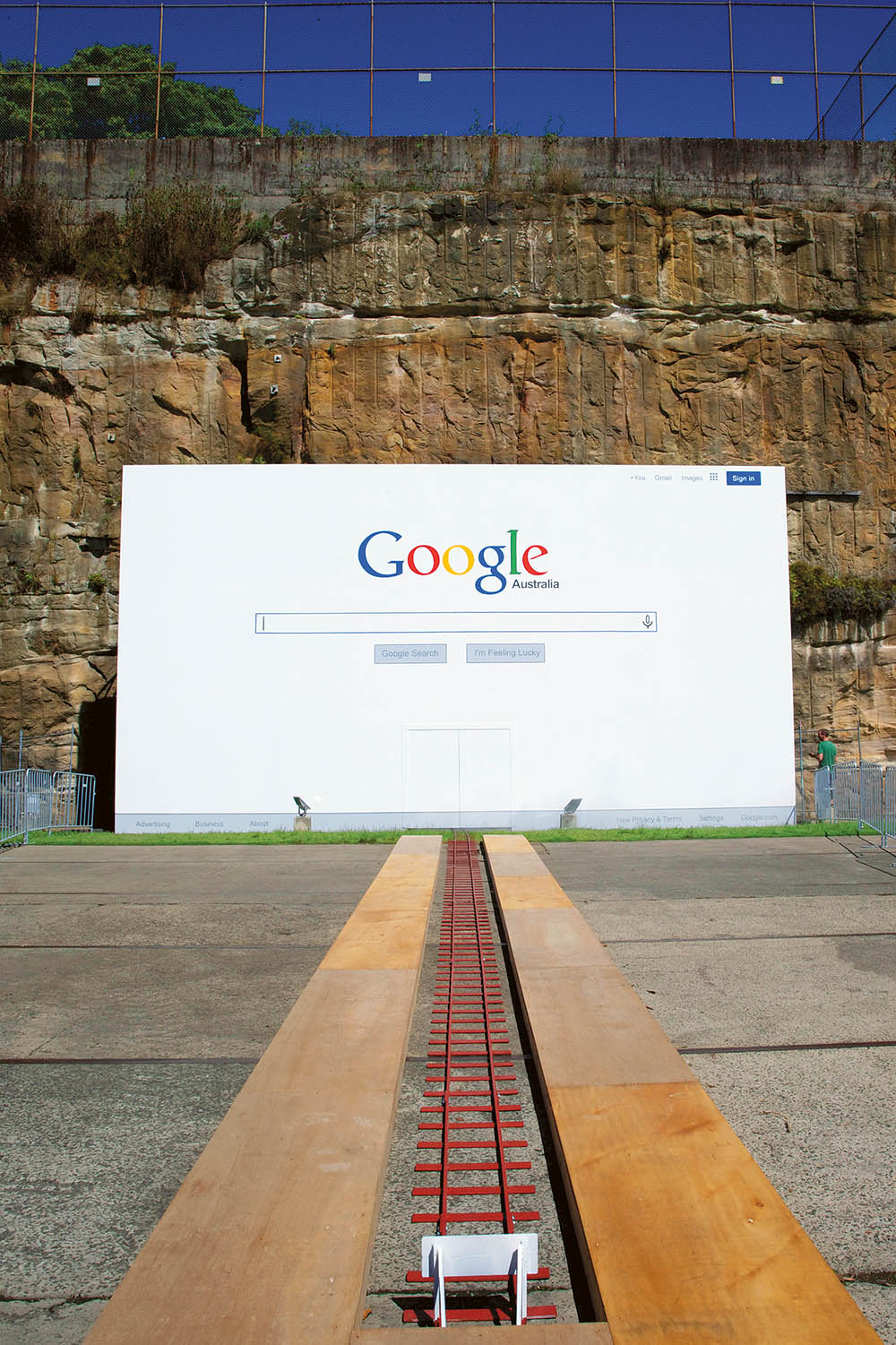

Engberg’s artistic directorship of the Sydney Biennale 2014, titled You Imagine What You Desire, saw her stage an exuberant and playful exhibition featuring work by 92 artists from across the globe who share her regard for the power of the imagination and the role of art as living philosophy. Rejecting a thematic approach, the Biennale was intended as an open system, allowing the viewer to assemble their own narratives based on interaction with the artworks and their own desires. The Biennale took place across white cubes and raw industrial spaces, including the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Artspace, Carriageworks and wild Cockatoo Island. The project almost ran aground when a sponsor was revealed to be a contractor for immigrant detention centres in Australia, the thorny relationship between art and its financing being thrown into stark relief and precipitating a walkout by many of the artists. Engberg was instrumental in the weathering of this storm, with many of the boycotters returning to participate after the Biennale’s chairman stood down.

How do you define your curatorial style?

I see my practice as being concerned with the three As: art, artists and audiences. I’ve put audiences into that equation because for me it’s very important that I acknowledge an attendance and engagement of thought in what we do. I do place art at the forefront, as my interest has always been to look at the primary producer and to take care of artistic history. If you don’t do that, there is a bit of a danger that in seeking audiences we get glib. You can make the error of thinking you have to dumb down and make everything spectacular and entertaining.

Can you explain the title of your Sydney Biennale, You Imagine What You Desire?

It comes from George Bernard Shaw. I never intended for it to be understood as a theme, I intended it to be an evocation. Invariably journalists think it’s a theme and try to unpick that, but I felt that Shaw’s comments—‘Imagination is the start of creativity’, ‘you imagine what you desire’, ‘you create what you will’—are about active philosophy, which is what art is. That, and the pursuit of the generally unobtainable. I was interested in the drive, what compels an artist to make art, and what compels an audience to seek art. I wanted to tie that active philosophy and desire in the artist’s mind with that of the audience, the artist bringing something imagined out of this desire, to an audience seeking things that they (perhaps unconsciously) feel they want.

In the essay in the catalogue I talk about the fact that there are all kinds of things that people are seeking when they come to a biennale. We’re all looking for antidotes to our condition of being. I suppose that’s a humanist proposition overall, and I’m unapologetically humanist. I see art as having a very important role in shaping and reflecting the kind of society that we desire, and that we hope for. The Biennale itself started to look at a whole host of things that one might imagine, so what you imagine for society is as much a political statement as it is a creative statement. What you imagine for yourself, and others, may be somewhat therapeutic and is done through symbolism and metaphor as it always has been done.

It was a broad evocation. Sydney is a big event, similar to Documenta. In that respect I think having a ‘theme’ is restricting and there is a danger you will repeat it and make it stale. So what I hoped to do was give many variations so the audience could find what they were looking for. The Biennale needed to be porous for an audience to find its way into it and I wanted to be generous enough that people could find their own connections. That’s the fun of it.

How did your concept for the Biennale play out among the different venues such as Cockatoo Island?

The building stock that you have to work with in Sydney is very different.You have some museum venues that have very low ceilings and you have to find some character for them. Cockatoo Island is very characterful, but it’s unkempt and feral and difficult to use. I decided to give them all personalities, which I thought would act as a trail, little pearls on a necklace that the public could pick up along the way. So I tended to use a psychogeographic approach and because of that I thought one of the defining concepts could be the elements. I’ve always been attracted to the poetic in the elemental, and it creates a strong set of symbols and metaphors in art practice, so I tried to create a unity within all the spaces with those ideas in mind and then those ideas filtered out through the venues as they moved through. Each had these connectors—following the water trajectory, for example.

How did the controversy around the Transfield sponsorship, who were revealed to be involved in immigrant detention centres in Australia, affect the Biennale?

I suppose the first thing was that it was a shock and a surprise to all of us inside the Biennale. It had an immediate effect on the morale of the team. Originally the artists’ concerns were against the government’s policy towards asylum seekers and the o shore detention process. But quite quickly, and unfortunately, attention was diverted away from the core issue of the policy.We all had great sympathy for the original cause, but as the agitation progressed it got less about that. Suddenly we were dealing with the prospect of the Biennale being tenuous. I had to do a lot of work to maintain the energy and morale. When the board made the extreme decision to separate away from Transfield, and the chair stepped down, all the boycott artists, bar two, came back. The press had become very agitated around the asylum/ sponsor issue, so the energy for the opening event was sadly rerouted. But three weeks into the Biennale people started to look at the art, and there was another change—the Biennale started to emerge.

I think the consequences rather than the circumstances of it are interesting. It gives the Biennale an excellent opportunity to evaluate and remodel itself; give consideration to how one does deal with the necessity to raise funds. You can’t be misaligned with the ethics of your core constituency— the artists. They are your primary sponsor, so if you are misaligned you have a problem.

The biennale model has come under fire in recent years. Do you think there is life left in the form yet?

Yes. I think it’s funny, this whole rhetoric around the problem with biennales. There is no problem with them. I’ve just seen four in the past three weeks, each different, showing different work, going for a different idea. They are events that come around every two years, shaped by diverse curatorial approaches. They generate a great deal of discussion and debate and excitement and they are a clearly visible event for a public looking to be attracted to contemporary art in a different way to museums and smaller enterprises. And I wonder who constructs this rhetoric. Nobody knows what a biennale should be, and that’s its strength. I prefer a chaotic version. The thing I worry about is when biennales start to look like a museum exhibition, then they lose the energy that a biennale can create.

What is the greatest challenge curating in Australia?

The greatest challenge remains distance. Freight is extremely costly and it limits what sort of work you can show. Because of the distance, one tends to think of Australia as having its own art world, and that can be a little solipsistic, at times diminishing practice instead of expanding it. This is why I have committed myself to bringing international work into Australia, so students and young artists coming through can see what their peers are doing and have some broader perspective on their own approach.

How has the contemporary art scene changed in Australia over the course of your career?

It has become more ambitious, certainly larger. We have a number of spaces for contemporary art. The thing that I think is missing, and this might be a funny thing for a contemporary curator to say, is that I think we have a shallow understanding of history, and I always worry that there is a tendency to concentrate on the contemporary, abandoning the historical. If you don’t look to the past then your contemporary work will look vapid.

This interview is excerpted from ‘The New Curator: Researcher, Commissioner, Keeper, Interpreter, Producer, Collaborator’ by Natasha Hoare, Coline Milliard et al (published by Laurence King Publishing).