The painter Danny Fox returns to Los Angeles from England to debut an intimate series of paintings and the project space-gallery of the artist Henry Taylor, his former neighbor and forever friend.

On South Los Angeles Street in downtown, piles of trash line the sidewalk of the commercial street, and colorful store signs hint at the life that awakens during business hours. Skid Row on one side, the flower district on the other. I wait outside a tall building for Danny Fox to come down and bring me up, thinking of works from the painter’s past where such streets and the people who populate them would materialize as symbols in his work.

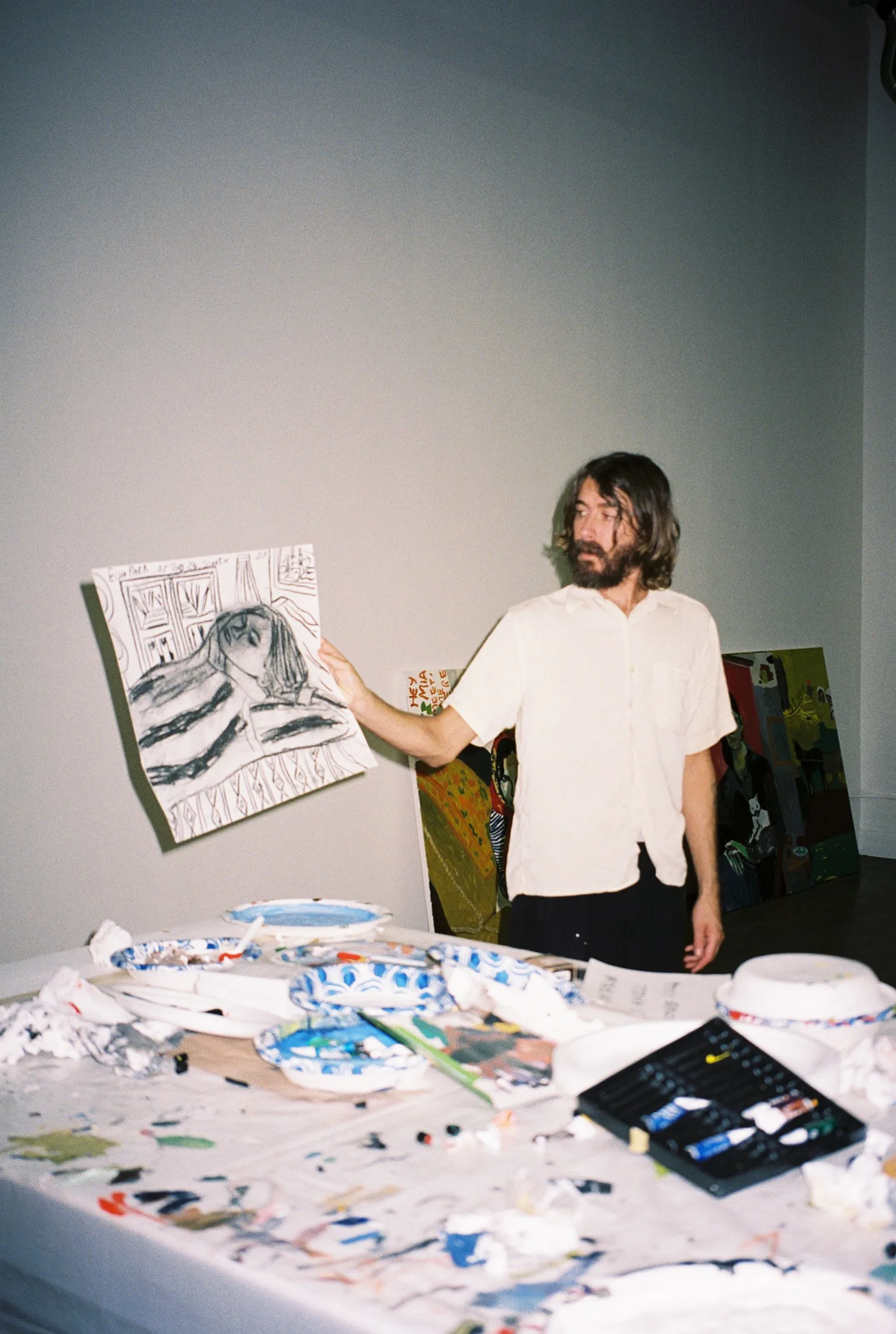

The painter swings the door open, wearing dress pants, a blazer, and a button down, with chin-length wavy light brown hair and wire-rimmed glasses. When he smiles, he gets a wild look in his eyes, and gold teeth glisten. The black outlines of a rose and a cross tattooed on his hand flutter into view as he gestures to his works.

In his studio, he is thoughtful and deliberate when he discusses his work, careful to find the right words, but he moves throughout the space with a certain swagger and a freedom. There is also a hint of rebelliousness, subdued at least for our conversation: We’re here to talk about art.

Fox is at ease surrounded by his paintings, some depictions of people in his life, some composites from his imagination, all made over the past two months while he’s been camping out indefinitely as he prepares for his show “The Rain It Raineth Every Day,” which opens tonight on a full supermoon at Henry Taylor’s project space-gallery and former studio, a 10 minute drive away in Chinatown.

We sit on sparse, black chairs across from each other. Behind him is a small mattress with pale pink sheets pushed up against the wall facing his works and framed by a stack of used books, a single spot to rest when he isn’t painting. At night, he likes to walk down the mostly empty city streets.

In one new work not in the show, a woman in a red headscarf lounges on cushions with the words “Hey Mia, meet me here” emblazoned on the top corner. “Everywhere she would go, she would write ‘Hey, meet me here’ to her best friend, in the dust on a car, in the sand on a beach,” he says, reflecting on the phrase and all the images it conveyed. Another painting has the name Norman written on it, its meaning in the spirit of many of Fox’s works: enigmatic on first glance and brimming with meaning upon explanation. “When I was making it I found out that a friend called Norman Hyams passed away. He was a good painter, a good man.” Fox likes to paint stories, and lately those closest to his heart are coming to the surface. “The writing is a part of the work, too,” he says.

“You know how they say everyone has a novel in them? I don’t think I have one,” he offers. “But I’ve read your writing,” I say. It’s descriptive, puts you there. “You could string it all together,” I suggest. “I mean, I’ve got stories in me, definitely,” he concedes. “I can see whole movies scene by scene, and I know how they look, and I know the dialogue. I would love to do it, but I just don’t,” he trails off… “I should do something with it. I mean, the book of studio notes is like this high now,” he extends his arms to their limit. “I always said that I would do something with that before I’m 40, which seemed so far away, and now I’m 38.” Then again, he adds, “That they’re not public—there’s something helpful about that to me.”

As he speaks, I scan his paintings lined against the walls. They appear almost like stills, suspended mid-action from a film. One work shows the side profile of a man walking along a dock. A dog approaches him, with a ball in its mouth. You can imagine that he will continue passing by, that he still has somewhere to go—or maybe he will stop and throw the ball. There’s life in it, possibility.

This work, among the others, have all been made since the artist first arrived some four weeks ago. It’s quieter here, he observes. “When I wake up there’s no wind, I finally feel like I can think… It’s very windy where I live, and it really gets to me. It kind of drives you a bit mad,” he says of his home in Cornwall, England. This is the first time Fox has been back in Los Angeles since he left during the pandemic. “In some ways, it’s like time stood still,” he continues. When the painter moved to LA in 2016, it was right after Trump became president for the first time.

Now we meet again, coincidentally on the day of the election results. “There was this same feeling of fear and uncertainty, which adds to the atmosphere of the place… No one knows what’s going to happen,” he says. “Maybe that’s in the whole world right now.” But inside his studio, there is a sense of harmony, partly because every painting was created with a limited palette of primary colors, a practical decision for traveling light.

Fox has all he needs here: a place to work, and a friend to snowball ideas off of. His initial trip to the city of angels was a vacation that turned into a four-year stay, after a fateful job loss and a studio in the same building as Taylor (and the same building we are in today). The two artists initially met a decade ago at a pub in London, and have since developed a close friendship.

“Sometimes someone would come to see me and then hear Henry across the walls, or the other way around. It would happen all the time,” he says with a laugh. “It felt like I had known him forever even when we had just met. Henry is my favorite living artist,” he reflects. “There’s a feeling as an artist that you’re always looking for, which is to be inspired. And when you get around it, it feels really good. You get energy from it.” Today as he prepares for the exhibition, he sleeps in a room at Taylor’s house, surrounded by seven of his paintings. It is a full circle moment of sorts.

The works on view at Chinatown Taylor’s were painted from Fox’s hometown: a misty, rural coastal county about 5 hours south of London, where the painter returned to during the pandemic. In the spring in England, he will have his first institutional show at the University of Plymouth.

In Fox’s mind, stories unfold ceaselessly: characters, vignettes, scenes told and untold, a novel packed with details that come out with more immediacy in paint than if he were to write them down—but he still does. And like all great writers and artists, everything is source material for the artist: the beautiful, the painful, the overlooked. The good, the bad, and the ugly. It has to be this way, and it has to have a story. And now, we are off to the gallery to address a story culled from the painter’s own life: the woman in the room. She appears three times out of the six total works (a pared down number that Fox and Taylor arrived at from an original 17 works). The paintings needed space to breathe. In two scenes, she is at the same table. Head resting in her arms. She was getting off medication, going through withdrawal, Fox shares.

In Self Pumpkin With Parasite, 2024, Fox, pen in hand, looks across the table—a new development where the artist himself appears in his work. “I would work during the day, and then we’d always meet around the family table at the end of the day,” he remembers. “She was going through withdrawals, so she would explain to me the discomfort she was in, and I would just sit with her. It is a pretty helpless feeling. Making work about it can ease that sense of helplessness.” For Fox, the devil is in the details—and what is left unsaid. When he made these paintings, it rained for 200 days straight.

In another painting, her eyes glance at Fox, tired and sorrowful yet determined. Vibrant colors are both jarring and offer a tinge of buoyancy to the heavy subject matter: a bright yellow wall, a blue sweater and green pants. A found image of an elderly couple against a red backdrop hovers in the background—Fox was thinking of stories she had shared about her grandparents. In front of her, a book is titled “The North”. The paintings were made in the aftermath, after she packed up everything that was hers and left. “Do you know where she is now?” I ask. “No.”

“Has she seen the works?”

“No, we don’t speak anymore.”

“When you were making them, were you thinking of her seeing them?”

“No, I wasn’t thinking of her seeing them, and if I’m honest, I don’t think she would want to see them.

“Too close to home?”

“Yeah…I don’t think she would be impressed or flattered that she was a subject of the paintings, but I do think she understands enough about art to understand that they had to be made. She knows that if you’re going to be around me then there’s going to be art made about whatever’s happening.”

Standing in the sparse room with the artist, it is clear that this is personal. These final moments from a relationship float isolated on the walls, charged with their own energies. Fox talks earnestly, aware that the nature of getting close means that those in his life will inevitably end up in his work. Is it about her? Yes, but also it is about the artist looking, his gaze tender, unflinching, and compulsive.

To paint is to confront life head on, Fox’s work seems to suggest. To reveal the things you may want to hide, to find beauty in darkness. To reconcile. “I’ve always wanted to go to a place where I can make it personal,” he says. “The more I work, the older I get, I feel like I am more able to depict that inner thing,” he trails off…”Fuck, I can’t say it right, but if I could I wouldn’t paint it.”

Written by Meka Boyle