Speaking with David Blandy during 2020’s Brent Biennial, I was struck by how oddly suitable his practice seemed to the moment we were living in. His work expands the imaginative possibilities of gaming and internet culture into what we clumsily distinguish as ‘the real world,’ but which, in 2020, was warped beyond recognition by the pandemic. Already unstable existential boundaries loosened yet further, bringing Blandy’s work—its escapist, futuristic impulses coupled with warm, fuzzy nostalgia and communitarianism—into new relevance.

Blandy worked with young people in Harlesden to imagine the area 8000 years from now, creating the post-Anthropocene, high fantasy world of The World After (originally commissioned by Focal Point Gallery and New Geographies in 2019) as a host landscape. “In many ways the project was a return to my childhood,” Blandy says. “I grew up just down the road from Harlesden and played a lot of playground games: imagining being different characters in fantasy environments.” The project reaches across divides which are at times invisible: digital, geographic, socioeconomic and imaginative, “trying to find new ways to form kin outside of the digital space.”

Would you like to start by telling us about The World After?

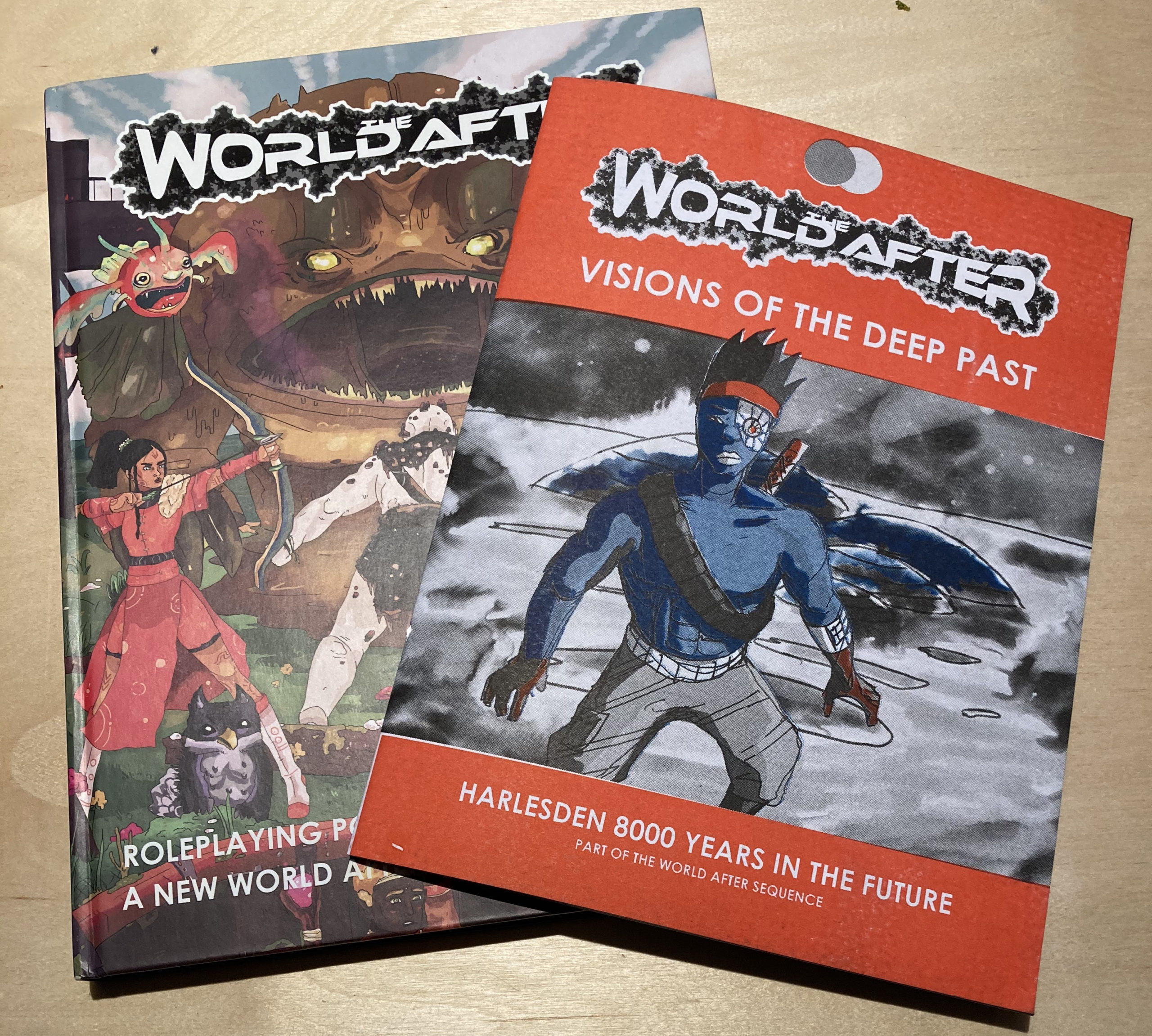

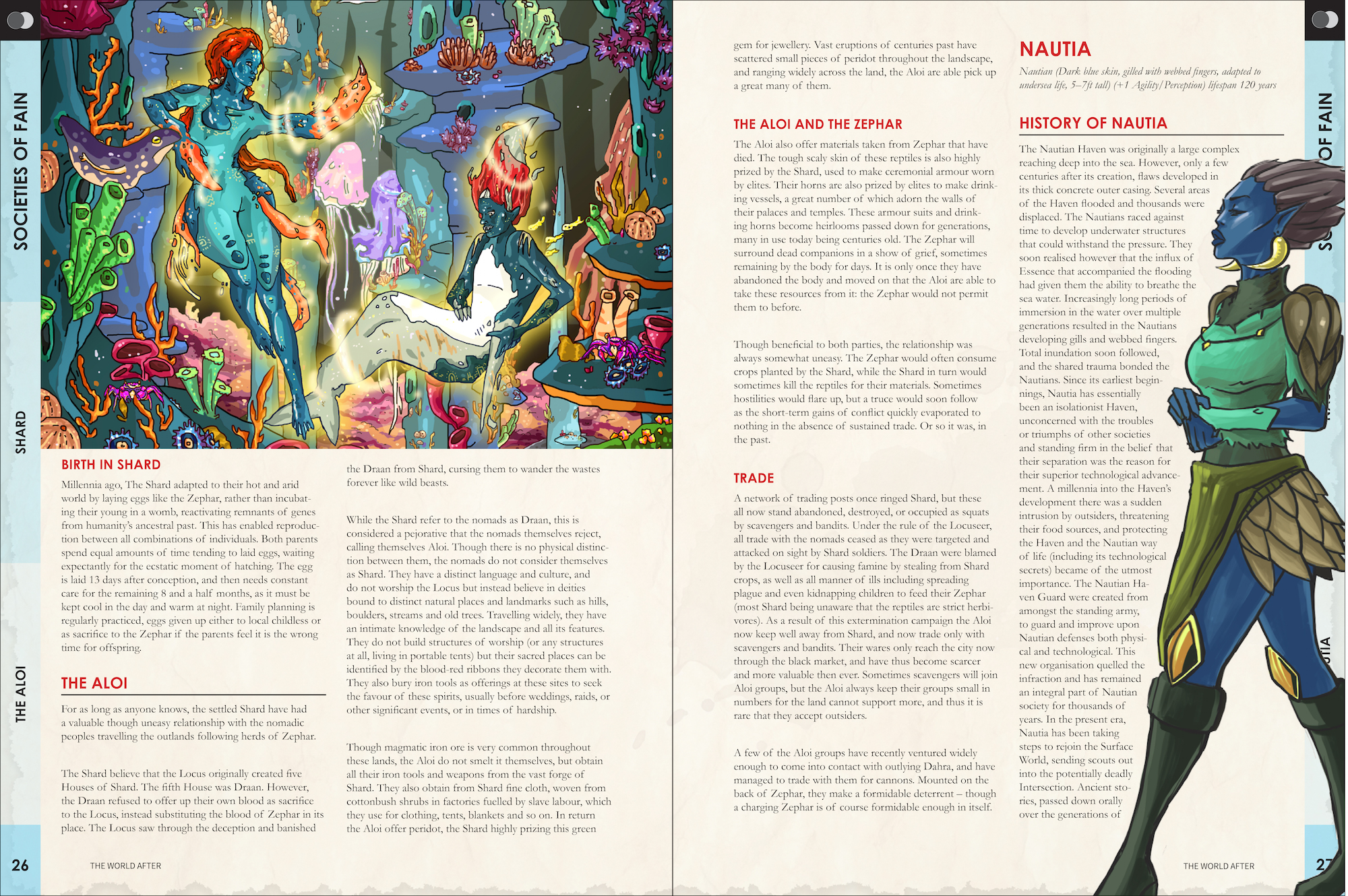

The World After is a project I’ve been doing for a few years, bringing together visions of a future after the climate cataclysm, where essentially a series of post-human societies are set up. I asked a couple of youth groups in Harlesden, Northwest London to respond to this idea. Both came up with ideas for different groups that would have been gestating underground for 8000 years before emerging onto the ‘present day’ of the fictional world (but our future)—seeing the Harlesden of now as a sort of deep past to be explored.

“The end of capitalism is pretty hard to envision, but a fantasy space as offered by a role-playing game gives a space to try”

The two groups were quite different. One was at an academy school that has a very strong arts provision, so they were drawing, brainstorming, designing these different societies: one based on beasts, one based on amphibious forms, one based on birds. They then imagined how those societies would be structured.

The World After Books, 2020. Courtesy the artist

The second is more of a loose group of local young people, and they were much more interested in really building the game through playing it. They created a society of cyborgs—they were interested in how one could order oneself to adapt to the environment through body hacking. We then used those characters to go on an adventure where they explored leaving their underground haven and making their way to the surface.

It was a chance to set a childhood realm in an environment that takes into account our current climate disaster while also trying to find new ways to form kin outside of the digital space. It’s a project that encourages personal interaction, something that’s very difficult right now in the time of the pandemic.

What expectations did you have about opening up your own ideas up to a community—and did the responses live up to these?

I always approach collaborative work with a thought that I’d be open to whatever ideas people come up with. Both institutions were very supportive in encouraging people to take part—and both groups came up with ideas that I hadn’t considered. They wanted it to be much more fantasy than I had expected—I thought it would be rooted in a more local urban reality. They were much more interested in making it escapist—but, at the same time, all the societies described had very rooted structures.

“Imagining the high street under layers of debris made the implications of climate change much more integrated into my known reality”

Groups I’ve worked with in the past have come up with utopian societies, but there was nothing like that here. I’m trying to encourage thinking through the lives of others and to form new, collaborative possibilities—but I like to honour the truth of what people come up with. That sets the scene for when these societies are played out in the games: they’re going from these strict hierarchies into finding something much more flexible in the game itself, where they have to cooperate with members of different societies.

What points of overlap did you see between their experience and yours when interacting with these teenagers? Did that geographical and social experience come out in the work?

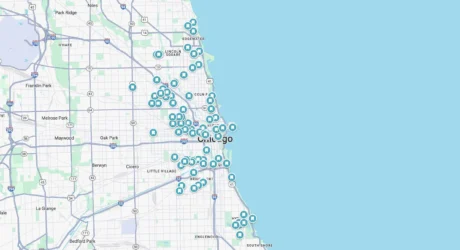

It certainly came out in my experience of making the work. There was something about the mapmaking of the local area: imagining the local area after 30 metres of sea rise, and thinking about a shoreline being near Kensal Green. Radically reinterpreting the landscape interacted with my memories in a much more visceral way than other projects where I haven’t known the place as well.

- Claire Barrett, photographs for The World After, 2019. Courtesy David Blandy

“It’s a project that encourages personal interaction, something that’s very difficult right now in the time of the pandemic”

It made it much more real to me, somehow. Imagining the high street under layers of debris and doing an archeological dig to find signs of the past made the implications of climate change much more integrated into my known reality. Previously it had been much more academic; now it felt a lot more personal.

Can you talk about how these ideas of futurity, the environment and extra-scientific possibility intersect with gaming and virtual realities in your wider work? Especially in A Lament for Power; Lost Eons; and The End of the World…

Throughout my work I’m trying to figure out how the self is constructed across spaces, through the visual, the narrative, the ludic and virtual. The World After (continuing at the moment through the project Lost Eons) is an active form of imagining different societal models, different ways of living. To paraphrase, the end of capitalism is pretty hard to envision, but a fantasy space as offered by a role-playing game (RPG) gives a space to try—both to imagine utopias but also dysfunctional and dystopian visions. Trying to mix Darwinian biology and the myths of Tolkienesque fantasy throws up a lot of interesting problems, but has also served to highlight the absurdity of conventions, both in how we allow ourselves to be controlled and also in the stories we tell.

The End of the World (2017) was a way of attempting to pinpoint grief across sites, from the geo-political grief brought about through the global rise in fascism, through to the virtual grief of the end of a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) world (Asheron’s Call), and the intense personal grief of the loss of a loved one. A Lament for Power (2020), a work made with Larry Achiampong, expanded on some of these ideas, while focusing on the exploitation of personal genetic material for corporate profit.

“The End of the World was a way of attempting to pinpoint grief”

Henrietta Lacks never consented to having her cells propagated, but they have now been grown so often in the laboratory that their collective weight is more than the Empire State Building. Technology may advance, but the ways that we interact are remarkably static: either collaborating or exploiting each other to alter our realities. Exploitation currently has the upper hand, but collective action seems to be gaining momentum. Building art, games and imagined worlds together is one way to keep resisting.

Within these same contexts, can you explain a bit about how you work with Larry [Achiampong] and how your respective practices complement each other?

Larry and I have worked together for the past seven years, building a practice together that runs alongside our solo work. Inevitably these two strands influence each other. We largely work remotely, keeping up an unfinished conversation across multiple platforms. I’m enjoying Discord right now with all my RPG groups, so I think I’ll try to tempt Larry onto that too. Our practices were remarkably similar before meeting, both looking at the self, race and identity as defined by popular culture, and we really bonded talking about video games, hip hop and London life.

“There is a particular combination of testimony, analysis and poetry that Larry and I create together”

As we got to know and trust each other, this really developed into thoughts about societal systems, and our place in the “Grid”—the intersection of our various selves. This led us to Frantz Fanon, his lost plays and a whole chapter of our work: the Finding Fanon Trilogy (2015-7). We’re now deep into our next long-term project, around how systemic racism and eugenic theory are embedded in our organisational systems, and there at the root of seemingly objective disciplines such as biology (Carl Linnaeus), statistics (Francis Galton), and archaeology (Flinders Petrie).

This series, Genetic Automata, has had two instalments so far, A Terrible Fiction (2019)—which examines the relationship between Darwin and his taxidermy tutor Edmonstone, a freed slave—and A Lament for Power (2020). We’re currently working on a third part around archaeology, looking at the correspondence between Petrie and W.E.B. Du Bois; and the racist assumptions underpinning Petrie’s science.

Language is at the heart of both our work, and I think that is what gives these films any power that they might have. There is a particular combination of testimony, analysis and poetry that we create together, which becomes something more when framed by the video, CGI and soundtracks that we make together. There’s always been a freedom to working collaboratively with Larry, a feeling that we’ll just try things out and see if it works. Working with Larry gave me the courage to be more experimental, more open and clear in the work, and I hope being around what I do has helped Larry’s work too.