In 1935, the activist and historian WEB Du Bois published the essay Black Reconstruction in America, a mammoth achievement outlining the role played by African Americans in rebuilding the United States after the Civil War. Foundational American history, it vividly argued, could not be understood without acknowledging African Americans. In 1976, the artist David Driskell set himself a similarly ambitious task – to tell the story of 200 years of American art history through the work of Black artists.

Two Centuries of Black American Art changed the course of US art and art historical study. Mounted at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, it introduced visitors to African American art dating from 1750-1950, much by artists who had never been exhibited before. Two Centuries demonstrated that they were not just bit-parts in the wider narrative of American art history, but in Driskell’s words, “the backbone” of culture.

“Driskell’s art moved between abstraction, symbolism and figuration, its power in its versatility”

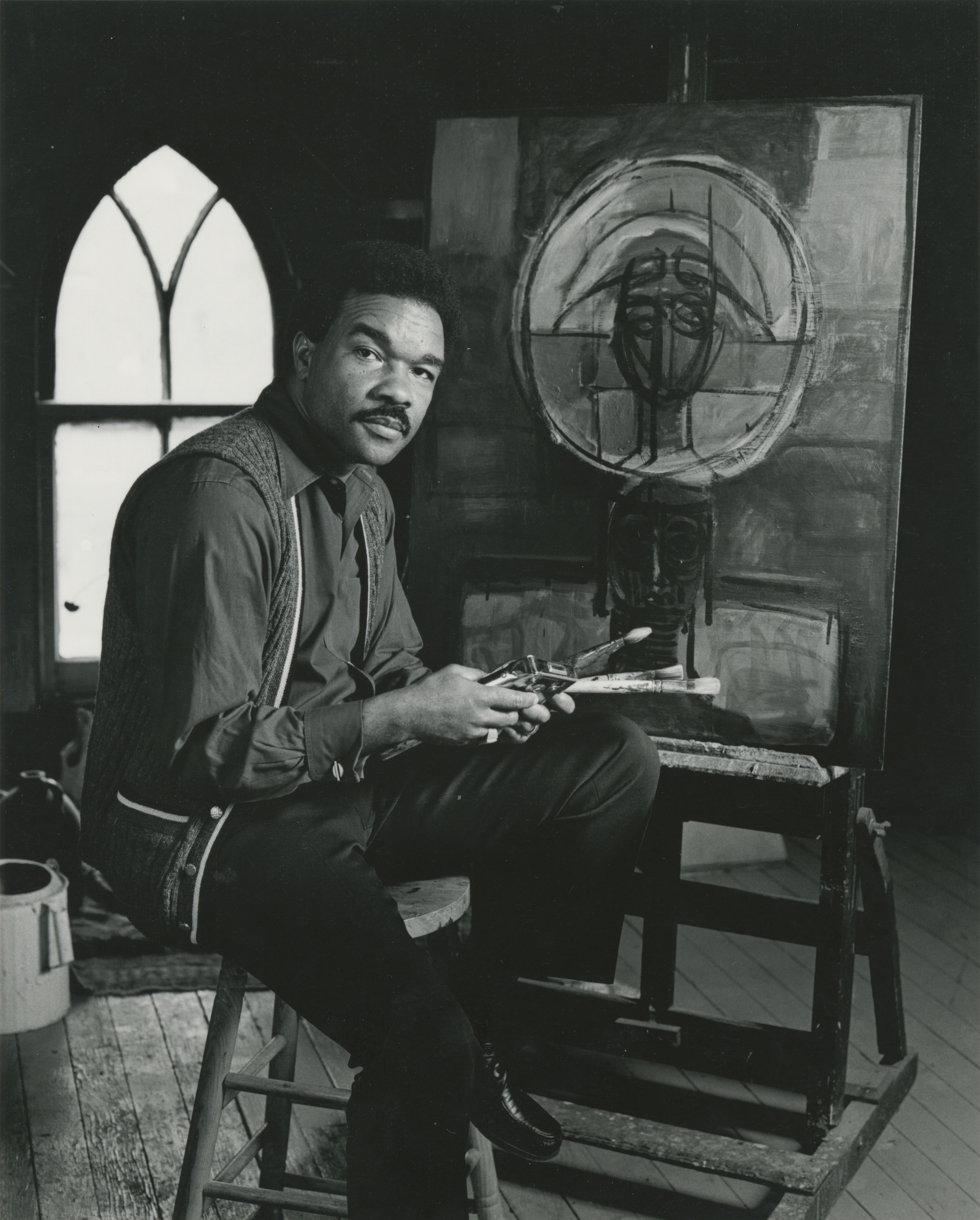

Earlier this year, HBO released In the Absence of Light, a documentary about Two Centuries featuring tributes from artists and curators including Kerry James Marshall, Thelma Golden, Carrie Mae Weems, Amy Sherald, Betye Saar and Theaster Gates. The exhibition alone is enough to secure Driskell’s place in American art history, but besides his work as a curator and scholar, or perhaps woven into his work as a curator and scholar, was his work as an artist too. It remains, however, the least well-known side of his legacy.

Redressing this is David Driskell: Icons of Nature and History (Rizzoli), published to coincide with a touring show of Driskell’s work curated by Julie McGee, and co-organised by the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, and the Portland Museum of Art, Maine, with support from The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. All three institutions were special to Driskell, who lived in Maine and Washington DC, and visited the High Museum as a young academic in Alabama, permitted to enter the gallery on ‘coloured only’ days (Driskell would return triumphantly to the High in 1977 when Two Centuries toured there). Sadly this celebration of his art arrives too late for him to enjoy it: Driskell died from coronavirus in April 2020, aged 88, while the show was still being shaped.

“Art in Driskell’s hands is an instrument of liberation, and exultance, and joy”

Driskell’s death gives this book poignant weight. Gathering scholarly criticism and personal reflections from friends and peers, the scale of his loss is apparent from the start. As Mark Bessire, director of the Portland Museum of Art writes in his introduction, “as we prepare the final touches to this extraordinary catalogue, my colleagues and I are in a perpetually fresh state of mourning. It did not have to be this way.”

Antique Chair, 1975. © Estate of David C Driskell, courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York

Solace is provided by the work Driskell left behind, of dancing angels and explosions of colour, open faces, towering pines, and round glowing suns. Driskell was a deeply spiritual man, the son of a Reverend, who synthesised his Christian faith with African and African-American traditions and philosophies. In his art, there is an ever-present sense of the divine: its belief in grace and goodness gives the work its distinct charge.

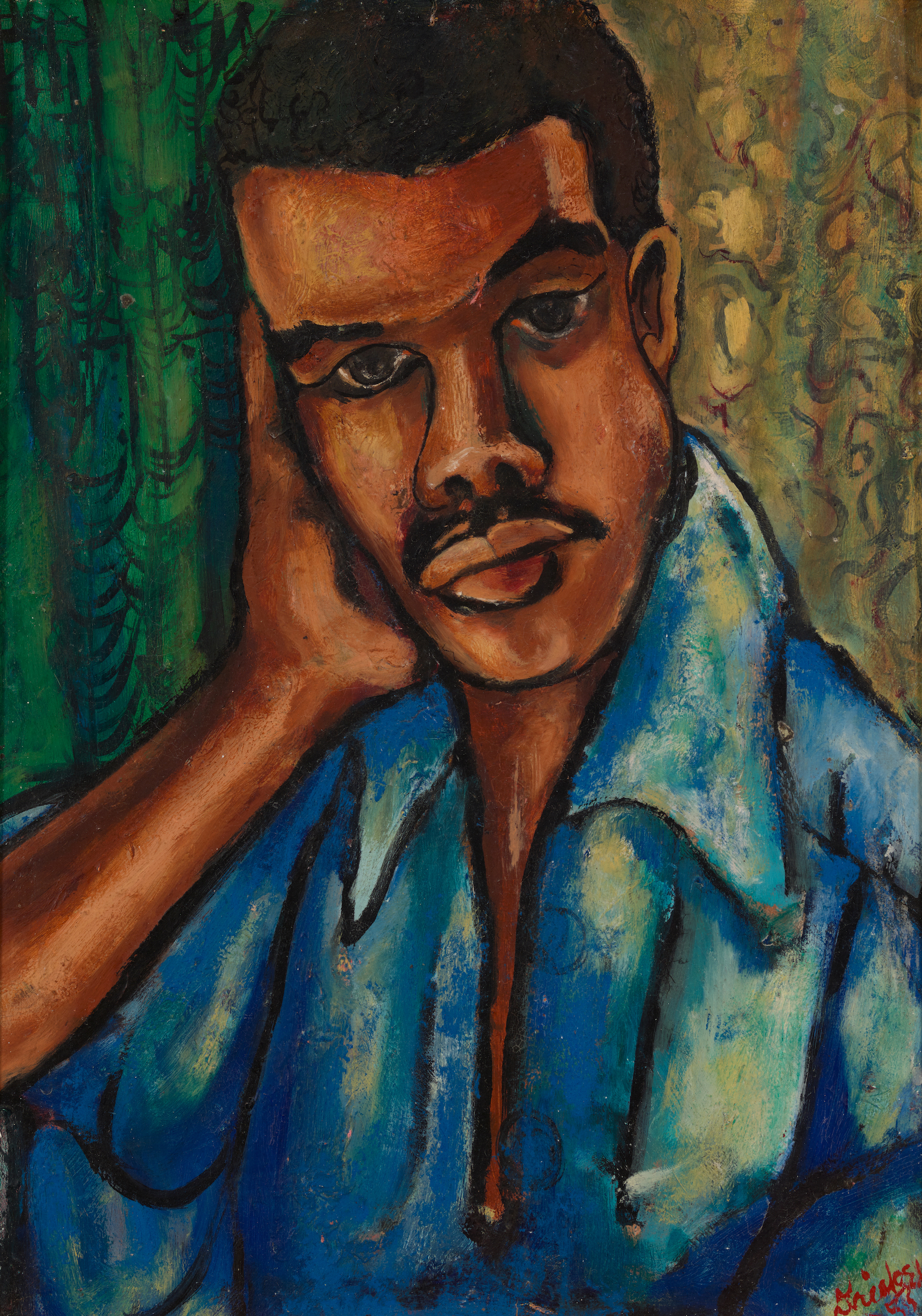

The book charts seven decades, leading with his canvases. In works such as Jazz Singer (Lady of Leisure) (1974), you witness a man engrossed in the possibilities of painting and pictorial representation, with its ability to be both familiar and foreign, to contain multitudes. In this collaged canvas, the woman’s face is split vertically (a feature of a number of his portraits and self-portraits) as if moving between states within the picture’s static plane. Her body is bristling, piecemeal, becoming.

“If exposing patterns of exclusion became his guiding mantra as a curator, then his raison d’etre as an artist was perfectly aligned”

Driskell once noted, “I am the quilter that my mother was. I am the builder, the gardener, and farmer that my father was. In my biblical subjects, I am the preacher my father and grandfather were. I am a sophisticated country bumpkin.” He saw no conflict in being all these things at once, and nor did his art, which moved between abstraction, symbolism and figuration, its power in its versatility.

Driskell’s art is singularly hard to pin down. His paintings are infused with influences from Southern folk traditions and Black Christian iconography to modernist experiments with geometry and space, and the formal clarity of West African sculpture. His heartbreaking pieta-like tribute to Emmett Till, Behold Thy Son (1956), is a rare example of his work being straightforward in either message or description.

“I make art to free myself,” Driskell said, “to give a new dimension to life, and hopefully other people’s lives, through this personal act of freedom I put on canvas”. Art in Driskell’s hands is an instrument of liberation, and exultance, and joy. If exposing patterns of exclusion became his guiding mantra as a curator, then his raison d’etre as an artist was perfectly aligned. His is an art of amalgamation, fullness, inclusivity. Within it, there is room for all.

David Driskell: Icons of Nature and History

Published by Rizzoli International Publications, 9 February 2021

VISIT WEBSITE