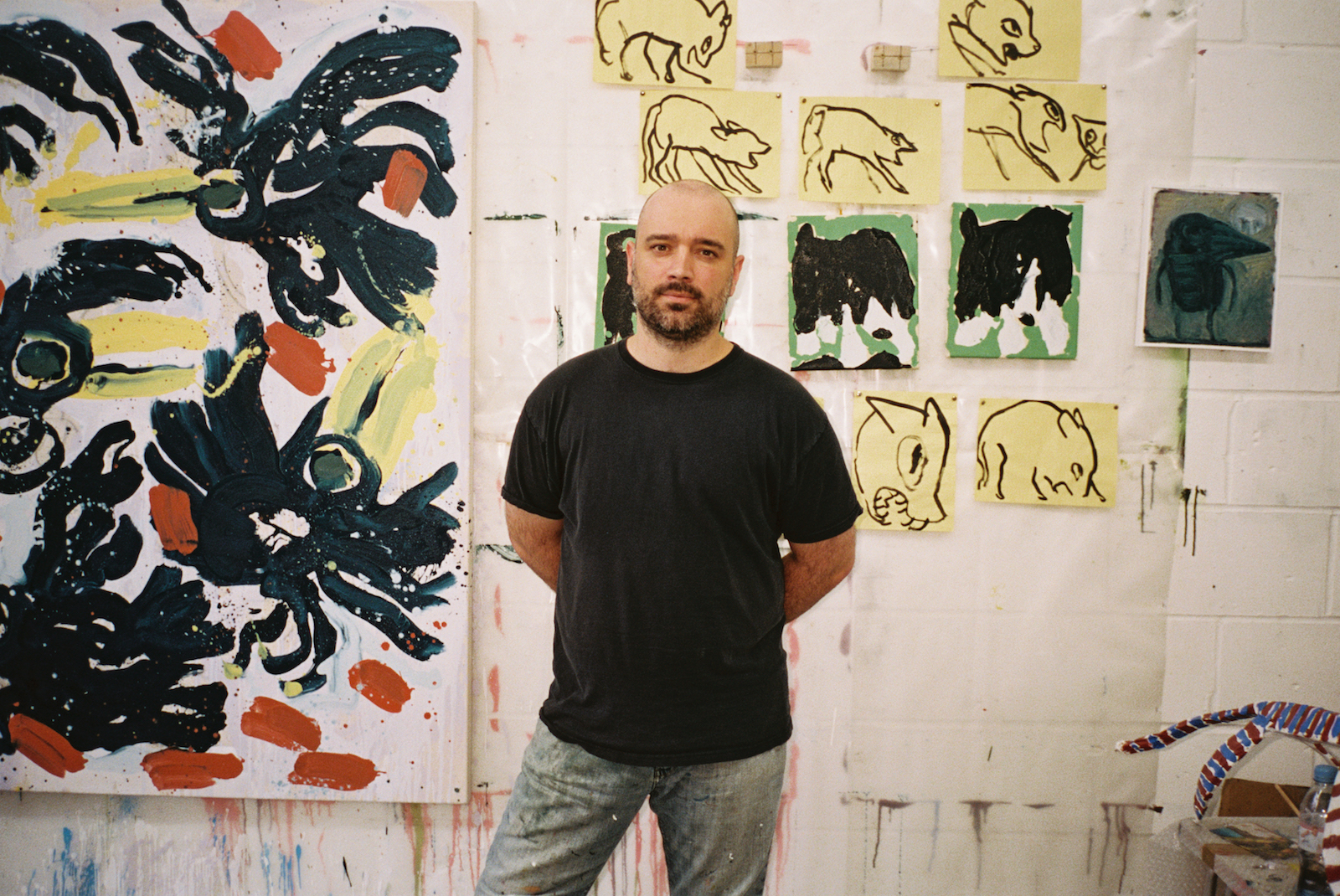

David Surman paints animals. David Surman paints animals in pretty colours, with attractive fluid lines. But there is more to this than pleasing the eye: animals in Surman’s work have a kind of sacred, mystical presence. They are part of our world, but also often parallel to our lives as humans. His attempts to capture their form and movement through the human hand prove how persistently ego-centric we are as creatures, in the face of animals who aren’t caught up in post-internet identity angst (a world that Surman, who grew up on the internet in the 1990s, is all too familiar with). As we launch our environment-themed winter issue of Elephant today, we ask Surman how his work ruminates on the way humans project their experiences onto animals, and how recent climate activism is changing our perception of our place in the world.

The title of one of your recent exhibitions was Painting for the Cat Dimension. What does that entail?

I’m very conscious of the world I’m living in, the state of the environment, technology, how language and identity is constantly changing. When I was a kid in the 1990s I spent a lot of time online. I lived in rural Scotland and used the early internet to find queer culture, art, music. Images of cats are synonymous with this early internet, people would say “the internet is made of cats”. I made a series of paintings of cats, the same underlying motif of a mother cat and two kittens. Each painting deliberately pushes a different stylistic idea. The “cat dimension” is the post-internet world of painting for me. It’s a place where I try out different identities. In that show, I’m using painting to call into question the identity of the young painter, that struggle to find an identity that happened through early internet culture. People observed that the cats are quite like Cheshire cats, and also made the comparison to Louis Wain’s work. I was quite happy with these comparisons, Wain was a visionary artist, and the Cheshire cat is a wonderful trickster figure.

Why do you enjoy painting animals, and are there particular animals you return to, and why?

I’m motivated to paint things I want to see, and it’s an absolutely visual experience for me. There is something sensational and thrilling in creating an image of an animal like a cockatoo or a crow on a large scale, without narrative trappings. I paint animals because I’m interested in their vitality, they really are the living world and I want simply to offer that for consideration. I am absolutely interested in people, but I find them tremendously complex. It’s an uncanny thing that by painting animals with a certain vitality you can say things both about the animal world and the world of people. The eye is very important to me, it is something quite remarkable to be looked at by an animal. John Berger said, “the eyes of an animal when they consider a man are attentive and wary. The same animal may well look at other species in the same way. He does not reserve a special look for man.” This is something quite special I think. Painting animals looking at us, in those eyes we are all rendered equal.

To answer your question about particular animals, I would say inevitably yes, there are certain animals I am drawn to. I tend to draw very universal animals, the kind of animals you might find in a children’s story. Having said that the more I paint certain animals they become motifs, and certain ideas start to bond to them. For example, I’ve painted horses alongside the words “She Knows” for some time now. These horses become emblematic of a kind of cautious, powerful female knowledge that augurs future problems. For example climate change.

It’s hard to paint animals from life. How do you do it?

I don’t explicitly work from photographs, I draw every animal from imagination and memory. But photographs are absolutely part of my process since we live and think through photography especially now in the digital era. I am always metabolising images of the things I like to look at and make art about, animal forms, historical painting and so on. Sometimes a certain thing will be a strong stimulation to make work; my cat paintings from 2017 were triggered by a Japanese statuette that I saw in an old auction house catalogue. Though I work with pure invention I’m open to visual ideas coming from anywhere.

Can you tell me about your exhibition, What Spirit Is This? earlier this year?

My gallerist Sim Smith had asked me to curate the inaugural show in her new space in Camberwell. This was, of course, a huge honour and I wanted to really put together an exhibition that posed a kind of open question about the state of painting at the present time. Digital painting cultures like that found on Instagram have had a transformative effect on painters and painting, we’re all suddenly so much more conscious of an entire world of connected artists offering a particular view into their work. Though I think artists like to think they’re free to use these tools without being affected, the compulsion to post and share and do a certain amount of figuring out in public has a tremendous effect.

Nonetheless, the basic impulses of art, to make, to transform materials, remain the same. The title of the show comes from a Kate Bush lyric, her song Misty on the 50 World for Snow album. I’m a big Kate Bush fan, she’s very visual in her songwriting. In this particular song she tells the story of a snowman who comes to visit a woman as a supernatural lover. She makes the snowman and then has this ‘encounter’ with it. I think this is the enduring appeal of painting, to make a thing that you want to see in the world, which forms the basis of an encounter, a sensation expressed through a material. The artists in the show were all individually important to me for their ability to convey powerful material sensations. They are all artists who are thinking through their materials without being bogged down by convention or style. It was a very uplifting and engaging show and I am very proud to have been able to bring together the artist’s work.

Do you think there’s a tendency to think that paintings of the natural world are somehow twee, decorative, or not intellectually serious?

I tend to think about art from an anthropological point of view, and your question brings to mind how every pre-industrial culture on the planet has a decorative tradition where the animal body would be used to convey many different ideas. It’s a matter of fact that as human society has advanced technologically and mass production now furnishes our lives we no longer have animal and plant forms adorning our spaces, clothes and objects with the same consistency. But I have a strong feeling that, in recent years, there has been a shift in our collective consciousness, caused by the climate emergency and figures like Greta Thurnberg.

We are now more and more conscious of the gap—what I refer to as the empathy gap—that exists between ourselves and the living world. We know we are too collectively alienated from the world, and that we need to close this gap, and make sacrifices to our way of life to do so. Though I don’t consider myself an overtly political artist I do think that I make work that addresses this gap, and that the art world is waking up to the non-human, animals, art that speaks to this necessity of re-engagement. I am a painter who is very conscious of art history and my works are made in a deliberate and calculated way. At the same time, I feel the necessity to direct the energies of paintings into this somewhat innocent project, to show animals in all their vitality as part of our changing consciousness.