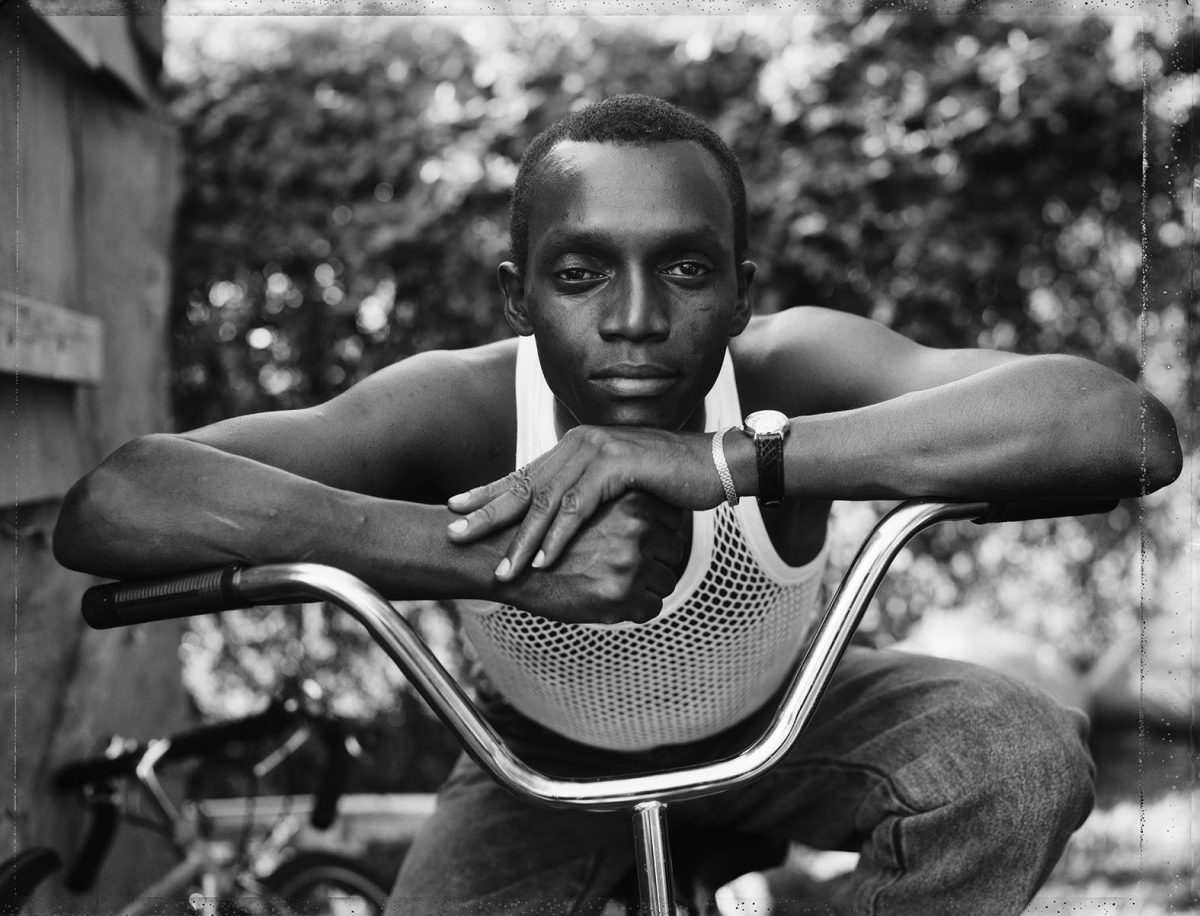

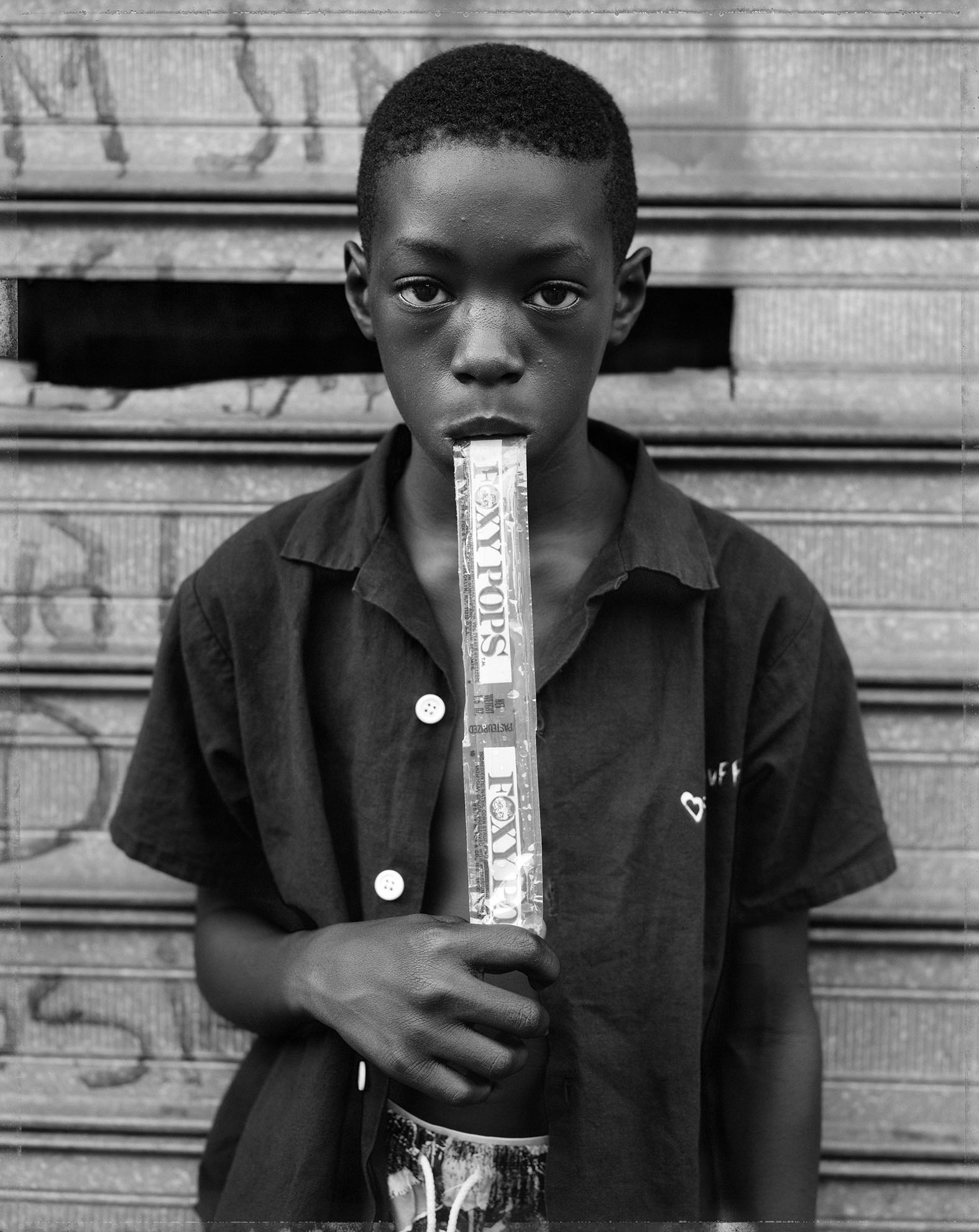

In Street Portraits, a select few of Dawoud Bey’s subjects are named, but most go by ‘A Man’ or ‘A Woman’, before their pose, clothing or recent activity is listed to complete their portrait title: A Man on the Way to the Cleaners; A Girl Coming from the Store; A Boy Wearing a Star Wars Shirt. Simply described but richly rendered, these are the chosen characters of Bey’s America between 1988 and 1991. The majority are shot in Brooklyn or Rochester, New York, with a few exceptions as the photographer ventured down to Washington, DC. All are Black, and while they remain anonymous, they are unified by a sense of community created by the sociopolitical reality of their times.

As an essay by writer Greg Tate reminds readers, the work in this photobook coincided with the second presidential term of Ronald Reagan, “commonly referred to as ‘the crack era’ and ‘the golden age of hip hop’” by Black contemporaries. The series epitomises Bey’s shift from 33mm film to large-format cameras, using Polaroid for finer detail and to provide an instant preview for his sitters. Subjects look deep into the camera, their sense of trust and directness lifting them above the documentary genre into something more quietly stylised and profound. Two players in a marching band stand idle in uniform; men and women lean on Brooklyn’s iron gates and stairways. Each seems to carry a story, as if the images should be accompanied by first-person testimony as a coda.

But Bey’s method is resolute, telling us that what we see is more than enough. The closeness of each shot adds significance to the subjects’ clothing, alongside other details enclosed by their silhouettes. A Nike cap, Georgetown bomber and UNLV Rebels T-shirt cut through the otherwise wordless studies of urban life, while hands sit alternately in pockets or placed in assured poses. His preference for single-person shots affirms a belief that a moment in life, and simultaneously, a past and unknown future, can be captured with a single click.

Bey was born in New York City in 1953, growing up in Queens at the height of the civil rights movement. Involved in activism from an early age as a member of the Black Panther Party, he has continued to return to this fraught period in his work. Birmingham: Four Girls and Two Boys in 2014 saw the artist replot the lives of those killed at the 1963 bombing of a Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama using substitutive portraiture. The series featured citizens of contemporary Birmingham: children the same age as those killed by the KKK attack, and local elders, each the age the children would have reached had they survived until 2014.

Street Portraits does not memorialise Black trauma in the same manner, but it still exudes an acknowledgement and solidarity with the ongoing struggles of African American life. Bey’s work “makes me think about the times I’ve walked down the street feeling inconsequential or even invisible, until I pass another Black person who holds my gaze long enough for us to exchange a nod”, poet Hanif Abdurraqib wrote last month. “Those moments of acknowledgement snap me back to fullness.” Thousands more now have the chance to sample this affinity as Bey’s major retrospective, An American Project, shows at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art this summer. “My American Project is that piece of the American fabric that is not always engaged or amplified in the great American narrative,” Bey said recently.

After inheriting a camera from his godfather in 1968, Bey’s attention turned to Harlem, a neighbourhood whose people, communities and social currents serve as a major preoccupation of his portraiture. After training as a jazz percussionist, Bey’s debut exhibition, Harlem USA at the Studio Museum in 1979 presented 25 small black and white images of residents, from diner staff to dressed-up women scanning the streets while leaning on a police roadblock. He would return to the district for Harlem Redux (2014-17), this time attuned to the gentrification which had so transformed his original source material.

Tate offers a brief history of image-making of African Americans, beginning with its short-lived origins as a justifying tool for white supremacist pseudoscience. This co-opting of Black personhood motivated thinkers like Frederick Douglass to later consider images of African Americans as opportunities for subject-creation. But Tate reminds us that denigrating depictions continued into the 20th century, embedded into American institutions like Hollywood, before Harlem Renaissance photo studios enabled artists like James Van Der Zee (and later, Gordon Parks and Roy DeCarava, who all influenced Bey) to inscribe the Black experience in visual terms.

It is this lineage to which Bey’s work belongs. Earlier this year, he explained the importance of the subjects’ hands to his work: “They are expressive… part of each of our idiosyncratic, expressive vocabulary,” he said. In his own hands, generations of sitters—their faces, fears and stories—are safe.