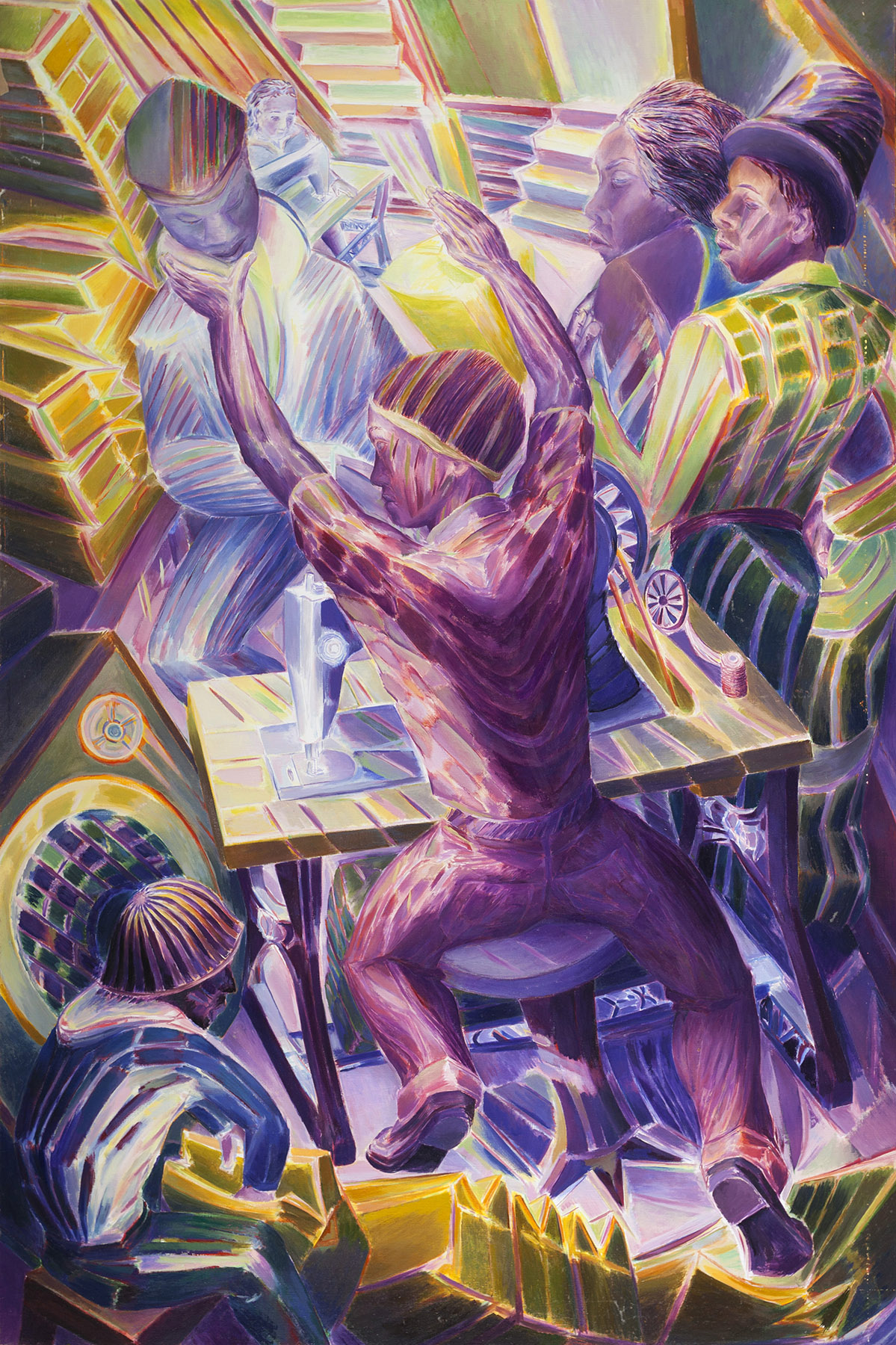

“I go drawing at night and during the day I paint at home,” the Granada-born British artist Denzil Forrester told Benjamin Zephaniah in a clip from a nineties BBC programme. It’s projected onto a wall of his retrospective, From Trench Town to Porthtowan at the Jackson Foundation in Cornwall’s St Just, which has been put together by Peter Doig and White Columns director Matthew Higgs. The clip describes how, throughout the eighties, Forrester would depict the east London dub scene that sprang up around such legendary DJs as Jah Shaka. In a 1983 oil which takes his name, Shaka is enshrined behind his sound system. Though it is a document of a very specific time and place, it could have easily, with its near-cubist arrangement of colour, have been painted in 1910s Paris by the likes of Robert Delaunay. And for Doig and Higgs, Forrester’s relatively unsung work is up there with the greats.

“I couldn’t go to a West End club,” he says almost thirty years after that clip was filmed. “I’d get kicked out for bringing my charcoal and pencils.” At the start he was treated sceptically, sketching as the rest danced. People would quite naturally wonder why he was watching them, let alone drawing them, and ask about it. But eventually he was accepted.

Speaking about his chosen subject matter, he tells me, “It came to me about the end of seventy-nine. I would have finished Central School of Art [Now Central St Martins]. I used to do landscape and models, but I needed something more to do with the place I was living. A lot of young people had house parties with two-speaker sound systems. My younger brothers used to do funny drawings of people at nightclubs. I started looking at what was happening in my community.

Having taught drawing for much of his career, he has only just retired to Cornwall, where the beaches remind him of the Caribbean ones he loved as a child. His mother came from Grenada to Stoke Newington when Forrester was three, leaving him in the care of a school teacher and her family. Was this for the opportunities the new area might present? “No, she had to get away from my dad. He couldn’t keep his hands off her. So, her sister sent her to London.” Then his mother, having not seen him since, sent for him in 1967 when he was eleven, towards the end of a period that now broadly qualifies him as a member of the Windrush generation. How does he feel about the recent scandal? “It’s disgusting. The people who are being squeezed are the people who have never left the country. They stay, they work, they get a bit older and want to see other places, then find they can’t come back. It’s horrible.”

Forrester’s best work has often been political. Death Walk, from 1983, shows the brutality done to Winston Rose, who lived in the same house as Forrester growing up, and who died in police custody in 1981. In a sketch, officers in a police van all sit with their feet on his body, which the artist says is how a social worker found them. In many respects the situation chimes with today: we are experiencing the rise of a new popular far-right ideology similar to that which stoked the National Front throughout the seventies and eighties. The Black Lives Matter movement in the US has shown that what happened to Winston Rose is still happening in some quarters today. Will Forrester make work that responds to the current political moment? “I’m not sure, because a lot of the stuff I was doing was because I knew Winston.”

He once tried to paint in response to the 1977 death in police custody of Bantu Stephen Biko, the Black Consciousness Movement activist in South Africa. “But it didn’t work. It has to affect me personally, then it comes from the right place.”

Why aren’t we seeing Forrester’s work in museums? The answer could be that he was marginalized for all sorts of reasons. He was not only describing what was politically volatile, but describing it in a way that wasn’t fashionable. Though Eric Fischl’s narrative figurative painting was popular across the Atlantic, it took him a while to get noticed, and it took Peter Doig—who, eleven years ago, became the world’s most expensive European painter—longer still, back in the UK.

“Some of Forrester’s very best club scenes have been painted in Truro over the last couple of years”

Looking at Forrester and Doig, one understands the kinship and mutual regard between the two artists. Not going into the similarities regarding their use of colour—which could make for a thesis in itself—both have a focus on painting of place, constructed from memories of home or a feeling of home, regardless of where in the world that is. Some of Forrester’s very best club scenes have been painted in Truro over the last couple of years, such as 2018’s Duppy Deh, in which light from a mirror ball makes shards of blue across the walls and the undetailed faces the dancers.

“I think the worlds of music and literature were much more able to deal with the kind of content that Denzil had in his work,” said Doig. “But with painting, the powers that be, the public, and the types of exhibitions that were being made, an artist like Denzil wasn’t really getting a look in. When you look back at it you think, ‘Why?’” He mentions The New Spirit in Painting, an influential 1981 Royal Academy exhibition. “Denzil’s a bit too young for that, but you can easily see him in it. If you put his paintings in that show they’d look like some of the strongest: the ones that haven’t aged or dated.”

“I think there will be a corrective where Denzil’s name and his work is introduced into the art historical narrative”

There is something about his use of colour and gesture that reminds me of Marc Chagall. When I asked Doig what canonical masters he saw in Forrester’s work, he mentioned Veronese alongside Stanley Spencer, Max Beckmann and Jorg Immendorff. You certainly get the same sort of grandness of vision, exploration of colour and perfection of composition on a huge scale. In Stitch Up, which recalls how his family sewed bags in their Stoke Newington home, there’s a sense of the huge work dragging your eye out in a diagonal into the corner as one of his family members goes up some stairs, which are almost distorted.

Matthew Higgs, who has curated the show with Doig, spent the nineties championing artists working outside of the Saatchi-endorsed YBA scene, and hopes the powers that be will change their minds. “Within the history of British painting of the post-war era, I think there will be a corrective where Denzil’s name and his work is introduced into the art historical narrative.”

But it already feels like there is a change happening. Last year Doig acquired one of Forrester’s most well-known works, Three Wicked Men, for Tate. And the show’s opening itself felt like a gathering of the powers that be. Nicholas Serota was there in sandals. Alex Farquharson of Tate Britain, too. But because Forrester never crested the wave that made American narrative painters of his day so hot, so many of his works have remained in his possession. Huge canvases from throughout his career can be displayed side by side in a stunning flurry. Something that Higgs says is present on every wall: a quality of “present tense-ness. Even if you’re looking at a painting from 1983, it resonates now.”