Pareidolia is the human tendency to see recognizable shapes and patterns in random places, and the most common form is seeing human faces and bodies where there are none, whether that be the face of Jesus in a piece of burnt toast, or Elvis’s famous outline in the clouds.

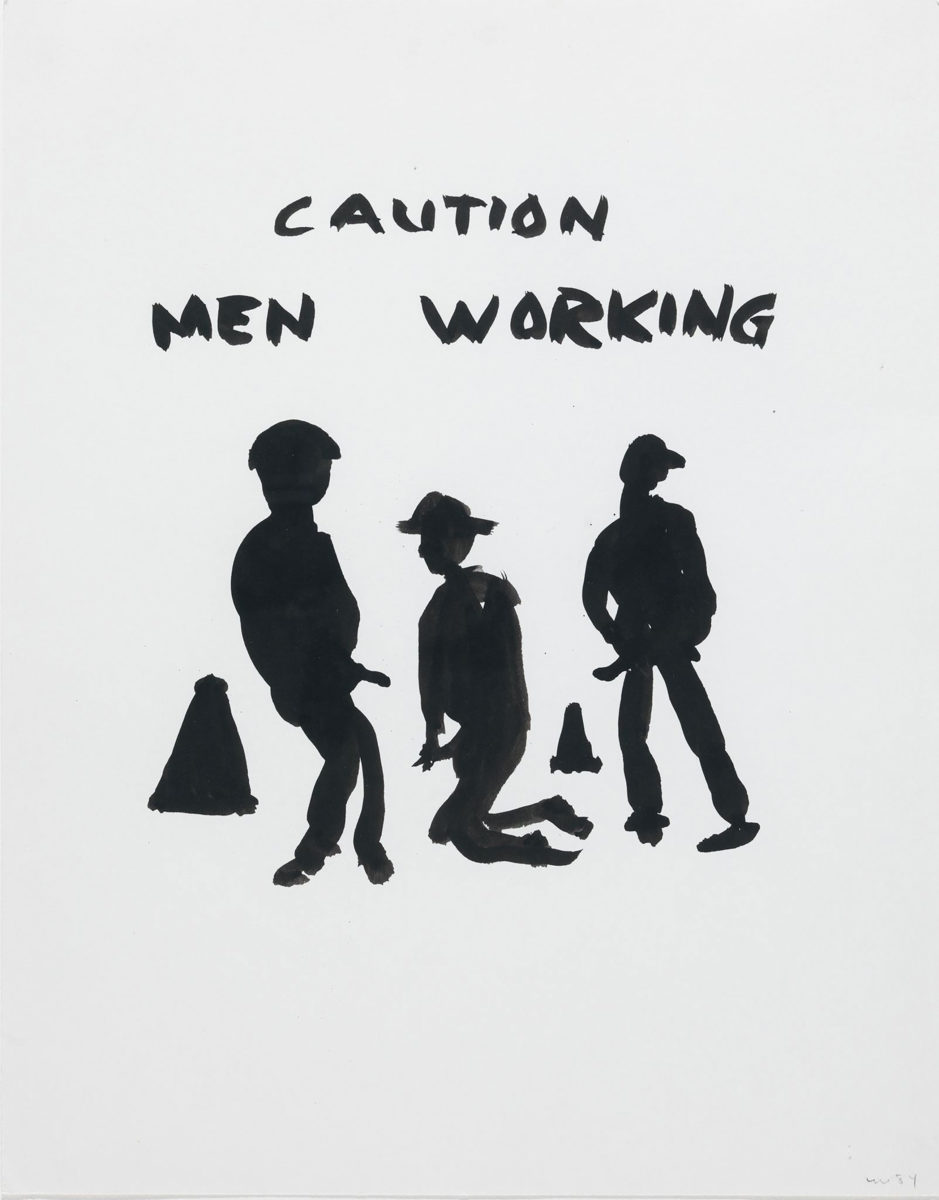

However, if you keep seeing faces and bodies at Artissima Art Fair this year, it’s not just your imagination playing tricks on you. The theme is Desire and Censorship, and this means round edges and suggestive drips, bright scarlets against dusky obscured blacks, and bodies, bodies, bodies.

“Desire springs from the relationship between the body and society”

Artissima 2019 features seven sections, some of which have been curated by the fair’s committee and others by teams of international curators. Known for its celebration of upcoming and experimental art, several of the Art Fair’s sections will revolve around this concern with experimentation and emerging talent, while others will feature artists sponsored by more established galleries, with room for dialogue between different artists and their works. The section Back to the Future will look at artists from all around the world, whose own innovation led to the conversations and perspectives that are currently present in the art world. Six art prizes, including the Illy Present Future prize, will be awarded.

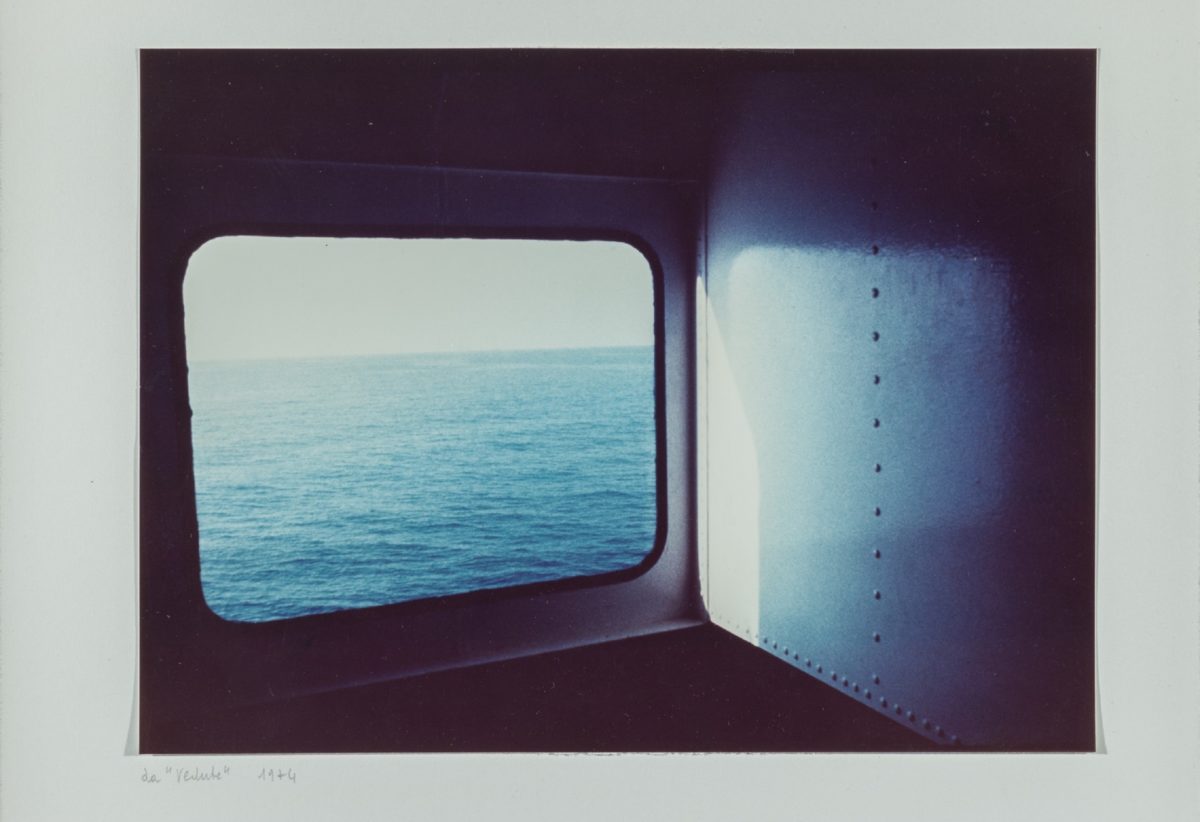

Offsite Projects include Telephone, which looks at the telephone as a means of artistic expression and Abstract Sex, which hones in on the fair’s theme of desire, finding links between bodies, objects and machinery. The central concept is apparent from the very start, as its theme, designed by graphic design company FONDA and appearing on its website and promotional material, taunts the viewer with images apparent but just out of sight through cutout holes. Partly hidden, the images are rendered ever more appealing and desirable through the juxtaposition of their nearness and their inaccessibility.

This desire created through unapproachability is something that director Ilaria Bonacossa wanted to play with in the artworks on show at the fair. “Desire springs from the relationship between the body and society,” she says, “between experienced reality and an imagined, coveted existence.”

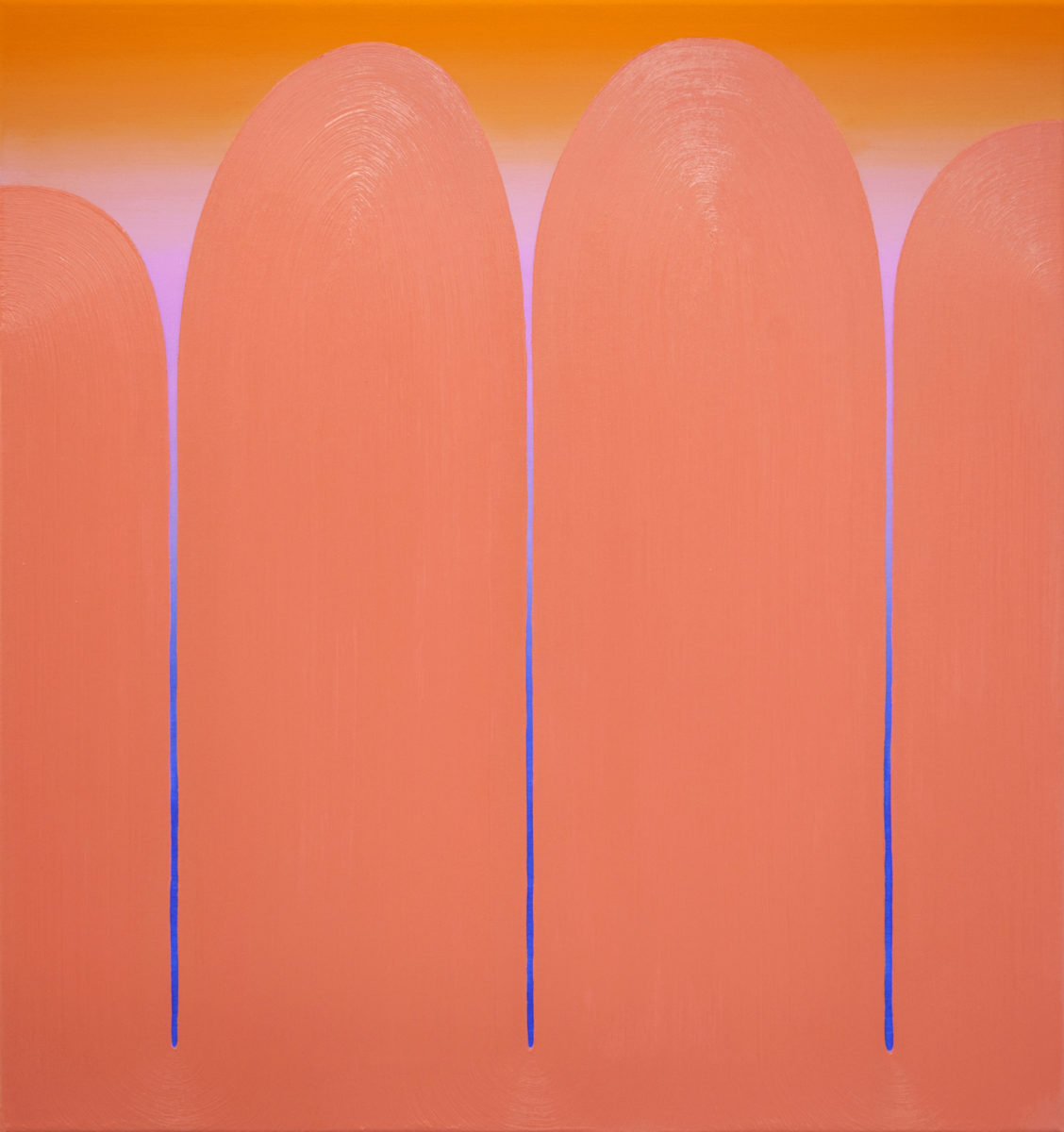

Osamu Kobayashi’s Touch seems to invite us to do just that, and yet our inability to quite pin down what these enticing shapes are obscures our determination—are they dripping breasts? Or fingers held up in a gesture of greeting? Or is this an image of arches, our determination to perceive a human element merely an effect of pareidolia?

“The images are rendered ever more appealing and desirable through the juxtaposition of their nearness and their inaccessibility”

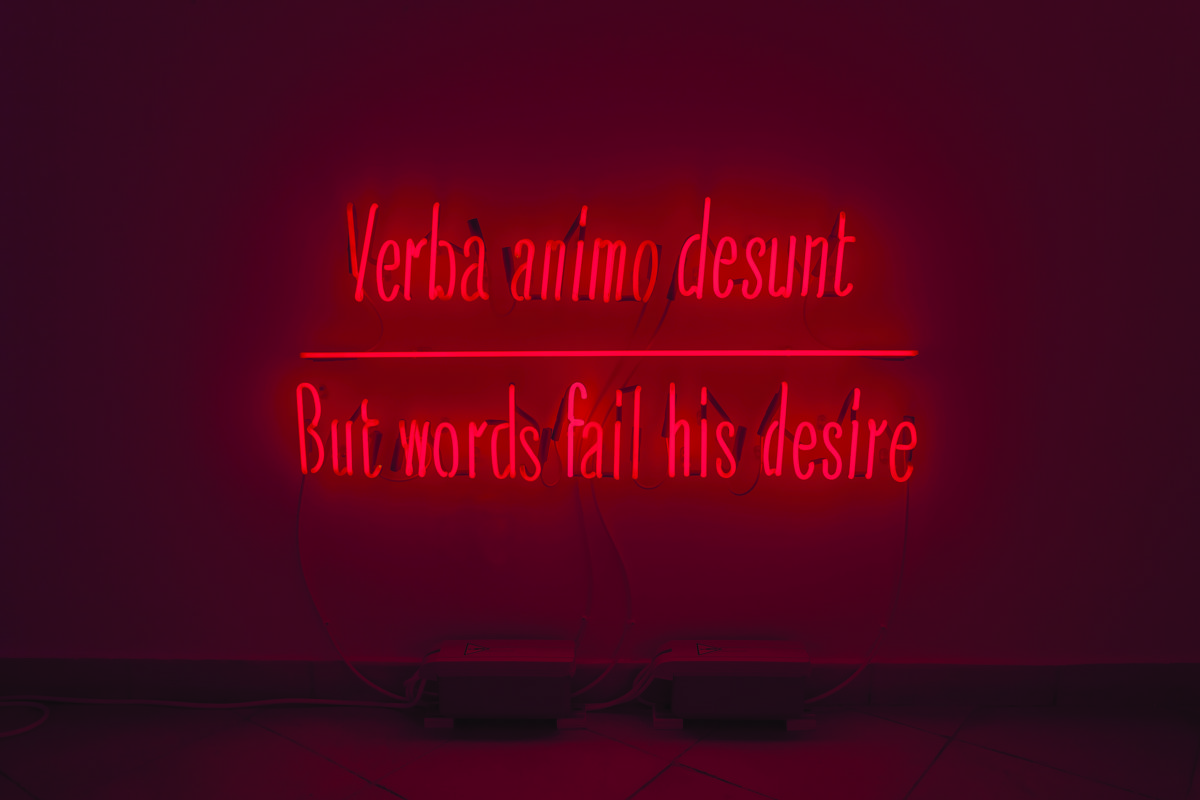

Albrecht Schnider’s Untitled (Portrait) shows what appears to be a woman, hair elaborately coiffed and earrings dangling, as though she has tried hard to maximise her own desirability, and yet her face is blanked out, hidden from view. Joseph Kosuth

’s neon sign shows how the inaccessibility of the desired object is often a result of our own inability to express articulations of longing, its red glowing writing conjuring up the colour of desire and connotations of sleazy neon-lit clubs, where the desired object can be in such proximity and yet be no less unattainable.

Repeated references to refugees, for example in the work of Oliver Ressler

and Badi Badalov, show that desire is not always about the sexual, and that a longing for freedom and security often meets these same criteria of something being just within reach—sometimes just inches away from the border of a safe country—and yet impossible to attain, as faceless bureaucracies deem that you yourself are not sufficiently desirable to be allowed to cross.