In an extended run at The Photographers’ Gallery after a cancelled tour to Frankfurt, the 2020 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize exhibition brings together the nominated works of Mohamed Bourouissa, Anton Kusters, Mark Neville and Clare Strand. The exhibition encourages the viewer to consider the plasticity of photography as a medium, questioning where its formal boundaries lie and the extent of its representative capabilities.

In the case of Mohamed Bourouissa, images are taken from five projects created over a 15 year period, originally presented together in his 2019 exhibition Free Trade at Rencontres d’Arles, France. Bourouissa creates documentary-style work focusing on the communities living in the “banlieue” suburbs of Paris, an area which has over time become a contested byword for economic deprivation and rampant social inequality in the country.

In one image of an arrest, an unclothed man looks up longingly at a second figure, while the head and shoulders of two heavily cloaked police officers who restrain him remain out of shot. It’s a powerful shot, contrasting the knowability of one relationship with the coded nature of another. The officer’s hand signals an immediate and future coercion; the hidden right-hand figure could alternately be a subject of desire and comfort, or malice and betrayal.

“It’s a powerful shot, contrasting the knowability of one relationship with the coded nature of another”

English photographer Mark Neville continues the French theme through a British lens. While Bourouissa attempts to capture the essence of a whole nation through the eyes of a stigmatised group, Neville immerses himself in the iconography of particularity, integrating choreography with Bourouissa’s more journalistic, revelatory style. In Parade (2019), he focuses on a farming community in Guingamp, Brittany over three years from 2016, Neville’s images reveal the relationship between the people and the land, while a discordance emerges between the original agricultural contexts of hunting and horse riding, and their parallel status as class signifiers in the artist’s home country.

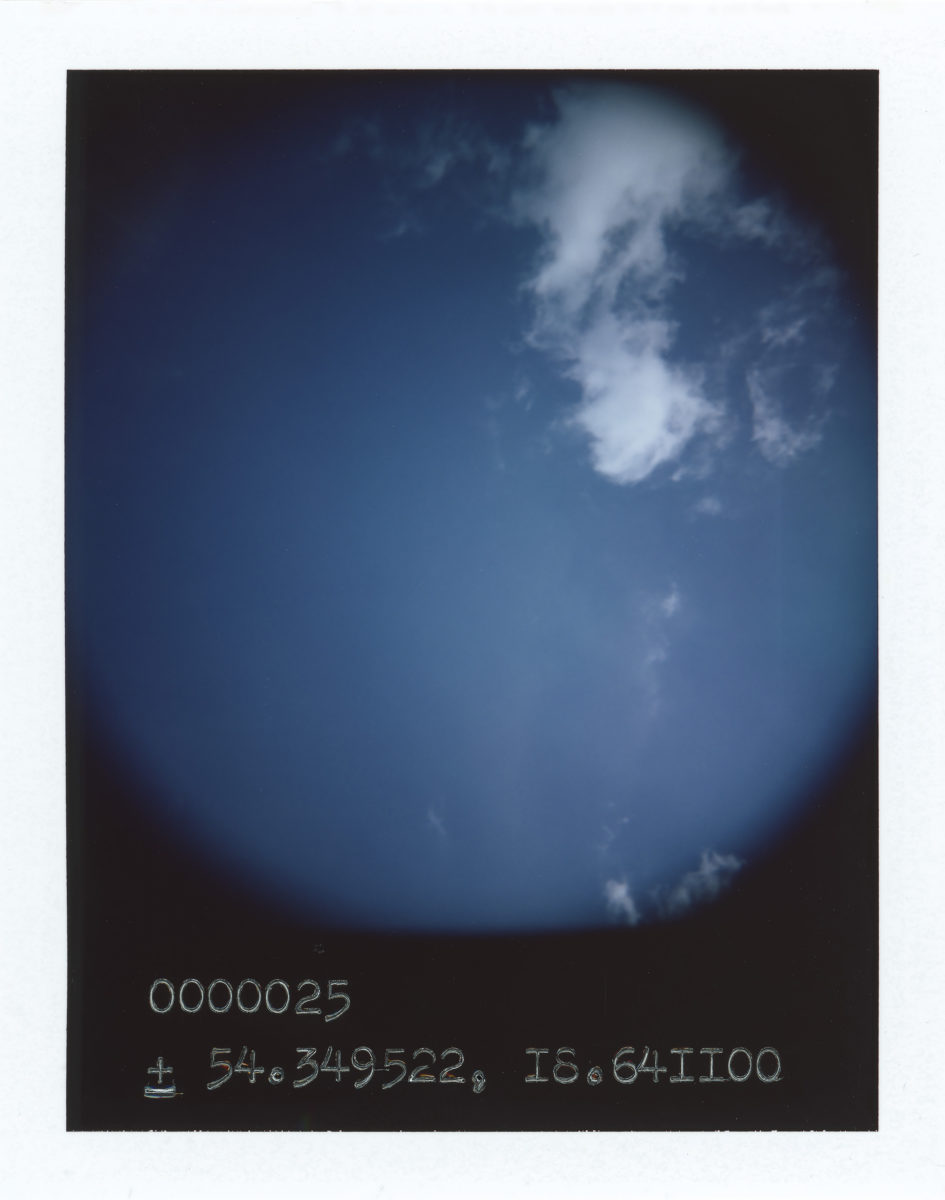

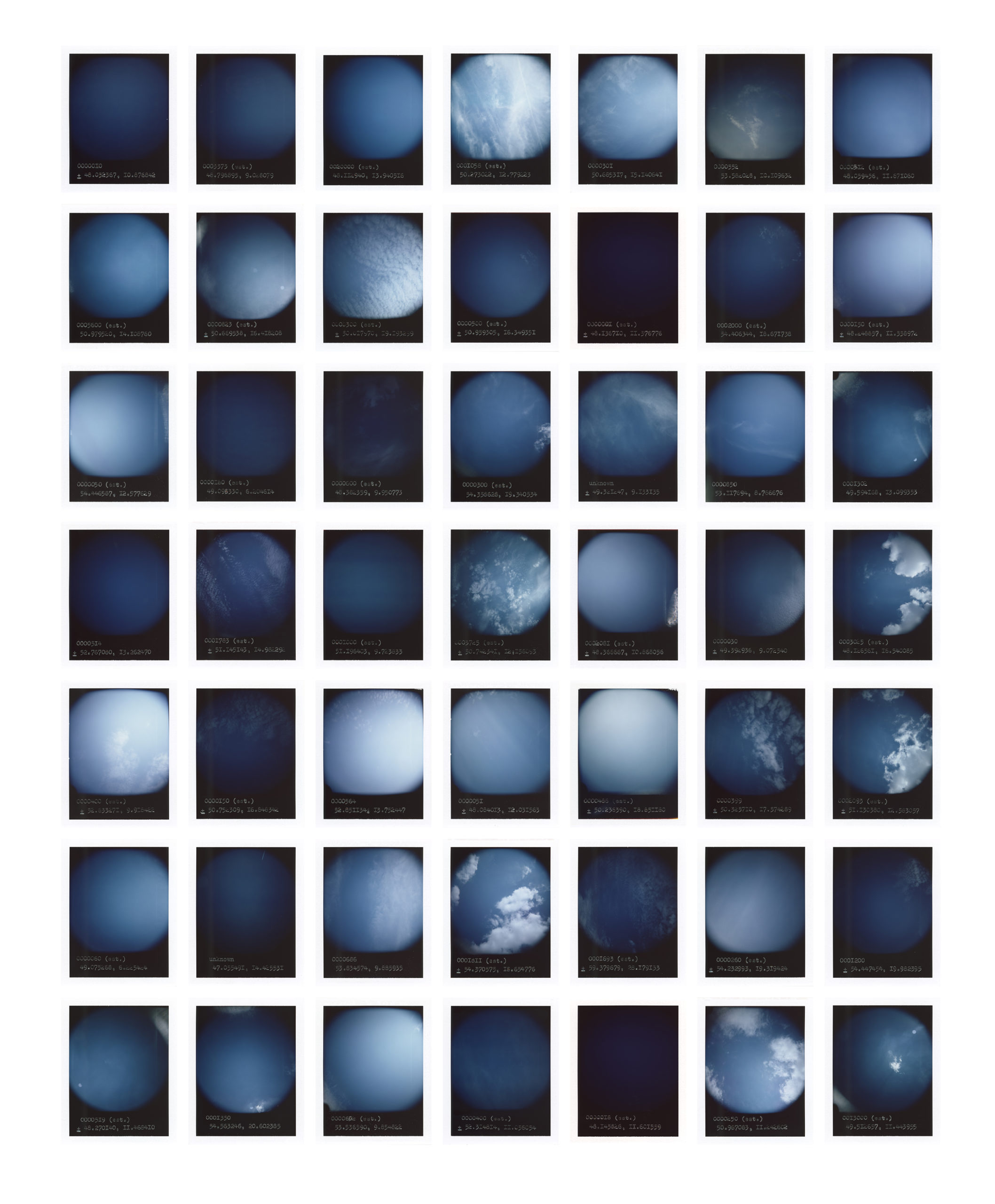

In contrast to this documentary style, Anton Kusters’ entry is a study of ineffability and resolution: the things artists turn to when forced to look away from darker realities. Hoping to trace his grandfather’s fate in an unknown Nazi concentration camp, Kusters’ visited Auschwitz, but found himself unable to synthesise work from the trauma on display. He instead turned his camera upwards, creating 1,078 polaroid images that capture a blue sky at the last known location of every former Nazi run concentration and extermination camp across Europe from 1933 to 1945.

The coaster-sized photographs are arranged in a strict grid, with the estimated number of dead at each location scribbled at the bottom. The sea of blue is dominant from afar, creating a sense of serene unity to counter, but not extinguish, the knowledge of the artist’s original roadmap. A bubbling audio score by Ruben Samama adds to the sensation of self-aware escapism.

Clare Strand, Information Source 3

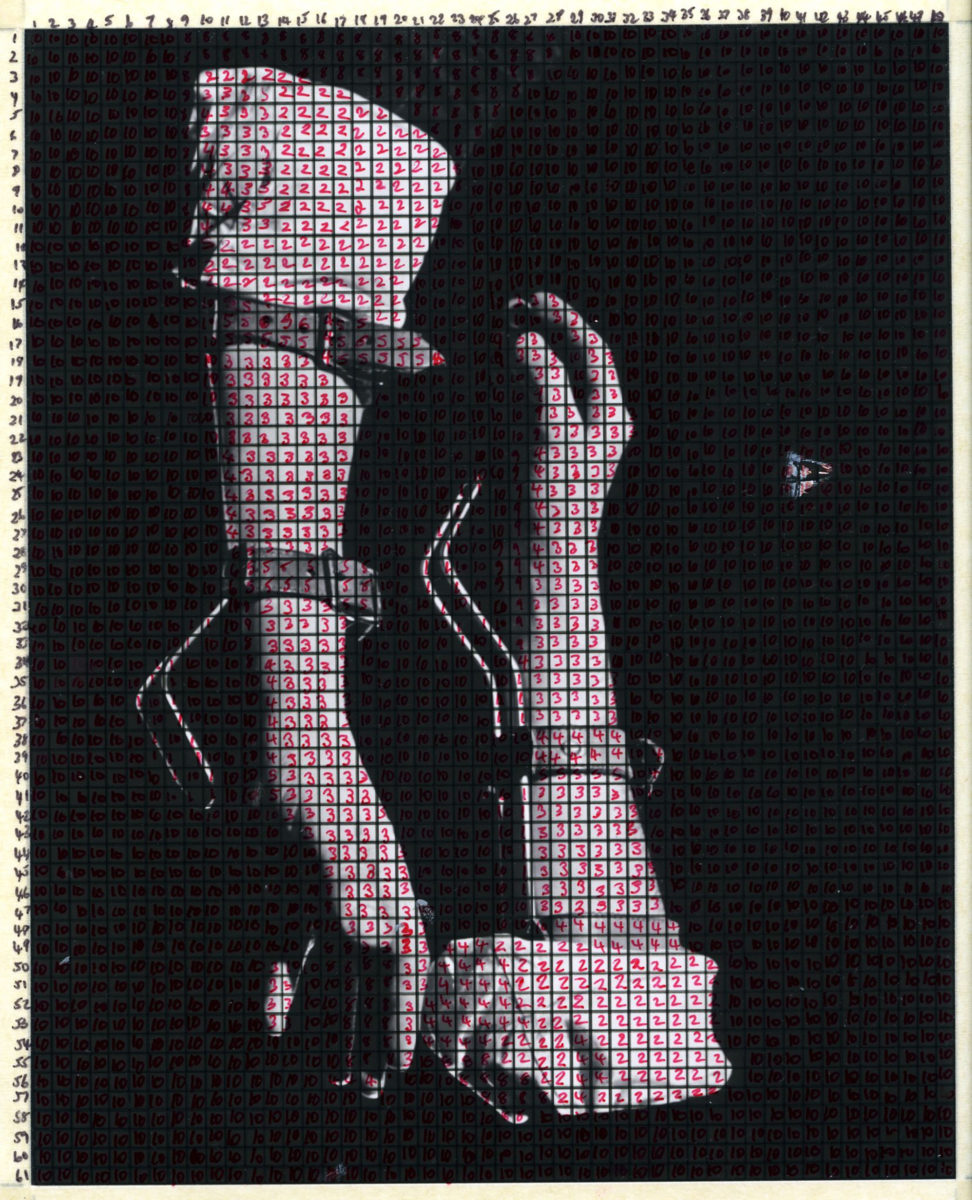

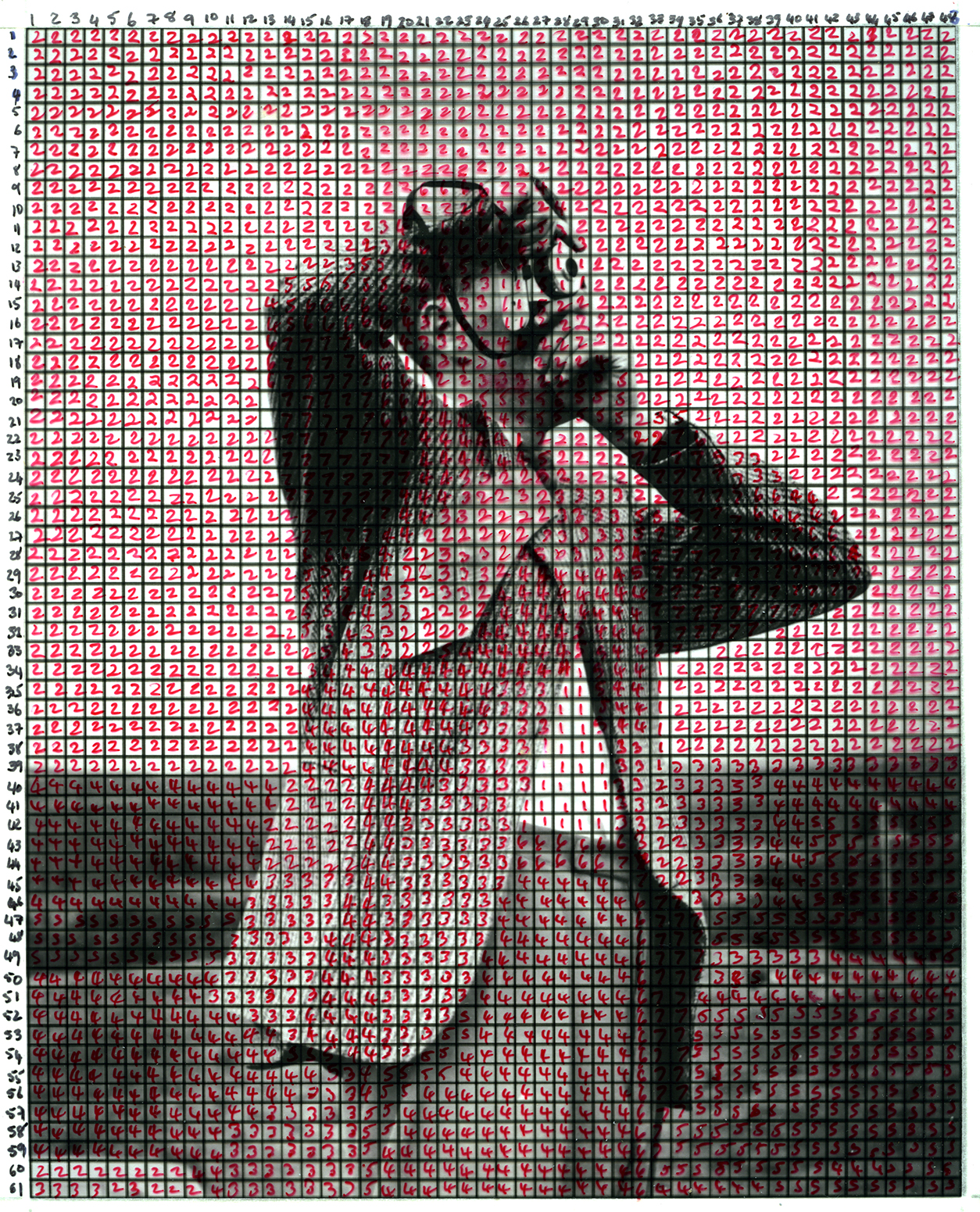

While Kusters work shows photography’s ability to narrate a single event in history, Clare Strand explores ideas of transmission and authenticity within the medium as a whole. Her project, The Discrete Channel with Noise (2019), sees Strand recreate photographs in paint using a numbered grid system. Her husband selected ten photographs and assigned each a series of numbers according to the tone of each segment. He then read the number sequence to Strand down the phone, from which she was able to reimagine the image using ten shades of white, grey and black paint, each corresponding to the tone of the originals.

The result is a comment on transmission and interpretation: how accurately can photographs be recreated in other media? And crucially, what is lost in the process? It’s a fitting, metatheatrical ending to an exhibition which, through its subtle variations, unravels the full range of photographic possibility.