This Artwork Changed My Life is a fortnightly series of personal essays that share the stories of life-changing encounters with art.

When did your relationship with art begin? Did you go to galleries as a kid? And do you remember the first time you were in a gallery? Was it weird or heavy? Did you enjoy yourself? Do you remember the art you actually went to see, or is the vibe of it all the only bit you have left?

My childhood was a warm pocket. I was small and the world felt wide, but I was safe within the limits of a nuclear unit: my mum, my dad, my little sister and me. It was insulated, middle class, the 1990s, London suburbs. I wore dungarees, had wild baby hairs that stuck out in wispy tufts, and my grandparents loved me. I was so shy—I would go red when people spoke to me and I wouldn’t look adults in the eye when I replied to their questions.

On magical weekends, my parents would bundle us onto the tube and take us into Zone 1. Me and my sister had matching silver puffer jackets. I remember how the seats on the Piccadilly line felt as a small child, the way the shape of it covered and held me entirely. Me and my sister would yell out a countdown: “18 more stops until South Kensington!”, pointing at the display when the station names flashed past.

We were off in search of The Spectacular, the quiet dazzle of a blue whale strung up against a golden ceiling, a rock as old as the solar system itself, an animatronic gorilla lit up purple from behind, smoke machines. My favourite was the Natural History Museum, because of the massive diplodocus parked in the entrance hall. I would wave hello to every skeleton we passed. If we were good, we would go to the Rainforest Cafe for dinner, and I loved it, even though I was shit scared of the fake crocodile in the wishing well and the thunder soundtrack that played overhead.

“My dad will tell how I pointed at a Monet and said ‘I can do better than that!’”

I didn’t go to galleries as a kid, I didn’t need or want to. My parents didn’t see the value in taking us along to them I guess, and fair enough. Painting was rare, distant; it wasn’t part of my cultural landscape, and I am not sorry about it. I still had an expansive frame of reference for what I wanted from a weekend.

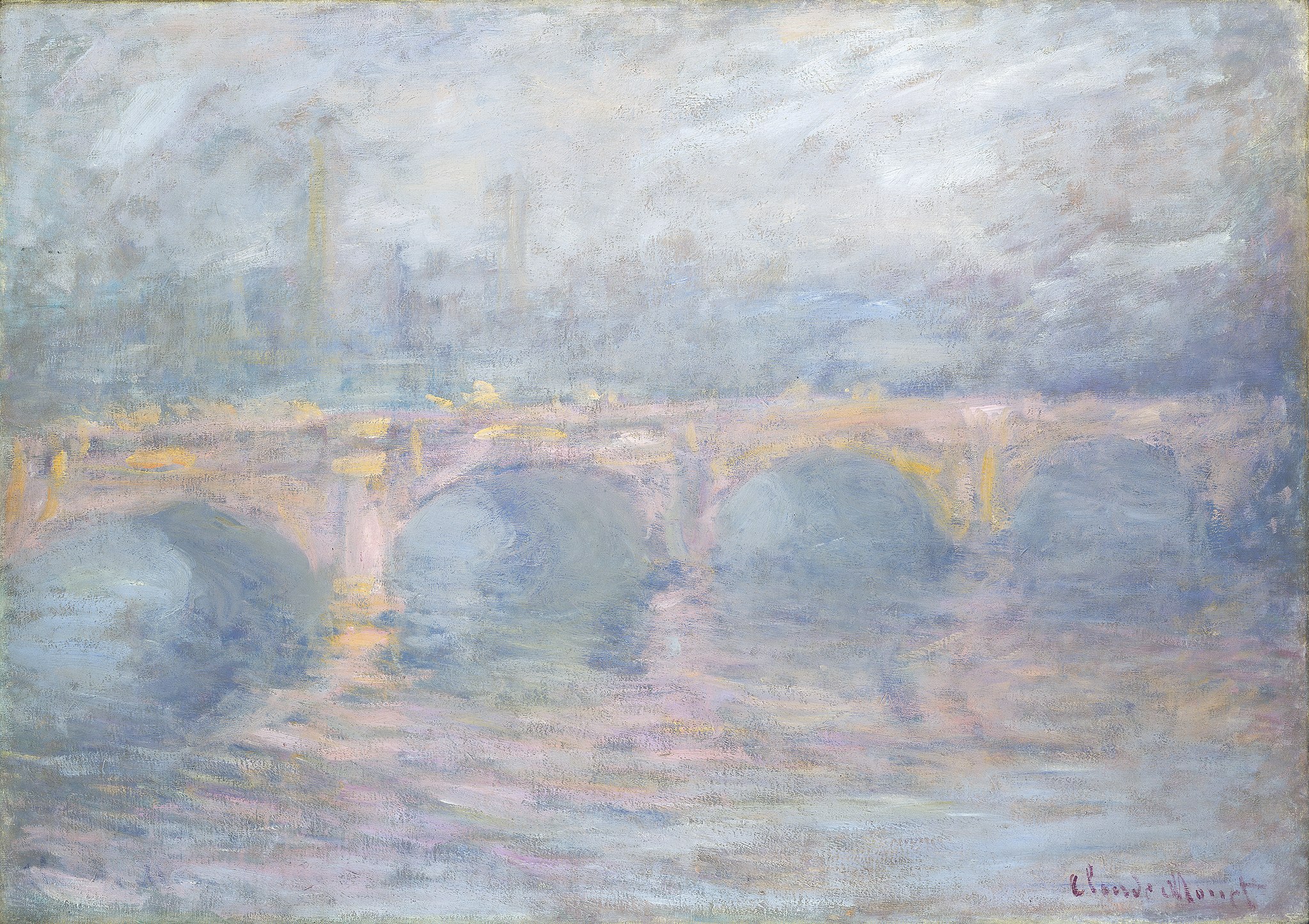

I think I am here in the art world by fluke, pure chance and the seat of my pants, so it always feels like I am writing on borrowed time. But if you ask my dad, he will tell you that I was meant to be a critic. He will tell you a story about how I pointed at a Monet and said “I can do better than that!” Apparently, the story goes, my dad saw the posters on the tube platform on his way back from work one day, some big fuck off Monet retrospective.

My dad grew up in Tottenham, came up under Thatcher and the wild wild West that was London in the 1980s, and now he was this boy-done-good: wife, two kids, a car and a mortgage. His dad was born in a tin hut, on the banks of a river, and here he was standing in the centre of a city, with disposable income. I think, at the time, he must have believed in some kind of bootstraps mythology, some kind of thinking around exceptionality and hard graft. Stood on that tube platform, with that identity behind him, he thought Monet was pretty classy, and the slick images of glassy landscapes rendered through hazy painting just grabbed him.

He took me to the National Gallery to see it, on one of these magic weekends, and as we were traipsing through I stopped in front of a painting. Apparently I tried to touch it, and when my dad explained that it was worth a lot of money, I looked up at him, confused, and said “I can do better than that!”

It made him laugh, but he didn’t think much about it until I found myself doing this mad job, where I chat about art and people actually listen. Now, to him, it feels like fate or destiny, like magical thinking or a warning sign that it was meant to be. He feels this pride that, through pure chance, he played a hand in setting up this silly fluke. If you ask my dad, he will tell you that that Monet probably changed my life.

Memory is unstable, but I remember being in that gallery. I remember wearing black wool tights, I remember holding my Dad’s hand as it hung above me. I don’t remember waterlilies or gestural brushstrokes, but I remember the beigey floorboards lit up warm by spotlights. I remember whispers, I remember the gallery being a bit empty. The idea that I yelled in a hushed gallery is at odds with my memory of a gently embarrassed childhood, but I like the image it paints of me as this furious sitcom character.

“The idea that I yelled in a hushed gallery is at odds with my memory, but I like the image it paints of me as this furious sitcom character”

Isn’t it strange: the things we remember as small children? What we take with us, carry through to our adult bodies. Between experience and feeling, what makes up memory? If you went to galleries as a kid, what do you remember about them? I only ask because I want to compare, I only want to see if I measure up. Recently, I can’t stop thinking about how my suburban middle-class pocket childhood was so, so far from the childhoods my parents had, the way my life and choices are built on their ability to transform aspiration into solid fulfilment.

Immigrant desire is so rarely materialised, so it comes back again and again in all these different shapes, using these satellite shapes as proxy for its own lack of body, to hold itself still. Maybe it is a kind of ghost, returning to haunt or seek retribution, playing the long game. I can’t stop thinking about why I am a critic, and why my cousins aren’t. How did my dad feel when he saw that poster on the tube platform across from him? What part of him did it speak to, what did it conjure and why did he feel a pull to take me?

My mum kept the little gallery leaflet we brought back with us. It is tucked away in the shed somewhere, in a plastic storage bin with wedding photos and 56 years of birthday cards. I don’t believe in flukes, not really-really. I think there is an inevitable distance to collapse, between experience, desire and received wisdom: that a painting, in that moment, became a host for something else.

Even though that was the only time I went to a gallery as a kid, I think my parents still tried to hand me culture like it was a rarified thing. There was spectacle and smoke machines, and then there was culture on a wall, that I had to react to. I have been stitched up, fluked into playing the long game, trying to justify how I could spend a lifetime looking for a painting I can wave hello to as I pass it by.

Zarina Muhammad is a writer, art critic and artist. She is the co-founder of The White Pube, an online criticism platform focused on art, video games and food.