A sequel to the original exhibition which took place at Gagosian’s New York branch, Social Works II presents artists from the African diaspora and “their insights into the relationship between space (personal, public, institutional, and psychic) and social and artistic practice.” What does this all mean? The ubiquitous phrase ‘taking up space’ (encouraging those normally denied room and attention to believe that they deserve it) offers one possible reading given that the artists have been brought together according to their ethnic origin . But the show also has a literal dimension: architectural sculptures occupy space in a way that hung paintings and photographs don’t—sound and video works bring audio to quiet spaces, redefining them in the context of their contents.

There’s urban theory too: artworks that deal with city planning, community-building and their effects on Black communities. Frederick Douglass, the subject of Isaac Julien’s works, occupies a commanding space in the African American cultural consciousness and psyche. How can Black art capture these various nuances and dimensions? These are the types of questions curator Antwaun Sargent hopes to answer in his various projects with Gagosian (he was appointed a curator and director earlier this year). From serene photographic landscapes to social-media prompted oil paintings, Social Works II gives 11 artists a chance to offer their own answers.

Grace Wales Bonner, Darkness and Light, 2021

Wales Bonner’s eponymous fashion label already champions emerging photographers such as Nick Sethi, but Darkness and Light sees the British designer branch into sound-based art. Vintage teak-style bookshelf speakers are arranged like building blocks in the installation, which also features pamphlets, flowers and shells as the artist constructs a shrine to the Black Atlantic by honouring cultural ritual and memory.

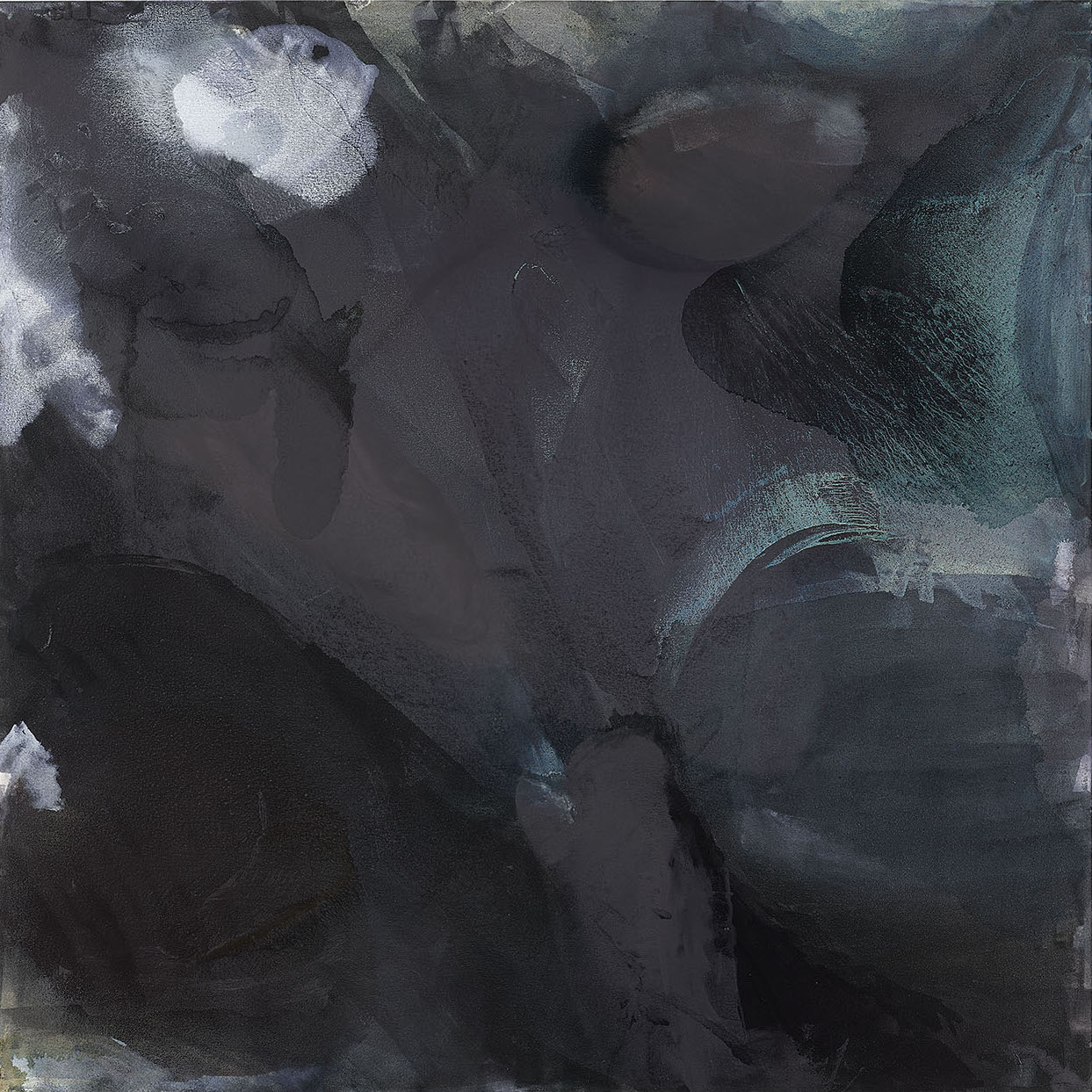

Amanda Williams, What black is this you say?—Although rarely recognized as such, ‘The Candy Lady’ and her ‘Candy Store’ provided one of your earliest examples of black enterprise, cooperative economics, black women CEOs and good customer service”—black (07.24.20), 2021

Responding to the social media ‘blackouts’ that followed the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, Williams interrogates the nature of colour and activist aesthetics in What black is this you say. The artist used her own Instagram page to identify a different shade of Black each day, encouraging links with abstraction and experimental readings of race and colour. The canvases are that digital exercise translated with oil, giving them added depth and impact.

Isaac Julien, To See Ourselves as Others See Us (Lessons of the Hour), 2021

This photograph is a still from Julien’s Lessons of the Hour, his 2019 film dramatising the life and activism of the pioneering American abolitionist Frederick Douglass. The ten-screen installation combines readings of Douglass’s speeches in modern settings with narrative retellings of the former slave’s encounters with family and fellow thinkers, focusing on his travels in Scotland between 1845 and 1847.

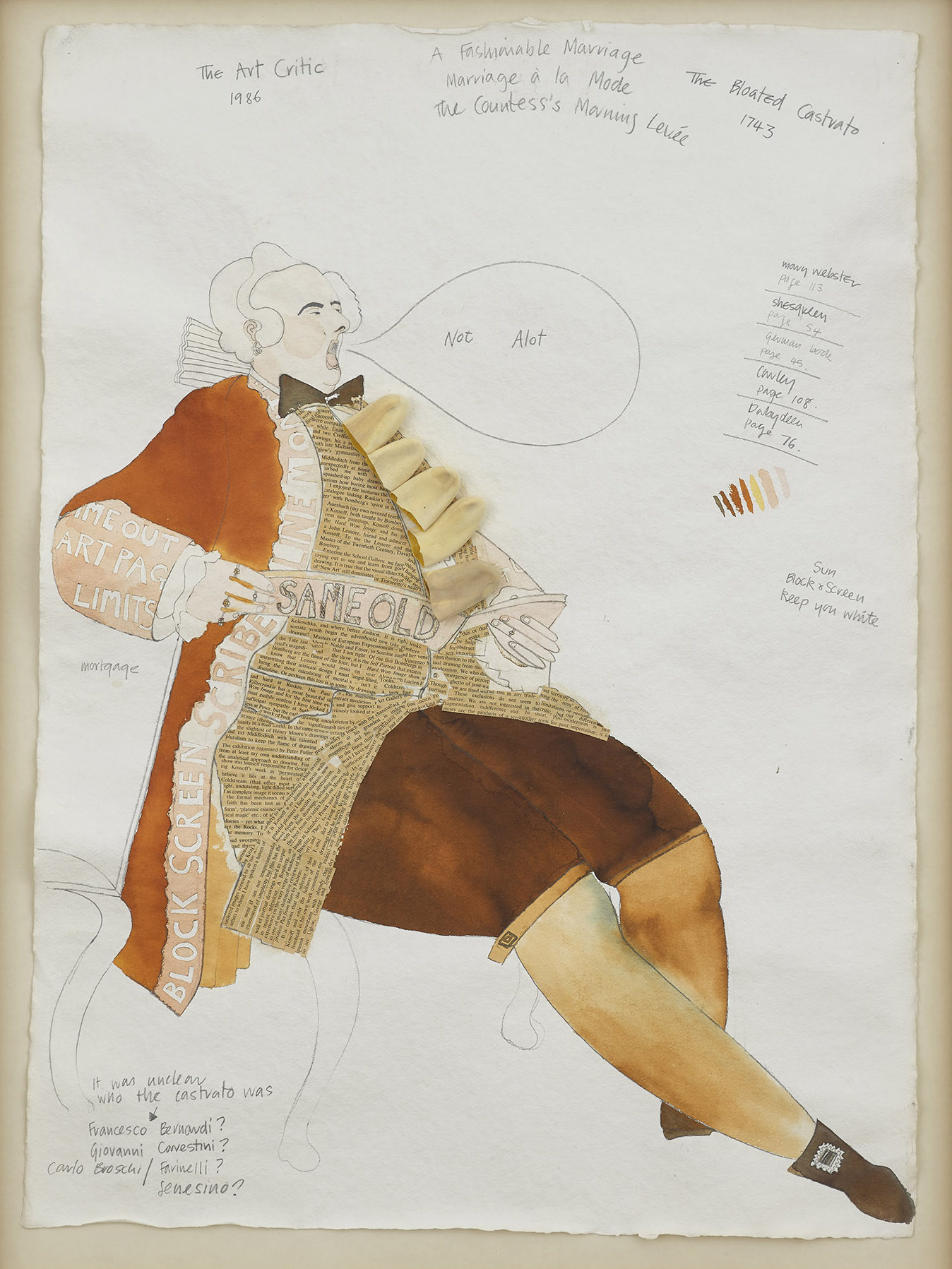

Lubaina Himid, A Fashionable Marriage: The Art Critic, 1986

The 2018 Turner Prize winner responds to William Hogarth’s Marriage A-la Mode, the English painter’s 1743 series of six pictures and accompanying engravings critiquing the exploits of the aristocracy. Hogarth’s origins warned against marriage for wealth rather than love, though Himid widens her scope to target the slave-trading classes in general. The artist’s notes on Hogarth’s originals surround the bloated figure: pondering the identity of a certain Castrato singer, for example.

Tyler Mitchell, Georgia Hillside (Redlining), 2021

Zooming out from his fashion and portrait photography, Mitchell returns to his native Georgia for this new series, exploring the tension between the American pastoral idyll and the racist history of the southern states. The first African American photographer to shoot a Vogue cover when he captured Beyoncé in 2018, Mitchell continues to focus on Black subjects in his work. Here the red lines evoke partitions, maps and boundaries as friends relax on the hill.

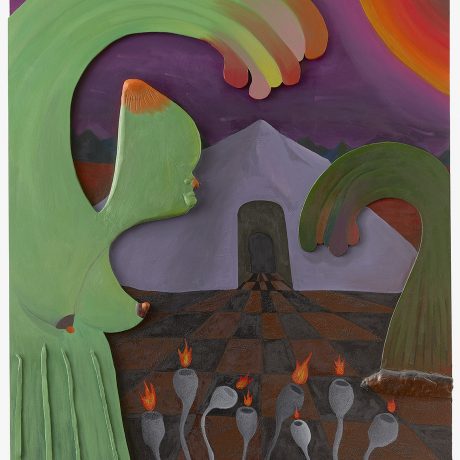

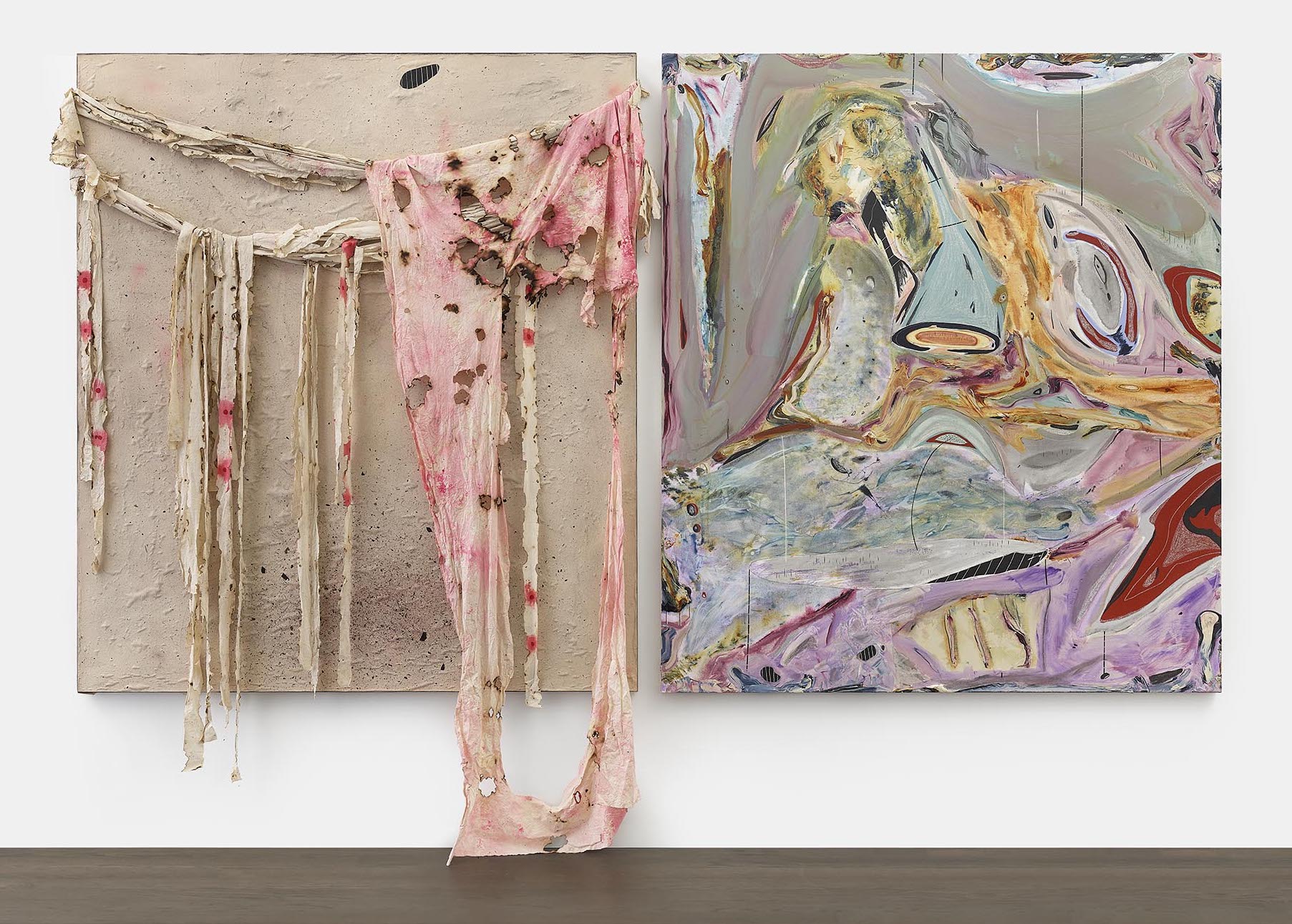

Manuel Mathieu, toofarfromhome, 2021

Abstract forms composed of soil, fabric and tape drape and drip across Mathieu’s works. The artist’s Haitian upbringing informs the diversity of his practice: surreal figurative faces sit alongside ceramics, polaroids, and the messier shapes of toofarfromhome. Mathieu, who has previously responded to Haiti’s dictatorships and politically motivated violence in his practice, burns and knots the fabric here, evoking violence, while the second panel adopts garish and unsettling colour combinations.

Kahlil Robert Irving, Dreams in the line and memories (/whipped) [detail], 2021

Resting on wooden palettes in the centre of the gallery, Irving’s sculptures feature hand-pressed ceramic tiles arranged in neat squares, which are then layered with chalky fragments and sliced-up advertising and newspaper fragments referencing racial segregation (a spliced ‘Whites Only’ sign is visible). “How are our histories packaged?” the artist wonders, “Are they cemented into the layers within us or beneath us? When do we resolve them?”

Rick Lowe, Black Wall Street Journey #17 (Greenwood), 2021

In 1921, mobs of white civilians attacked a prosperous Black neighbourhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma (known as Black Wall Street) without provocation, destroying more than 35 blocks of houses and businesses. Houston-based Lowe continues to respond to the Tulsa Race Massacre, building on the community arts outreach he undertakes with Black Wall Street Journey and Project Row Houses. Inspired by the infinite combinations and social rituals of a domino game, his canvases resemble maps, city households illuminated in the dark of night.

David Adjaye, Asaase II, 2021

The Ghanaian-British architect makes use of a traditional ‘rammed earth’ technique inherited from West Africa for Asaase II. It’s the second iteration of a sculpture series inspired by historic buildings including Tiébélé royal complex in Burkina Faso and the walled city of Agadez in Niger. The material’s horizontal lines resemble growth rings while also pointing to a stringent geometric order, bringing ideas of landscape into conversation with metropolitan London.

Ravi Ghosh is Elephant’s editorial assistant