Guess what we’re talking about. There were some in among Clotilde Jiménez’s colourful collages at Mariane Ibrahim’s Paris gallery. A couple are featured in the Camden Art Centre exhibition of paintings by Canadian artist Allison Katz. And at the Bellevue Arts Museum outside Seattle, 800 cover a huge wall.

“Plates: they’re the unsung part of ceramics,” says London-based Katz, who first began experimenting with the humble dish in 2010. A solo show at Gió Marconi gallery in Milan in 2018 displayed “constellations” of readymade plates that had been painted over with her recurring imagery: from female figures that reference art history, to mouths and noses, eggs and monkeys.

“I wanted to take motifs and ideas that I would have normally painted on canvas and spin them out in the circle,” says Katz of the works that were clustered together on tables and walls. “I was very intrigued by the way that the lack of corners seems to derail the seriousness of painting, and in the inherent domestic familiarity of the plate. I was trying to undo the hierarchy.”

She’s not the first to reappraise the plate’s decorative value. Picasso turned his hand to ceramics in the 1940s, collaborating with the Madoura pottery in the French Riviera town of Vallauris to create editions as well as unique pieces. Then there’s Grayson Perry, whose name is often associated with the contemporary elevation of ceramics. For Katz, “the gamut of plates in contemporary art runs from Judy Chicago to Julian Schnabel. I love those Schnabel paintings with the plates,” she says of the series that the American painter began in the late 1970s, adding broken ceramic pieces to the canvas. “They really speak to that desire to smash the decorative.”

“I was very taken with the obsession in 16th-century Italy to make holes in everything, in ceramics, but also in leather and metal”

Chicago’s iconic The Dinner Party (its 39 place settings each centred on a unique hand-painted plate) was a key inspiration for Jiménez’s installation of 21 plates. “My original idea was to create my own dinner table, and invite people closest to me to partake in a celebratory meal,” says the Hawaii-born, Mexico City-based artist. “Growing up in a black Baptist church in Philadelphia, usually after the long three-hour services, we would have a communal lunch at the church or at home where we came together and fellowshipped. It was a special moment. The dinner is a communion that reminds us of where we’ve come from and where we are going.”

- Two of Allison Katz's Traforati editions: Signature, Blazing Yellow and To be Continued Unnoticed. Photography © Filippo Armellin

Titled Deux Ancêtres (Two Ancestors), the piece depicts two black female figures surrounded by floral motifs. “I describe the figures as my two ancestors who I have not forgotten. We eat food from their bodies because they are the source,” says Jiménez, adding that his aesthetic influences for the piece range from Picasso (“I learned a lot from studying his plates”) to Japanese ceramics and Mexican Talavera pottery. The ceramic know-how, meanwhile, came from Cerámica Suro

, a family-owned ceramics studio in Guadalajara, Mexico, which has collaborated with the likes of the Haas Brothers and David Adjaye, and where Jiménez was invited to do a residency.

Katz’s most recent plate pieces also came about via a residency, in her case with the Mahler & LeWitt Studios in Spoleto, Italy, where she collaborated with La Gioconda, a longstanding ceramics studio in nearby Deruta. The two plates at Camden Art Centre are part of an edition called Traforati, with each centred on a different image, hand-painted by Katz, and encased in a decorative (perforated and glossily glazed) border design.

“I was very taken with the obsession in 16th-century Italy to make holes in everything, in ceramics, but also in leather and metal,” says Katz, whose punctured plates were hand-thrown and hand-cut. “The pattern lets in all this space. It’s almost not about decoration at all, but metaphysics. I see it very much in line with Fontana. It’s the idea of breaking the surface and destroying the illusion of whatever you are working on.”

“I was very taken with the obsession in 16th-century Italy to make holes in everything, in ceramics, but also in leather and metal”

The act of painting with glazes (“which have lots of tiny explosions in them”) also appealed. “It’s like painting with chance; you never know how something is going to turn out because of the firing,” Katz says, adding that the shiny finish brings another layer to the work. “The surface itself is really part of the content.”

One particularly ambitious and poignant plate project is The Last Supper by Julie Green, an artist and professor at Oregon State University, who died in 2021, not long after she painted the 1,000th plate in the series she started more than 20 years earlier. Painting on second-hand plates in blue paint, Green documented the last-meal requests of Death Row prisoners in the US.

The first 800 plates are currently installed in the atrium at Bellevue Arts Museum. At first glance they resemble traditional blue-and-white pottery. “You think you’re looking at something that’s very familiar and comforting and then it’s something that really jolts you once you actually understand what you’re looking at,” Lane Eagles, associate curator at the museum, told The Seattle Times.

Massachusetts-based artist Molly Hatch also uses plates en masse, but her aim is to make decorative themes monumental. In 2014, for instance, she created a site-specific 456-plate installation at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. Titled Physic Garden, it magnifies floral motifs from two 18th-century Chelsea Porcelain Factory plates in the museum’s collection across the 6m-high fragmented “canvas”.

“I wanted to take motifs and ideas that I would have normally painted on canvas and spin them out in the circle”

“I am asking the viewer to view plates as one would a painting, elevating the material,” says Hatch, who trained initially as a studio potter and is represented by New York design gallery Todd Merrill Studio. “I work to create a visual gateway for the viewer to rethink preconceptions around hierarchies of art, abstraction, formality, history, and class.” Five of her “plate-scapes” will be included in the Making Place Matter exhibition at Philadelphia’s The Clay Studio, opening in April 2022.

Molly Hatch, Memorandum, 2018. Photography © John Polak

“I am asking the viewer to view plates as one would a painting, elevating the material”

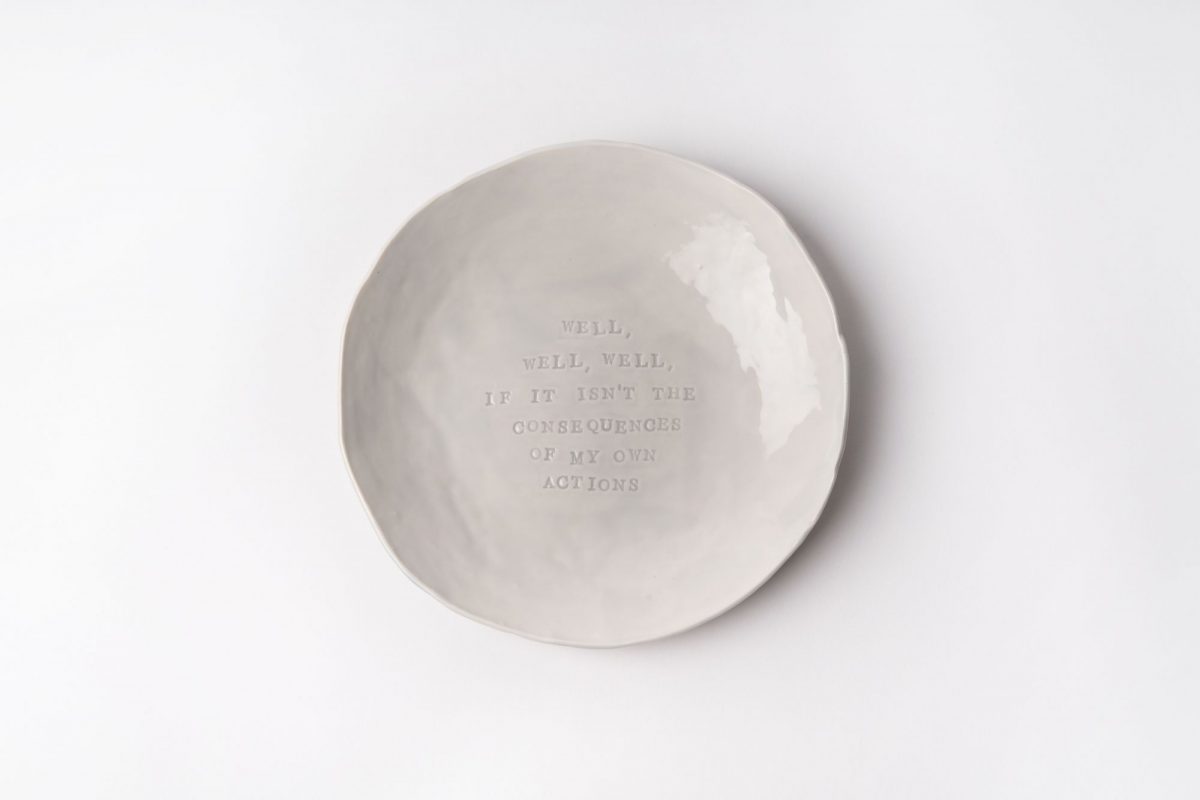

In London, meanwhile, ceramic artist Martha Freud brings a more playful take on the plate to the table. “I started writing on plates about 12 years ago when I needed some plates for my home,” she says. “The first thing I wrote was the quote: ‘I thought I had an appetite for destruction, but all I wanted was a club sandwich’, one of my favourite lines by Homer. Homer Simpson, that is.”

Freud’s new body of unique pieces was recently shown at London’s Nonemore Gallery, her first solo show in nearly a decade. It included a collection of handmade plates, all painted in one single-colour glaze and stamped with phrases such as “I Can Dish It Out But I Can’t Take It” or “I’m Sorry I Acted Crazy. It Will Happen Again”. In April, she will also release ten limited-edition plates with Stoke-on-Trent manufacturer 1882 Ltd.

“They’re my version of an artist’s print,” says Freud. “I make these plates as an expression of my creativity rather than a functional product. But they are really fun to eat off, especially at a dinner party. My favourite plate to serve food on says ‘Do Not Eat Off The Art’.”

Humorous, moving, practical and seemingly here to stay, art on plates serves something up for everyone. Next course please…

Victoria Woodcock is a freelance journalist and former editor at How To Spend It