“There are many hidden spaces in this building,” explains the artist Peju Alatise as we climb up a narrow spiral staircase. We cross the upper floor, past her surreal sculptures, and approach what appears to be an ordinary white-washed wall. Alatise gives it a slight push, and magically, the wall turns into a door. We stand and stare into a dimly lit passage, the threshold to another universe – or simply a back room – in the new premises of the Rele Gallery. “I have the distinct feeling we’re entering one of your artworks,” I jest. “Is this part of the exhibition?” Alatise turns, never missing a conversational beat, and gives me a mischievous grin.

Doors leading onto alternate worlds and worlds compacted into the narrow rectangle of a door are exactly the kind of enchantments in which Alatise specialises. Though her new exhibition, We Came with the Last Rain, swaps doors for windows, the concept of the portal is never far behind. Despite the dimly lit passage of the gallery taking us to none other than a small conference room, Alatise’s magic has already worked; the teleportation from one place to another is complete. London life, with all its stresses and strains, has been left behind in order to go, head first, down the rabbit hole – or, more aptly, considering the specular surfaces found in her art, through the looking glass. Either way, when setting up my recording equipment and listening to Alatise’s opening words, I know I’m about to be transported to the terrific and occasionally terrifying realms of her imagination.

And what an imagination it is! We Came with the Last Rain unsettles our sense of reality and unreality, inner and outer, time and place, in equal measure. Continuing with characters from her own novel and her acclaimed works Flying Girls (2016) and Sim and the Glass Birds (which were shown at the 57th Venice Biennale, 2017, and Frieze Sculpture, London, 2022, respectively), We Came with the Last Rain positions us in a fantastical space where clouds are actually the wings of babies and ‘every droplet’ of rain ‘carries a child.’ Introducing Emiogo, a young girl who meets Alatise’s main protagonist, Sim, in this alternate universe, the exhibition becomes an area of childlike play and escape, psychic relations and cosmic revelations. Stepping into this wondrous domain, we encounter immersive installations consisting of diminutive bodies acrobatically dancing, spinning and flying amongst large transparent drops of rain, and the smiling faces of the young reflected back to us in pools of condensation on mirrored panels. We meet gloriously polychromatic paintings and carnivalesque tableaus of beaming children. And we espy life-size sculptures of small girls and boys peering through beautifully embellished and butterfly-adorned casements or balancing in hoops of red, vine-like structures. Confounding fact with fiction, sublunary bodies with celestial ones, the material with the imagined, Alatise brings us into a space as spiritual as it is concrete, a site teeming with the vibrance of the artist’s own mind, as well as that of the child’s.

A consummate griot – “I am a storyteller first and foremost,” Alatise emphasises to me later in our conversation – the artist weaves together Yoruba mythology with her own kind of magical realism. Like much of her former work, her recent art springs from her own writing, which she initially wrote for children – and still does – but now uses as inspiration for scenes adapted and enlarged in sculptures like Sim and the Glass Birds and The Other Side I-V (2022), the latter of which are central to We Came with the Last Rain. Underpinned by an evocative and poetic epistle that Emiogo writes to Sim about the aforementioned children of the clouds and babies falling in fertile raindrops on the land, We Came with the Last Rain is also a window onto Alatise’s own childhood experiences of myth, cultural customs and artistic inspirations. “The show is dedicated to my father’s mother, who created a special oríkì for me – oríkì literally translates into ‘greeting of the head’, but it is a poem or song which blesses the child and expresses hope for their future. So your orí is part of your destiny. It’s your soul, your spirit, your connection to or contract with the other side. Yoruba’s philosophy is that you should send yourself down here in order to fulfill this contract. My grandmother’s oríkì stated that as the daughter of a king, I was too precious to get myself dirty. It said don’t go playing on the farm when it’s raining; don’t get yourself dirty. So rain is part of my oríkì.” Unlike in Alatise’s grandmother’s song, rain in the show is expressed as a blessing, a transitional and transformational element that commingles heaven and earth, bringing with it healing, growth and the gift of future offspring. Depicted in blown glass droplets bigger than one’s head and in smaller reflective glass domes containing a rainbow of children’s faces, rain transmogrifies the viewer as much as it is transmogrified by Alatise’s own hand. In fact, the presence of rain – or its revitalising and replenishing effects – can be espied outside of these harder though no less translucent manifestations in the proliferating colour and flourishing patterns that decorate the window frames, which are part of the sculptures in The Other Side I-V. In this respect, Alatise’s representation of rain plays to Yoruba mythology and looks to the goddess of rain and fertility, Oya, whose power is cited by Emiogo in her letter to Sim. As Alatise confirms, “rain in this show is both mythological and cosmological. There is a special type of rain, and if a woman wants a child, Oya will bless her with it, and she will become pregnant. Followers of Oya know that she sends different types of rain: there’s the rain where everything grows, and there’s the rain – which is like a storm or tsunami – where the goddess is angry. When this rain fell, my grandmother would tell us all to get inside the house, and we would watch the rain from the window.”

It is this memory of standing by the window as a child and watching the rain that Alatise commemorates in the exhibition. Five sculptures of young children standing on their tiptoes or on stools and gazing through open casements are placed in a row in the main gallery. With life-like features and animated facial expressions, the children stand entranced by what occurs beyond the window ledge. But what exactly is occurring beyond the casement in The Other Side I-V cannot be determined since the windows do not open onto a new vista but a mirrored outlook, one which reflects back to us the inquisitive face of the child as well as our own. True to the ludic spirit and childlike curiosity of the show, Alatise here complicates a clear sense of inside and outside, as well as any neat reading of her work generally. Is the world that the child imaginatively revels in cut off from adult perceptions and rationalisations, appearing simply as the hard reflexive interpretation of our own material reality and relationality? Or, by implicating the viewer – literally, placing us inside the window frame – and therefore pulling us into the ‘other side’ where Emiogo and Sim commune, is Alatise highlighting that reality is what we make it, and that where the imagination begins and the ‘actual’ world ends is impossible to determine? Looking through the window and positioning us on the same level as her young figures, we come face to face not just with ourselves but with our own inner child. An opening to a new way of seeing and being, a liminal space ripe with possibility, the window becomes a doorway to our own redevelopment and renewed sense of vision, too.

In the form of the contemplative child we not only espy our own and Alatise’s younger selves, but actual children today. “My own son can stand and watch the rain. We have bay windows and radiators underneath them, and when it’s raining in Glasgow, he’ll just sit there and watch for hours. I sometimes wonder if he’s looking out for the same thing that I used to watch out for as a child,” Alatise observes. Characters like Sim and Emiogo capture then the innocent imaginings and reveries of children the world over. Yet these fictional figures, who speak and dream in the language, cosmology and mythology of the Yoruba people, also parallel the lives and experiences of the most marginalised and underprivileged children in Nigeria. Alatise’s renowned girl-child protagonist, Sim, was partly inspired by an actual nine-year-old who became a house servant in the home of an acquaintance. Encountering this young girl was an education for Alatise in more ways than one: “Initially, I was shocked. I didn’t expect my friend to do this. I reminded her of the conversations we had at school opposing such practices. I asked her where the child’s mother was. What’s her background? She told me the child had come from an extremely poor family and that she was better off with her. She assured me that she was properly fed, clothed and sent to school for her education – an education she would not have had without living with my friend. But I remember going into the kitchen, and this girl was so small that she had to stand on a stall to get to the sink and wash the dishes.” Already an activist who employed her art to explore and speak up for the rights of women and children in Nigeria, Alatise felt conflicted about this encounter with her acquaintance. Far from endorsing this cultural custom, Alatise still recognised that the child was in a far better position than if she had remained with her family, where chances of survival were slim. Reflecting on the position of this girl alongside the fates of many other children in Nigeria (forced servitude, trafficking, homelessness and begging on the street), Alatise started to write about a fictional ‘house girl’ named Sim, who lives and works in the home of a benevolent woman and travels to an imaginary land, unbeknownst to her employer. This humanising characterisation of a figure who could, in effect, be pitied, ignored or derided by society not only demonstrates Alatise’s privileging and empowering of the girl-child in her work but also celebrates the potentiality and beauty she espies in all children irrespective of the circumstances into which they are born. In Sim and the Glass Birds, her titular figure sits and communes with other winged children whilst bright yellow birds nest and flit over their heads. It is a harmonious sight, one where the freedom Sim experiences internally is externalised and extended to those around her. Simultaneously creating and inhabiting this joyous domain, Sim is divested of the reality and responsibility of being a house girl and the adultification this entails. Here and in the works that make up We Came with the Last Rain, Alatise returns Sim to the sheer pleasure and enchantment of being a child; she delivers her to a space of light and levity, flight and fearlessness, to a land that knows no dark. Like with the rain, the life and vision of the house girl does not have to be about dirt, drudgery and deprivation, but hope for what could be – and what is – in the advent of her dreams.

In this light, the sculptures of girls and boys rapt with attention at what exists beyond the ledge of a window symbolises the brighter future so many children look and long for at this time. “I was talking to a man in Glasgow who supplies the paint I use for my sculptures. He asked me what it was for, and I showed him a photograph of Sim and the Glass Birds and told him the story of Sim. It immediately resonated with him regarding his mum. She had a terrible upbringing in an Irish convent after being taken from her mother, and she never got over the childhood trauma. So she tried to escape through alcoholism and drugs, which gave her some relief but eventually resulted in her death. Sim also tries to self-preserve and escape, to shut off from the world through flights of fantasy. Of course, there’s a little bit of a nightmare in every fantasy. Who’s to say which is which? Think of Alice in Wonderland.” We smile together at this reference but also in quiet awareness of how important the imagination is at this time for children who are, quite frankly, enduring the unimaginable, as seen in the Middle East, Ukraine, the Congo and Sudan. But also here, too, as captured in the story of the Glaswegian man’s mother or frequently reiterated in current news reports concerning the rising levels of poverty hitting the most vulnerable in society: children.

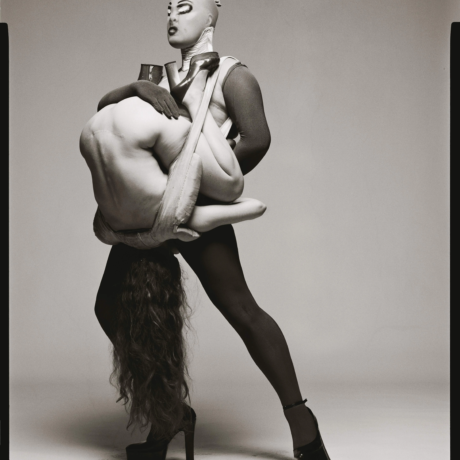

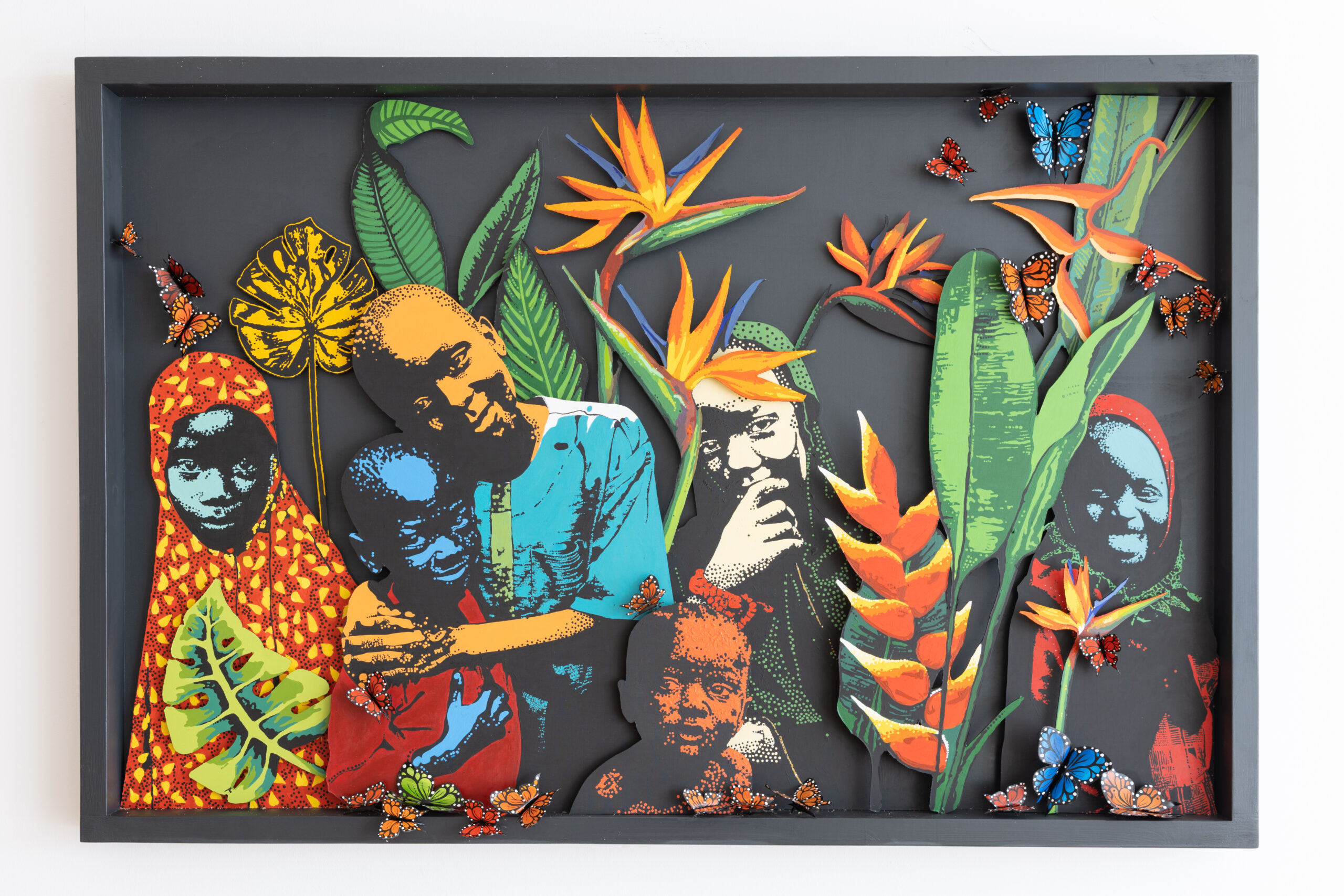

Considering the universal suffering inflicted on children, Alatise’s work could be a lot darker – and it used to be, as is evident by her Venice Biennale work, Flying Girls (2016). Featuring a monochromatically shaded cluster of girls swarmed by birds – and almost becoming winged creatures themselves like the Greek myth of the Pierides – Flying Girls captures something of the trauma endured, as well as the resilience maintained, by the girls abducted by Boko Haram. Despite the dramatic rapture of beastly bodies coating and coaxing young female ones to fly, Flying Girls looks, like We Came with the Last Rain and Sim and the Glass Birds, towards futurity – however dismal or dangerous it might be. Works like Nation Interrupted (2016), on the other hand, allow no such reprieve. Trauma here is forcefully enacted on and incisively expressed through the body of the figures. Greying terracotta limbs lie strewn and smashed underfoot, heads are caved in and ochre clay innards collect disconsolately on the hard, indifferent floor. Bodies are hemmed in by other forlorn figures or rusted door frames which lead to nowhere. Collective historical trauma is displayed in all its cracked glory, the corporal assemblage too broken to undergo any form of retribution, restitution or reparation. In its amnesiac grey, Nation Interrupted is trapped in the hardening hurts of the past; the future forever eludes its stuck and shattered victims. But for Alatise’s child-protagonists, imagining a future with them, through them, for them, is imperative. These works issue colour – like the “sexy yellow” Alatise had made especially for Sim and the Glass Birds, a vivid yellow she hoped would make the audience want to “lick it” – and pattern in abundance; in doing so, they invite hope where it might be lacking, strength where weakness is expected. Tailored to the dimensions, perspective and proportions of actual street children of whom Alatise and her photographer Adeyinka Akingbade make portraits, We Came with the Last Rain looks not only to the future babies longed for by its narrator Emiogo, but also the new worlds these children could create, new worlds they already embody and the new worlds they deserve to inherit despite the current state of our actual world.

For Alatise’s addition to the Venice Biennale for Architecture 2021, doors revealed or concealed mysterious beings, mythical personas and marvellous embodied moments between the imagined and the ‘real’. Alasiri: Doors for Concealment or Revelation literalises a Yoruba belief that “’a person is like a door: to open it is to become part of its secret.” Peering around open doors, a whole troop of fantastic divergent bodies emerge, challenging our preconceptions and courting our desire to know more. It is this desire to know and encounter more that Alatise plants in her heroines in We Came with the Last Rain; it is this quest for future knowledge and experience that we, together with her children, look for beyond the frame of the window. Opening doors onto the past, creating windows that look to the future, Peju Alatise’s We Came with the Last Rain is a wonderland of wisdom as well as fantasy, a future foray promised not just to the children of yesterday or today but those of tomorrow.

Written by Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou