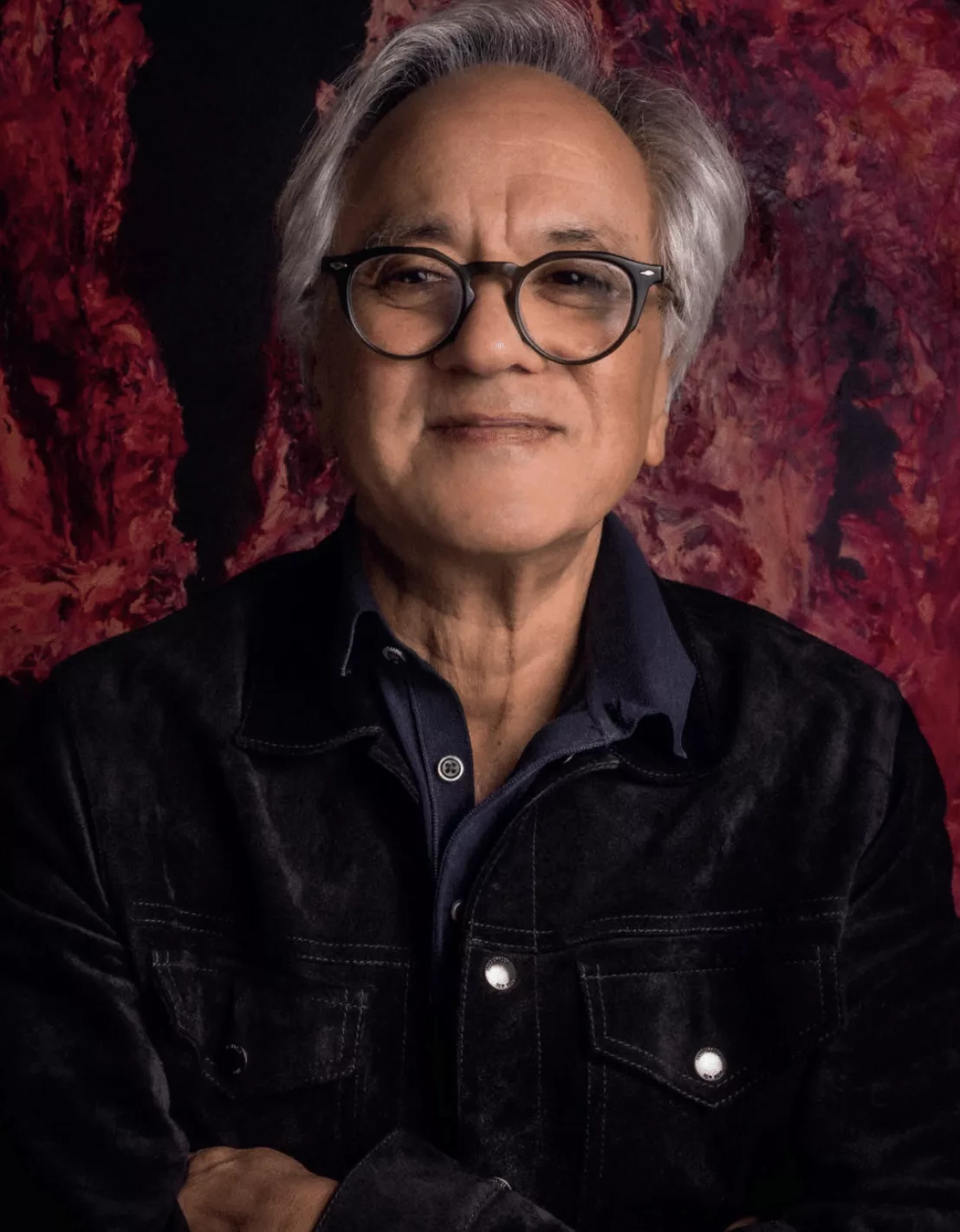

Renowned sculptor Anish Kapoor and Elephant editor-in-chief, Tschabalala Self share words on public space, mythology, the capitalist agenda and the blackest material in the universe in anticipation.

Anish Kapoor is one of the most influential sculptors of his generation. Perhaps best known for public sculptures that are both adventures in form and feats of engineering, Kapoor manoeuvres between vastly different scales, across numerous series of work.

Immense PVC skins, stretched or deflated; concave or convex mirrors whose reflections attract and swallow the viewer; recesses carved in stone and pigmented so as to disappear: these voids and protrusions summon up deep-felt metaphysical polarities of presence and absence, concealment and revelation. Womb-like, forms turn themselves inside out, and materials are not painted but impregnated with colour, as if to negate the idea of an outer surface, inviting the viewer into the inner reaches of the imagination.

Tschabalala Self: Where are you today?

Anish Kapoor: I’m at a hotel in New York.

TS: What brings you to New York?

AK: The installation and opening of my new show at Lisson Gallery, which opens tonight.

TS: Where did you come from most recently? Where did you fly in from?

AK: Oh God, where did I fly in from? Venice, London and then New York.

TS: Is it correct that you’re based in London and Venice?

AK: I’m sort of in a race between the two.

TS: You’ve been deemed one of the most influential sculptures of our time, creating works that have captivated viewers around the globe. Most impressively, your practice has escaped the confines of the white cube: many of your most iconic pieces are public works. Why do you believe your work has been so successful within the public realm?

AK: How on earth can I answer that? I guess, historically we—and I use “we” very broadly, across the globe—have understood that public space in various ways, whether it’s the village, the town square, the inner-city or wherever—the public space has deep symbolic realities. But, strangely, we’ve lost much of that. We’ve lost much of the symbolic power of shared space. It’s as if the capitalist agenda for the maximizing of square footage across most of the Western world has higher value than any shared public agenda. What a crying shame, and how pathetic of us on many levels! So it comes to be the role of public art to re-engage public space, so that when you look at something, you’re sharing that look with your compatriots, your neighbours, whether you know them or not. And that’s an act of a strange, unspoken, but real solidarity and it has to do with this mysterious thing called “scale”. Scale isn’t about the size of the thing. Scale is about meaning. Scale is about the relationship between the work and the body. It’s curious, really, and it seems as if we’ve forgotten that. The public space is full of monuments—so we go and kill some people and then we build a monument to memorialise their death. How tragic!

When Cloud Gate, which is, let’s say, my most successful outdoor work, was first put in Millennium Park in Chicago, I saw thousands of people there. I thought, “|Why is it so popular?” So I decided to go there for myself. I went to Chicago and sat with the other people for two or three days. I had a strange realization, which is that it’s a whole object without joints, without anything that gives it scale. So when you’re up close to it, it’s a really big thing. But you don’t have to step so far away from it, especially in Chicago, where there are huge optics all around, for it to suddenly change scale. It does this expansion and contraction on its own, which is very odd, very mysterious. To me, it felt as if that saved it.

One other thing to say about it is that it was put there before the selfie, so it’s kind of a weird selfie object that was there before the selfie. I was there a few years ago, and I was told that 200 million people visited it. This was nearly 10 years ago, so it’s way more than that by now. And for 200 million people to visit, that would have meant 500 million selfies. It’s kind of funny, but it’s also interesting, this idea of engaging yourself in the process.

TS: Given your immense influence, it’s undeniable that both the formal and the conceptual aspects of your practice have inspired many other artists. But for the average individual who encounters your artwork, but doesn’t understand the full impact of your contributions to the art world, what would you like them to know about you?

AK: Oh my God. Look, it’s not for me to say whether I Inspire artists—I couldn’t say. We live in a time of huge crisis across the world, confusion, politically and psychologically, about where our culture stands. Is it enough for artists to draw on their ethnic, social, or racial backgrounds? And has that been the centre of our activity?As human beings, we’re much more complex than that. I’ve always refused to be an Indian artist, just to be clear about that. I’m an artist and I’m Indian. It’s a big part of my aesthetic world, but it is not the thing that defines me. In the age of the individual, it’s so important to hold clearly to the role that the artist plays—the curious, naughty role, in cultural practice. So in order to know more about me as an artist? You need to go and look at my stuff. What can I say?

TS: Can you say more about this role that you believe the artist plays?

AK: An artist, today and historically, has always been a figure who at some level refuses to play the game. There’s a certain level of disobedience. I find that very, very important. So if we artists only follow the conditions of capitalism, or the market, in other words, I think we’re done for. So the artist must occupy this strange space, a bit like a peace division and at the same time a space of disobedience. I deeply believe that we’re not givers of more or less meaningful messages. Our role as artists is to look at what’s half known, what’s mostly not understood. So if there’s advice I would want to give, it’s to disobey, disavow, disagree. I have that written on my studio wall. I find it very important.

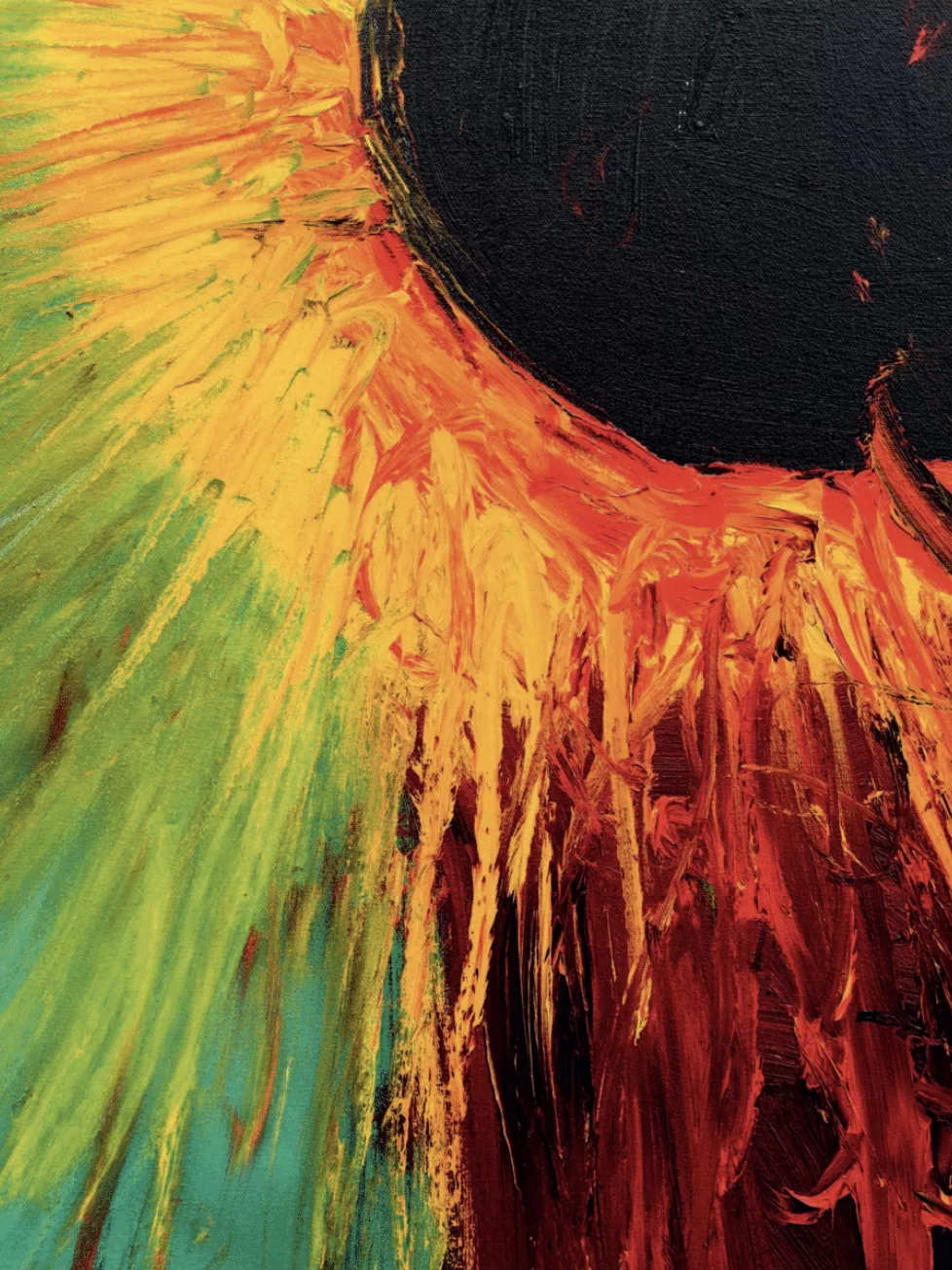

TS: Critics often focus on the engineering and the site-specificity of your sculptures. Yet, within your painting practice, there’s a softness. The paintings from your 2021 show at Lisson Gallery were described as “spiritual” and “ecstatic”. Do you bring a different sensibility to this medium?

AK: As I keep saying, I have nothing to say as an artist. I’ve no message to give the world. I should start by saying that I’ve been in psychoanalysis for 40 years. A long time. Part of that process is allowing oneself to tumble into whatever the issue is at the time.

Astoundingly, it’s a recurring theme. It happens and then it happens again and again and again and again. It’s much the same with the work of an artist. That is to say, there are certain issues that arise, whether you want them there or not, if you really follow your practice. So that’s the key: a practice.

I go to the studio every day. I try to engage fully and properly and I tell myself to make a work every day. At least one. Whether it’s a good one or not, that’s another matter. Out of practice, things emerge, issues emerge. They’re always the same issues, more or less. One of the things I think I’ve discovered is that objects are not objects. Objects don’t have just object reality. There’s always something unreal about an object and that has to do with me or us, the viewer.

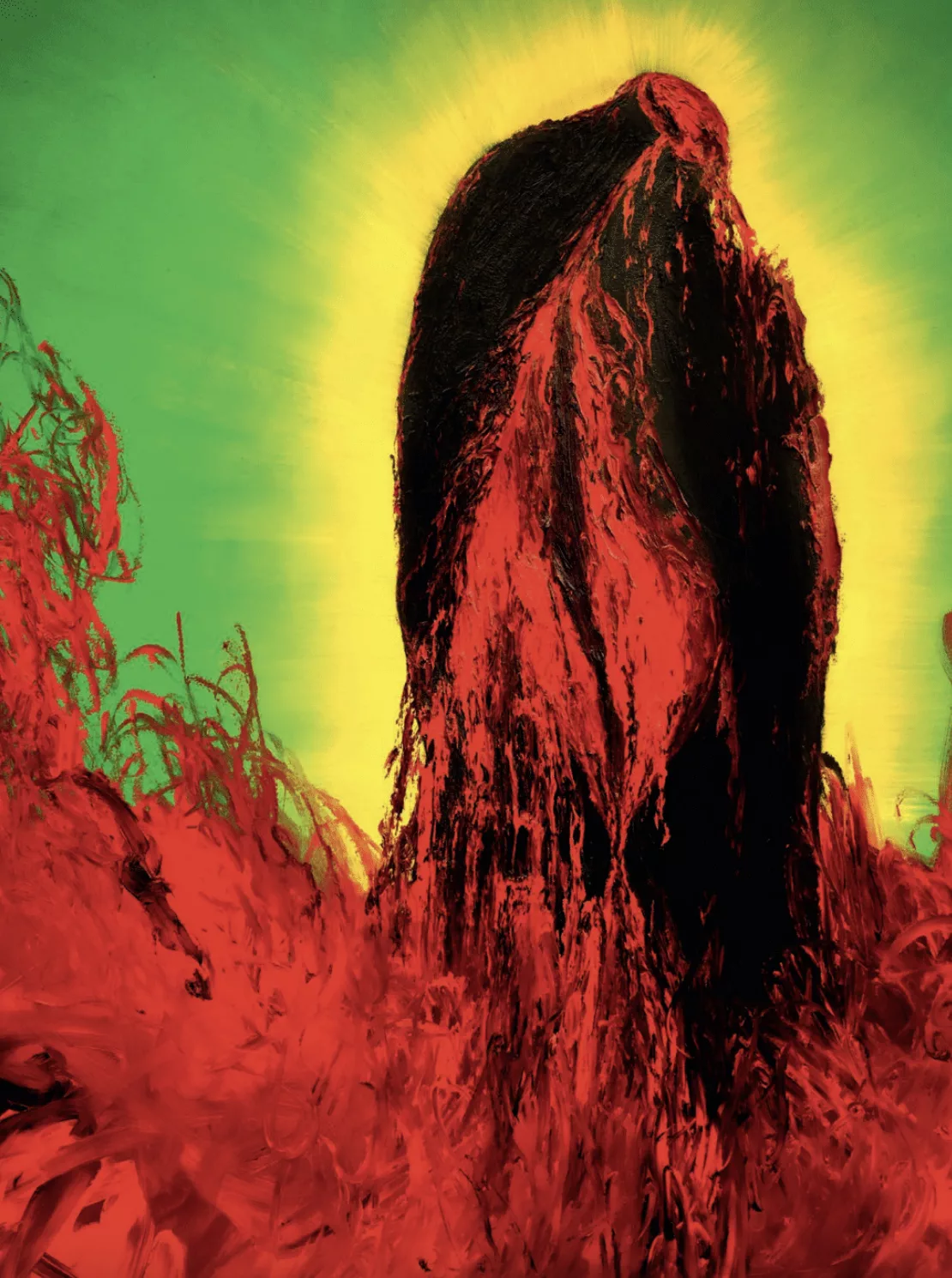

The German philosopher, Martin Heidegger has a text about how the inside of an object is bigger. Think about that. Close your eyes. There’s a kind of darkness, but it’s much bigger than your self. Look at the inside of a pot, a simple pot. That dark space, it’s much bigger than the pot itself. I’ve made lots and lots and lots of works that have emptied insides, which are bigger. They’re vacant and occupy a huge space.

The other important notion is from Immanuel Kant, who talks about the sublime. This strange thing that we know as the Sublime is terrifying. It’s not just aesthetically pleasing. It’s at the edge ofwhere I can be, of where I lose myself. This dark space, this space that’s bigger, is poetically, psychically terrifying. So in my engagement with objects, I’ve often filled that space either with darkness or with a mirror, because all the mirror pieces I’ve made are concave so it’s not an empty space, but it’s a space full of mirrors. In my paintings, I often refer to this dark, bodily interior. Whether it’s sexual or ephemeral, it’s to do with death. So all this stuff is filled in with the possibilities that the void object gives.

TS: Do you see yourself as an inventor? And how important do you believe the idea of innovation should be to an artist?

AK: Do I see myself as an inventor? Not particularly. There is, of course, a very practical thing about making sculpture. Sculpture is a long process that requires a certain level of engineering. I’m trying to engage with it in a very rigorous physical way. The stainless-steel works I’ve made over the years, they demand perfection. These objects are mirror-polished objects, which are convex, solid forms. Concavity, polished concave forms, have been around in science since the eighteenth century. Concavity is very curious because a convex object reduces the scale of all images: everything gets smaller in the reflection; a concave object magnifies the scale. It’s very hard to make a solid form in mirror polish. But to make a negative form in mirror polish is impossibly hard. You’ve got to be so perfect because every little scratch or mark will show up. So often, I’ll work with fabricators and it can take over three years to try to get them to understand and see the issues at hand. It’s a difficult process. It becomes a huge technical feat that I can’t overestimate. So from the bottom of my heart, I have to thank those three or four people in the world who’ve been able to understand this work with me.

TS: In regard to the void, can you speak a little bit about your collaboration with Surrey Nanosystems in regard to creating the Vantablack substance and your use of it within your artistic practice?

AK: I read an article in the newspaper, which must’ve been nearly 15 years ago, saying that this gentleman had discovered the blackest material in the universe. I think, “Blackest material in the universe? Wow, fabulous!” The claim is that it’s blacker than a black hole. That’s not a small claim.

I don’t know how, but I got his address. I wrote to him and said, “Will you work with me?” And he responded, “No, this is developed for defence technology, for science, it has nothing to do with art.” I asked him if we could meet, we did, and we talked and, bless him, Ben Jensen is his name—Ben agreed to work with me.

It’s not a paint, it’s highly technological. It’s a surface that’s put on an object, which is then put into something called a reactor. I still don’t know what that is—I’m not allowed to. Then what happens at a nano level, an incontestable level, is that the particles lying flat on the surface, stand up. What happens is that light that enters gets trapped between the particles that are standing up and get turned into heat and only 0.02% of the light escapes back out.

Let me put this into context. In the Renaissance, there were two great discoveries. One is perspective, which I believe probably had Islamic origins. The other is the fold. Think of all those early Renaissance paintings, all the bodies that were covered in huge volumes of fabric and, of course, folds. What is this fold? It’s obviously about being. It’s about the symbolic representation of the body. Amazingly, when you put this black material on a fold, you can’t see the fold. My contention is that this material, used in the right way, takes the object beyond being. So what it does is, it pushes the object into a four-dimensional space, not a three-dimensional space. The practice of an artist is not about the making of objects. It’s more mythological than the making of objects. Part of the mythology is that it takes the object beyond being.

TS: I love your way of describing it as bringing the object into the fourth dimension. I think that’s really interesting. I’ve never heard it described that way before.

I have a question, just out of my own curiosity, because of your relationship to technology. Do you have any interest in using AI or working with AI in the future?

AK: AI I find very, very confusing at the moment. It seems to me that it’s a tool for the commercialisation of objects. I think as artists we need to be extremely suspicious of it. It’s yet another commercialization or capitalist occupation of the things that artists struggle to uncover.

TS: You once said, “It’s as if the collective will come up with something that has resonance on an individual level and so becomes Mythic.” Personally, I find your sculptures to be material-centred yet ethereal, which is an unexpected combination, yet mysticism which you’ve spoken about before and even today in this interview, has a connection through materials to spirituality or to that which is transcendent. What is your relationship, if any, to mysticism?

AK: Let me put it this way. Paul Valéry, the great French poet, said that a bad poem is one that falls into meaning. A good poem is one that sits in a strange limbo between meaning and no meaning. It’s this strange space of half meaning, of almost meaning, a mysticism. We’re talking about the poetic spirit, the poetic part of ourselves that we can’t quite grasp. And I think it’s the place of great art. It seems to me that we live in a world of known objects. Every single thing has got a name. There are only two or three places where there are unknown objects or notions. One of them has to be up in the physical cosmos. The other is in art—when there are moments of: what is that? Is it art? Why is it art? Then the other place is within ourselves: there are bits of us that we can’t quite grapple with, can’t quite know.

What a wonderful thing to do: spend a lifetime trying to make something that nobody can name!