I’ve been a mum for over 20 years. It defines me: caring, entertaining, being driven nuts, laughing with and worrying about my children. I had my first baby in my twenties at the tail end of the ladette and YBA era (crop top with a pregnancy bump? Yes I did.) The ideal then was that kids shouldn’t change you: you’d given birth but you could still party, prop up the bar, affect ironic detachment and a spiky carapace.

It didn’t feel like there was cultural space in that art world for maternal softness, to enjoy loving a child, to feel agoraphobic, to allow yourself not to be in control of everything. Imagine that: What a bore you’d become! I remember a friend saying that I was the only woman in our circle who spoke about her children as if she actually liked them. In retrospect the pose we were trying for was deadbeat dad.

Few female artist friends of my generation had kids: they felt they would not be taken seriously. Those who did tended to keep the two spheres separate: they’d make up dry excuses rather than admit a PTA meeting or lack of babysitter. There were brave women who demanded the space to be both, but they were few (Laura Ford, I salute you.) This has started to change: I’ve loved watching the new generation of artist mothers asserting the interconnectedness of their lives, and requesting space and consideration.

“Few female artist friends of my generation had kids: they felt they would not be taken seriously”

Even as a writer, my experience of being a (for a good while, single,) mum in the art world was not great: for many years I couldn’t go to evening openings; I couldn’t travel to overseas shows and biennales; I couldn’t go on press trips. All these were routine for male colleagues: it was how they gathered information, discovered new artists, networked and advanced themselves. The current art world is tough for anyone with caregiving responsibilities.

I discussed this with Dr Kate MacMillan—artist, academic, mother, and author of the recent Freelands Foundation Reports into the Representation of Female Artists in Britain. There have been great initiatives around the world charting gender imbalance, but few seemed to be asking what impact motherhood had. Earlier this year, I interviewed 50 artist mothers, and my findings have been published in an essay—Full, Messy & Beautiful—alongside her report this year.

Below, 12 of those interviewees share their experience of being an artist mother, as well as some of their work.

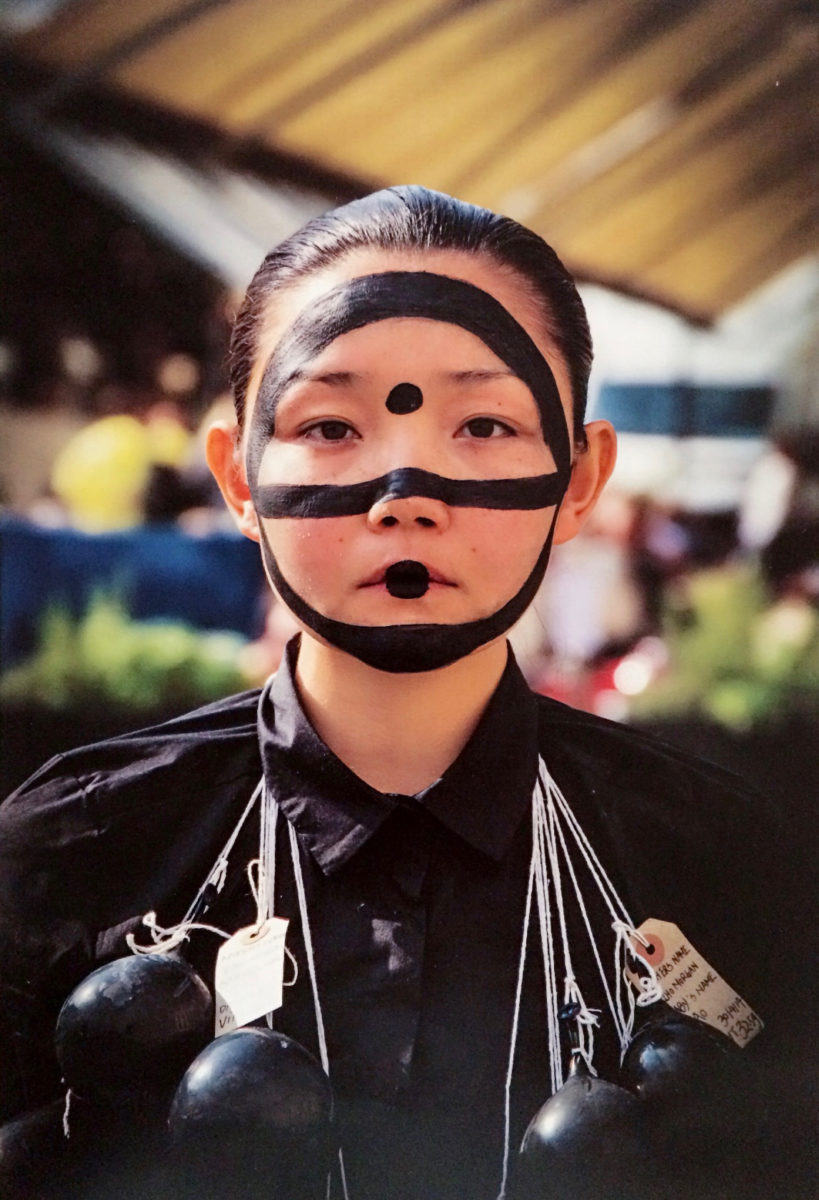

- Xie Rong, Evil Mother Gothenburg, 2016 (left); Touching Happiness, Guangzhou, 2014 (right). Courtesy the artist

Xie Rong, London, performance artist, two children aged 6 and 4 half

“When I first found out I was pregnant, two of my international performances got cancelled. Both curators were actually female but without children. They both emailed me and said: ‘Good luck with the family life, if you ever decide to perform again in the future please keep me informed.’ I was shocked and very upset. Motherhood is tough. I first fed my son after 30 hours in labour and an emergency C-section. My body was so alien to me and in great deal of pain: I don’t think any text or wisdom can prepare a girl to become a mother.

As an artist it allows me to translate that strangeness and multi-layered emotions into action and visual language. My body is very present in my work. It was almost a childlike body. After two kids, my image changed. There aren’t many performing mothers, I found it very hard to be included in popular gender politics shows and I dislike exhibitions that only focus on motherhood and childbirth.”

Samar F. Zia, London, artist, two children aged 6 and 3

“There is no time. The struggle is unbelievable. If I did produce work in the last few years, it was at the cost of my sleep and health. You just eat into your free time with your spouse, sleep, meal times, and other odd pockets of time to do a minuscule amount of work, because most art is time and labour-intensive.

I still managed to do a weekend residency when I had one child, for a few months at a stretch, so was able to start on a decent body of work that I completed in my own time, but with two young children it is absolutely impossible.

“If I did produce work in the last few years, it was at the cost of my sleep and health”

It isn’t practical to set out a little space at home and then pack it up again before a child comes and helps himself to paint. At desperate points, to meet deadlines for paid projects, while my older one was in school, I arranged for a sitter to mind the little one so I could concentrate for two or three hours at a stretch. But these projects were sound and video pieces: if I was painting, the time it would take me to set up and pack up would make it impossible to actually make art and babysitting would be super costly.”

Macarena Rojas Osterling, London, artist, two children aged 6 and 2

“If we like it or not, our priorities change. First, you obviously don’t have enough time to attend openings, screenings, talks, etcetera, so your art connections start reducing. Second, there are lots of things you cannot do anymore because you are caring for a little one: artist residencies or different grant opportunities that require you to spend time in situ somewhere else. And, not least at all, having the ‘artist personality flowing’—doing drugs or getting drunk and being bohemian and wild. (I was never that person, but I understand how the ‘market’ sometimes loves the idea of the artist like that.)”

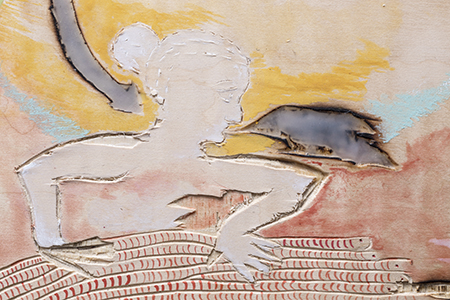

Selina Ogilvy, Somerset, artist, three children aged 16, 14 and 10

“Motherhood has every impact on the time and space I have to make work. It dictates and governs it all. However, if I allow that to happen—to be a little more selfish, or perhaps a better way of putting it, to put creativity first—then I have actually found that improves one’s motherhood. The reason is simple and has taken many years for me to realise. If I am more creative, I am happier, home is happier (and messier so therefore not quite so functional), my mother role is better, the children are happier.

If I have not been creative and think that my duty is to put all chores and practical jobs first—the tidying, the decorating, fixing the washing machine, making a proper kitchen, the sorting, the bills, the kids – it works for a while but then frustration builds up, I have a meltdown and motherhood goes downhill. If I treat creativity like a job, therefore it is work that must be done: that creativity makes me happier. The children also then understand this and respect it.

As for the home being a functioning space? Well, something has to give. A GP once said to me you have to treat the patient as a whole not just part of them. The whole artist needs to be nurtured and not just part of them. Being a mother comes first, but I was always an artist.”

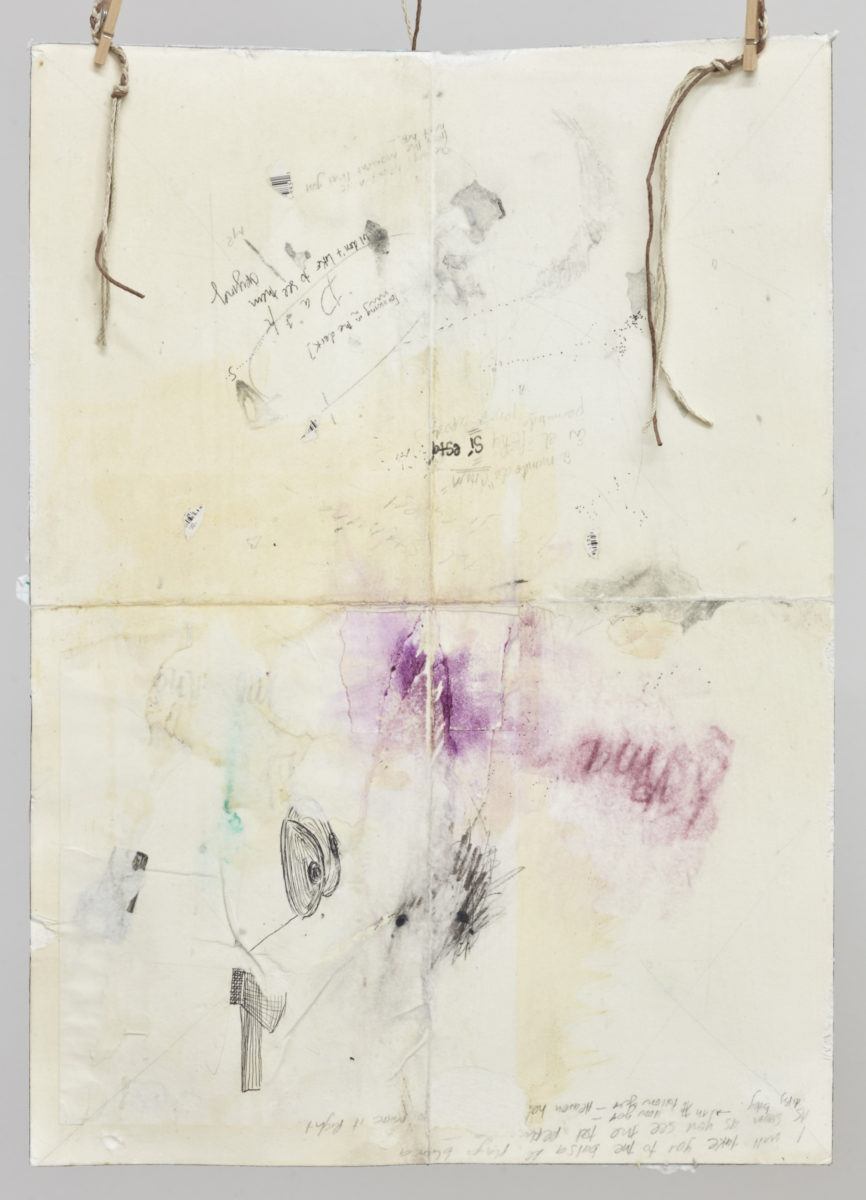

- Courtesy Gaia Fugazza

Gaia Fugazza, London, artist, two children ages 6 and 8

“I feel motherhood has a very specific impact on artists compared to other professions. Motherhood is very creative and inspiring. An artist can decide what their work is and thus allow accommodating for changes brought by motherhood. So in this sense it is great to be an artist mother while it can be very challenging economically. The majority of young artists can’t support themselves through their work, let alone support a family, so they have other jobs.

If you do exhibitions but don’t have a very strong gallery behind you, you probably can’t afford childcare to do shows, so really you can work as an artist and have children only if you are wealthy to start with, or something other than your artistic practice is paying for them. All of this will cause you to either neglect your practice or to be dependant on someone else to have a bit of space to do your work. This will make you experience your practice not as viable work but as a luxury.

“The majority of young artists can’t support themselves through their work, let alone support a family”

So you will be looked at as a mother that doesn’t look after her children properly to do a job that is unpaid that only benefits her own glory. You may keep fighting and you may succeed in being able to support yourself with your practice, your work may be recognised as important, but there will be lots of shame and blame along the way and a lot of mothers will give up. This is what I have unwillingly experienced and fought against.”

Cecile Johnson Soliz, Cardiff, artist and educator, two children age 21 and 20

“Motherhood needs the same sustained time that studio artwork needs. Each, for me, needs psychic, emotional and physical energy. Being open and consistently engaged in these are important to sustain any real commitment. Once a mother I had less time, energy and ability to sustain an intense studio practise: it altered the long days I had in the studio and I worked in between family-life needs. To treat artists all the same—as being available to produce 10-12 hours or more per day—is a mistake. Because of this we all miss out on what women artists have to offer.

The art world’s lack of acknowledgement, understanding and celebration of motherhood had a far-reaching impact on me. Like many of my friends, I chose not to be a young mother because of it. I was serious about being an artist and I wanted to be taken seriously. But it is sad that more opportunities for a woman artist who was a mother were not available, and that there were not better models of that accepted within the culture. My son told me more than once that my art is a ‘hobby’. Where in his education has he seen any images or TV programmes of mothers who are artists and appreciated for being so?”

Joanne Masding, Birmingham, artist, one child aged 18 months

“I don’t know what opportunities I might have missed out on because of a presumption that I couldn’t or wouldn’t want to be involved because it wouldn’t marry with family life, but I know that I’ve never been asked how an invitation might be adapted to suit my individual circumstances. I’ve written applications to Arts Council England in the past, and have asked to add childcare costs as a budget line. This is not permitted and should be accounted for within artist fees.

“Any ways of acknowledging that being an artist also includes being a human would be welcome”

I wonder why I need to disguise this legitimate cost of working, that falls mainly to women in the form of unpaid labour, rather than accounting for it openly? To me, hiding it contributes to the disparity between the sexes, the extent to which caring roles are seen as unimportant, and that having children is a lifestyle choice that you must bear alone.

Any ways of acknowledging that being an artist also includes being a human—and that might mean being a mother, a carer, someone with a variety of needs and individual circumstances—would be welcome, whether through budget lines, or just more open questions, conversations and time for one another.”

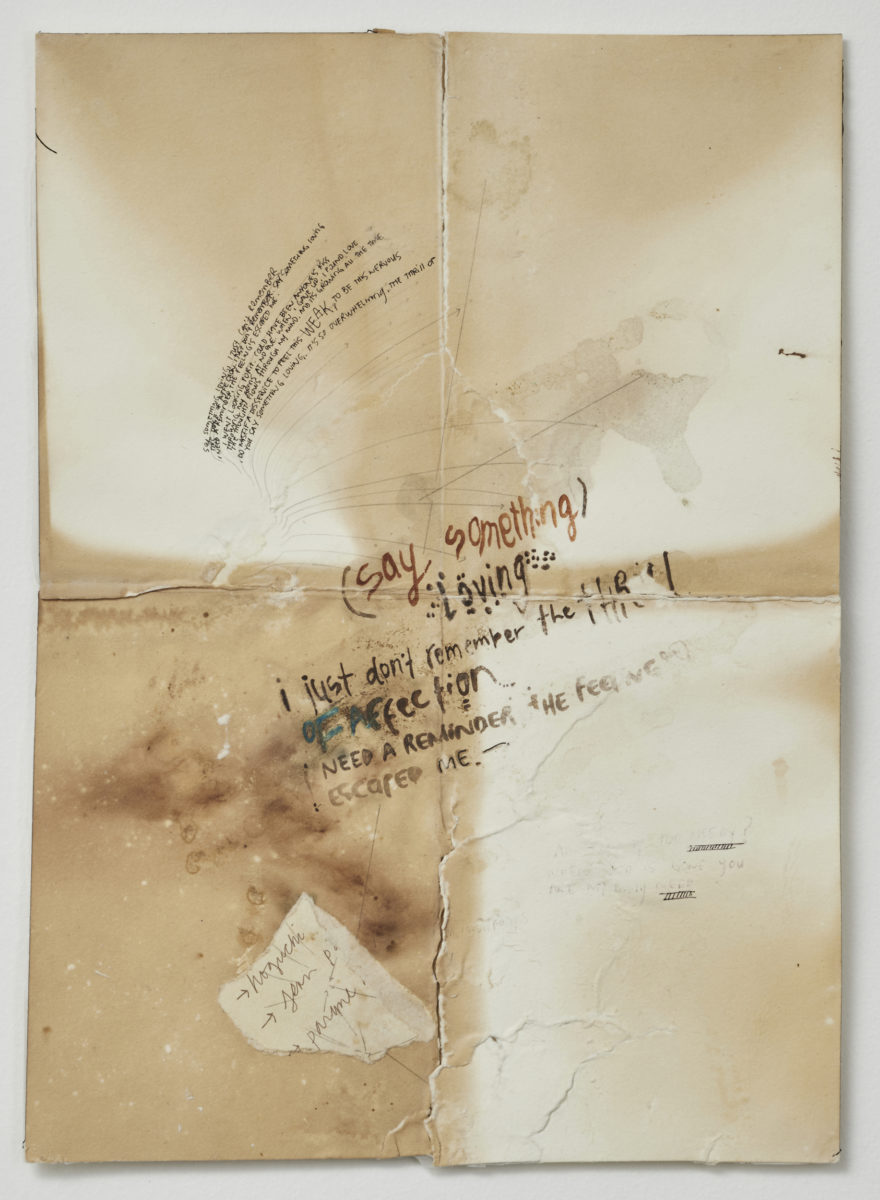

- Rosalind Faram, Belters, 2020 (left); Catisfaction, 2020 (right)

Rosalind Faram, West Sussex, artist, four children aged 29, 23, 18 and 15

“I had naively believed that I could just put the baby in the pram and she would sleep when she was meant to and I could paint. The reality was that I was cut off from my friends, traumatised by the birth, she screamed all the time, I had post natal depression but didn’t get help, then she became ill with severe eczema and we lived in hospital for weeks. I gave up any hope of having a career as an artist but lived with the identification of it. I recall someone asking me what I ‘did’ and I said ‘I’m an artist’, and they said ‘How can you be an artist when you don’t make anything and you don’t sell the things you don’t make?’

It is not just becoming a mother that affected my artistic life—I could have had a supportive partner and parents or parents-in-law, and I could’ve continued to make work and build a career with a relatively small gap as a lot of women do. But there were many other elements—social, economic, health that undermined my possibility of doing that. My work as an artist does not bring in money and therefore is not regarded as a priority (understandably). It is viewed more like ‘something Mum must do’, rather like an obsessive hobby that should be put aside when they need my maternal ‘services’.”

Paula MacArthur, Kent/Sussex border, artist, two children aged 23 and 24

“At art school I remember being told ‘don’t marry a painter’ as he would be too much competition for me and that I’d have to choose between a career or a family—that was back in the late 1980s. One tutor at the Royal Academy told me she’d decided to choose the career option. She was successful—a Royal Academician no less, when there were very few female RAs—but she was single and regretted not having a family hugely. That was an important conversation for me, and back then there was a sense that you could be a superwoman and have it all.”

Ingrid Berthon-Moine, London, artist, one child aged 14

“I’ve realised that working from home made me work on a smaller scale; the work was domesticated in this way. Working in the living room or in the kitchen, doing things fast and tidying up faster in order not to leave hazardous goods or too much mess: I think it’s impacted the whole process. Since I have been able to have a studio, I’ve worked on bigger pieces and when there is a show coming, the mess I make is incredible but I can leave it like that.

“We are talking about space and time but the unquantifiable maternal guilt was (and still is) a huge burden”

We are talking about space and time but the unquantifiable maternal guilt was (and still is) a huge burden. Chatting to some other artist mums, we tend to all feel the same: that’s a common denominator. I’ve seen some father artists (why does it sound weird to read that about male artists?!) going on residencies on the other side of the world and they didn’t seem to think twice about going. I would be devoured by guilt but I do envy their guiltfreeness.”

Sarah Kogan, London, artist, one child aged 16

“My work has continued to adapt to the time and space that I could give it. I had problems having a child and have taken nothing for granted, so wanted to both be at home when needed and also maintain my work. This balance is not a fluid, easy, organic process in some kind of ‘mother earth’ fantasy. It comes through a series of managed steps, early hours and really hard work.

I think that female artists are often loath to be seen as the partner of someone or the mother of a child, in terms of their careers. There is a sense that we will be diminished as professionals if our relationships with our families become a focus within our visible lives in the art world. There is awareness that we do not want to be seen through a domestic lens.

The history of art is so steeped in the sexualised perception of women. It is almost as if we are seen through that prism until we become mothers and then we are seen as domestic objects of little interest. I think there is a conscious effort to overcome that perception by operating externally as an individual outside of the family arena. This compartmentalisation is an art form in itself and can be conflicted.”

Maureen Nathan, Dorset, artist and educator, four children aged 44, 42, 30 and 27

“In the early 1990s a shift seemed to occur in society generally that trickled down to women artists who happened to be mothers. This may have had something to do with teachers, like Phyllida Barlow, and others who were themselves artist mothers making space in artists’ practice for the acknowledgement of parenting responsibilities. My art practice in the last 25 years has been far different to the previous 15 or 20—and in both instances I had parental duties.

A general acknowledgment of a woman’s right to a career and life of her own alongside motherhood fed into my own practice. This external validation gave me the confidence to choose studio time over housework or other domestic responsibilities and opened up my partner’s and my children’s minds to the idea that I had an internal life manifested in my artwork equal to any other practice or profession.”

Hettie Judah, Full, Messy and Beautiful

Published as part of the Freelands Foundation report The Representation of Female Artists in Britain During 2019

READ NOW