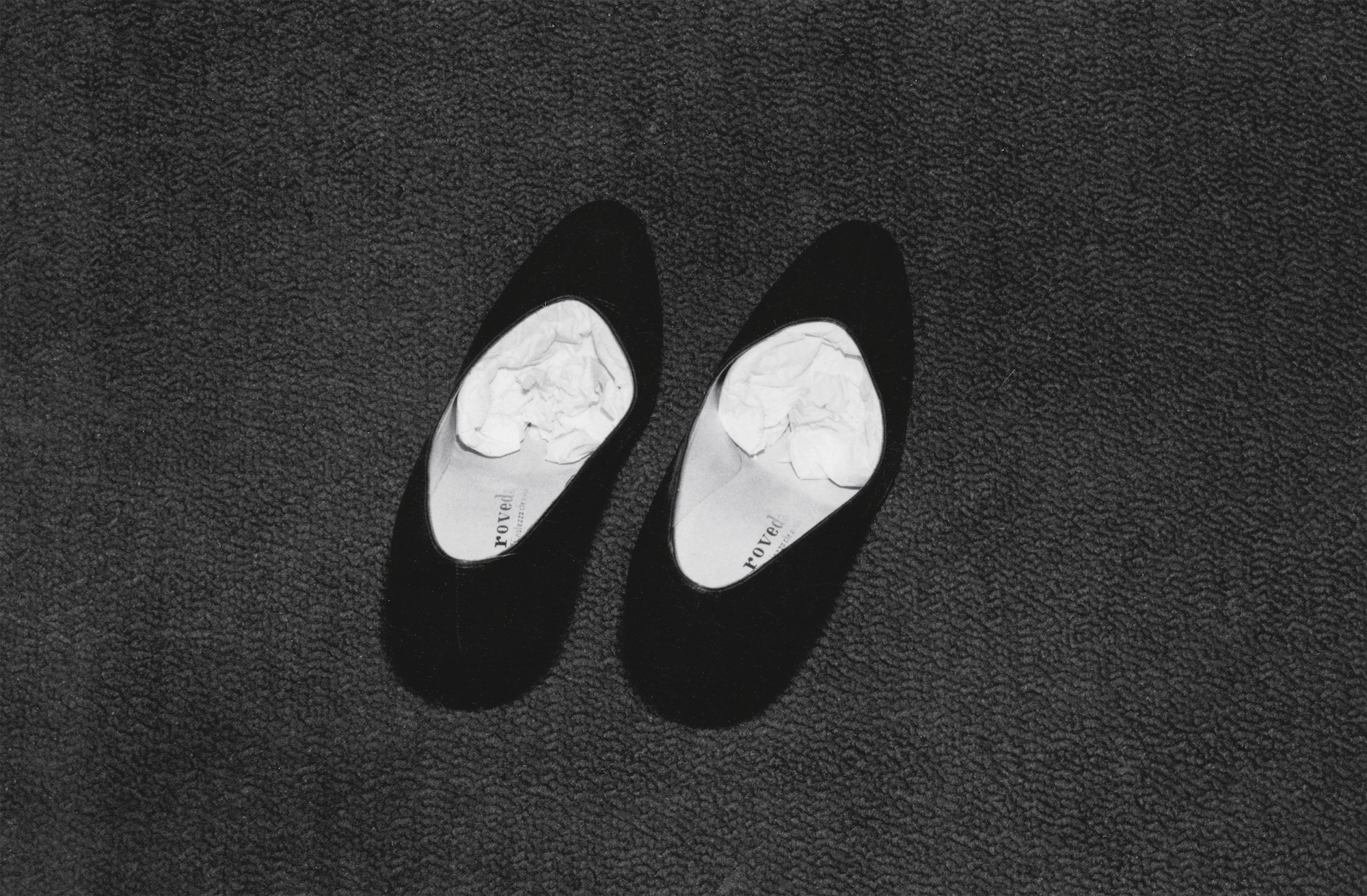

Detail from “Room 25” in The Hotel by Sophie Calle, 2021. Siglio

Sophie Calle has a long history of photographic voyeurism. It started in Paris in 1979, when she invited strangers to sleep in her bed: men and women, naked and sprawled, often asleep but sometimes awake and looking Calle in the eyes. That same year, she travelled to Venice in pursuit of a man she’d met at a party, phoned hundreds of hotels until she found out where he was staying and then shadowed him through the winding side streets.

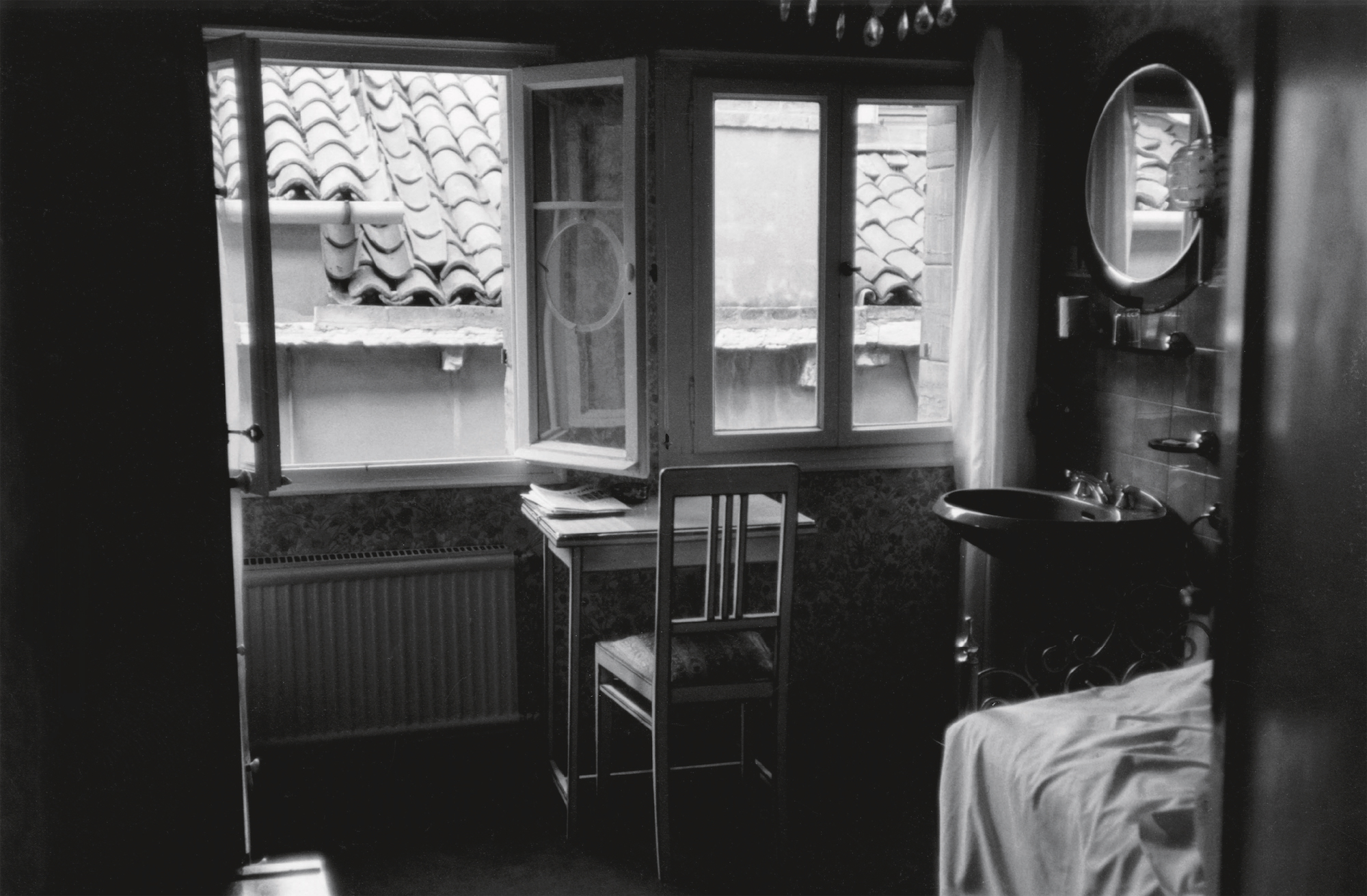

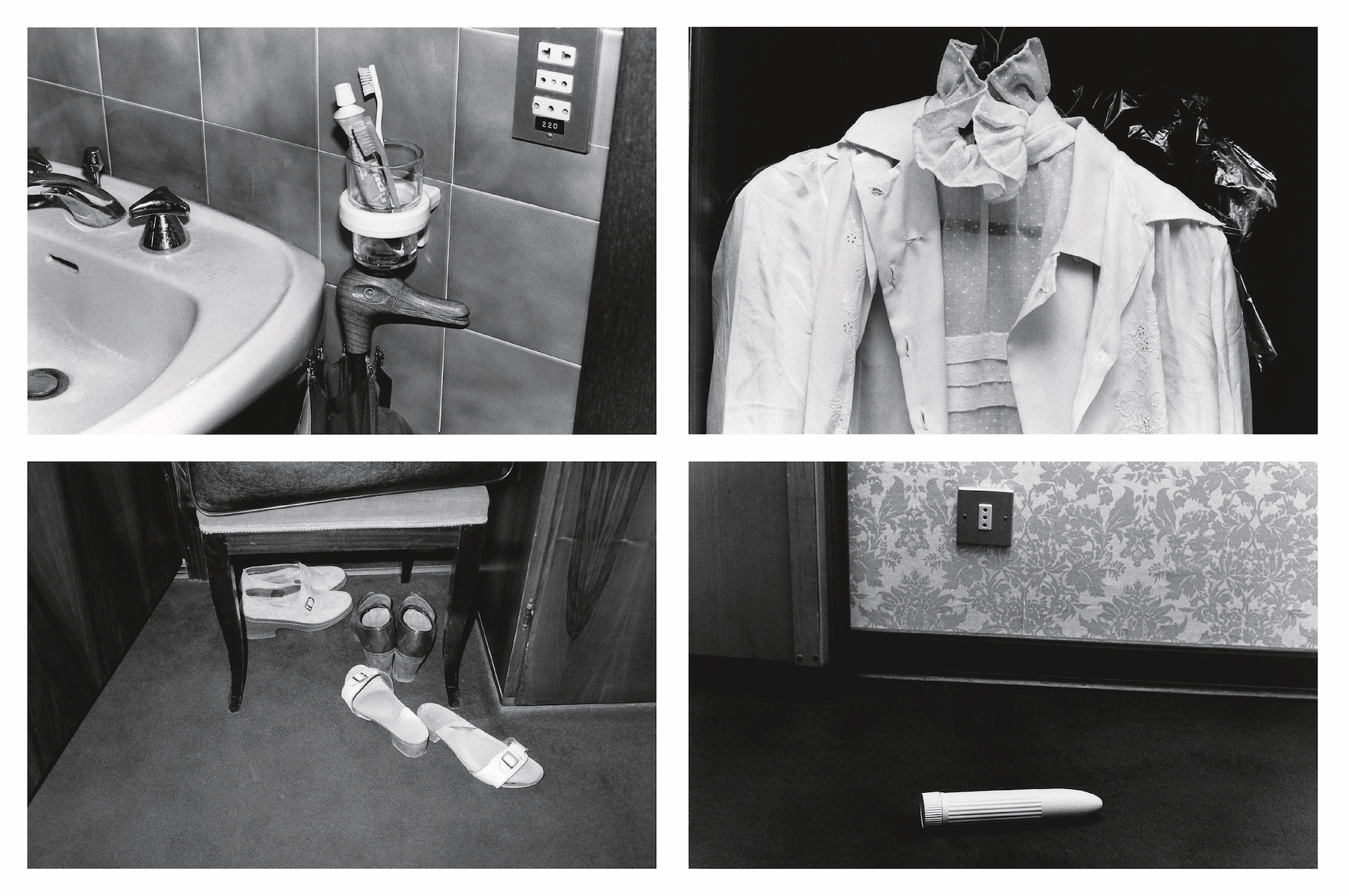

It was also in Venice, in 1981, that she embarked on another project probing the spaces between us. She took up a temporary job as a chambermaid at “Hotel C.”, but played detective. With a camera and tape-recorder stashed inside her mop bucket, she forensically catalogued what she found in wallets, within vanity cases and under pillows.

The resulting image-text pairings (Calle’s trademark) were published in The Hotel, now getting its first standalone English edition. They are meticulously arranged by room, date and time, and bound within a cover graced by decadent wallpaper designs. This book-cum-quest strikes the quintessential Calle-chord: its through line is the longing to know the lives of strangers.

Predictably, Calle’s images are not short of the banal: dirty panties, postcards, porn magazines, carnival costumes and arbitrarily-lined shoes. Yet there is a tense pleasure in being pressed close to Calle’s mind, with its fluctuations between clinical detachment and rawness of feeling. “He has left his orange peels in the wastebasket, three fresh eggs on the windowsill and the remains of a croissant which I polish off,” Calle reports alongside a shot of said bin. “I shall miss him.”

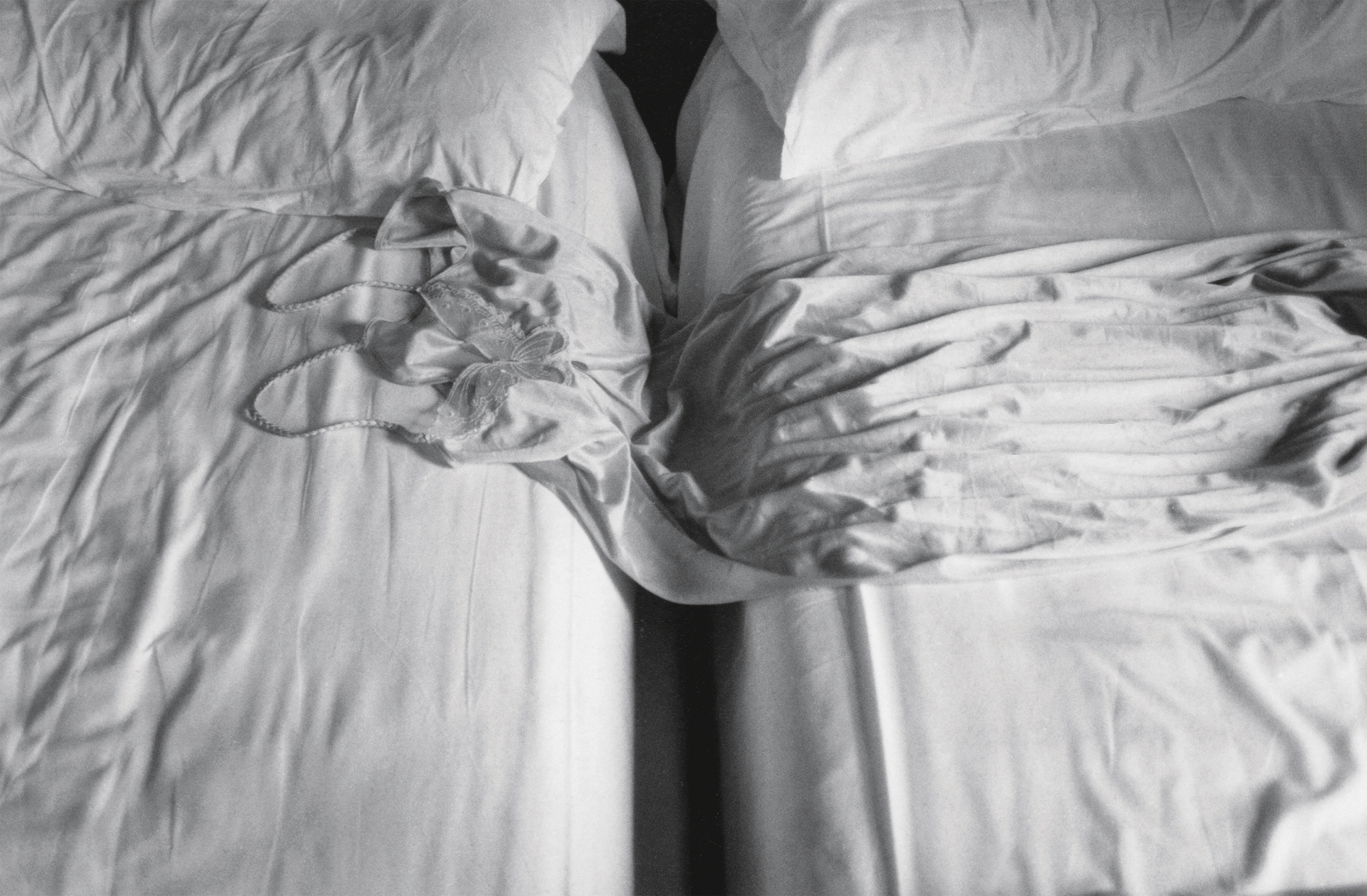

Equally thrilling is seeing this world through Calle’s eagle eyes, which keenly track the day-to-day migrations of objects (even if there is actually little movement: “Nothing has changed,” she feels obliged to relay). Beds are at the centre of Calle’s focus each entry commencing with a notation of who slept in which side of the bed, whether they’ve made it or not, and how many pillows they used.

“Calle forensically catalogued what she found in wallets, within vanity cases and under pillows”

The veracity of Calle’s entries may sometimes be up for debate (the lovemaking she painstakingly narrates from next door, for instance), but there’s no escaping the iffy ethics in plundering real lives for art’s sake. Even by today’s standards, when voyeurism is deeply embedded into our internet culture, Calle’s dismissals of privacy are hair-raising. Dunked into the detritus of their belongings, it can be easy for us to forget that the guests have real lives and, even more crucially, that Calle’s actions may have real life consequences.

On Friday 6 March, the key turns in the lock while Calle is perusing a guest’s diary. She manages to throw it into the suitcase, but upon sheepishly exiting the room, she realises she left the suitcase unzipped. Minutes later, Calle is ordered to clean the room because the guests have checked out. “Did I play a part in causing this departure?” she wonders. Any sense of guilt, though, expired later that morning: “In two hours, I will follow them.”

“Even by today’s standards, when voyeurism is deeply embedded into internet culture, Calle’s dismissals of privacy are hair-raising”

Thirty years after her chambermaid stint, Calle flipped the script. Checking into a luxury suite in Madison Avenue’s Lowell Hotel, she kindly invited New Yorkers to pay her a visit, and they did. Affixed to her door, however, was a note: “If the sign reads ‘Do Not Disturb’ at the time of your visit, please respect it and ring the bell to indicate your presence.” Rich, perhaps, considering the extent of Calle’s invasions in Venice.

However, even back in 1981, Calle had lines she didn’t cross. Room 45’s “Do Not Disturb” sign forbids her entry for nearly a week. After days spent peeking through the keyhole (“darkness”) and sticking her ear against the door (“silence”), Calle is finally granted entry. In the bedsheets, she discovers a lobster claw.

Calle’s stories constitute a radical intimacy, attempting to master not only the art of snooping, but of losing too. Reminders of mortality linger on each page, and it’s hard to ignore the pallor of the place: a transient terrain in which people come and go, like life itself. It feels as though Calle, with her keen, conceptual rigour, was acutely aware of this too: the power of the hotel as both medium and metaphor.

The most moving moment of The Hotel arrives during Calle’s inspection of Room 30. Brilliantly piecing together a series of clues (a wedding photograph, an old bill for the same room and a never-worn nightgown, laid out on a chair beside the double bed), Calle concludes: “Exactly two years ago, M.L. spent the night in Hotel C. with his wife. He has come back alone. With the embroidered nightgown in his suitcase.” She signs out with a promise: “I’ll do the room later.” You find yourself hoping that she never does.

Alessandro Merola is assistant editor at 1000 Words

All images courtesy the artist and Siglio