In Christmas 1963, future filmmaker Bruce Bickford saw something on TV that changed the course of his life. “A commercial had Santa Claus riding on the floating heads of a Norelco shaver,” he recalled in an interview. “I wanted to recreate that kind of image.” A peculiar reason to embark on a career? Maybe, but it is as nothing next to the strangeness of the work that trajectory yielded…

Bickford (1947-2019) never achieved much in the way of mainstream success, but he is acknowledged by connoisseurs as a pioneer of “claymation”, a blend of conventional animation alongside sets and figures fashioned from clay. Lovingly crafted and laboriously realised, Bickford said it could take about five weeks to create 40 seconds of usable footage. The critic Steven Puchalski described Bickford’s work as “remarkably complex” on a technical level, but “on a psychological level, it’s just plain fucked up.”

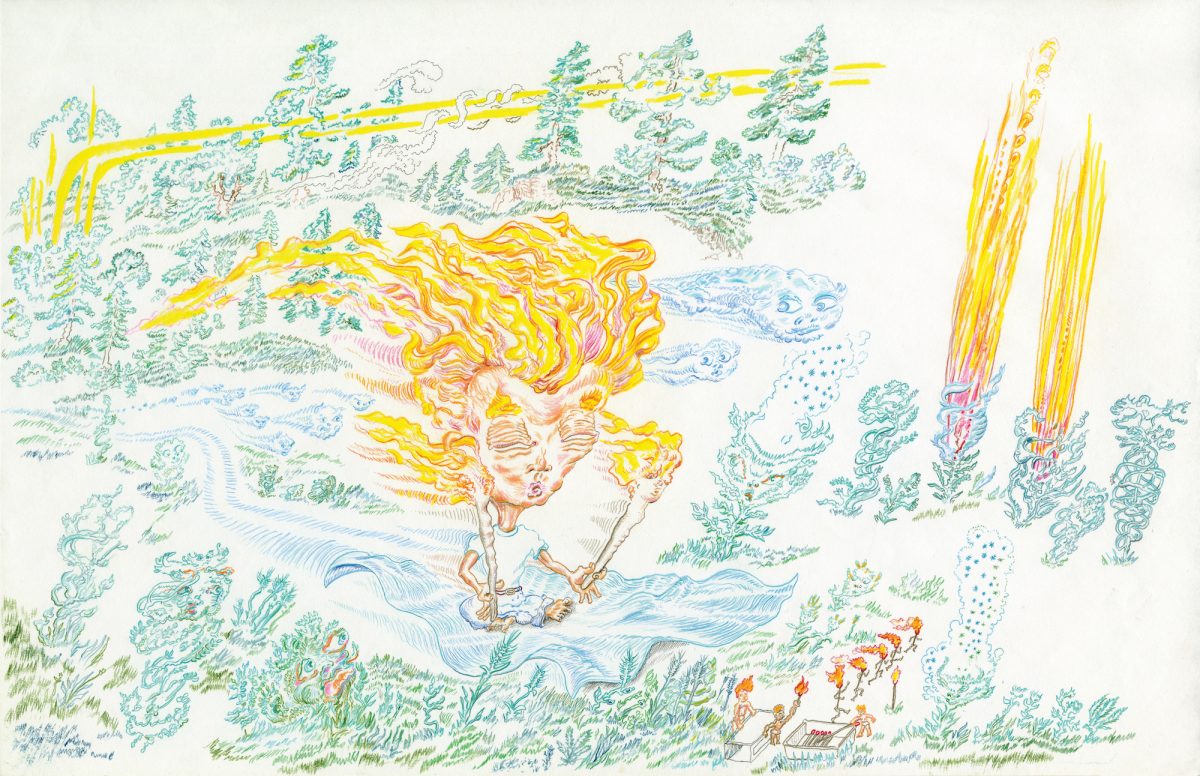

This appraisal might actually be an understatement. Bickford’s films, many of which were created to accompany the music of his long-term collaborator Frank Zappa, are by turns terrifying, visually ravishing and utterly unhinged. He created clay universes of psychedelic horror in which human bodies decompose into amorphous blobs of faecal slime, maggot-like guts spew from lacerated torsos and foliage mutates into webs of rotting tripe.

Imagine painter Hieronymus Bosch crossed with an LSD nightmare and kicked into howling motion. The choice of clay for the material lends the films an appealingly handmade, tactile quality, and leaves the viewer with the inescapable impression that they may just have wandered into the mind’s eye of a demented five-year-old. And like so much that emerged from the weirder fringes of the American counterculture in the 1970s, these curious visions had no real precedent.

“Bickford leaves the viewer with the inescapable impression that they may just have wandered into the mind’s eye of a demented five-year-old”

Yet impressive as his emergent work must have seemed at the time, it would seem that nobody really knew what to do with it. In 1969, following his return from a stint with the Marines in Vietnam, Bickford became serious about animation, using his parents’ basement to make several short films that clearly signalled the grotesque direction his vision was taking. He recalled creating a windmill that transformed into a swastika for one of these films, while in another he had Richard Nixon turning into a hippopotamus.

Attempts to shop them around to California’s animation studios proved fruitless. Hollywood, clearly, was not quite ready for a psychedelic Ray Harryhausen from hell, but they made an impression on Zappa, who offered Bickford a job as his own in-house filmmaker. The role allowed Bickford the means and space to realise his labour-intensive vision and resulted in several compilation films of his imaginings, including Baby Snakes (1979) and the violently apocalyptic The Amazing Mr Bickford (1987).

Yet at the same time, the association tethered him to the orbit of his rock star boss, under whose terms he was forced to sign away the rights to his early films and work on projects for which there was never a clear brief. “There was no, almost zero, organisation,” he recalled. “[Zappa] would come up with an idea, but there would never be any follow up.”

What Bickford wanted to do was make a feature, but Zappa’s whims ensured that his output remained piecemeal throughout the 1970s. It was not until the pair parted ways in the mid-1980s that Bickford would have the time to realise the kind of film he aspired to, the result of which is the breathtaking Prometheus’ Garden (1988).

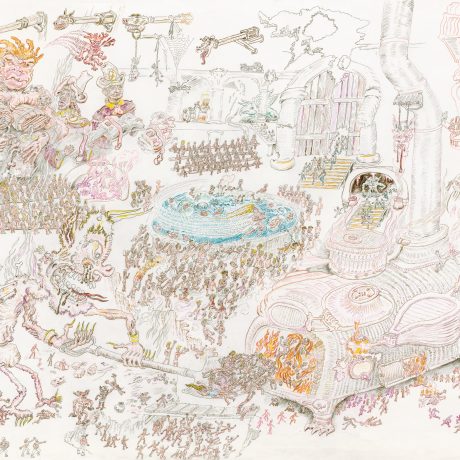

Bruce Bickford, Prometheus’ Garden (still), 1988

Seven years in the making, the film is a loose and characteristically twisted retelling of the titular character’s adventures, and came as confirmation that Bickford could translate the shock value of his gross-out shorts into long-form cinema. Even seen now, it’s a film that shocks and disturbs, but more than anything, leaves the viewer wondering what unholy place this demented vision sprang from.

“Imagine painter Hieronymus Bosch crossed with an LSD nightmare and kicked into howling motion”

He would never realise anything quite so ambitious again, and in later years devoted increasing amounts of time to working with the less-demanding medium of pen and paper. His drawings, some of which can currently be seen in a new exhibition at New York’s Andrew Edlin Gallery, may lack the kinetic splendour of his films, but still successfully distil his nightmarish imaginings into chaotic, often thrilling standalone images.

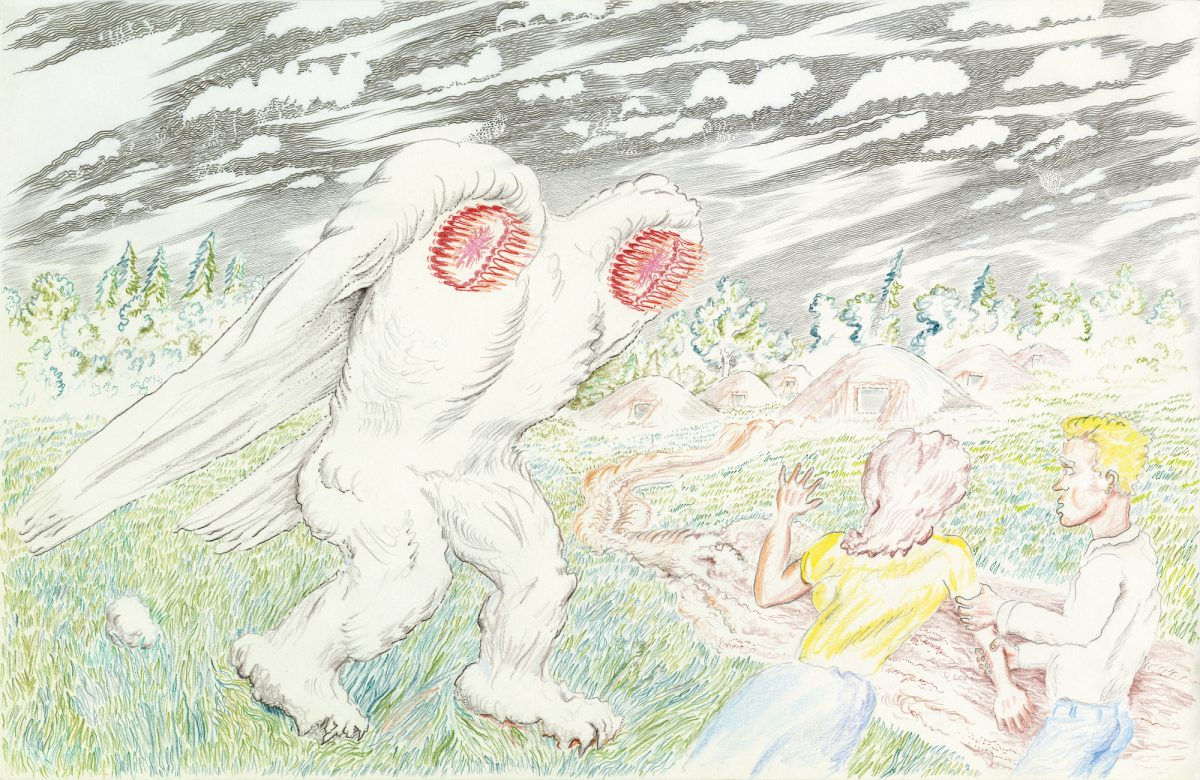

In some drawings, cacophonies of contorted faces cut free of context crowd out whole swathes of the composition. Elsewhere, animals, plants, objects and buildings are rendered in an often deliberately crude, illustrative style, which, as the show’s curators note, appears to owe a debt to the work of the Belgian proto-surrealist James Ensor.

- Untitled (Matchstick Man), c. 2015 (left). Untitled (Mothman), c. 2015 (right)

It might seem strange to discuss the work of a man who claimed an advert for shaving products as a formative influence in the context of canonical art, but it is a valid line of enquiry nonetheless. Bickford seemed genuinely unconcerned by generic categorisations, but it’s clear that he possessed an artistic sensibility in the purest sense: an obsessive drive to bring visual ideas to life, regardless of how time-consuming, physically challenging or pointless the process of doing so might outwardly appear.

It’s tempting to wonder what he might have accomplished had he been let loose at a mainstream Hollywood studio, but the limitations that he faced might, in artistic terms, have been a blessing. Right up to the end, Bickford’s work remained contingent, scatty and defiantly individual.

Digby Warde-Aldam is a Paris-based art writer for The Week magazine

All images courtesy the artist and Andrew Edlin Gallery