As Europe’s largest exhibition inaugurates its one-hundred-day presence in Athens, Andrew Spyrou takes a first look at a selection of the vast number of works located across the city, which have sought to reformulate the local geographical urban experience.

Located across over forty venues throughout the city, documenta14 has in one movement reconfigured the experience of Athens. Impossible to visit comprehensively within a few days, the exhibition welcomes an invested approach to viewing. From the first moments of the press conference–where several hundred of the artists, creators and administrators involved in documenta performed a short but moving rendition of Jani Christou’s Epicycle in the city’s main concert hall, the Megaron–it was quite clear just how enormous this event is. A hurried navigation of the city, which has somewhat defined the opening preview days, as the press desperately absorb as much as possible before their forty-eight-hour pass expires, is not a recommended method of experiencing the scale that has been accomplished here.

Across the city’s museums, libraries, workshops, cinemas, squares, parks, television and radio, amongst the other spaces and places in which documenta has a presence for the next one hundred days, visitors can adopt a position of ‘unknowing’, as the festival has itself done with its working title Learning from Athens. This attitude can allow the visitor to absorb more readily the richness and beauty both of the artworks and the city itself, sometimes layering over existing experiences of Athens, always allowing space for the unexpected and surprising.

Several institutions house the major exhibition collections, from the National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST), with all its storeys and its glorious panoramic rooftop, finally open to the public for the first time, to the Benaki Museum’s Pireos Street Annexe which hosts a branch of the documenta exhibition alongside its existing programme; and from the cavernous exhibition halls of the Athens School of Fine Arts, a former textile factory, to the hauntingly incomplete brutalist concrete structures of the Athens Conservatoire.

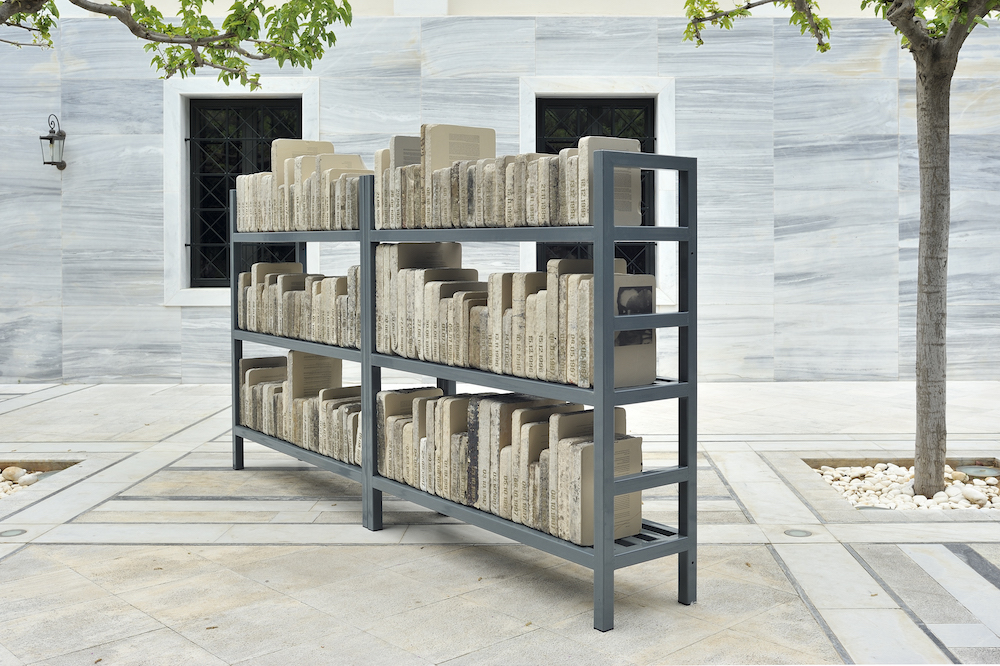

But it is likely to be the less-prominent venues that will inspire the most excitement. The peaceful Gennadius Library of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, in the smart Kolonaki neighbourhood, hosts in its manicured gardens a foreboding library of its own: Gurbet’s Diary, an artwork by Banu Cennetoğlu made up of slabs of lithographic limestone, stacked on shelves like books, each containing the text of a now-banned diary written between 1995 and 1997 by Gurbetelli Ersŭz, a Kurdish journalist and former Editor-in-Chief of Ozgŭr Gŭndem, a Turkish newspaper known for its coverage of the Turkish army and the Kurdish Worker’s Party. Apparently ready for printing, the stones respond to the materials making up the adjacent library, housing books ostensibly safe from any regime, and make permanent the struggle of freedom of expression.

The Agricultural University of Athens, established in 1920, will later this month have fifty-four of their sheep dyed in indigo by Aboubakar Fofana, one for each country in Africa. That this will take place days after many thousands of lambs will be slaughtered for the annual Easter feast, will not have escaped the notice of the organisers of this event. Fofana is also responsible for weaving and dyeing, using the same indigo, the bookmark within the hefty documenta14 Reader, one of the several impressive publications released at the inauguration of the exhibition.

At the Archaeological Museum of Piraeus, a shamefully-underexplored wonder that is moments from the city’s main commercial port, the movements of visitors and the shapes of the museum’s contents are investigated by way of interpretive dance. Each weekend throughout the duration of the exhibition, performers choreographed by Kostis Tsiokas, will execute Collective Exhibition for a Single Body, as curated by Pierre Bal-Blanc, a tranquil passage amongst ancient stone anchors, imposing bronze statues and the fragrances of the outdoor collection of columns. One wonders whether such performances should be a mandatory feature of all museums, with this particular piece at least beautifully elucidating the magnificence of the ancient artefacts.

The wildflower-punctuated Philopappou Hill, often neglected in favour of its slightly better-known neighbour, the Acropolis, houses a rather curious marble tent by Anishinaabe-Canadian artist Rebecca Belmore. Located provocatively in the line of sight of perhaps one of the best views of the Parthenon, which the entrance of the tent faces, and the city surrounding it, the work suggests visitors better acknowledge those less fortunate but nevertheless residing alongside us in the city below, and beyond.

The exhibition has also taken an important stance on sound, placing it at the forefront of the programme. Aside from the various music and sound art events scheduled to take place during the exhibition’s one hundred days in Athens, a significant proportion of the artworks installed in the venues have a relationship to the sonic. Perhaps the most striking of these is Emeka Ogboh’s The Way Earthly Things Are Going, a 12-channel installation within the main unfinished auditorium of the Conservatoire. An affecting choral score sung in Greek, the piece evokes Native American song and invites its audience to questions the state of the world, with an LED global stock ticker illuminating the cavernous concrete hall.

Additionally, a recent refurbishment of one of the world’s most important electronic musical instruments, the Synthi100, designed by London’s Electronic Music Studios in 1971 will lead to its unveiling in the coming weeks and subsequent performances of new pieces composed specifically for the instrument. Its blueprints, as well as archival photographs of a legendary synthesizer concert at the ancient amphitheatre of Herod Atticus are displayed between EMST and the Conservatoire, highlighting the prominence of the festival’s interest in historic influence on the present.

It is hoped by Athenians that the end of the festival in one hundred days’ time won’t mean a void being left, or documenta’s complete departure, but rather the continued development of the relationships forged. One project off Victoria Square by Rick Lowe has installed itself as a year-long initiative to instigate dialogues linking the arts with small business and local immigrant and refugee support groups. Discussions and meetings that take place at 13 Elpidos Street contribute to a weekly publication circulated in the area and should continue long beyond the exhibition’s prescribed dates.

These examples are merely a handful of the almost countless works of art that are to be found embedded within the city. While documenta14 has become, for the time being at least, enmeshed in many of the city’s cultural institutions and other less obvious spaces and places, it is of course very possible that whole swathes of the city’s population could remain oblivious to its presence. What seems to tie these and many other pieces together is their success in reformulating one’s preconceptions of their locations. I think that the ultimate success of the exhibition can only, therefore, be assessed in the long term, as it is slowly revealed to what extent its intended wider-reach has had a transformative discursive effect.

‘documenta14’ runs from 8 April until 16 July in Athens, and from 10 June until 17 September in Kassel. documenta14.de.

Banu Cennetoğlu, Gurbet’s Diary (27.07.1995–08.10.1997), 2016–17, various materials, Gennadius Library, Athens, documenta 14, photo: Freddie F.