Snapshot is a new weekly series that zooms in on a single photograph to explore the context of an image, the conditions it is created within and its wider cultural impact.

New York, 1987. The AIDS crisis looms large in the city, tearing apart its queer community with grief. Property is still cheap, but the financial boom is taking hold of Manhattan real estate, driven by wealthy developers like Donald Trump, who would go on to redefine far more of the world than anyone could have imagined. The lives of gay men and women in the city are under threat in more ways than one, with the safe havens of clubs and subcultural venues increasingly priced out. During these turbulent, fast-changing times, photographer Stanley Stellar is busy documenting the city.

Over his more than forty-year career, Stellar has been a prolific photographer of life on the margins in New York. He looks to the underside of the city in frequently unposed and intimate images of its inhabitants, notably within the queer scene that he himself has long been active within. Born in Brooklyn in 1945, he first pursued a career as an art director and graphic designer, before moving towards photography in 1976. “I’m a New York native, and I felt very comfortable on the street with my camera,” he tells me over the phone. “I didn’t feel like an interloper, I felt like I was part of the street culture. Before the internet revolution, if you wanted to meet anybody on a social or sexual level, you had to leave your house. At midnight, if you didn’t want to go to sleep, you had to decide to go out into the city. You had to be on the street.”

“Much of my work is about my love of the gay culture I was in, and it was still pretty much a world unknown”

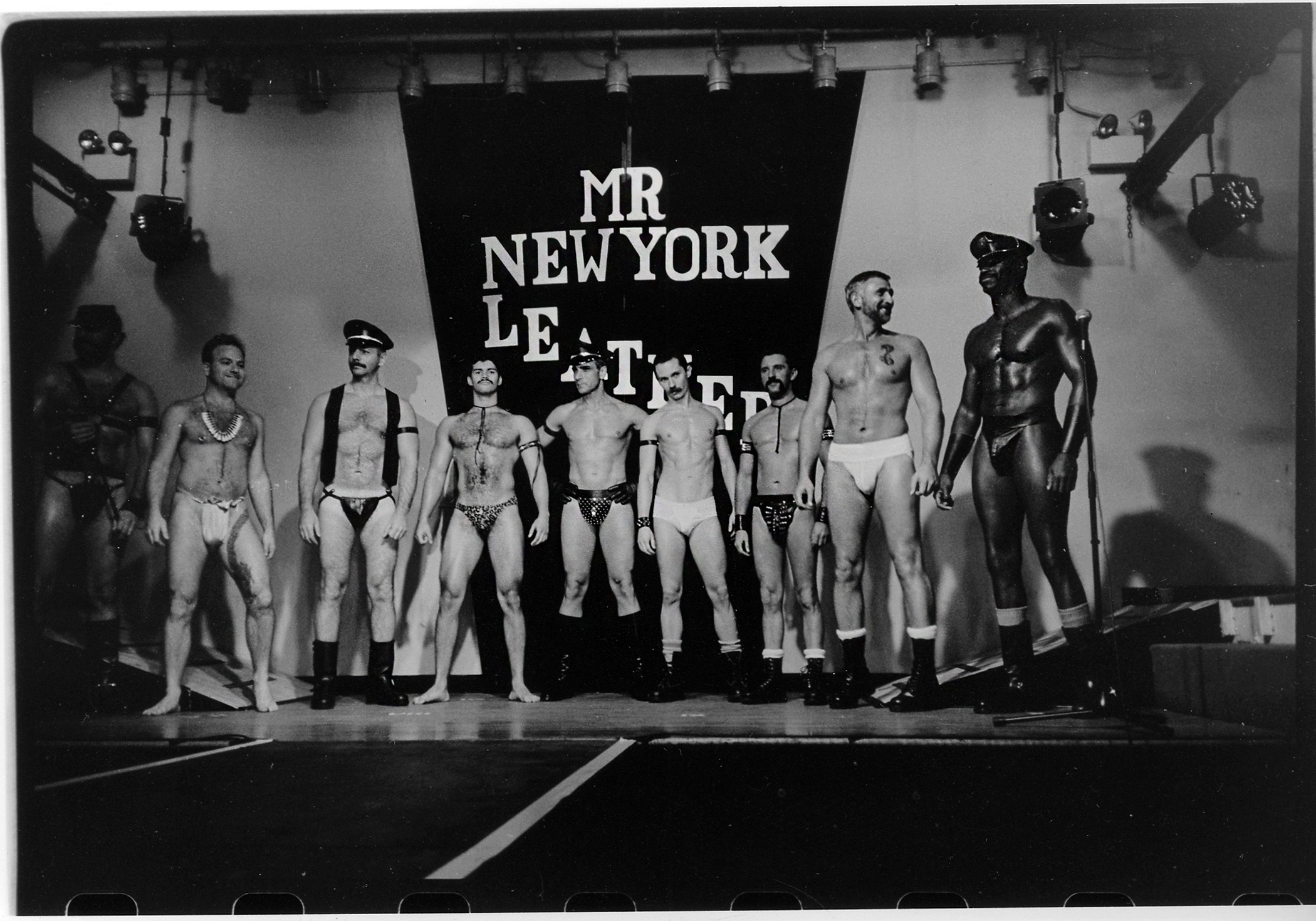

Stellar worked as a staff photographer for a weekly gay newspaper in Manhattan during the 1980s, who sent him to events across the city that he may never otherwise have stumbled upon. One of these assignments took him to the Mr New York Leather contest—part of a subculture that focuses on the erotic qualities of leather garments, such as vests, boots, chaps and harnesses. “When I started at the newspaper I really welcomed that opportunity to crossover from street photography, to go to places and visit events,” Stellar says. “Some of the people who I met for just one hour are still so monumentally dear to me. It was about how I related to them, and how they related to me.”

That ease and familiarity, even between strangers, is captured in a casual snapshot by Stellar from the night. The men are visibly relaxed, their eyes darting in different directions, like a moment snatched with a friend before a big event. That they are onstage, banner emblazoned behind them, suddenly doesn’t seem to matter in this shot of the group at ease before the poses are struck. There is a quiet intimacy to the setup despite the performative costumes and unseen audience, helped by the framing of the image to include the stage lights. A photographer reveals as much through what they choose to omit as they do in what they include, and Stellar offers an unguarded glimpse of an underground scene at play.

“I wasn’t shooting from a place of money or intellect; I don’t even like clever ideas, and I’ve always been doing it from my heart,” he reflects. “Much of my work is about my love of the gay culture I was in, or my appreciation for it, and it was still pretty much a world unknown.” That same year, in 1987, ACT UP was launched by Larry Kramer, at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center in New York, to advocate for the rights of those living with AIDS. To identify openly as queer was stigmatised, and the gay clubs and parties organised were not only celebrations but a means of community and resistance. It was in this context that Stellar navigated the city, often operating in the face of extreme discrimination. As he points out, the newspaper that he worked for never used any contributor’s real name in their masthead, and even the street signage for their office was a generic one.

“I was never looking at everyone from the outside in. I was looking at them while being them, standing with them”

This existence on the margins brought people from all walks of life together within the community, united in their shared experience both of misrepresentation in the media and outright homophobia on the streets. The queer scene in New York remains diverse in its racial representation, and the 1980s saw the emergence of ball culture into the mainstream, memorably captured in the 1990 film Paris is Burning. The documentary depicts the lives of transgender women, gay men and drag queens, primarily from African American and Latinx backgrounds, as they perform at drag “balls” and move freely around the city. Like Stellar’s deeply human portrayal of his subjects and friends, the film went beyond the pain of a decade dominated by AIDS to show the joyful, uplifting moments of release.

Stellar’s group shot at the Mr New York Leather event might be a casual one, but it tells a bigger story of a community who paved the way for a more inclusive culture that so many take for granted today. “I felt very comfortable in my role as a visual artist, because I was never looking at everyone from the outside in. I was looking at them while being them, standing with them,” Stellar concludes. “I just felt honoured to be able to represent my peers, my culture and my time.”