J Wortham interviews five people across multiple generations and backgrounds to reflect on the cultural legacy of Ralph Hopkins’ iconic beach parties and their revival. With introduction from Gili Rappaport.

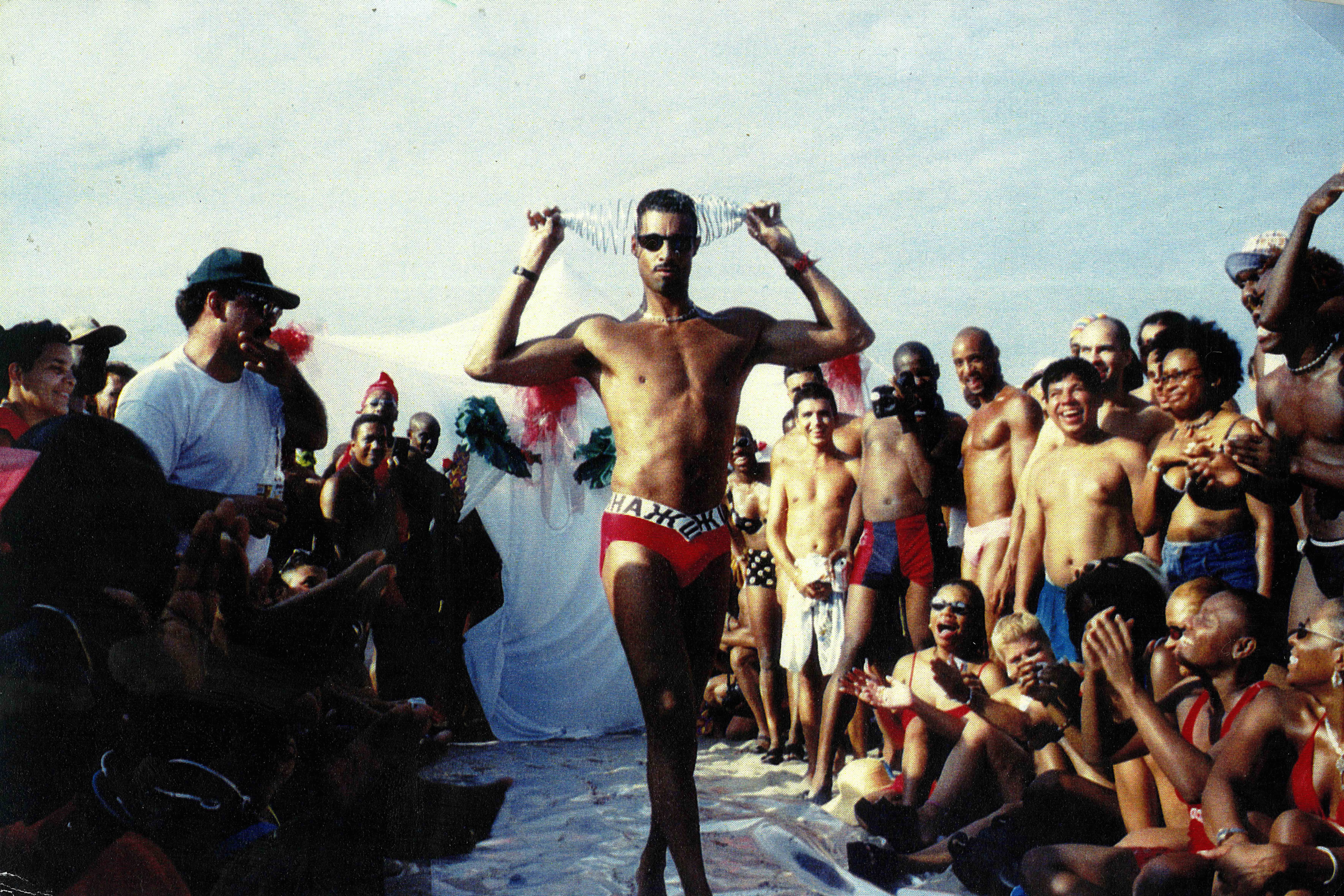

Ralph’s Beach Parties are parties from history to today in which today is also history. Ralph says directly, often: they are to “see things that people have never seen”. Rhythmic movements, rising and falling in graceful colors and undulating fabrics rolling on the shoreline of the sea, shaped by wind from distant storms and luminous horizons. It is the constant ebb and flow of nature. Grounding this party is a particular mylar fabric, a mylar catwalk on the sand. It is a relic. A relic is a piece of a divine body, a tangible link to a bygone era, a revered tradition, preserved for its sentimental value, its symbolic value, its historical value, finally, a remnant of the past.

The parties also involve a kind of belief. Associating ourselves with a certain faith, a certain truth. We feel pride being part of Ralph’s Beach Parties, because we have found a way, a runway, that is deliberate and intentional, and makes it possible for us to trust in ourselves. To trust in our own eyes and hearts, and our abilities to protect ourselves from internalizing the phobias and anxieties that might confuse our party. Celebrating the shoreline as a space where bodies, creativity, and community intertwine, forming a tapestry of resilience and joy: it is a simple approach. That is the quality of Ralph’s Beach Parties.

This interview gathers voices from five people across multiple generations and backgrounds to reflect on the cultural legacy of Ralph Hopkins’ iconic beach parties and their revival. J Wortham facilitated the conversation with Ralph Hopkins, Halo Perez-Gallardo, and me. Together, we revived Ralph’s Beach Parties on the shores of Jacob Riis in 2022 and 2024, marking their return after more than two decades. J lives and works on Munsee Lenape land, often referred to as Brooklyn, New York. Ralph, a 76-year-old native New Yorker and the heart of these gatherings since the ’90s, also resides on Munsee Lenape land. Halo grew up on Matinecock and Rockaway lands, so-called Queens, and currently lives on Mohican land, also known as Hudson, NY. Photographer Christian DeFonte, who documented the spirit of the revivals, is based in the Catskills on Muh-he-con-ne-ok land. As for me, I was born in New York City and raised near White Plains, having lived on Canarsie and Munsee Lenape land in the Rockaways and Brooklyn for over a decade, and I now reside on Chinook, Multnomah, and Clackamas land in so-called Portland, Oregon.

Across all of us, listed here and among readers too, there is fundamental suffering. The familiar grief is public knowledge. We are all, in different and unique ways, grieving. Acknowledging it, through the ages from history to today, we are on wet sand on the shore together. That is the starting point for the party.

-Gili Rappaport

J Wortham: Ralph, how did you first get introduced to Riis Beach? What was it like when you first started going?

Ralph Hopkins: A schoolmate of mine – his name was Leroy Presley – told me about it. That was in the 60s. When I first went there, I was amazed. I saw so many people and such a big gay section. And it felt natural. It felt like fun. Everybody with different bathing suits and the little beach toys they would bring to the beach, the beach balls, they were bringing tables – actual kitchen tables – and all kinds of food. I’ve never seen that before on any other beach. It just felt right. Seeing people half dressed, half naked. Some were naked. It was just eye-popping at the time.

JW: Ralph, you still go to the beach to this day – you’re a regular. Anyone who visits will see you out there in your neon bikini bottoms, holding down the tradition of gay Riis Beach. Why is it important to you to still be out there, after all these years?

RH: It’s almost like a second home in the summertime. It’s a relaxing feeling. It’s fun. If you’re feeling down or lonely, that’s the place to go, to energize yourself, have fun, see things that you never saw before, and meet people that you would normally never meet in the city or on the street. And it’s nice to be acknowledged when I’m there. They come up to me and say ‘hi’ and ‘where have you been’ and ‘I miss you’, things like that. It means a lot to me, and a lot to them too.

JW: Let’s offer some context for the uniqueness of Riis. Have any of you ever been anywhere that feels approximate?

Halo Perez-Gallardo: I would say that there is nowhere in the world like Riis. Riis is unto itself, and its ineffable nature is what provides its magnetism – you want to return to its magic again and again, partially because you can’t quite name it. Riis provides a quality of feeling that is so rare, this kind of natural high – derived from the purity of freedom expressed along this small strip of city beach. The beach itself is neither breathtakingly beautiful nor so abject as to polarize the beachgoer, but its essential quality is radical. The joy that can be felt is tangible – the air is thick with it. I love Riis, may it last forever!

RH: What makes Riis unique is the different types of people who go there – you have the straight, the gay, the bisexual, but they all sit in the same area. Everybody’s comfortable with each other. It’s a part of the beach that you can be yourself and not be ostracized by anyone and just relax.

Approximate… probably Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Ipanema has a large gay section also, but it’s not as daring or bold as you will see at Riis beach. You don’t see anybody nude or half nude at Ipanema.

Gili Rappaport: Riis Beach is sacred—a rich cultural landmark for New York City and beyond. It’s uniquely accessible, and it’s been a haven for 2SLGBTQAI+ communities (Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Asexual, Intersex, and other gender and sexual minority) for over eighty years: it still blows my mind how the MTA can get you out there, to this spot nestled at the southern tip of Queens along the Atlantic where actual dolphins and whales crest on the shore.

As a non-binary, queer, white Ashkenazi Jewish person born and raised in New York, my experience at Riis is different from those who have deep roots there – obviously, I can never know entirely what it means and meant to Ralph and the Riis community to have a place like Riis. Choreographer and dancer Miguel Gutierrez speaks to this sentiment well, emphasizing the beauty of understanding one’s role as a guest in spaces celebrating others’ agency.

Another incredibly special spot that comes to mind is Rooster Rock, a clothing-optional beach along the Columbia River, about 22 miles from Portland (Oregon). While it’s very different from Riis (nothing is quite like Riis) it’s also important—an open, beautiful space known for cruising, queer community, and stunning views of the Gorge.

JW: I’m dying to visit Rooster Rock! One of the most glorious things about Riis is that people go year-round. It’s not just a place for summer enjoyment. If you go out in fall or winter, you’ll see people camped out there, lighting fires for the winter equinox and skinny dipping on New Year’s Day. It’s something of a miraculous anomaly in that way.

RH: I do have friends that go there in the winter time – they like to go out there for a day or two, even in the cold, because it still has that aroma of the gay scene there that brings you back, no matter hot or cold.

They sit there in the winter with their friends, they make a little fire, and the spirit of the gay crowd is still around you – even though you can’t see them, you feel them.

When they do go back in the winter time, they don’t go to the other side of the beach. They go back to the gay section to relax, even though there’s no police there to bother them or anything like that. The ambiance of that whole area is there while you’re sitting there.

JW: Can you all talk a little bit about the significance of a gay and queer beach in New York in 2024, as we head into another devastating Trump presidency, during a time when our rights are being decimated at an alarming rate?

RH: It’s almost like having a Gay Center, which they have on 13th Street in The West Village, on the beach. And if anybody straight comes along and wanders into the gay section on the beach and attempts to bother somebody gay, other gays will come around to help, to protect you.

HPG: Queer spaces are so rare these days. Sure, whatever, “lesbian bars are back!!!” But the beach is FREE! It’s public! There are almost zero public, outdoor spaces I can think of where queerness can be celebrated so safely, so freely, so entirely. The rights of marginalized people everywhere are under attack, our voices are consistently silenced, our rights stripped. Riis is a haven because it’s a place where we can still imagine freedom, still taste it, and still believe that, one day, we will be free.

JW: Halo, you’re reminding me of the role of some of the contemporary stewards of Riis who recently raised money for a beach mat to help make Riis more accessible for our disabled community members and folks who use wheelchairs. It’s a place where we can build the futures we want to see in our lifetimes.

GR: It’s true! The ongoing erosion of 2SLGBTQAI+ rights is deeply concerning, highlighted by the rise of anti-trans legislation and funding bans limiting access to healthcare. These include threats to Medicaid, Medicare, and ACA Plans (Affordable Care Act), removing tax benefits for providers offering care to trans people, and outlawing gender-affirming care for trans youth and potentially adults. The PDMP (Prescription Drug Monitoring Program), which tracks medication usage, is already impacting women and many people in some states seeking reproductive health. Additional threats include restrictions on participation in sports and education (defunding schools allowing trans-inclusive bathrooms), rising hate crimes, and legal battles undermining employment and housing protections. Amid these challenges, Riis stands as a sanctuary where community members can embrace a whole self and celebrate diverse styles, colors, and energies. Supporting community organizations like GLITS is crucial to providing trans people with the resources to live, heal, dream, and build collective power.

Ralph’s party took place beside the fenced-off section of the beach, closed this year due to severe erosion and expected to remain so through 2025, per the National Park Service. This serves as a poignant metaphor for our diminishing rights. Riis actively embraces diverse identities, celebrating bodies of all kinds. It is a site of resistance and resilience, where presence and celebration are radical acts. Riis Beach remains vital for fostering solidarity.

JW: Gili, how did you come to know about Ralph and his beach parties?

GR: In the fall of 2020, I moved to the Rockaways, seeking solace by the ocean during my mother’s battle with cancer and to connect with my maternal grandmother’s spirit. Living near Riis Beach, I encountered Ralph, The Mayor at Riis, whose warmth and stories about his iconic 90s beach party fashion shows captivated me. Over our first lunch, he welcomed me almost maternally. Listening to Alexis Pauline Gumbs discuss her new book Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines (PM Press, 2024) with Adrienne Marie Brown on ‘How To Survive the End of the World’, I thought of Ralph. He shared his dream of making a book about his beach parties, and eventually, I utilized my graphic design and archival experience to collaborate with him on it. With Halo’s vision and generous sponsorship, we revived the shows as Ralph’s Neon Oasis Beach Party in 2022, recreating the original decor like the mylar runway and the color-themed outfits and matching flags, and involving past and new community members. A poignant moment was Ralph selecting neon orange nylon for the 2022 party flags—the same fabric I’d used to decorate my mother’s hospital room—symbolizing connection and legacy. After three years of collaboration, we recently released They Call Me The Mayor At Riis Beach: Ralph’s Beach Parties 1994-2000 (Anthology Editions) at Ralph’s Red Hot at Riis in 2024.

JW: Gili, can you talk about your practice as an artist, and the desire to facilitate movement-based revivals that help people get back into their bodies and spirits through connecting with nature. Can you talk about how this work serves as an opportunity for community reclamation and queer expression.

GR: I am influenced by artists like Ana Mendieta, who said “My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that unite me with the universe. It is a return to the maternal source.” I work across disciplines to consider ecologies of separation and explore how we can reconnect with each other and the land. It is rooted in moments where we, myself included, can reinhabit our bodies and find grounding in community and nature, countering a culture that often encourages dissociation from all of the above. As a naturalist, I look to the Earth as our grounding force, carrying the resilience of past generations and opening new pathways for collective solidarity and connection.

Movement-based revivals allow us to physically and spiritually engage with these spaces across time. This work feels especially powerful within queer communities, where reclaiming public spaces for expression and solidarity challenges norms and invites experiences of freedom and belonging that our society doesn’t always nurture. I keep asking: how can we reclaim space, not only for ourselves, but for shared connections with the Earth and each other?

JW: Halo, how did you come to know Gili and Ralph?

HPG: I met Gili through my cousin Cristina (Aguayo) and their friend Seth Caplan from high school. Gili, Seth and Cristina met in college and years later we were all introduced. In 2022, Gili and Seth interviewed me for Office Magazine and it was around then that Gili mentioned their friend Ralph, and I was immediately fascinated with his story and persona. I had to meet him! I guess at some point I casually suggested to Gili the idea of reviving Ralph’s parties. It felt like a natural alignment for Deb’s (we had thrown parties at Riis in collaboration with SPECTRO – previously known as Two Dudes), the burger spot owned by my friend Tyler (Wright). Gili and Ralph were down, and so the planning process, and a deepening friendship, began to unfurl.

JW: Halo, I’ve often thought of Lil Deb’s Oasis, as a kind of proxy for Riis Beach upstate. Does that resonate for you? Was that among your intentions when starting the restaurant?

HPG: Wow that hella resonates! Thank you, ha, sincerely. At the core of the vision for Deb’s was the “Oasis” of it all, and – that’s exactly what Riis provides. Though Deb’s wasn’t conceived as a queer mecca, it became one, as Riis was simply born a beach, but became a beacon of hope for queer people to revel in their own delightfulness. Someone recently commented that the restaurant reminded them of John Waters, from the food to the interior space, which is maybe the second best compliment we’ve ever received (second to yours!). Both comments make me feel really seen in who we are and what we’re trying to do.

JW: I know you all have been thinking a lot about nature as a healing space for queer and trans communities. Can you each share about when/how that started for you?

RH: Going out to the Rockaways is a place where you could feel peace, relax, and rejuvenate yourself. Take away the worries of city life for a couple of hours.

GR: It began with recognizing the deep connection between environmental justice and social justice. People for Mutual Education have a pamphlet on this topic available for free.

My thinking on this topic is also influenced by Mel Chin’s work, as discussed in Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Duke University Press, 2012). Chin’s exploration of biopolitics underscores how environments, identity, and healing intersect, highlighting the importance of creating safer, more regenerative spaces for marginalized communities.

It also began with personal experiences that helped me see and affirm myself in nature’s cycles of transformation. One such moment unfolded when I encountered a monarch butterfly along the shore of Rockaway Beach after a snow, long before I met Ralph. I placed the butterfly on my altar, and later dreamt my body was transforming into a butterfly—changing, growing, and taking a new form. When I woke, its wings were broken. That moment symbolized, for me, the delicate and interconnected process of transformation and resilience, something that resonates deeply with queer and trans experiences. Nature, in its autonomous and wild cycles of change, offers a space where we can see our own experiences reflected – making it a supportive, healing teacher, not just for myself but for queer and trans communities as a whole.

HPG: This is something I’ve thought about a lot with Deb’s as well. I think that historically, queer people have gathered primarily in cities because of their density and the feeling of safety that comes from that. When it became clear that Deb’s was becoming a safe haven for queer people, I thought a lot about the impact of providing access to the pastoral through our space. By opening a restaurant that openly celebrates and accepts queer and BIPOC folks both through our service style and in our employment practices, we effectively created a portal for folks to build community in Upstate New York. Of course, the downside of this type of great migration can have a downsides as well: is its impact on local communities – raised rents, and the displacement of locals through gentrification, something we’ve worked hard to mitigate through our mutual aid work. By no means is this work a solution for the root of the problem, but it’s a way to build awareness, give back, and hold space for interconnectedness of our shared realities.

JW: What made you all want to bring the parties back? And can you share a bit about their role in community building, queer culture, and artistic expression in the midst of the evolving landscape at Riis with the city demolition, beach erosion, gentrification, and political change?

RH: It took Gili and Halo to help me get back into my beach parties. Years ago when I had to stop throwing the parties, it wasn’t my choice. Another group had a couple of fights at their parties on the beach, and they didn’t clean up the trash after their parties. The Parks (National Parks Service) had offered them a bill to clean up, and they wouldn’t pay that bill. So the Parks said “Okay, well, no more parties for anybody.” So that’s what got me to stop my parties – they were not giving permits at that time. Back then, the crowds around my parties were at least 1000 people on the beach.

GR: After the election, journalist Erin Reed spoke of these times as a generational struggle. She described how the decisions we make now plant seeds that grow trees for everyone to enjoy in the future. Bringing the parties back was also asking: how can we embrace the past to understand the present? What can being in the realm of present experience with this work teach us that an interpretation of it cannot? How can we pass love through generations to carry, and how does that help our resilience in the face of grief?

There’s also just a pleasure component — the moment Ralph first walked out onto the runway at the 2022 Neon Party was truly one of the best of my life, I just cried in awe, the crowd of hundreds on the beach stood up cheering and applauding. I began to trust what we were doing, and my enthusiasm grew as energy continued to grow.

JW: What inspired the Red Hot party in September?

RH: I go by the colors. The color red against the white sand is very pretty to me, and it’s a hot, fiery, rich color that you can see from far away. So when we made the eight foot poles with the red fabric, they stood out from a distance.

GR: Everyone came dressed in red and the decor was red. It looked GORGEOUS.

JW: Who were some of the models this year? And designers?

RH: I was wearing the designer Lonie Cisco in the beginning of the show, who is a designer that’s been showing at the beach parties since the ‘90s.

I have known the designer Lord Proverbs for at least four years. We met at Fort Greene Park, here in Brooklyn, at dance parties called Soul Summit. He needed models to wear the outfits at the beach, so I said, “I’ll ask my friends from the audience to model”, and that’s what happened.

The models all had a good time. Their names are Shéár Avory, Julio Vega, Yvonne Littlejohn, Keith Lorenzo McCullough, Press Kenady, Tracey Collins, Rico Rican, and Phoenix Amadi. The two performers that Lil’ Deb’s curated, Star & Stan (Reed Rushes and Kate Williams), were very interesting. They were odd and different, and that’s what I like – things that people have never seen before.

GR: The red coat Ralph wore for his entrance at the 2024 party is the same piece by Lonie Cisco featured on the cover of the book They Call Me The Mayor At Riis Beach: Ralph’s Beach Parties 1994–2000. His hat was a nod to another 1997 red party look.

Midnite Abioto showcased her line, Ecological Designs, alongside poetry I read during her runway walk. She traveled from Portland, Oregon, accompanied by her daughters Intisar Abioto and Kalimah Abioto. Model Keith Lorenzo McCullough and designer and model Kate Williams also contributed their garments.Notable designers and models from Ralph’s Neon Oasis Beach Party (2022) included Lonie Cisco, Everett Clark, and curated collections such as Care Instructions, Baggiana, and Boiled Wool. Performers Davon Rainey, PVSSYHEAVEN, and Venus Babes brought energy to the event, with David Storey as DJ. These collaborations celebrate the enduring spirit and creativity of Riis Beach.

JW: Can you tell me about some of the other collaborators for the 2024 Red Party?

RH: The DJ, Lil’ Ray, is very popular in the DJ scene and the club scene. He’s known throughout New York and other cities. He gives parties at Prospect Park called The Jamboree. I just saw him this past Saturday at his birthday party, and the first thing he said to me was, “Ralph, please, please, give another of those parties, your beach party! Please let me know!” He definitely wants to do it again. There was also another DJ named Greg Cee.

GR: The announcer for both the 2024 and 2022 parties – Giovanni Amato – was a model in Ralph’s 90s parties.

Jah Elyse Sayers represented the people’s riisearch group. They brought their oral history booth to the beach and raised money for GLITS. They also began a series of conversations about beach erosion at Riis, with Ahmed Allawalla.

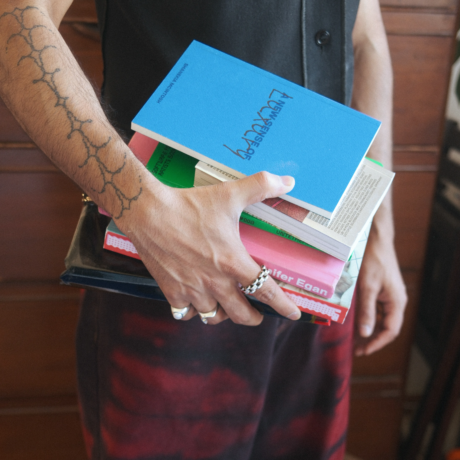

Anthology Editions had a table with stacks of the book They Call Me The Mayor At Riis Beach: Ralph’s Beach Parties 1994–2000, which Ralph signed after the show.

Several of the community members who were at Ralph’s Beach Parties in the ‘90s attended the 2022 and 2024 parties, along with many community members who have continued to celebrate the enduring spirit of Riis Beach.

JW: How did the community respond to this newest iteration of the party – in 2022 Ralph’s Neon Oasis beach party, and in 2024 Ralph’s Red Hot at Riis beach party?

RH: Already three or four different people said, “Well, I’m coming to your party next year. I can’t believe I missed it!” I said, “Let’s see how things go”. I’m saying to myself, “Do these people realize how old I am?”

GR: I don’t think anyone realizes how old you are. It’s a little known secret! (Laughing)

RH: How long do they think I can keep going? (Laughing)

GR: I also think it is important to honor the differences between the newer iterations and the 90s ones. The parties then ARE different from the parties now. Each has its unique qualities that we celebrate together.

JW: From your perspective, do events like these encourage relationships – and perhaps, even a sense of stewardship, of the land? And how do we reconcile the complicated nature of stewardship, which is so fraught in unceded indigenous land – and yet important for the future of our ecological realities and compounding climate crises?

GR: That’s a vital question. I believe events like the beach party can indeed foster connections with the land and inspire a sense of care. The parties engage our senses with the elements of the ocean landscape, and deepen our experiences there individually and collectively. As we make the party together with the beach, we understand ourselves as part of the ecosystem. However, stewardship on unceded Indigenous land is complex and must be approached with care. It’s essential to acknowledge Indigenous peoples as the original stewards of the land and to prioritize their wisdom and cultural practices in any stewardship efforts.

Ralph, do you think that having the party on the same site every year encourages us to have a deeper relationship with that particular place, with that land?

RH: That part of the beach always has that. That’s why it draws us back to that same area, year after year. For the beach.

GR: Do you believe that the land holds the stories of the parties?

RH: Oh yeah. The beach has seen a lot. It’s too bad it can’t talk back to us!

JW: Maybe the land does!

GR: Absolutely, it certainly does.

HPG: One of the most gratifying gifts of the beach parties has been their intergenerational nature. It’s increasingly rare for younger generations in New York to connect with queer elders as queer spaces dwindle. Ralph’s parties are special for bringing generations together, fostering deep emotional connections and a sense of community. For example, I dressed and photographed Martine, a fab Riis Regular in her seventies, in a red outfit she loved, capturing her joy in the water. These moments, more meaningful than casual bar encounters, strengthen our ties to each other and the land.

Land holds memory. By building community on land with care and connection, we create ties that deepen our interconnection through our bodies. While this doesn’t undo the violence endured by Indigenous people, such gatherings can hold karmic power, helping us understand the land’s histories and inviting others to arrive with care.

JW: The glory of Riis Beach feels fleeting and fragile, which is part of the ever-evolving dynamic of queer safe havens. They often disappear as quickly as they appear. Do you find that tragic or is despair too luxurious to even consider?

RH: The beaches, the erosion is making it shorter from the boardwalk to the water, and that’s scary. Also, it’s a younger crowd, but it’s a younger crowd because they are just discovering Riis beach and it’s their time.

GR: It’s such a beautiful question. While we mourn the losses, despair can feel like a luxury in the sense of what we are afforded within our limited capacities. Yet I know grief to be important to endure – the only way out is through. Each safe haven may be temporary, but the spirit that builds them is enduring, and that resilience is what drives us forward.

At the same time, as I see the beach eroding, I feel more in tune with the realities of our climate emergency and how it intersects with racial, economic, and other forms of structural injustice, and more motivated around my personal impact. I try to remember that small gestures can have big ripples.

JW: Like, for example, the book and parties?

RH: Yes. Now through the book, people that had not come to my beach party years ago can get an idea and see photographs of how Riis beach used to be fun back then – the actual parties, the runway, the models. As far as I know, there has never been a fashion show on Riis beach (that I know of). I’ve never heard of one before. So that makes me feel very special for that.

It took us three years. To find a publisher. People said they were interested, then not interested. So much up and down. But, it finally came through.

GR: We found Anthology, an independent publisher in Brooklyn known for elevating archival practices with works by artists like Jerry Hsu, Jonas Mekas, and Norma Tanega. Their reissue of lesbian photographer JEB’s Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians (self-published in 1979, reissued in 2021) was particularly meaningful to me, serving as a reference point when Ralph and I started working on the book. We released the book at the recent red party with a limited run of 1,000 copies that Anthology printed and is distributing at bookstores nationwide.

JW: What are your thoughts on the future of Riis Beach? Due to gentrification and development of the Rockaways and the surrounding areas, it’s not clear what will happen to our safe haven. What are your thoughts on the ephemerality of queer spaces?

RH: I hope Riis beach gets fixed up to make it look like it used to be back in the 60s and beyond. It used to have a lot of restaurants in the bathhouse building! It was really nice years ago. Just five, six years ago, they had some restaurants on the bottom of the bathhouse building, again – seafood, ice cream. They even had a bar selling liquor. It was really nice, selling chairs and umbrellas.

I don’t think they will ever get rid of the gay people at Riis. That area has been gay for as long as I know. The gays are still going to come out there. There’s no other beach in New York that has a section like this.It’s getting bigger, not smaller in my mind.

GR: Is there anything else that you wanted to say, Ralph?

RH: I want to thank everyone for coming to my parties and always being so nice to me at Riis beach, and in the streets also.

The universe realized what I was doing – I just needed some help to bring it out more to the public. I couldn’t afford to do it now the way I used to back then. I’m retired now. I have dental bills and hospital bills. I’m on fixed income. In the ‘90s, I was working so I had more money coming in. I was doing it all myself – the generators, poles, fabric. So I needed help, and God sent me Gili and Halo! I’m very grateful.

J Wortham is a sound healer, reiki practitioner, herbalist, and community care worker oriented towards healing justice and liberation. J is also a staff writer for The New York Times Magazine, and co-host of the podcast “Still Processing.” J is the proud editor of the visual anthology Black Futures a 2020 Editor’s choice by The New York Times Book Review, along with Kimberly Drew, from One World. J is also currently working on a book about the body and dissociation for Penguin Press. J mostly lives and works on stolen Munsee Lenape land, now known as Brooklyn, New York, and is committed to decolonization as a way of life.

Ralph Hopkins is a 76 year old native New Yorker residing in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn. Known as The Mayor at Riis Beach, he threw participatory beach parties there in the ‘90s involving fashion shows, DJs, and food, and has been a consistent presence for the past six decades. He is also a former chef, and in the ‘70s, became a five-time gold medalist—and one bronze—at the Madison Square Garden Harvest Moon Ball for the Lindy Hop and Jitterbug. He is also a US army veteran.

Gili Rappaport is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, and naturalist raised between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. Gili authored the anthology book of interviews I See What You See (KSMoCA), and co-authored the three-volume set Field Guide To the Northeast, with Laura Chávez Silverman (The Outside Institute). Gili’s first solo show opens December 2025 at Multnomah Arts Center, with Urban Forestry of Portland Parks & Rec. Their bronze sculptures are in the upcoming traveling group exhibition Subject: at Umpqua Valley Arts, Chehalem Cultural Center, Pendleton Center for the Arts, and Newport Visual Arts Center. Gili is lead instructor for the March 2025 Hollibaugh Seminar, co-sponsored by CLAGS: The Center of LGBTQ Studies at CUNY and the Barnard Center for Research on Women. KSMoCA, and PSU Special Collections and University Archives hold their work in public collections. www.gilian.space

Halo Perez-Gallardo is head chef and creative director of Lil Deb’s Oasis (Hudson, NY). After studying Studio Arts at Bard College, Halo began exploring the relationship between cooking and installation/performance through kitchen work. In 2016, they co-founded Lil Deb’s and have since cultivated the project into a thriving restaurant, site-specific installation, and performance venue for queer collectivity and maximalist sensation. Office Magazine, The New York Times, Vogue, and Dazed Magazine have profiled their work. Their cookbook, Please Wait to be Tasted (2022), and restaurant are James Beard nominated projects. Halo’s work and life is driven by pleasure and generosity.

Christian DeFonte is a photographer based in the Catskills of New York.