We meet at Doug Aitken’s studio in Venice, California, a family home that has the trappings of that slow, laidback, always-sunny, gate-and-garden kind of modern California life, but the manic energy of a studio where multiple projects are coming together at once. I would call him a multimedia artist, but I’d rather have Aitken do the name-calling around here. Whatever he is, “multi-” seems an inevitable prefix for an artist whose works include installations, interventions, films, photographs, sculptures, interactions and enormous ideas and questions. Winner of the International Prize at the Venice Biennale in 1999, among many other accolades, Aitken is synonymous with projects that decisively step out of the art world and into the greater one beyond, among them his 2007 work Sleepwalkers, composed of interrelated short films featuring Donald Sutherland, Tilda Swinton and Cat Power, which turned eight exterior walls of the Museum of Modern Art into projections over 53rd and 54th Streets in Manhattan.

Aitken is in the middle of a film edit when I ring the doorbell. Among many other things, he is preparing for a show at his LA gallery, Regen Projects. As he will explain later, he’s also working on a big finale to his trilogy, ten years in the making. Meanwhile, he continues to work on a series of original films as part of his epic Station to Station project, which “took off” in September 2013 as a train (“a moving, kinetic light sculpture”), whose freight was art, music, architecture, culture and conversations. Over the course of a month, the train moved from New York to San Francisco with stops in Pittsburgh, Chicago, Minneapolis, Santa Fe and five other American cities along the way, marked by events or “happenings” at each destination.

Within the project itself, but also looking back at its origins, Aitken keeps asking the same question: “What is creativity in the twenty-first century?” The question drives the Station to Station original films (available on the website stationtostation.com), which interact with artists like Olafur Eliasson and Urs Fischer, musicians like Thurston Moore, and concepts like the “road trip” as voiced by writer and filmmaker Rick Prelinger.

Aitken is interested in having the ground fall from beneath the viewer, in taking away the stability of place, the support of walls or even the parameters of who exactly does the talking and when. In the few hours we spend together at his studio, he keeps turning the questions on me, asking about my projects, what brought me to his studio, whom else I’ve met, as if proving a point about the various sinews that connect art to world to literature to architecture. In an age of humble brags, how can I resist talking about myself to Doug Aitken? But somehow I do manage to turn the interrogation back on him, and so we come back to this question of art in the twenty-first century, and particularly Aitken’s role within it.

Do you have a shorthand way to describe the way you work as an artist?

No, I’ve never been able to define myself by a medium, as working in one way or one aesthetic, although I really do have a great deal of respect for “the idea”, in and of itself. The question I think about is: if there’s an idea or an impulse, how do you allow it to grow and become its own language?

Does that mean your work is conceptual?

Some of it touches on the birth of conceptual art, which was very much about the purity of concept: early conceptual art is not about the aesthetic, style or medium, it’s just about the idea. And if it’s strong and provocative enough, or asks a haunting question, then that idea will find a way out. In that case, the artist has to think like an architect and create a structure for that idea to get out there in its purest form. Right now is a fascinating time to be making art—or anything. In terms of communication and how ideas are distributed, we’re in a revolutionary moment. We’re moving away from a linear way of working.

Does that more accurately reflect the way ideas are formed, naturally?

Yes, I think the human imagination, the human curiosity, is very fragmented. We have the ability to explore and experience and think about many different layers of ideas and understandings at once. We don’t think in a straight line. Personally, I’m not interested in working in a straight line, either. I’m not that interested in finishing one project before moving on to another. I like the idea of making things that grow in different directions at once. I like to allow different projects to grow as a system. Sometimes they feed off of each other, other times they push off of each other. It’s a continual process of breaking and remaking. There’s a moment with most projects, in which an artwork actually starts putting up resistance, as if it wants to create itself. As an artist, your job is to shepherd the work into existence. Artwork never just comes out of an artist’s solitude or social interaction, it comes out of its necessity to exist.

Within your own works, what exactly has a “necessity to exist”?

For example, Station to Station needed to exist in order to create a new space for experimentation in culture. Culture has become segregated: you’ve got film over here, contemporary art over there, music elsewhere. Much of the segregation comes from capitalism, and the fact that a capitalist structure creates a marketplace, a series of jobs or a kind of micro-industry. You see the strange rubble that’s become of the music industry because of it; and you see contemporary art, with its galleries and art fairs, which is another form of very aggressive capitalism.

“What is our language today? What is it, beyond the creative languages of the past?”

But despite this segregation, I feel that if you sit down with people from ‘different’ aspects of culture—whether architecture, literature or art—and you have a conversation, you find that you’re actually all part of one dialogue, even as the systems that exist are absolutely separated. So I felt there needed to be a space for new experimentation. It was an attempt to answer the question: what is our language today? What is it, beyond the creative languages of the past? Station to Station is based on the principle that if you create a nomadic platform where systems are moving and changing all the time, and you no longer feel the weight of the system that you’re working in, the result could be a freer place for exchange. At that point, the ground falls and your eyes open. Maybe you become more aware of everything around you, the details of it, the details of your surroundings.

It seems to me that “displacement” is often addressed in your works.

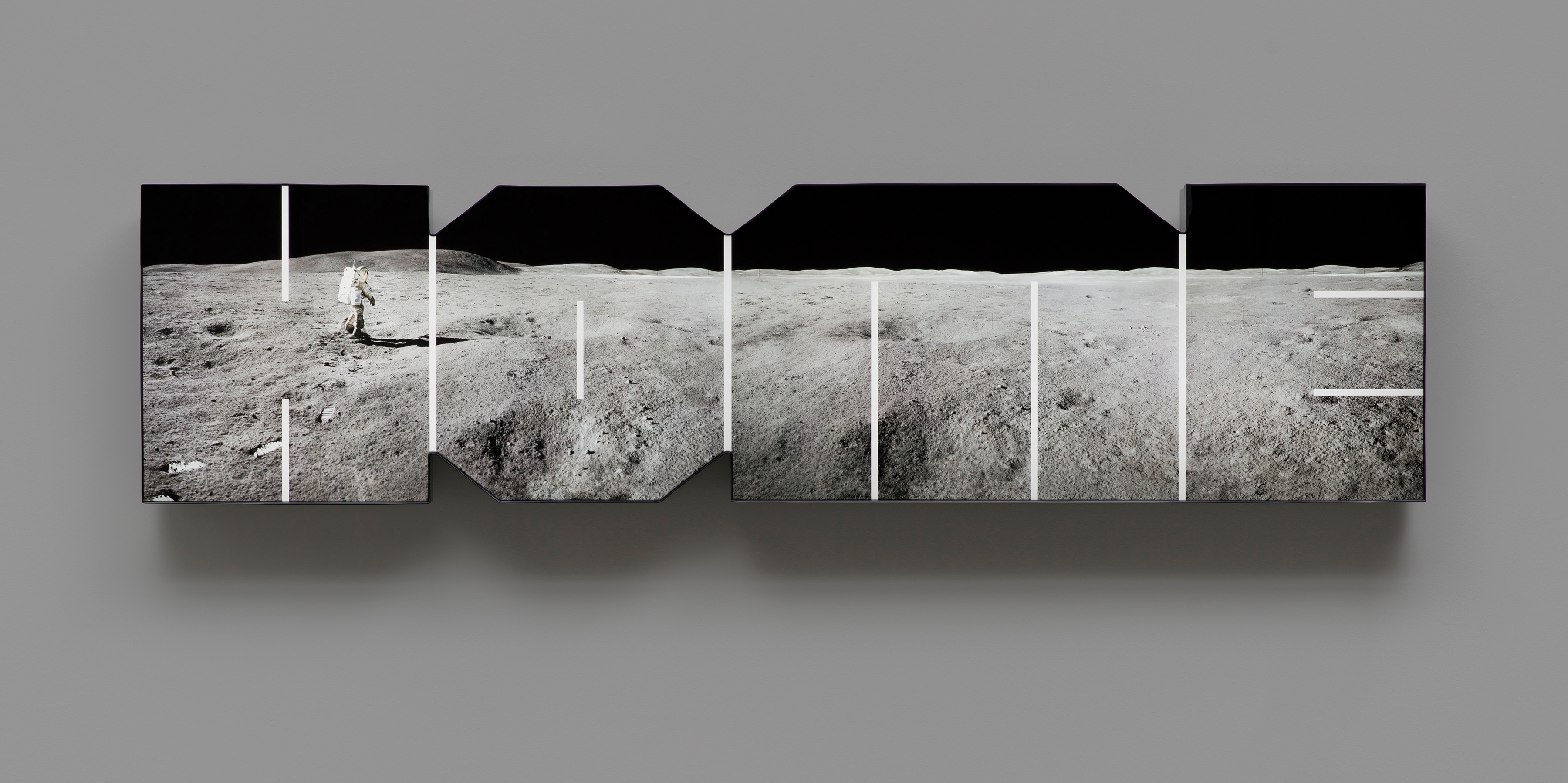

When you’re displaced, there’s a sense of newness, an invigorated quality around you. I’m working on another project right now that gets at this. It’s part of the trilogy I’ve been working on for the last ten years, which includes three separate works—Migration (2008), Frontier (2009) and Black Mirror (2011)—that I’ve made in different places at different times. This project will be the first moment that they come together to create the trilogy that they’re intended to be. It was originally supposed to open at a major museum [Aitken can’t reveal which one], but they tore the museum down for construction. There’s no museum. And in a funny way, that’s exactly what I wanted. The museum is all over the city now, and one idea is to have the project all over the city, too. This allows the viewer to discover the installation—come across it—as opposed to go to see it in an institution. It’s been very interesting to think about positioning these pieces, which are very hallucinatory and holographic. They take viewers through worlds of sound and moving image.

“When you’re displaced, there’s a sense of newness, an invigorated quality around you”

So where in the city would they ideally be?

On a waterfront, on a series of abandoned docks, in an area that people don’t really go to. We’ve been looking for the right place for close to two years, and there’s just something about the waterfront and rusted warehouses. There’s no outside access, no graffiti, the buildings are barely intact, rusted and cavernous. It’s a very mysterious part of the city. It makes me think about how it can actually survive, so completely outside of the existing system.

With this project and others, such as Station to Station, is it important to you that the people seeing your artworks aren’t necessarily those who would have come to a gallery opening?

I love going to a great museum and seeing an amazing body of work. But we’re not contained. At least, as people, we shouldn’t be contained. Why are we making things to exist inside buildings only? Where does the role of walls and buildings actually play into what we create?

You think people look forward to transformation? Change is scary.

But energy is created through change. Contemporary art is so much slower than the development of other parts of our culture right now, and that’s unacceptable. I think that anyone making things has a responsibility to experiment and question things as much as we can—or at least as much as we want to. Because if there’s stasis—if things always remain the same, and the same, and the same, and the same—then they have less possibility to grow. Risks are necessary for survival.

All images taken from the show Still Life © Doug Aitken, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles

This feature originally appeared in issue 21

BUY NOW