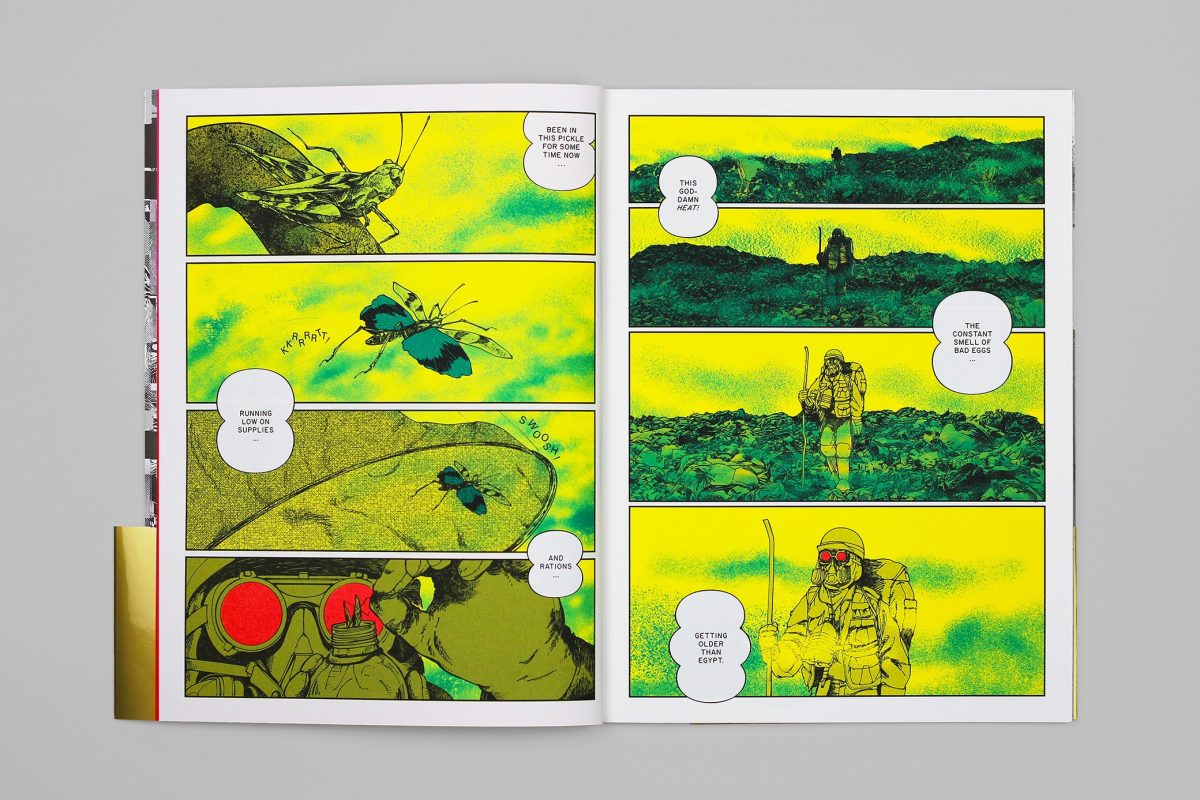

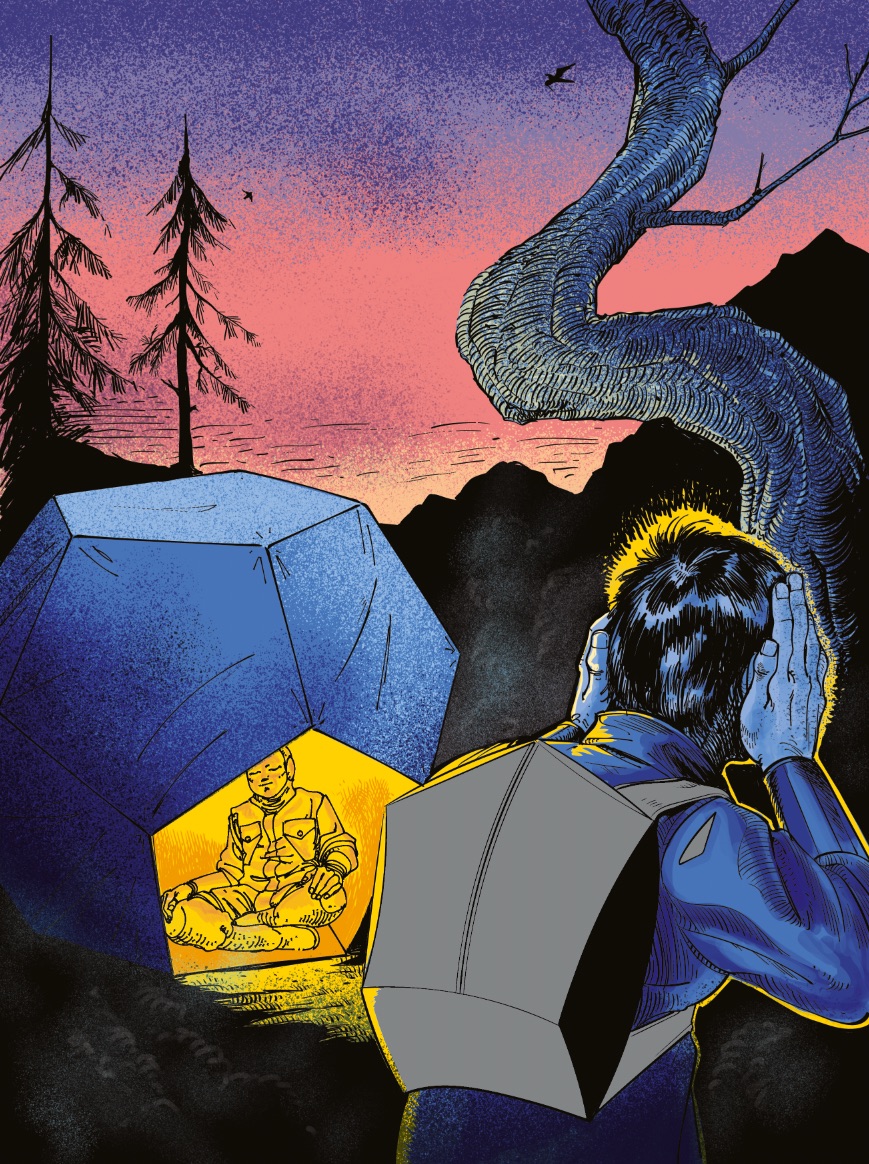

Three figures in bright yellow beekeeping suits hover above a stricken, post-apocalyptic landscape in which only wheat can survive. In another image, a masked anonymous individual gazes into an illuminated chest of jelly cubes amidst a hazardous environment. These fantastical scenes were conjured for Elephant by Dutch designer, illustrator and experimental comics artist Viktor Hachmang, whose work often blurs the boundary between art and science fiction. Originally trained as a graphic designer, Hachmang came to illustration gradually, attracted by the immediate visual expressiveness of the medium. “Drawing is now really central to everything I do,” he says.

For Elephant’s latest print issue, Hachmang was invited to create illustrations in response to speculative designs by five artists for surviving their own imaginary apocalypse. The concepts by Lawrence Lek, Sharona Franklin, Rafal Zajko, Zadie Xa and Estrid Lutz, whose practices centre on rite and ritual, as well as new forms of technology and ecology, ranged from the impossible to the terrifyingly real. “The overlap of the arts and the futuristic idea of apocalypse was a perfect combination for me,” Hachmang reflects over the phone from Amsterdam.

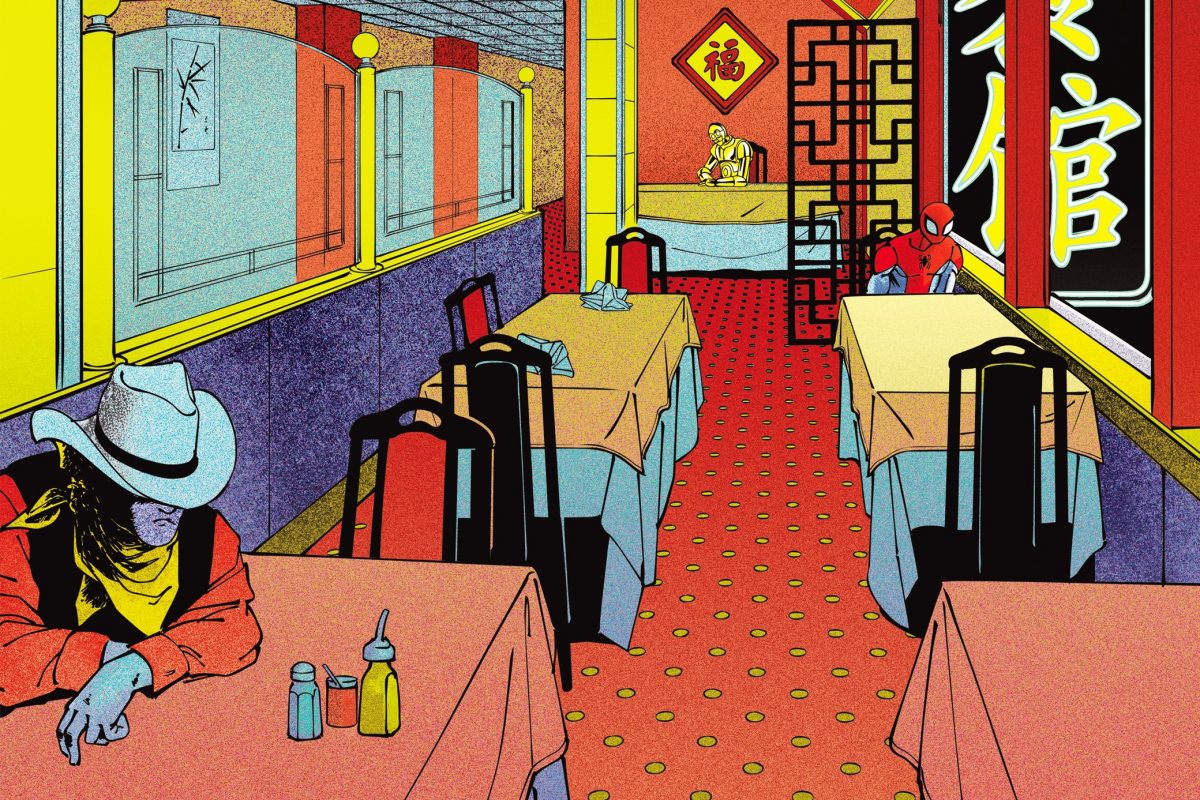

- Illustration for Jacobin magazine, 2019 (left). Illustration for Bloomberg Businessweek, 2018 (right). Courtesy Viktor Hachmang

Hachmang developed an early interest in science fiction from his father, who is himself an artist and sculptor. Together they would often consider how art could function as a solution to future problems, prompting conversations on utopia and dystopias that would go on to have a lasting influence on Hachmang’s own artistic practice. It gave Hachmang the ideal basis for exploring the issues raised in this expansive, ambitious commission for Elephant. “The ideas that the artists came up with were similar to some of the things that my dad and I would discuss,” he says.

“The overlap of the arts and the futuristic idea of apocalypse was a perfect combination for me”

For the visual direction of the images, Hachmang drew on pulp science fiction book covers from the 1960s and 70s. Futurist designer and illustrator Syd Mead was another important influence. As the art director and props designer on films such as Blade Runner, Star Trek and Tron, Mead was accustomed to designing for fictional scenarios, but he also made a career as an industrial designer for the likes of Sony and Minolta during the 1970s and 80s, building “very commonplace subjects that he made into his own”, as Hachmang explains.

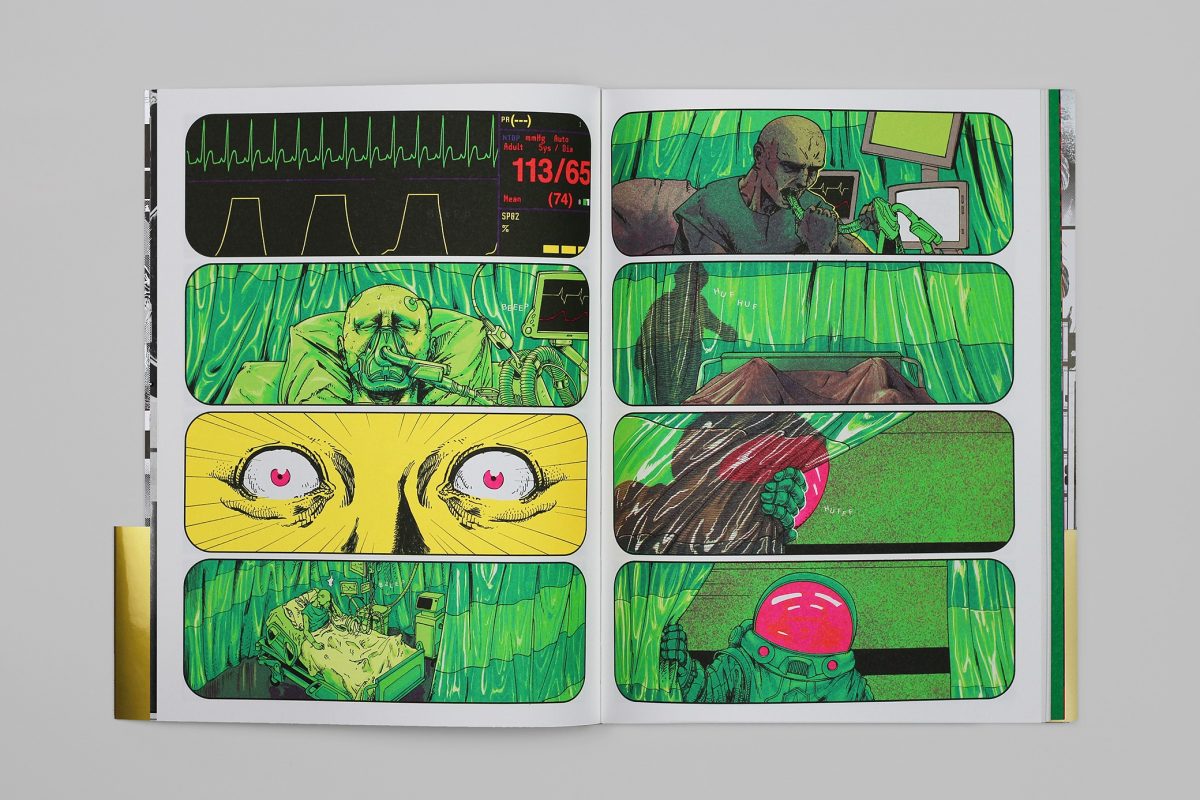

- Bestiarium, 2021. Courtesy Viktor Hachmang

For Hachmang, a challenge lay in accurately representing each artist’s invention within only a single panel. “I need to zone into just a small part of the narrative, and then try to suggest the whole world through that,” he says. “Mood is the key word for my narratives. Even when I’m doing comics, the main thing that I am interested in is not so much a head-to-tail, A-to-B type story. It’s about fleshing out the mood and trying to capture this dreamlike atmosphere.”

“Mood is the key word for my narratives. It’s about trying to capture this dreamlike atmosphere”

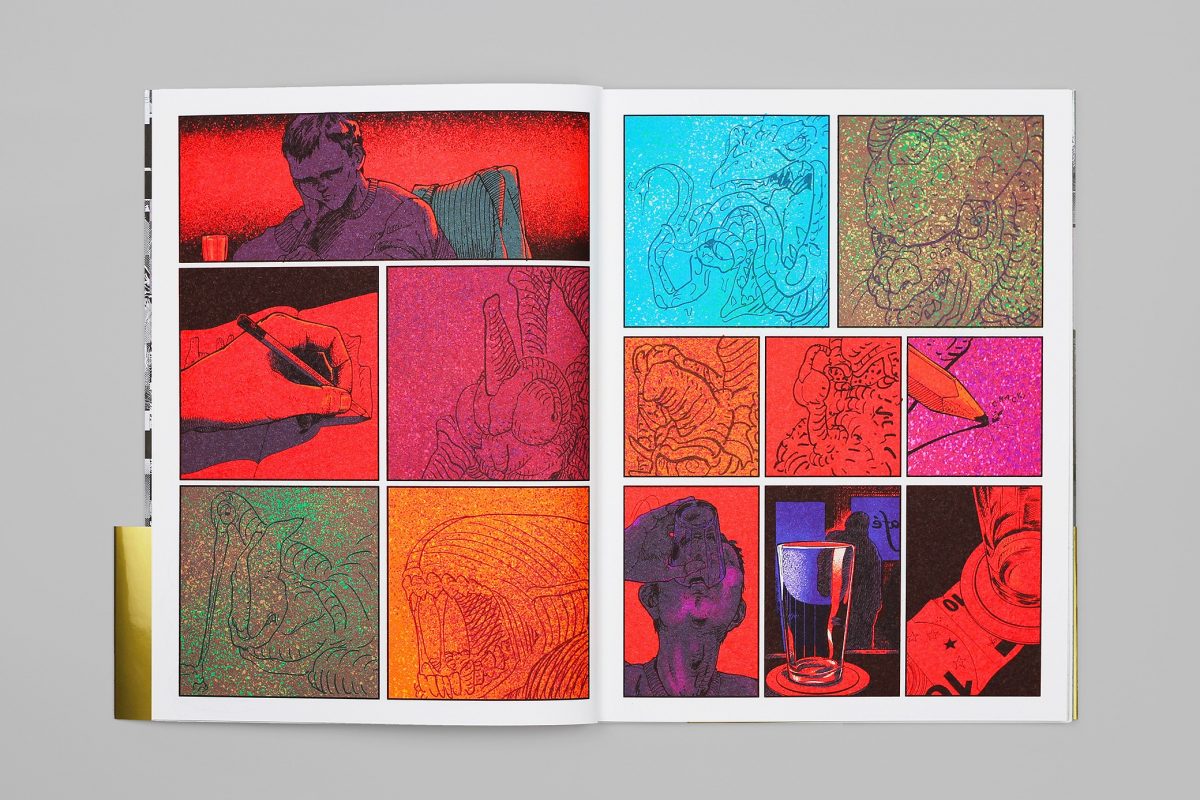

When embarking on a new drawing, Hachmang explains that he will first try out various rough sketches in his notebook. He then embarks on a more fleshed out version with just a pencil, before scanning and continuing the image digitally through retracing all the line work on the screen. “What is important at this stage is that it still feels like something that is handmade. I don’t want anyone to be able to tell if it was created physically or digitally; I think it adds to the mystery of the image,” he says. “When I’m adding colour, I also want it to sit between manual and digital so I use lots of scanned textures to give them a tactile quality.”

In the Elephant feature, a silver spot colour was used throughout to unify Hachmang’s images and to lend a visual flow throughout. “I really love the way it looks,” Hachmang says, noting that it extended his interest in the tactility of printed matter. He also used the colour to nod to Japanese Edo Period panel paintings, in which solid blocks of gold and silver were used to conjure large fields of colour and light.

”I want my images to sit between manual and digital so I use lots of scanned textures to give them a tactile quality”

Under Hachmang’s direction, each scene bursts into vivid life, bringing each artist’s speculative proposal into sharp focus. Yet with global temperatures set to rise by a disastrous 2°C by 2045, the prospect of the end of the world as we know may not be just a fantasy but an increasingly likely possibility. If so, Hachmang’s beautifully rendered, delicately drawn science fiction visions for the future could just come true.

Louise Benson is Elephant’s deputy editor