In Paris, the Palais de Tokyo’s Dioramas exhibition sneaks behind the glass case to trace the invention’s theatrical origins as well as the colonial violence of its eventual institutionalization. Meanwhile, Suspended Animation at Les Abattoirs in Toulouse asks how reality can be visualized in an increasingly digital world.

Entering Dioramas, I’m ambushed by a television screen that has been surreptitiously placed in the left field. A scene from Shawn Levy’s film A Night at the Museum is on loop: the protagonist, a pitiable night watchman (Ben Stiller) is up against the Natural History Museum’s entire collection, brought to life by some ancient spell. “What is going on?!” he demands, banging on the vitrine of Native American heroine Sacagawea while historical US army Captain and Second Lieutenant Lewis and Clark bicker over maps in the background. A resuscitated stuffed bald eagle caws overhead. “I can’t hear you,” she mouths back sympathetically, gesturing toward the soundproof case.

As I move into the cavernous exhibition hall I learn that the first dioramas were not glassy capsules imitating the natural world but glamorous stage sets for elite entertainment, popularized by the in-crowd of the early nineteenth-century Parisian bourgeoisie. Conceived as a kind of proto-theatre and dreamed up by the set designer and painter Louis Daguerre (who later invented one of the world’s first photograph processes: the daguerreotype), it offered a world of dramatized “historical” happenings and mysterious lands that appeared to move thanks to trick lighting, faux atmospheres and dramatic acoustics. Dioramas presents Jean Paul Favand’s masterful nineteenth-century Naguère Daguerre series, in which colourful, semi-transparent canvases illuminated by shifting light dramatically reveal the Brooklyn Bridge stretching across an industrialized East River. I round the bend just in time to witness the eruption of Mount Vesuvius–the molten lava bursts out like fireworks, then trickles back into the angry mountain in a hypnotic, time-defying sequence.

Bleeding across classes and cultures, the diorama became a staple of circus entertainment as well as a new world political campaign. In 1823, just one year after Daguerre’s grand debut, the first diorama opened in London in order to sell a spectacular vision of life in the Royal Crown’s colonies. Bypassing distinctions between fact and fiction, the diorama—literally meaning “to look through”—functioned as a mythic portal that permitted its visitors to exist between worlds, while creating new ones in the process.

Ironically, the diorama lost its magic when the faraway lands and exotic creatures it envisioned could actually be preserved. Around halfway through the exhibition, Dioramas steps back into a modern-day narrative with the invention of taxidermy. The exhibition is quick to call out the problematic themes of imperialism and conquest that form the backbone of the diorama’s move into the museum but also spotlights the environmentalist agendas of celebrity taxidermists including Carl Akeley, who was responsible for the iconic dioramas at the National History Museum in New York. Next to the bronze bust of a grinning ape, it’s revealed that in 1921 Ackley conducted the first scientific study of a gorilla in the wild. It’s a moment of lucidity that undoes the diorama’s real and fake binary, where the desire for alternative worlds catalyzes a deeper understanding of the one we occupy right here, right now.

Some six hundred kilometres south of Paris, inside an ex-slaughterhouse now home to Toulouse’s modern and contemporary art museum, a similar threshold is explored. All summer long, the second floor of Les Abattoirs hosts a selection of avatars: the uncomfortably empathetic creations of nine artists working in the realm of the digital, from Ed Atkins to Kate Cooper, as part of Suspended Animation. Each has a room to itself—the lighting, sound qualities and even carpeting in each room is curated by the artist—creating a surreal fun house that seems to exist outside of a tangible place and time.

Just as the modern diorama incorporates both human and animal figures, the digital realm makes no attempt to distinguish between human and non-human. Instead, avatars occupy an uncanny space between the virtual and the real. In the first room I stand face-to-mouth with Agnieszka Polska’s disembodied floating lips as they spout seductive one-liners while neon waves wash over the screen. It’s completely unintelligible, but the psychophysical effect is profound. Polska’s playing with ASMR, a pleasurable, tingling sensation released by whispers, gentle repetition and certain sounds among other things, which has been a point of obsession on the Internet in recent years.

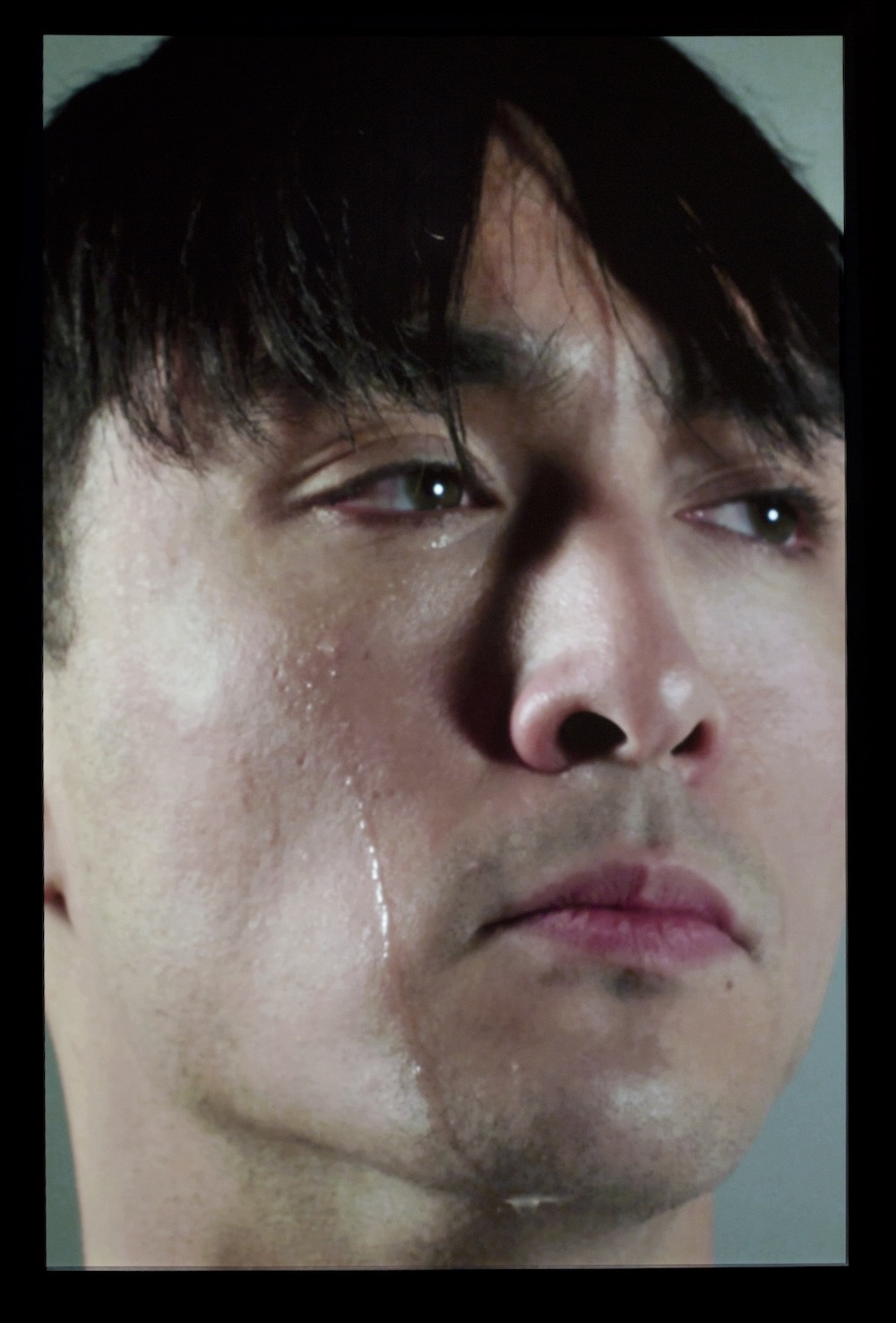

Transitioning into Kate Cooper’s hyper-capitalistic installation RIGGED, the stakes are raised. The digital body, dystopian and predatorial, turns on our own, and it looks threateningly good while doing so. Cooper’s purchased the rights to a computer generated female body–an alter ego of sorts–who runs, stretches and practices her metal-filled smile in HD luminosity that hurts to watch. The next room contains Ed Atkins’s Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths, in which a motion-capture, computer-generated avatar recites a Gilbert Sorrentino poem with a sarcasm-drenched tone that mimics today’s millennial mega-ennui, but still struggles to summon empathy. This uncanny void gives me the shivers, and not in a nice way.

Real time kicks back against the suspended status of VR, too. Josh Kline’s stunning Hope and Change takes on a whole new meaning in the Trump era. The video features a glitching Obama avatar reciting a revised version of the 2008 inauguration speech, written as if Obama had known everything that would unfold throughout his two presidential terms. Exhibited here for the first time post-Trump, it’s stripped of its two back-up screens as well as its kitschy props of plastic eagles and Tellytubby generals. The pitch is off, the mood is somber, Obama’s signature hope has mutated into cruel optimism.

At their core, both Dioramas and Suspended Animation are fundamentally about challenging our perception of reality. They’re also about growing into that free zone that wraps around the world we inhabit: how to own up to those fantastical alternative visions we’ve created, for better or for worse. Glass, whether a computer screen or a vitrine, is see-through, but it’s also reflective. What we encapsulate, memorialize and create, and how these inventions effect us in turn, reveals more about our own nature and desire.

The sweeping expanse of Dioramas’s own “Great Hall” offers a sampling of contemporary art’s response to the invention–from Anselm Kiefer’s Family Pictures to Mark Dion’s gritty Paris Streetscape—all while their popularity continues to wane in history museums. The final act is Kent Monkman’s Bête Noir: a Native American Chief, its central character sitting atop a pimped out Harley Davidson, glitter arrows scattered around, while a cardboard cubist bull—possibly from Picasso’s Guernica—lies defeated on the floor in front of the cool chopper.

As I turn to leave I come across another Levy scene that guards Diorama’s exit like a portal. This time, a fake rock flies from Stiller’s hand, smashing the glass case imprisoning Sacagawea. He’s figured it out. If we want to truly understand the worlds we’ve created—human, animal and other—we need to let them out of their cages.

When they challenge, shock, inspire and intimidate us, we learn more about ourselves and can begin to address the historical blunders of imperialism and fantasies of progress lost to time.

‘Dioramas’ runs until 10 September at Palais de Tokyo in Paris. ‘Suspended Animation’ runs until 26 November at Les Abattoirs in Toulouse.

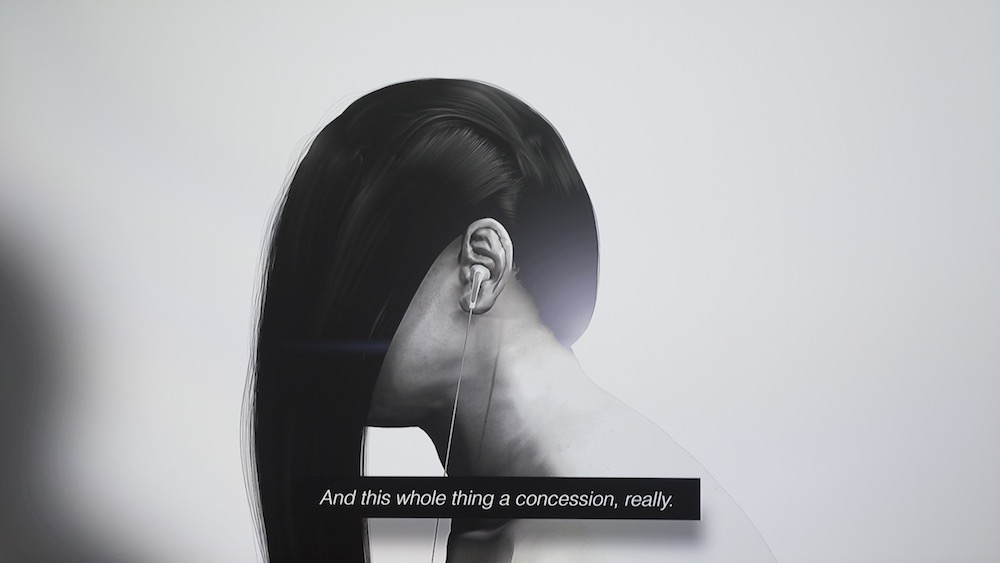

Ed Atkins, Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths, 2013, HD film, 12:50 minutes. Courtesy of the artist; Cabinet, London; Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York; Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie, Berlin

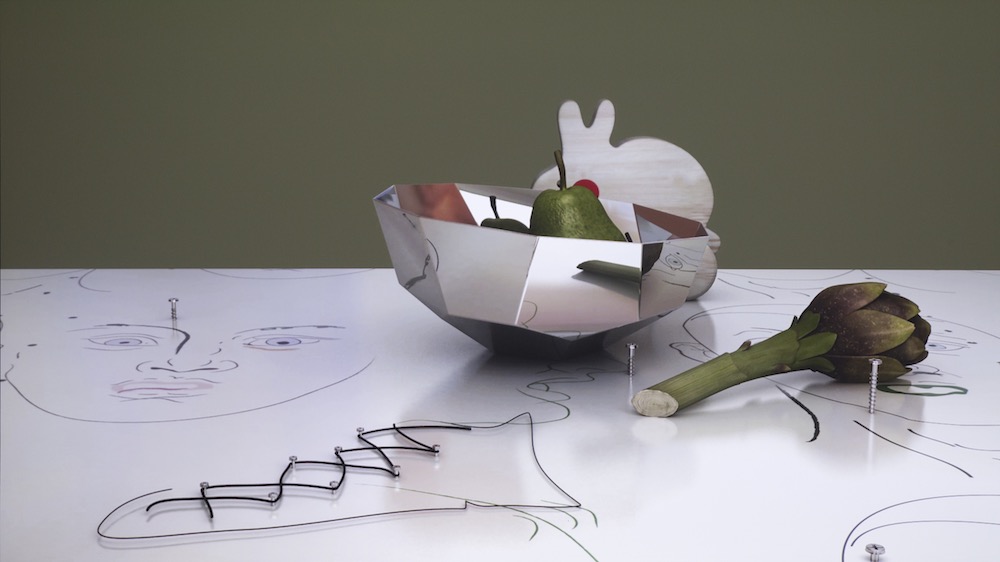

Exhibition view of Dioramas, Palais de Tokyo (14.06 – 10.09.2017) Kent Monkman, Bête noire, 2014. Acrylic on canvas, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Aurélien Mole