Ralph Nauta and Lonneke Gordijn, the duo behind Dutch artist collective Studio Drift, sometimes talk over each other, which in the hubbub of the busy Stedelijk restaurant can make things difficult to follow. The noise and counter-flows of conversation contrast with the sense of wonder that permeates their solo show upstairs, Coded Nature, which fills eight rooms with installations and also includes a new film. It makes you wonder if the collaboration that started when a science fiction fan (Nauta) met a nature-lover (Gordijn) is more discursive or argumentative. “Both,” says Gordijn, just as Nauta offers that it’s “depending on how much we’ve slept”.

Studio Drift have long been known for their technological creations which capture or appropriate the beauty of natural phenomena to stunning effect. Fragile Future, a series of modular matrices of lights shining delicately inside real dandelions, has its roots in a project as old as the practice, which was founded in 2006. The Victoria and Albert Museum purchased a Fragile Future chandelier in 2010, and the Stedelijk in 2015. But new works are different, directly challenging consumerism, delivering sci-fi visions, blurring the boundary between technology and magic—and addressing the individual in the context of the group.

“We’re taking more freedom to express ourselves,” says Nauta. “After ten years we’re finally at a position where we can work on new ideas.” That, as Gordijn says, “takes people, time, money, knowledge”. Nowadays, Studio Drift is a team of twenty, and research is a continuous element of their practice. “It’s not that we take something off the shelf,” Nauta explains. “We literally develop the technologies to make something happen.”

Their technological take on nature is apparent before you even reach the Stedelijk’s first floor galleries hosting Coded Nature. Meadow (2017) hangs from the ceiling at the foot of the stairs, a group of textiles folded around LEDs, which robotically open up as wide as tutu skirts. They look like dahlias, but glow in different colours. In another work, Tree of Ténéré (2017), the leaves of a tree glow through a cycle of colours. A word that has been applied to Studio Drift’s work is “bio-design”, but they’re not sure. “It’s a weird word. The only proper bio-designer in the world is nature itself,” comments Nauta. “Nature is so much ahead of every technology we can make,” says Gordijn, emphatically.

“The only proper bio-designer in the world is nature itself”

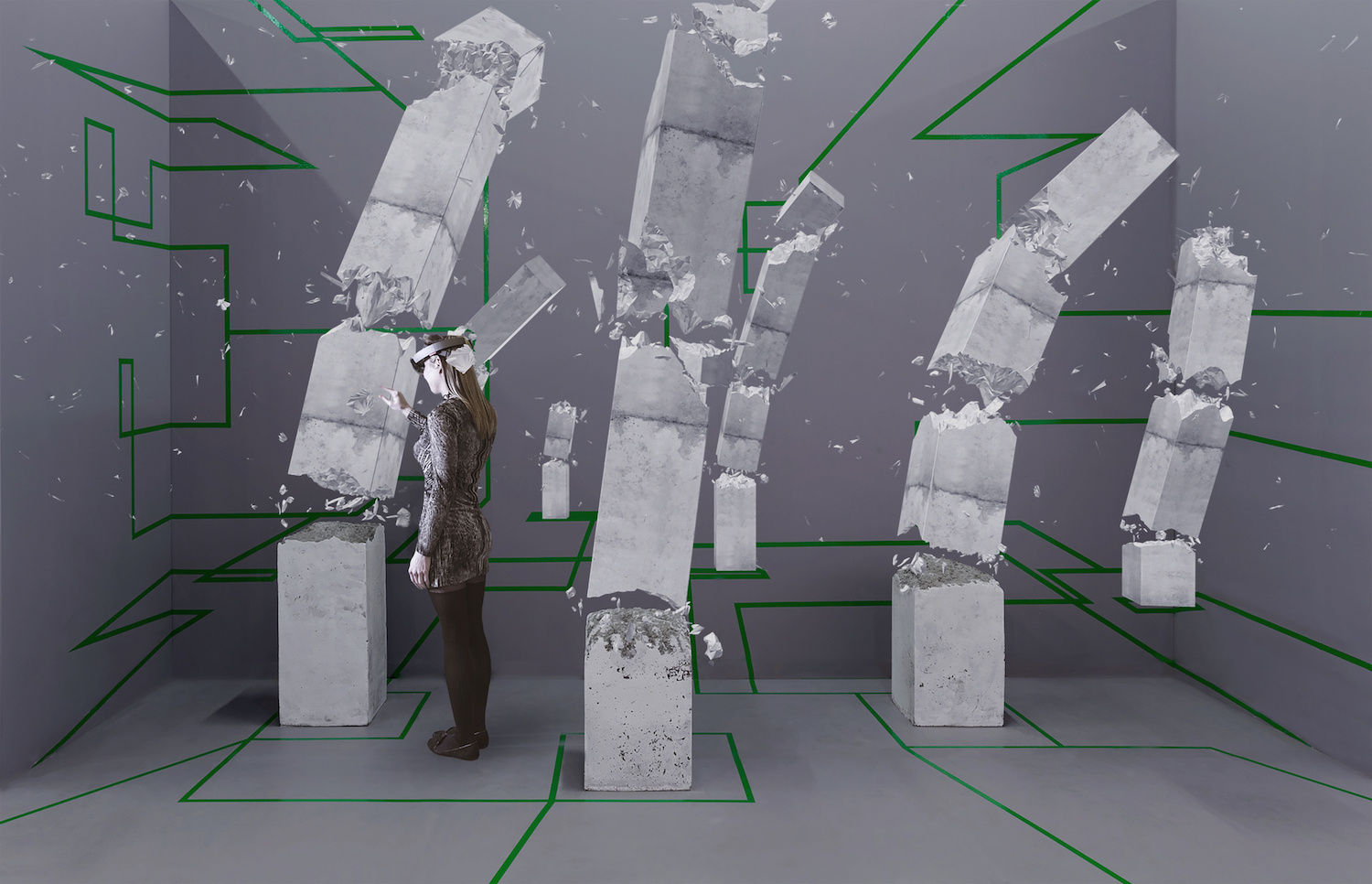

And it’s not all directly inspired by nature. Don a virtual reality headset and an array of concrete stumps become broken columns swaying in an ominous storm, in the enhanced reality installation Concrete Storm, which was first unveiled in New York last year. Another work from the Armory show that becomes a highlight at Coded Nature is Drifter, a four metre-long concrete block, which floats and drifts in the space of a gallery. The simultaneous impressions of extreme mass and weightlessness are mesmerizing. Concrete, they point out, has a science-fiction root in that Thomas More predicted its qualities in 1516 in the book Utopia. Gordijn says it symbolizes the architecture of the landscape humans have created, with its possibilities and limitations. But Drifter does not reveal its technology. Seeing it at the Stedelijk, I remark to Nauta, “You’re a magician.” He merely smiles and says, “Thank you.”

The technology was more comprehensible but its effect no less extraordinary in Franchise Freedom, a “living sculpture” performed at Art Basel Miami in 2017. A swarm of 300 drones, each loaded with an LED, sensors and an algorithm that drove them to self-organize as they reacted with each other, took flight like a flock of birds. At the Stedelijk, we see something similar in Flylight (2011), static glass tubes in which lights create the patterns of swarm flight activated by the presence of someone viewing it. Such group behaviour is also at the heart of a new film, Drifters, made with Dutch filmmaker Sil van der Woerd and shown for the first time in Coded Nature. A concrete block like that seen in the adjacent gallery emerges from a lake, drifts through a pristine forest as it finds other floating blocks and together they swarm above the Scottish Highlands, eventually coming together in a big floating wall. “It’s the block heaven,” comments Gordijn. Drifters showcases breathtaking cinematography, but it is also a story. What’s it about?

The answer, it seems, is freedom. Like the drones in Franchise Freedom, Drifters presents a group choreographed by its individual members, but in the film we start with one emerging alone. That block can be seen as “a new lifeform that is trying to find its purpose in a world it doesn’t really fit in,” offers Nauta. “Is freedom total disconnection from society?” asks Gordijn. “Freedom of being lost, being alone. Or is freedom being in a group and being accepted?” Indeed, are Studio Drift suggesting that we should all come together? Nauta suggests, “You actually have the choice to shape the world as you want to live. That, I think, is the message in all the works—opening up the mind again to almost its childhood, a receptiveness to how the world could function. It’s like dreaming again, and a lot of people are not dreaming.”

“Is freedom total disconnection from society? Freedom of being lost, being alone. Or is freedom being in a group and being accepted?”

If Drifters is ultimately a call for us to dream, the other work that debuts in Coded Nature is more like a wake-up call to what we are taking from the world. Materialism takes a number of manufactured objects, from a VW Beetle car to an LED and a pencil, and breaks them down into their constituent raw materials. On a plinth for each artifact, the materials are mounted as a cluster of blocks, incidentally with the same proportions as Drifter, the concrete block. “What was interesting to see [was] that we don’t know how things are made,” comments Gordijn. “It was a process of de-production.”

Materiality seems to be the exact opposite of Studio Drift’s practice, which centres on production of new works in ever-advancing new media and technologies. It’s yet another step beyond the light installations that they established themselves with, and which they are still glad to receive commissions for. Do they see themselves more as artists than designers? After all, they met while studying design together at the Design Academy in Eindhoven, and have been stars at design events like Salone Mobile. “I’ve never made something functional in my life!” responds Nauta. “Sometimes you get pressured into this category of designer and that doesn’t feel right.” Gordijn states that “the reason we started studying it was curiosity—how the world works.” And that, she concludes, is “why we make things.”

All installation views at Studio Drift: Coded Nature, 2018, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam by Gert Jan van Rooij