It’s safe to say that art critic Jonathan Jones is a divisive character. Never one to shy away from saying exactly what he thinks, he is admirable, really, in an era where “criticism” is increasingly rare—many writers veer towards the politer side of wordery in fear of bridge-burning, offending or simply disagreeing with widely-held consensus around which art and artists are “good” or “bad”.

However, that’s not to say that I necessarily agree with his views; or that art criticism (or indeed any writing) should be a free pass to offend or bombastically bluster about something purely for provocation’s sake. Indeed, Jones has had no shortage of critics of his own: the writer has long railed against the work of Grayson Perry (suggesting in 2001 that his vases should be smashed). Perry’s response was to create a vase, shown at a 2017 Serpentine Gallery show, on which he painted Jones’s description of Perry’s work as “suburban popular culture”. Perry (possibly) deliberately misspelled Jones’s name, as, “Johnathan”.

However, Jones is self-aware about his tendency for barbs. “I… scatter insults more widely than I realise,” he told the Guardian, in a piece in which he went on to scatter more: “Bob and Roberta Smith … has good taste in shirts”; for instance. And, “Damien Hirst gets no apology. He has betrayed us all.”

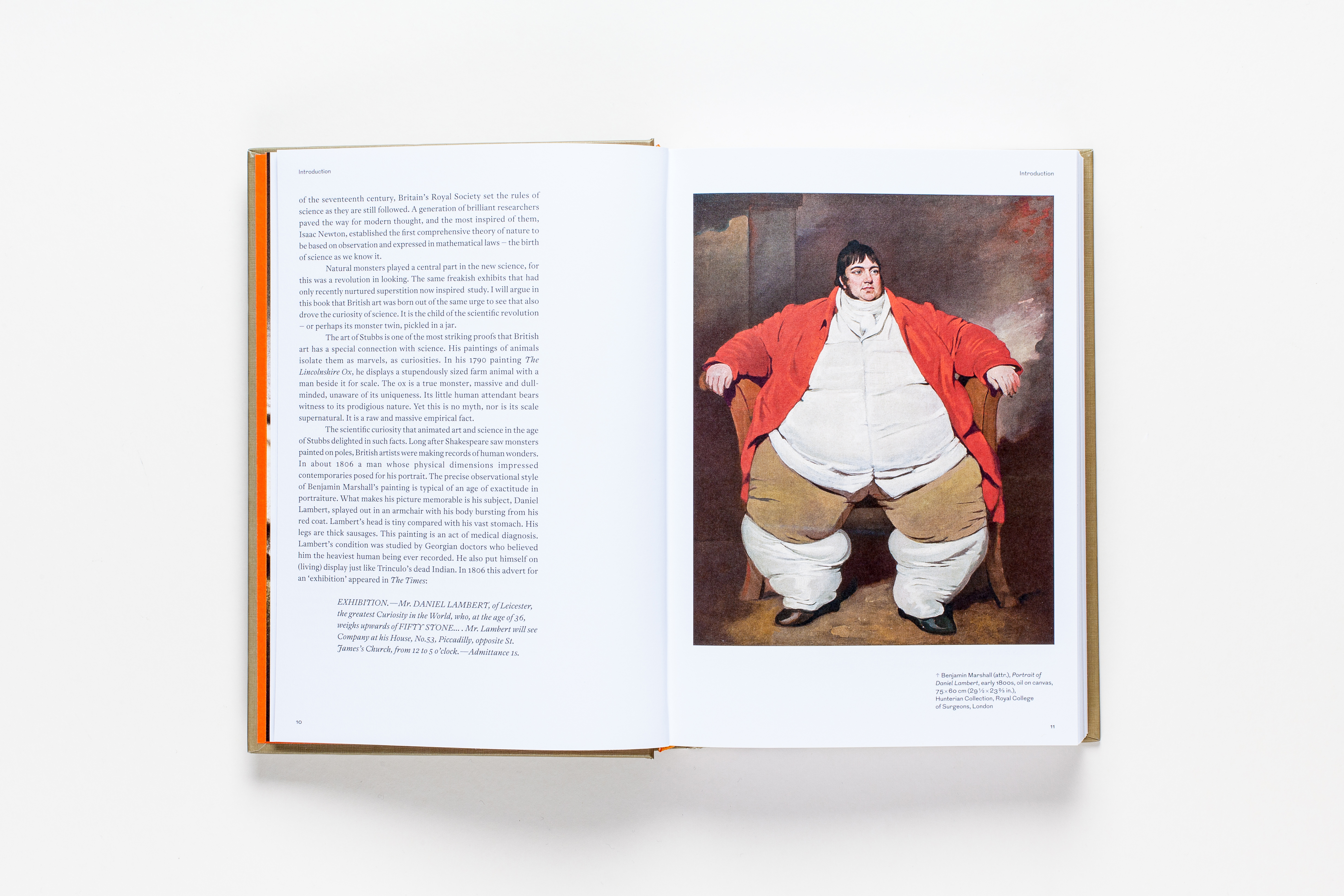

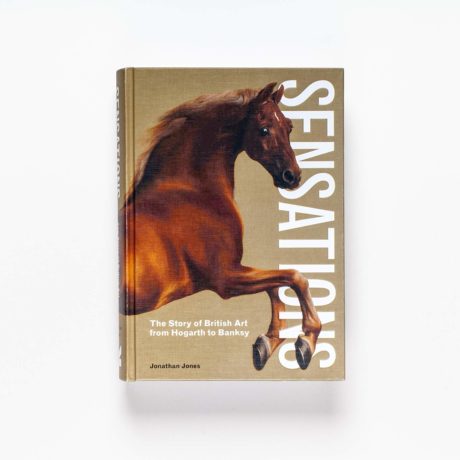

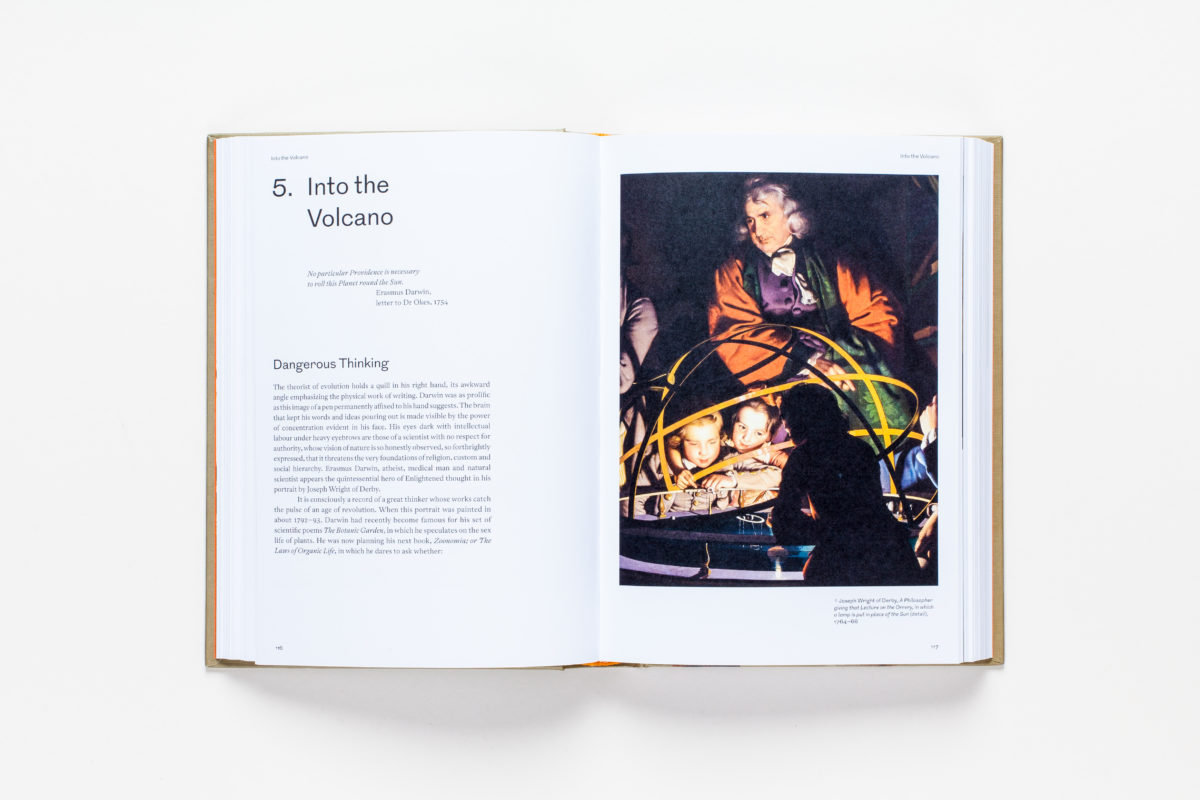

Yet his latest book, Sensations, takes a far more celebratory and measured tone. Billed as The Story of British Art from Hogarth to Banksy, the book is an ambitious survey that spans centuries; aiming to join the dots from the likes of William Hogarth and Thomas Gainsborough to Tracey Emin and Banksy.

The hefty tome traces art through other concepts, such as Newton’s scientific discoveries and John Locke’s “sensationalist” philosophy, which emphasizes the use of the senses as well as the sciences in understanding the world around us. So sure, there are some lofty ideas in here; but below are a few of the more unusual findings in Jones’s book.

1.

Samuel Pepys (and Jonathan Jones) seem to be really into fleas

The opening of Sensations focuses loosely on the idea of the use of light in art. In it, we learn that Samuel Pepys—most famous for his diaries—was entranced by a 1665 book called Micrographia, written by mapmaking pioneer, architect, astronomer, biologist and experimenter Robert Hooke. Micrographia was an early example of using microscopic images in science books, and a pioneering text in terms of merging science and art.

Jones describes the louse and flea in the book in almost romantic reveries: “… these tiny animals… display formidable armour plating, articulated limbs and fierce faces. The flea has hard spiky hairs on its smoothly segment exoskeleton. […] These are not fanciful pictures of dragons or sea monsters. They are patient renditions of real creatures revealed in all their alienness by the power of lenses. These ‘monsters’ are natural and this is exactly what they look like.”

2.

Eighteenth-century London had its very own “hot felon” artistic muse

According to Jones’s book, London’s population during the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries—a “human chaos” of gambling dens, brothels and “overstuffed graveyards”—was rapidly expanding despite the fact that more people died than were born in London each year. Jones describes the capital then as a “sinister playground of marvels”; touching on the “hot felon” of his day, thief and notorious jail breaker Jack Sheppard, who by his fourth prison escape was seen as a sort of good-looking, Cockney working-class hero (he was ultimately hanged). For the art world, he was the perfect muse: the character of Macheath in John Gay‘s The Beggar’s Opera (1728) was based on Sheppard, and William Harrison Ainsworth’s 1840 novel was simply titled Jack Sheppard.

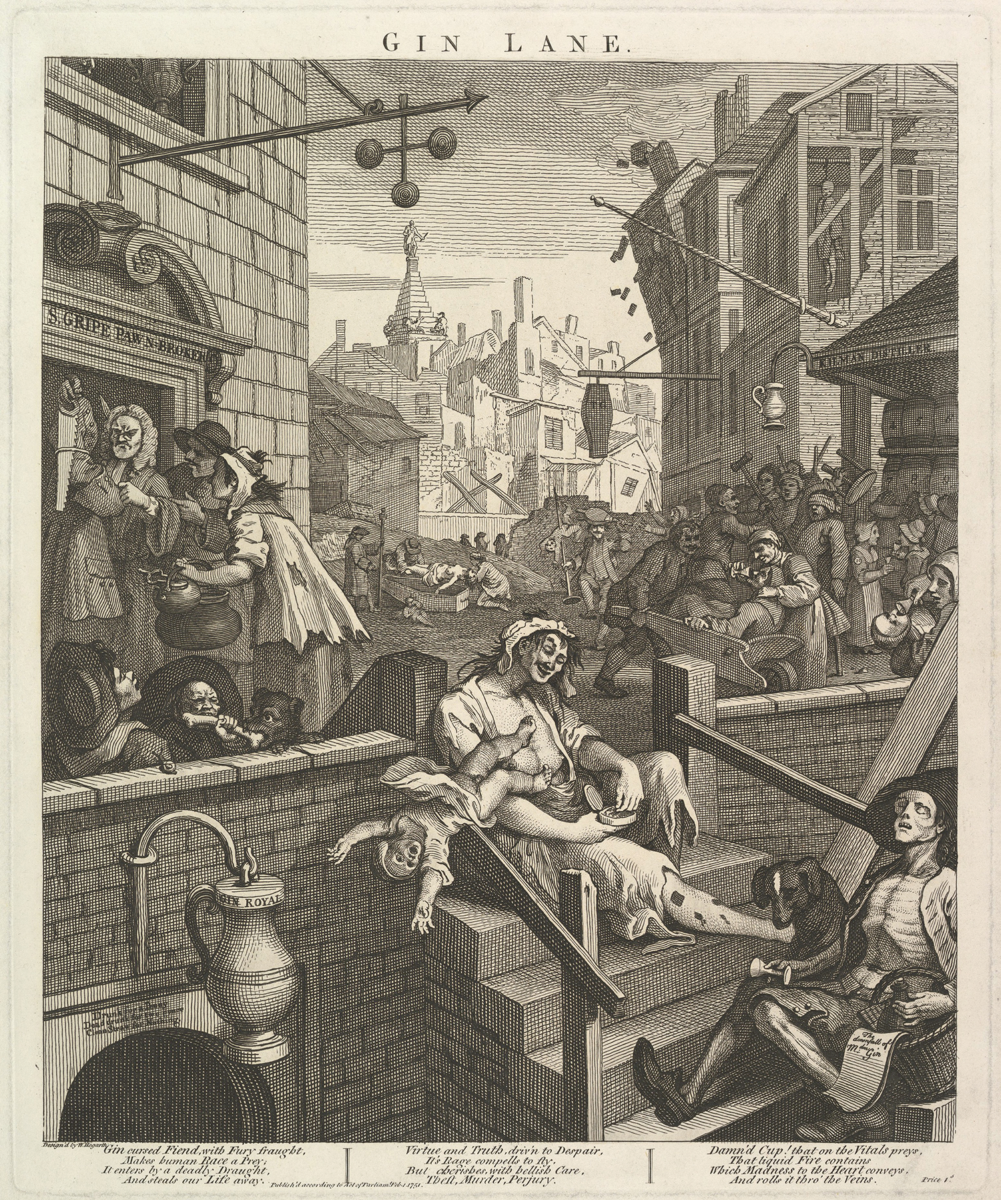

- William Hogarth. Left: The Reward of Cruelty (Anatomy Theatre) from The Four Stages of Cruelty, 1751. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven; Right: Gin Lane, 1751, etching and engraving; third state of three. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

3.

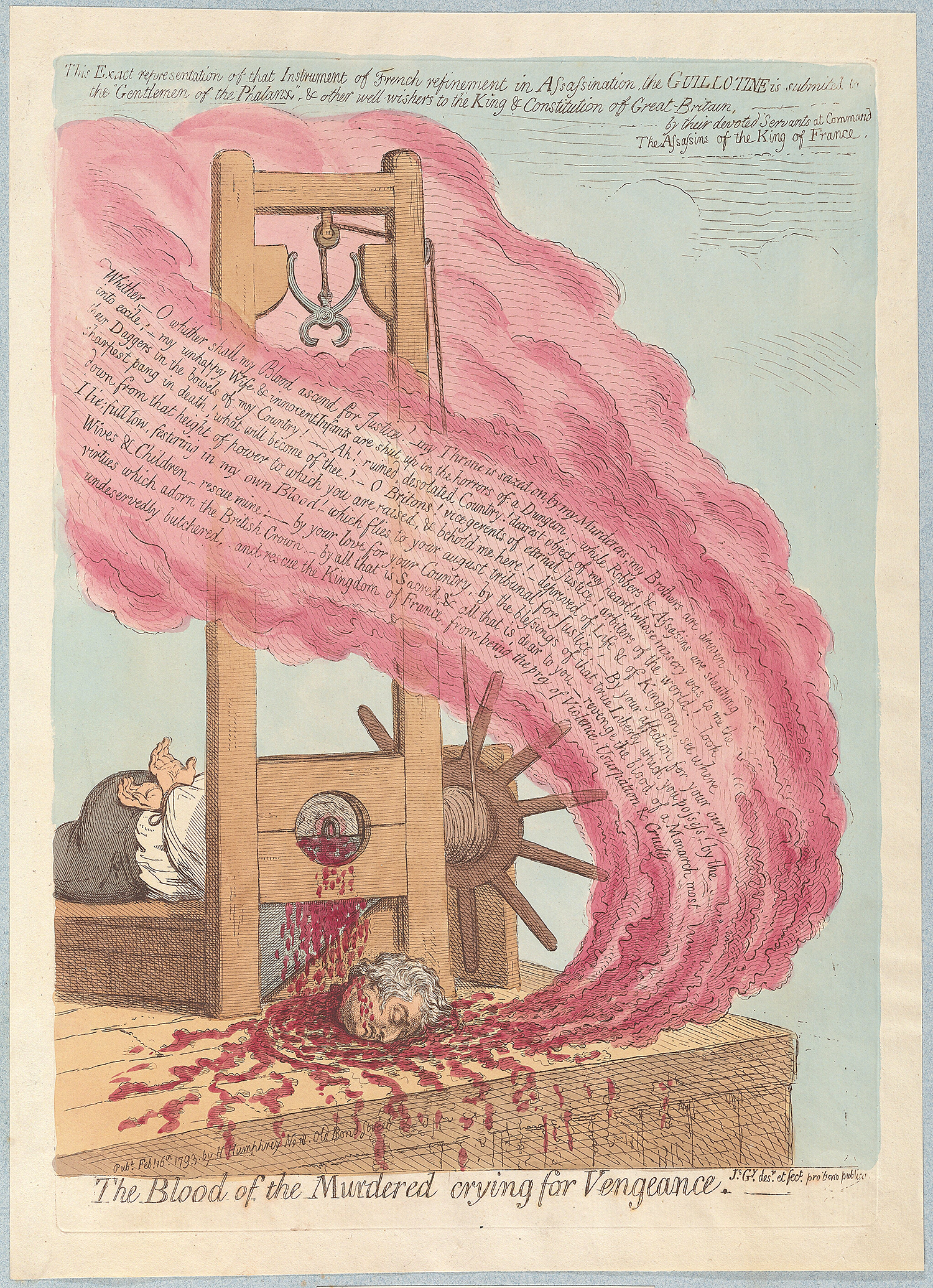

Don’t drink gin, drink beer!

The term “gin lane” has become a shorthand for the sort of piss-dappled alleyways known to anyone who grew up in suburbia when pretty much every drinking establishment closed at 11pm. Gin Lane, of course, is also probably the most famous work by William Hogarth. Created in 1751, it depicts London’s poverty and a cast of characters who are absolutely trollied: like something from a modern-day frat-party, a woman is seen with gin poured into her throat as she reclines in a wheelbarrow; another feeds it to her baby; another is unceremoniously dumped into a coffin. Jones describes Gin Lane as “one of the most powerfully delineated nightmares in European art”, and compares it with the works of Northern Renaissance artists Pieter Bruegel and Hieronymus Bosch.

“Gin Lane plunges into horror yet offers a solution in this earthy life,” Jones writes. “Quite simply, do not drink gin.” He then looks to Hogarth’s companion piece, Beer Street. “A much pleasanter corner of London,” he writes. “Instead of skin-and-bone paupers we see plump, healthy, laughing folk relaxing outside an inn. Everything is reversed. The city looks pristine.”

- Sensations by Jonathan Jones

4.

When Jaws, terrifyingly, came to Brighton (possibly)

In the eighteenth century, Brighton’s entrepreneurial doctors rebranded the declining fishing town as a sort of health destination, extolling the virtues of its salt water—recommending to patients that they not just swim in it, but drink it. George III’s brother, the Duke of Cumberland was a regular visitor, as was his son George, the Prince of Wales. According to Jones, it was this bunch of royal bon vivants that “made gambling, dalliance and high dining part of the Brighton scene”.

But all was not as joyous and healthy as it sounds—at least if a painting by John Singleton Copley, Watson and the Shark (1778), is to be believed. It had been reported in 1785 that a swimmer in Brighton encountered a large tiger shark that “plunged after him with that violence, that it faced itself entirely out of the water on dry land”. Note that the report came a good seven years after Copley’s painting was made. Had his art made such a profound impact that it engendered a sort of false memory syndrome? Jones notes that the image is a very accurate anatomical portray of the tiger shark (a species usually found in the Caribbean). “Perhaps the success of Copley’s painting, like Steven Spielberg’s Jaws in more recent times, gripped imaginations so tightly they imagined a man-eating shark when there could be none,” Jones posits.

- Sensations by Jonathan Jones

5.

What’s Jonathan Jones got against Ruskin?

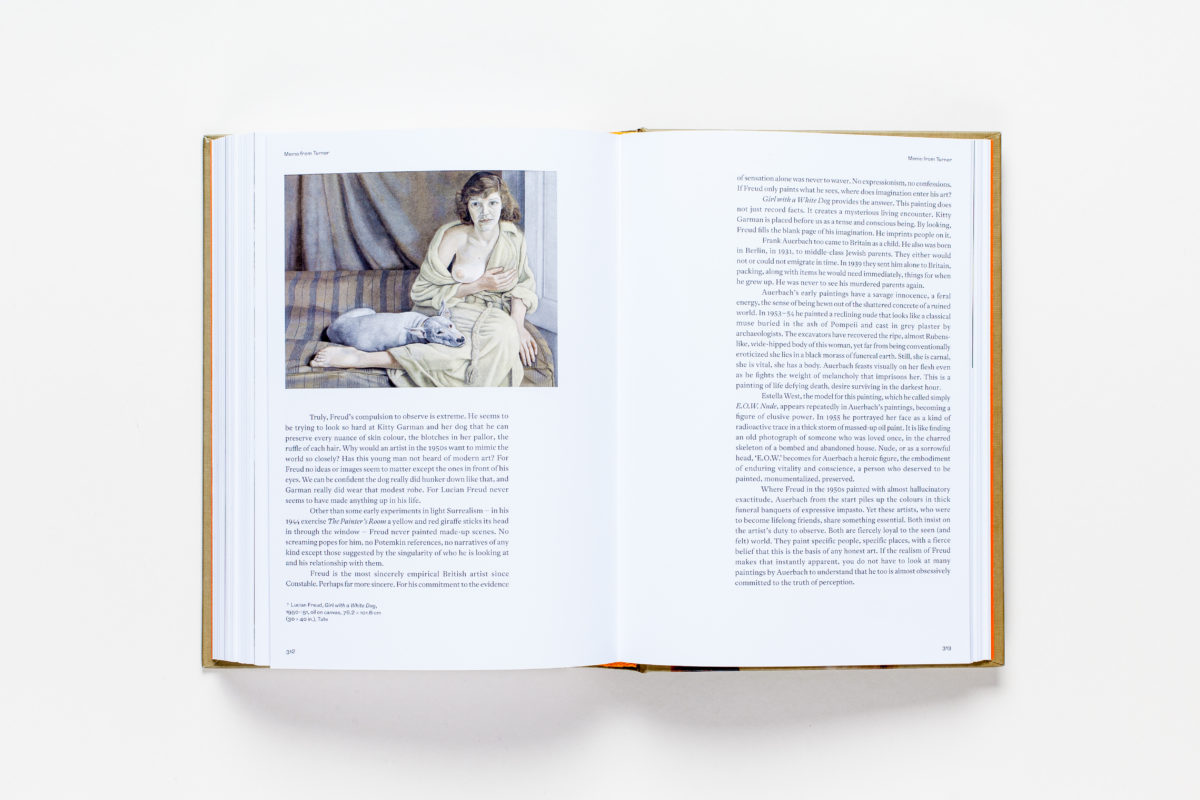

Sensations offers a comprehensive look at the period in the nineteenth century when conversations around the confluence between art, religion and nature were perhaps at their most vigorous. Turner’s paintings paved the way for lyrical, fluid representations of the natural world—radically, he didn’t attempt, as Jones writes, to create the “raw fidelity of what was before his eyes”.

John Ruskin had long been championing the work of Turner (Jones goes as far as to call such devotion “hero worship”). In Ruskin’s five-volume book series Modern Painters, he argued that Turner not only “reveals the truth of clouds, light and water, but that in so doing he shows us the face of God”. Jones writes, “… he does not simply summon up scientific facts to prove Turner’s accuracy. He advances what amounts to a Christian vision of science as the decoding of God’s great book.” Throughout this chapter, Jones emphasizes the “eccentricities” of Ruskin—pointing out that his marriage fell apart since he “failed ever to make love” to his wife.

6.

Victorian morality killed “delight” in art: but did it make it sexier?

According to Jones, the potent combination of Evangelical Christianity alongside heightened “moral scruple” and “high-mindedness” saw the suffocation of artists like Rossetti, whose decorative, gaudy approaches were the antithesis of sombreness and piety. “The moral claustrophobia of the Victorian age surely played a part in crushing visual delight,” says Jones.

Yet this point is soon invalidated in his discussion of Aubrey Beardsley’s work. “Beardsley makes all sexuality look perverse, all his people alien,” writes Jones. He adds that Beardsley himself “confesses to being the most freakish of his characters in a portrait of himself immersed in a vast bed that he drew in 1894. Jones writes that one theory exists that the image hints that the artist was sleeping with his sister. “No one has ever made black and white so erotic,” Jones writes.

7.

Was Walter Sickert the real Jack the Ripper?

Well, in short, no. But the German-born artist was rumoured to be for a time, thanks to his predilection for frequently wearing disguises and deliberately getting himself lost in the busy London crowds. “Some [saw] Sickert’s masquerading as sinister,” writes Jones; clearly meaning a few Londoners of the time put two and two together, made five, and solved a series of murders that now, more than one hundred years later, are still a mystery.