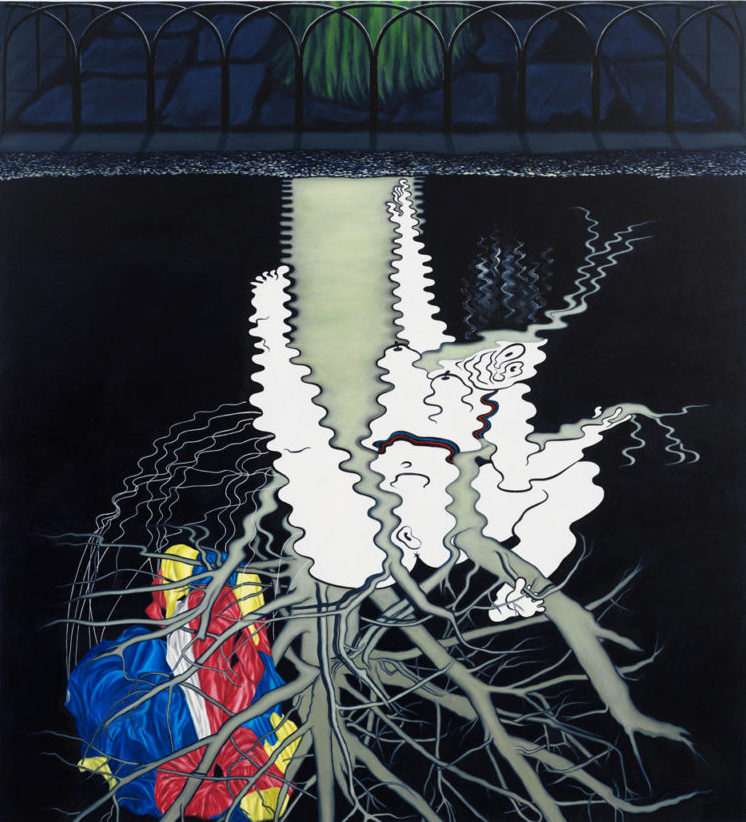

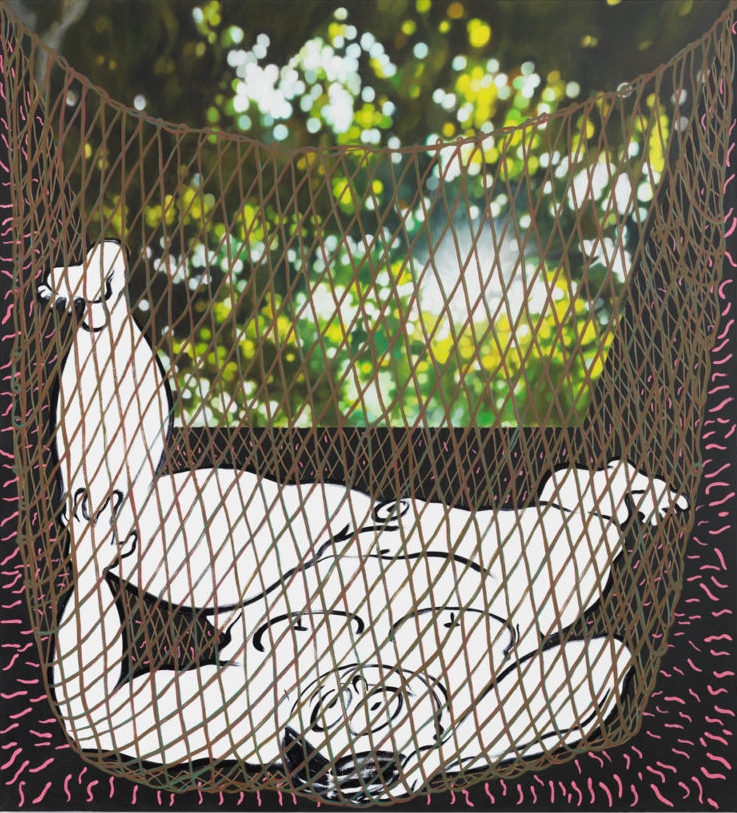

Since 2011, Ebecho Muslimova has led a double life: her own, and that of her sort-of-alter-ego, Fatebe (pronounced “Fat Eebee”), who has manifested through her artwork over the years—initially in the form of thousands of quick notebook drawings, and more recently in a series of paintings, some of which are currently on show at Magenta Plains in New York in a show entitled Traps! Fatebe is both glorious and grotesque; hilarious and unsettling as she settles into a series of strange, often logic-defying surreal scenarios.

Born in Russia and raised for the most part in New Jersey, Muslimova studied sculpture at art school, and didn’t have a particularly easy time of it: she says that during her senior thesis project, she “kind of had a nervous breakdown” and ended up throwing out the sculptures she’d been working on for the whole of her final year. That was when Fatebe came into her own: the drawings Muslimova had been making as a sort of personal joke, and to show to friends, ended up as her final piece when tacked onto the wall together. She passed the course, but decided that she now “wanted nothing to do with the art world”.

For a brief time after graduation, Fatebe went back to being, as Muslimova puts it, “this tragic joke I’m going to do for the rest of my fucking life and never show anyone.'” However, that “immature tantrum” passed, Fatebe persisted and has been not just the central concern of Muslimova’s work, but of her life: artist and subject have a symbiotic relationship that feels incredibly real for a fiction rendered in ink and paint. I spoke to Muslimova about her less-than-great experiences at art school, presenting the female form, the inherent problems with the “fat” prefix and overcoming anxiety.

Tell me more about your experience at art school: you studied sculpture, so where did Fatebe come in?

I had always drawn since I was very young, then in art school, I didn’t draw or paint and I now understand that I did sculpture because I wanted to, on an artistic level, occupy physical space. Fatebe started as a sort of base joke on the back of a notebook, to entertain myself and my friends and offer a sort of relief from art school critiques. I never expected to be so continuously involved with Fatebe: I tried to kill her off a few years ago, just thinking, “Oh God, how many more of these are you gonna do?” But killing her off can’t just happen: she just refuses to quit. By now, it’s a very important relationship in my life—it’s the only thing that I’ve done for about ten years. It’s funny, like the joke became real. I need to keep her, I want to—I’m like her custodian.

“I’m not making fun of someone who has some curves. They’re just her attributes”

With your second solo show at Magenta Plains you’ve moved on to working in oil paint. Why did you decide to make that transition from drawing? How far did it feel like a “difficult second album” of sorts?

This is my second painting show, and I’m enjoying it more now. When I started drawing that character ten years ago I set up these tight parameters and rules for her: one frame, no narrative, black and white, no shading… I had a natural sense that I had to tighten the space in order for her personality to take up more space. Somehow formal possibilities of more freely drawing her would have distracted from her entity. Then I forgot that I‘m the one who set up those rules to begin with.

For years I was like, “I wonder what it’s like to use colour? I wish I could use colour!” I’d sort of made my own prison, then I started to learn painting. I’ve been painting for two years now and I’m really enjoying how to figure out painting with oils. I’m going to do some wall drawings in future; I’m working on another body of work right now for a show in Zurich in March with Maria Bernheim gallery so in my brain I’m on vacation but actually I’m already behind!

How do you overcome those anxieties about showing work, or making new work?

Through Fatebe; it’s this relationship I have with her where anxieties about work are resolved. I feel like I’m always trying to clarify something through her, and when that doesn’t work for some reason it feels like there’s a big misunderstanding between what should be on the page and what isn’t. That anxiety gets resolved by making a Fatebe that’s satisfying to me.

Have you had any backlash about the name Fatebe as an “alter ego” name, seeing as you are a not-fat-girl living in Brooklyn? How far is she really an alter ego of you?

Maybe there were initially conversations about that, but then we’re just talking about “who’s fat and who’s not” and it just becomes so stupid that it falls apart. She is her own thing. I’m actually surprised that it hasn’t come up more, but I think that she’s really a distinct personality: I’m not making fun of someone has some curves. They’re just her attributes—she looks like a lot of people look, and from the point of view of drawing a body, I feel like there’s a reason fleshy women have always been painted. It’s more fun to render—you can do more, it’s more expressive. Fatebe doesn’t speak, so her gestures and her body are her language. I think of her as being more like a self-portrait, but not me—like I’m rendering a different self, but she’s a friend. She’s like a surrogate sister who can do amazing feats that I physically or socially can’t.

“Fatebe doesn’t speak, so her gestures and her body are her language”

There’s been a lot of discussion around the fact that in your drawings of a woman, there’s never a man present, and the idea of challenging how women’s bodies are portrayed in art in the absence of the male gaze. Is that a deliberate stance?

I’m drawing her body, because I’m familiar with a woman’s body, because I have one. So it’s not a purposeful thing: why would I do any other form? There are definitely parts of her that are like me: the creases of her knee, that’s my crease, and that detail isn’t important to anyone except me; and my eyes get really wide in certain situations, for instance. So there are physical similarities. Also, she’s always seemingly on the verge of some anxiety attack, but she’s enduring in it. It’s not like I’m always on the verge of that, but she’s just like an expression of my mental state, so in that way she very much relates to me.