The words “Potato Christ” might be more likely to conjure up images of a miraculous bag of chips than a priceless work of art, but it is just one of the nicknames given to a now-infamous painting housed in a church in Northern Spain. The fresco, originally painted by Elías García Martínez in 1930, had been of little note. Displayed on the wall at the Sanctuary of Mercy Church in the small town of Borja, its audience consisted largely of elderly parishioners, visiting worshippers and the odd curious tourist.

This all changed in 2012, when the eighty-one-year-old local resident Cecilia Giménez took it upon herself to attempt a restoration of the painting. A solemn depiction of Jesus wearing a crown of thorns became… Potato Christ. Many will know the story already, given that it spread from a quiet local news article to worldwide coverage quicker than it takes to rustle up a serving of French fries.

Formerly moisture damaged, the face of Jesus was given a fresh lick of paint but appeared to have been strangely smeared. His beard and hair were melded into one shaggy mane, his eyes suddenly cartoon-like in their side-glance. The mouth sulked downwards, a far cry from the son of God’s original pensive stare. It was an amateur restoration job gone terribly, terribly wrong.

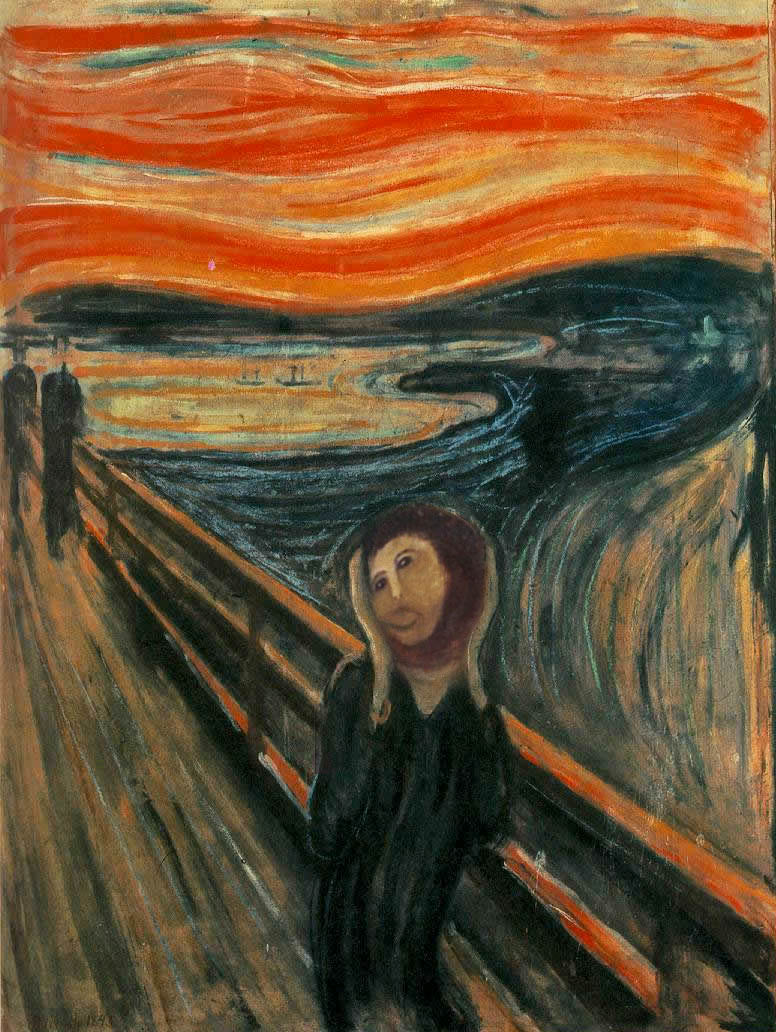

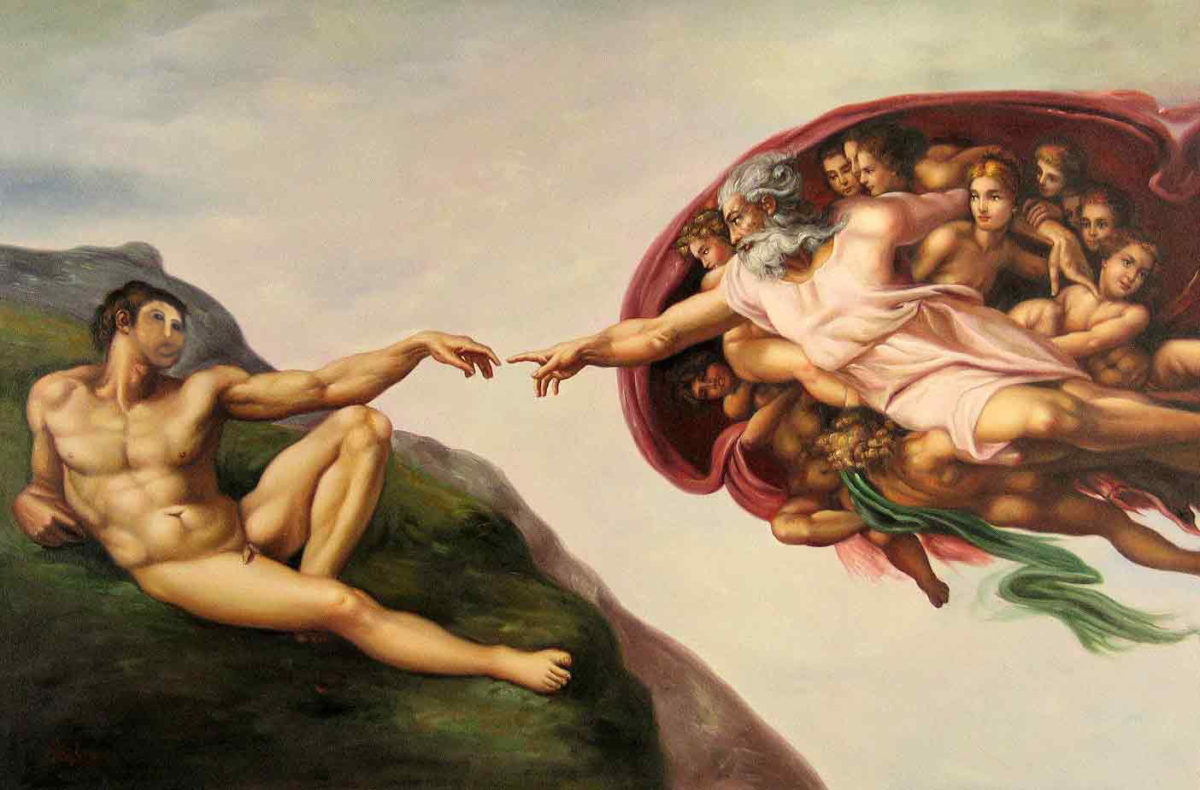

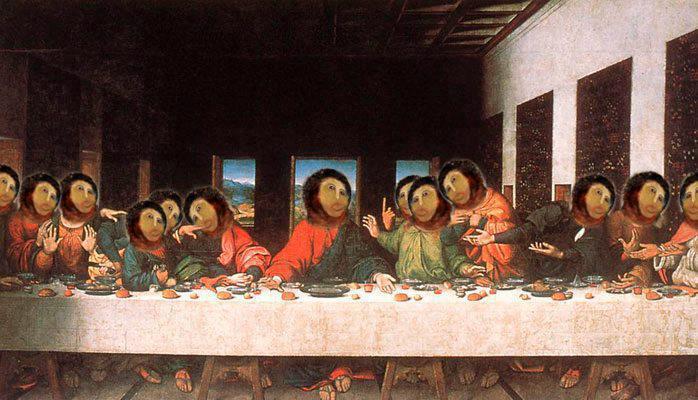

Everyone loves a before and after shot, and in the case of Giménez’s Ecce Homo, the difference between the two could not be ignored. It was an arresting contrast, and one that captured the imagination of a global, and very online, public. International news stories made light of the botched attempt, swiftly followed by countless, ruthless memes. Alternately dubbed “Potato Christ”, “Monkey Christ” and “Beast Jesus”, internet users didn’t mince their words when it came to the restoration. Potato Christ was transposed into everything from the Last Supper to The Scream, his curiously melting face desperately at odds with the best of art history.

It was a shock to the system for the small town (with a population of under 5000), and particularly for Giménez herself, suddenly thrust into the limelight as a global laughing stock. Instagram had launched just two years earlier, while Twitter had been gradually growing over six years. The notion of the viral meme itself was relatively new, and the devastating snowball effect that it could have on the lives of ordinary people was yet to be fully known. The media flocked to the church, and with the whole world watching, Giménez reportedly found herself visiting a psychiatrist to deal with the embarrassment.

“Potato Christ was transposed into everything from the Last Supper to The Scream, his curiously melting face desperately at odds with the best of art history”

Before long, however, the story evolved into something altogether more heartwarming. Audiences were fascinated by the tale of an eighty-one-year-old who brazenly gave the restoration a go, and quizzical visitors began to arrive in Borja in droves. “As soon as people knew that it was Cecilia who had done it, everything changed,” the town’s mayor, Eduardo Arilla, stated. “And this has become a social phenomenon and a pop art icon.” The work (albeit unintentionally) did what pop art does best, appropriating a piece of mass culture and transforming it for a new audience. Move over, Andy Warhol.

The restored Ecce Homo has become a storied part of internet culture. As a visual icon for all the mistakes that each of us have ever made, the image connects on an immense, and yet deeply human, scale. Its impact was immediate and wide-reaching. Within the first year, 45,000 people visited the church, and in 2016, a museum dedicated to the fresco was opened. Souvenirs ranging from pens to mugs raise funds for the community, with fifty-one percent of the proceeds from souvenir sales going to the town’s nursing home, and forty-nine percent to Giménez.

It is a tale with a positive ending, boosting tourism for the region and putting the town firmly on the map, but it’s also a rare example of a meme that translated to real-life change. While Jesus may never look quite the same again (who could ever unsee the piercing gaze of Potato Christ), his botched image stands for human folly, well-meaning initiative and big dreams. Ultimately, we all make mistakes.