Founded in 1987 by three architects, Maoz Alon, Yoav Trifon and the late Reuven Cohen-Alloro, Tav Group was among the first to pioneer green architecture in Israel. They are still leaders in eco-friendly design, but they have always done more than plan and build public and private houses (such as their award-winning, widely-acclaimed Ein Hod house, the first house in Israel to be made of hemp, completed in 2016). Until 1996, they lived and worked in “mushrooms”: small, round houses they renovated on a hillside just outside Haifa, a small community of friends with young children, with a common goal to integrate their work with their lives, both practically and ideologically.

Over the years, they have organized large-scale art installations and public performances, including Café Tav, a temporary performance arts structure that started in Acre in 1998 and now takes place in Jerusalem in August every year, with evenings of dance, music, food and drink (running from 6 to 18 August, with performances every night except Fridays). Their importance in pioneering an ecological, communal lifestyle has not (yet) been fully recognized in the Middle East. They prefer to leave a low carbon footprint. I met Maoz Alon at the architect’s studio, now located on top of Mount Carmel in Haifa.

When and why did Tav Group form?

I have known Yoav Trifon, my partner, since childhood. We were best friends in high school, and during our army service we built, with a bunch of friends, a new kibbutz (a communal settlement) in the Negev—the southern, desert part of the country, not far from Sde-Boker, home of Ben Gurion in his later days. It was in this framework that we absorbed and cultivated our ideas of community life and teamwork, which are still core principles on our social and professional paths.

Why architecture?

It was Yoav who suggested we went to study architecture at the Technion [Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa]. I was scarcely aware there was such an occupation, but Yoav was brought up in a much more culturally oriented environment than I, with an Eames chair in his parent’s naturally-lit, nice modern living room. He also had a notorious uncle who was an architect. Anyway, what was important to me was to work with people and for people. We were hardly past our second year of studies, already taking on occasional shop designs, when an interesting opportunity came our way, indicating that our career wasn’t going to be straight architecture: the Haifa municipality cultural department invited us to make some temporary artistic interventions in a new pedestrian street. It was then that we met the late Reuven Cohen-Alloro, who was a couple of years senior to us and had already finished his architecture studies. What came out of that meeting was our first installation and since then we became a trio and called ourselves Tav Group.

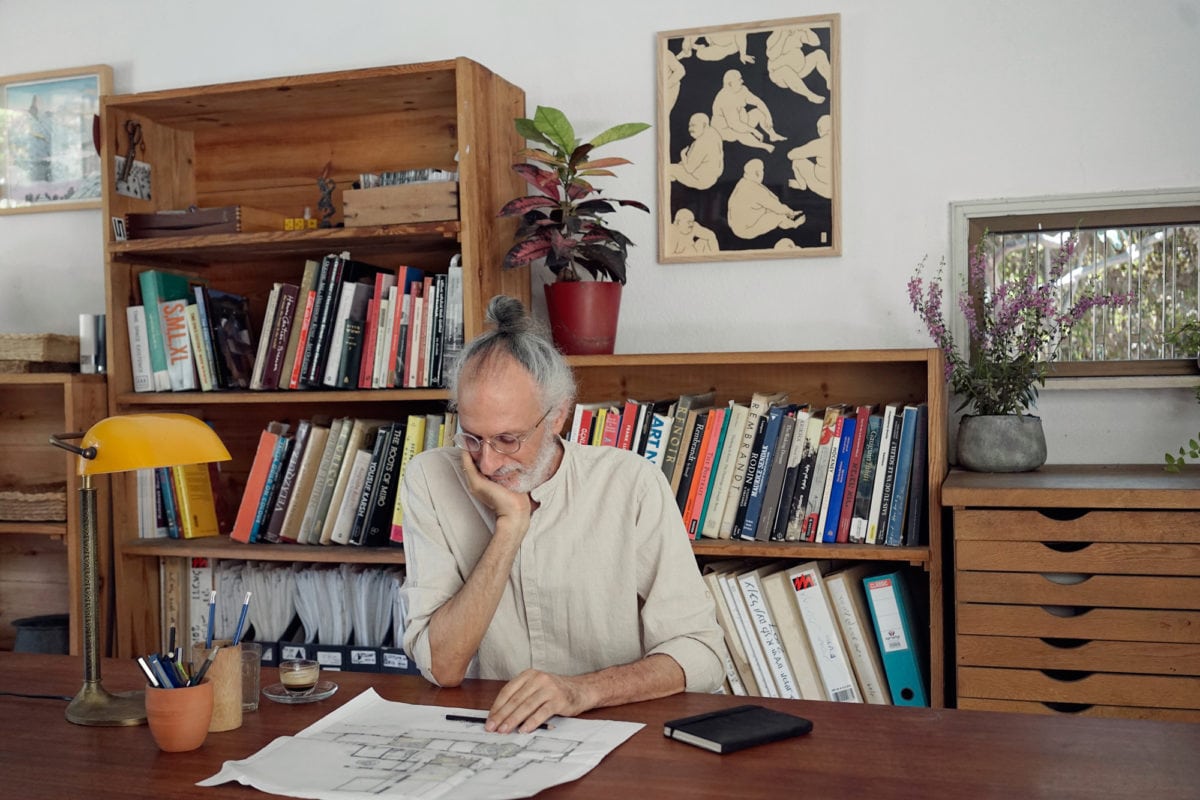

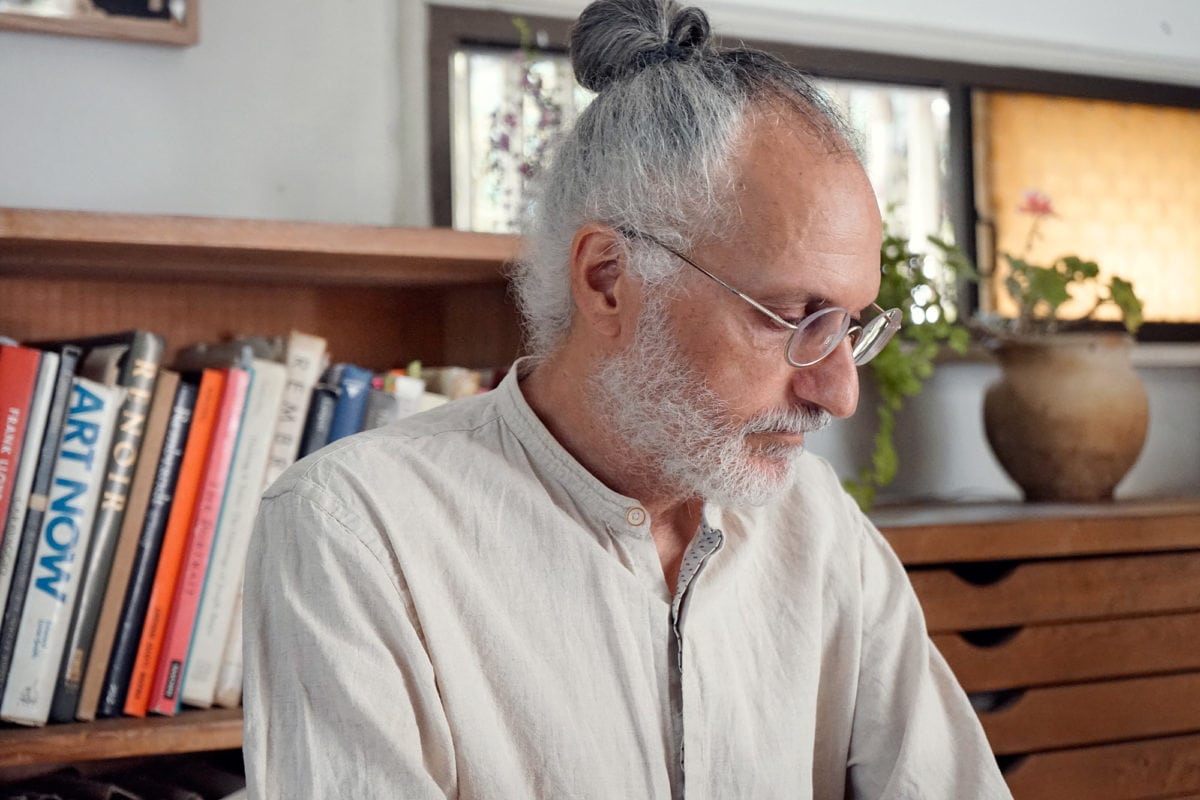

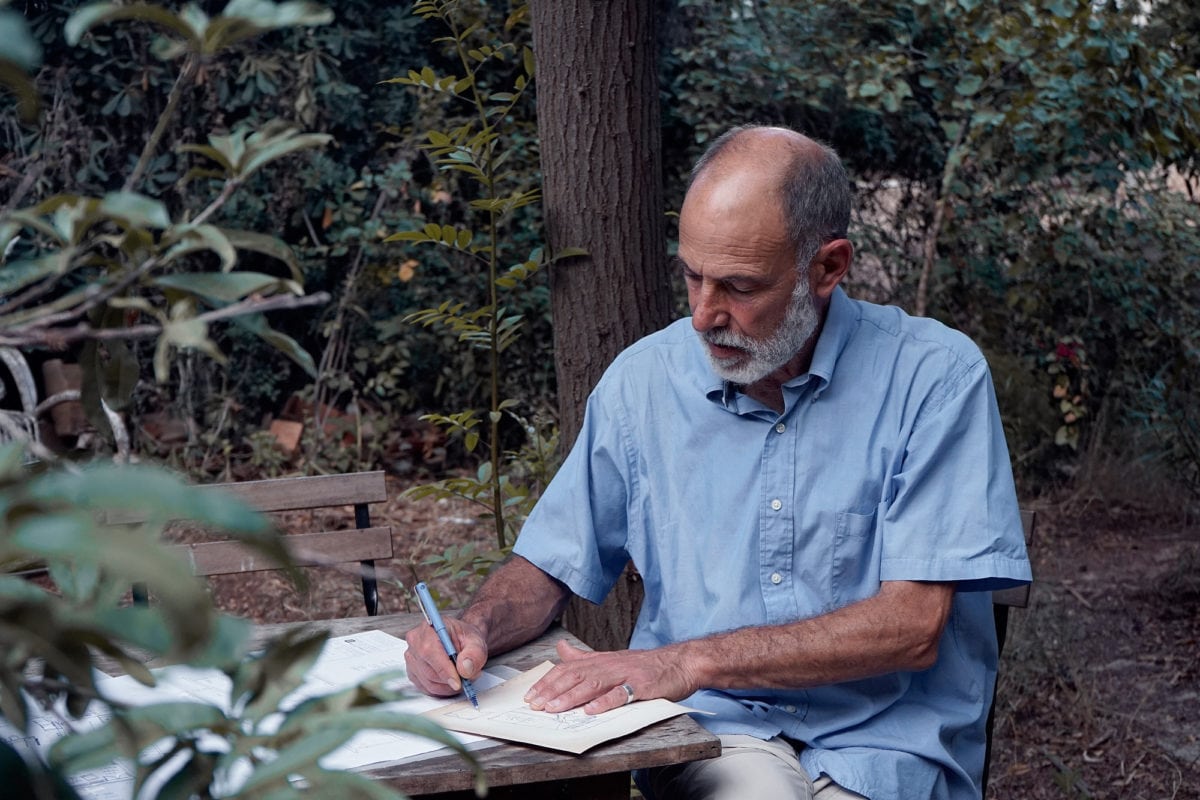

What is a typical working day like at the studio?

Approaching my desk each morning, opening a drawing and exercising the thinking faculty with a pencil in hand… meeting my colleagues, who are my best friends, and exercising the social faculties; exchanging views and advice over a fresh espresso; once in a while a tour to a building site; twice a week a visit to the Technion to tutor a group of students. Who could ask for more?

“What was important to me was to work with people and for people”

How has your own ideology changed with time?

When I come across things we thought and wrote in the early days, in manifestos, essays and interviews, I am quite surprised at how much I can still stand behind them. Over the years we went back to these definitions and although lengthy, cumbersome and utterly imperfect as they were, I couldn’t say I would put them any better today.

We were talking about collaboration and joint creation; about multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary; about a wide range of activities; about being a community and blending home and work life; about the work as an open process questioning the borderline between doer and spectator; about the continuity of the design-execution work process; about working on site with attendance to its subtleties, and about sustainability and engaging in reconciling action…

How has that made its way into the work you’ve done?

Our first steps were less strict in using non-natural materials, for instance. We call this period the plastic era, where we were tempted here and there by this unfriendly material’s bright colour and light weight. There was also a shift in focus from designing museum exhibitions to “proper” architecture. Some of the change was undoubtedly due to the untimely death of our friend and co-founder, Reuven, nine years ago. Apart from the shock and the overall blue shade it drew over everything we have done ever since, Reuven, of the three of us, was more inclined towards earth art and installation, and naturally we miss him and his singular contribution. Now we are a team of five most of the time, and this may be a good time to mention the younger generation currently working with us, who are becoming more and more significant to our work: Dalia Kramer, Amir Erez and Yuval Sherban, who recently joined us.

In terms of Israeli architecture what you do is quite distinct and unique, both in terms of style and materials. Yet there is so much ugly architecture all over nowadays.

Ugly architecture is hardly an exclusive Israeli invention, though, it must be admitted, it is regrettably prevalent over here. To follow Louis Sullivan, when form does not follow function (which includes the proper application of material), we fail to see beauty in it. And when a place is stripped of its past and no longer reflects its natural evolution, it is more apt to go astray and lose its appeal.

The ethos of the young state of Israel, of “making the desert bloom”, conveniently ignoring and many times deliberately obliterating whatever was here before, though perhaps imperative for the purpose of survival at the time, caused environmental havoc and a cultural void. Together with the prevailing modernist fashion—that paid too little a tribute to tradition—and the poor excuse of being a poor country with urgent basic needs, here is the sad result: grey, dreary, repetitious buildings, not very becoming. But the housing environments that are being built today are even worse. It seems like the street is out of the vocabulary, together with the square, the inner court, the shop, the colonnade and the passage. We are rapidly approaching the horrendous state where the only place to interact with your neighbour is inside the elevator of the H shaped apartment tower and the arena for any broader interaction with society is nowhere other than on the electronic media networks!

I feel the same looking at what is springing up in the neighbourhood I live in, in East London.

We were lucky to receive quite wide acclaim lately for our ecological Hemp House in Ein Hod. But I could sometimes hear an inner voice whispering: how ecological can a private house on an acre of green land be? Should we not build denser dwellings within existing urban concentrations?

I answered myself (since miraculously no one really posed the question to us), but some arguments might be brought to our defense: not all rural homes are negative to nature. Some even benefit it, if built and lived in in the right way. After all, we are part of nature, originally. As so many private and low-density houses are still being built (the majority of mankind still lives in them), responsible for so much ecological damage, it is imperative that we relearn to do it right. And this house is trying to set new standards to help minimize this damage. We must keep the rural lifestyle that is the origin of our civilization alive for future reference. So we might look at it as an act of cultural conservation, and this includes reengagement with the beautiful, the pastoral, naïve, primal beauty.

“I hold the profoundly outdated romantic view that we are here to do good and to enjoy it and that beauty is entangled with the good”

“For us, performance has been the ultimate link between art and life”

Coming into the political sphere: what are the problems you face building on land in a place where it is so contested?

Is there a piece of land on this planet which has not been subject to conflict and struggle? We try our best to indulge in action which is healing and recuperating for all, regardless of race, color, sex, creed or species.

There is no work that makes me happier these days than a project we are designing in Jordan for a Jordanian customer. I believe the key to peace is in the hands of the people, and the more there are direct interactions between people, the better the chances for a better future. However, we do not take on projects in settlements beyond the 1967 borders (the green line), in order not to give any hand to further complication of the political situation, which seems to be consistently pushed towards a regrettable impasse by powers grander than us.

Is it possible to encourage more people to build in a more ecological way?

It certainly is possible. Most people would prefer building ecologically. They understand the advantages of health promotion and comfort of use. They would of course readily welcome the savings in electricity and water too. They are even aware of the global ecological crisis threat and would avoid severing it if given such a fair choice. And it should in no way be more expensive to build—it requires very simple materials and technologies. But as long as conventional building is not ecological, ecology will never have the upper hand. There is much work to be done in gradually diverting the mainstream toward the ecological path.

At the moment you are installing the temporary structure for Tav’s annual performing arts event in Jerusalem, Cafe Tav, running in August. How was it conceived?

For us, performance has been the ultimate link between art and life; the arena where these two have a greater chance to mingle and merge. As architects in training and practice, we know the agony of satisfaction postponement; building takes time. So we can easily appreciate the immediate interaction and instant reaction we get here. Café Tav is a good example of how our various fields of action can support and enrich each other. The scaffoldings were brought here from the world of construction. The inner courtyard is an architectonic feature. The performance is temporary, bringing to life a whole architectural ambiance. So it’s also a test case in a transient matter, towards architecture, which would be more solid and permanent.

All images courtesy Tav Group