In Joanna Pocock’s Surrender (2019), the British-Canadian writer recounts her two-year stay in the American west, where she crosses paths with a slew of ecological agents—from MAGA animal trappers to trans rewilders and forest-dwelling ecosexuals—each with their own understanding of the Earth’s ecology and their place within it. When she finally returns to London, equipped with an intimate understanding of the ever-changing landscape of the west and a new vocabulary to match, Pocock wonders: “Should the naming of things arrive in tandem with our observation and understanding of the interaction between these things?”

As Elvia Wilk suggests, naming is an act of power: to name is to pin down, to fix, to categorise—and categories are “notoriously inflexible”. Paradoxically, naming allows us to get closer to the things that exist outside of the spheres we inhabit, even while it has the capacity to reduce our empathy towards those things. In seeking a better relationship with the natural world in an era of increasing climate disruption, perhaps we would be better off communicating through toolkits rather than language—by listening to the planet with all our senses.

“Naming allows us to get closer to the things that exist outside of the spheres we inhabit, even while it has the capacity to reduce our empathy”

Two exhibitions in London attempt to build a multisensory bridge between human and more-than-human worlds. This is no small feat in the fallout of the pandemic, where shared experience has been reduced to cupped hands under sanitiser dispensers and 2-metre-wide isolation chambers. But in the same way that abstaining from naming things can generate a near-infinite possibility of meaning and novel communication, perhaps the temporary suspension of sensory experience caused by Covid-19 will multiply its power upon returning.

Earth Eaters, curated by Cole Projects at the artist-run Hoxton 253, dials up soil to something that can be felt, smelt, and even consumed in an effort to expand our understanding of this component of the Earth’s crust. “In the prevailing paradigm of our present-day culture, soil is taken for granted, worse equated with dirt,” notes the researcher Aliya Say in her exhibition essay (in Surrender, Pocock laments a similar fate in her suburban Canadian upbringing, where soil and its millions of microecologies are regularly uprooted to build more uniform domiciles). By going back to the basics of how soil feels under one’s feet or smells after the rain, she suggests, we might become attuned to see the millions of non-human worlds it contains.

“William Cobbing’s video becomes an absurdist ritual, emphasising sensation over logic”

Bringing together 18 artists and collectives united by their interest in the medium of soil, Earth Eaters offers up a variety of paintings, sculptures and video works that challenge conventional classification, in pursuit of a non-anthropocentric vision of the Earth. Stepping into the gallery, visitors immediately encountered Byzantia Harlow’s Psilocybin (The Sediments of Sentiments): a towering psychedelic totem made from bronze, jesmonite, ceramics, soil and crushed crystals. The more you stare, the more this sticky, womb-like creation gives way to sensory understanding: lips, breasts and mushrooms erupt from its layered surface. In the opposite corner, a video shows William Cobbing cooly slashing open a gargantuan mound of clay encasing his head. As bursts of supersaturated ceramic glazes spill from his incisions, the video becomes an absurdist ritual, emphasising sensation over logic.

Next is a bubbling bog: pond soil, clay, peat, and water comprise Timo Kube’s Untitled Bog (Container #2), one of the many DIY ecosystems produced by the artist in his studio. Peering into the glassy abyss, its resin-like surface transforms into a living, breathing material as micro-organisms flutter and skirt around the circular tub. Nearby, Petrichor, a scented installation by AVM Curiosities’ Tasha Marks evokes its musky namesake through Geosmin, a chemical produced by bacteria in soil after rainfall.

“These are visions of a post-apocalyptic city that seem to confirm everything wrong with humanity’s urban focus”

Architectural aluminium paintings by Charlie Wade; a laser-engraved slab of slate by Trystan Williams, and Kathryn Graham’s brutal chunks of flaking concrete come at the same subject from the different angle: these are visions of a post-apocalyptic city that seem to confirm everything wrong with humanity’s urban focus. Video installations by The Institute of Queer Ecology and the Ebinum Brothers root the exhibition back in the body while reaffirming the significance of care and alternative thinking in constructing an equitable multispecies future.

South of the river in Peckham, the non-profit arts organisation Proposition Studios presents Terra Nexus: a monumental exhibition of 25 artists who question humanity’s relationship with the biosphere. Together, they fill Proposition’s warehouse are 17 “labyrinth artist worlds” through which Terra Nexus unfurls. Propagated fungi, Lao-carved fruit, gargantuan concrete worms, a live scorpion, sensorially-attuned sedum succulent suits and an AI-enabled painting are just a few of the creations on offer.

Many of the artists in Terra Nexus take the city as their starting point. Commonly conceived as the end of the road for natural life—a place of architecture, caustic pollutants and eradicated biodiversity—cities are also unavoidable hallmarks of human civilisation, both present and future. For Rebecca Bellantoni, Cristiano Di Martino, Amanda Lwin, Catriona Robertson, and duo Wumzum & And Is Phi, the city expands beyond its harsh anatomy of concrete, steel and glass to become a site that is both dystopian and utopian: a soft, organic space of memory.

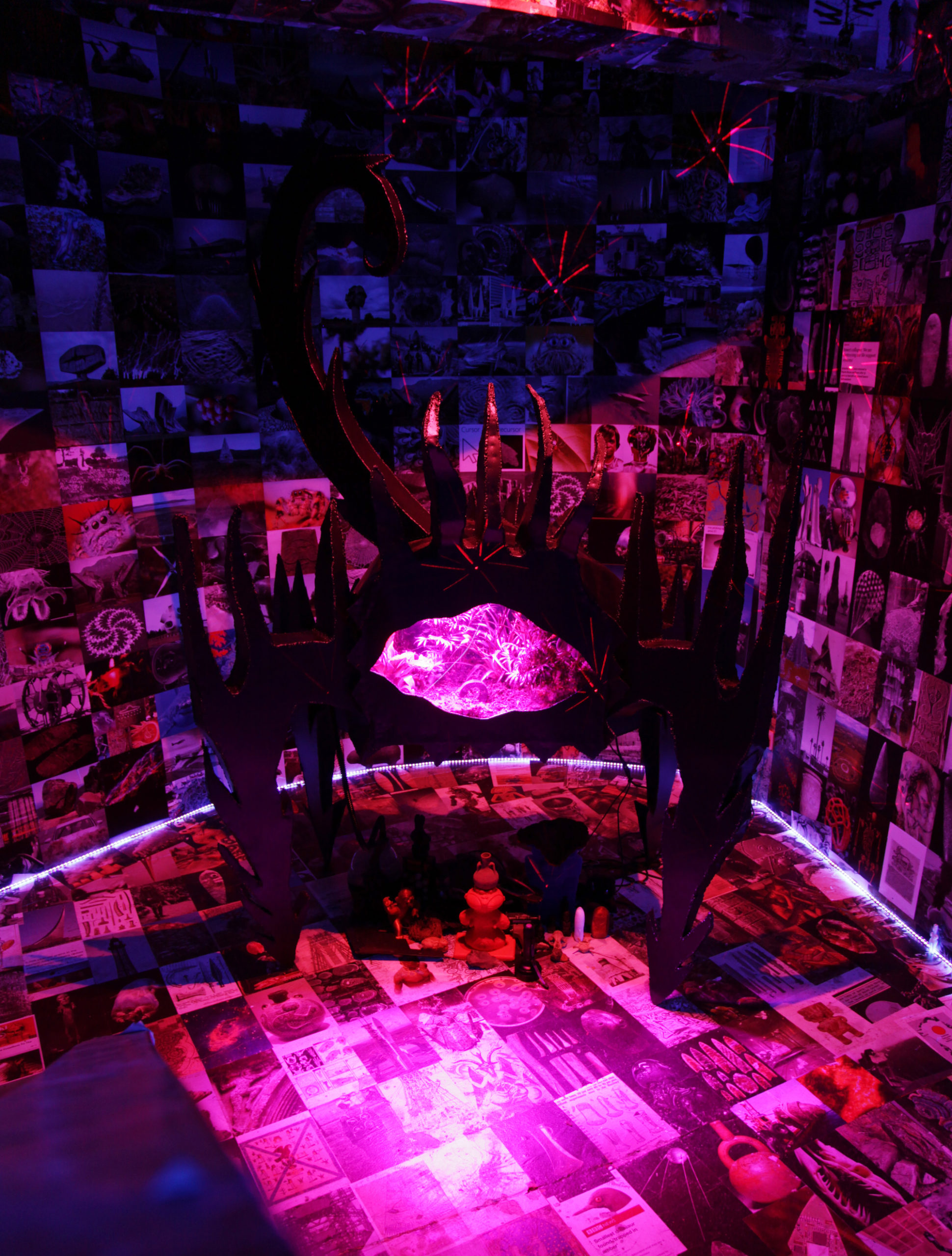

Others engage head-on with the ways technology has tainted our relationship to nature, as seen through the evolution of industrialised agriculture in the 21st century. Wyrd Codex: the Last Hope Hotel by Sol Bailey Barker is a neon purple-lit room plastered with over 10,000 found images linking nature, ancient artefacts and technology. At the installation’s centre is a welded steel sculptural habitat housing an endangered scorpion. Meanwhile, Jack Warne’s AI painting, suspended in a space resembling an agricultural storage facility, flitters psychotically between sounds and visuals uprooted from their source, rendered meaningless in this industrialised data swamp.

“In this space, the capacity for novel experiences lays the groundwork for new ways of thinking about our relationship to the natural world”

While Earth Eaters intends to generate new meaning for soil through a shared medium, Terra Nexus allows its artists to spin off into their own universes of sensory encounters. The result is less an overarching idea than a gradual unsticking of dominantly held understandings of nature, ecology, and humanity’s role in the climate crisis. In this multisensory space, the capacity for novel experiences seems to lay the groundwork for new ways of thinking about our relationship to the natural world—and each other.

The Spirit of The Beehive, a honey-yellow world conceived by international group Food of War, lies at Terra Nexus’ heart. It offers up a hyper-sensory presentation of the relevance of bees for global ecosystems. “The bee apocalypse is not speculative fiction,” cautions Food of War. “It is a rapidly unfolding reality that will affect the way we eat and how we survive.” In this installation, the artists ask visitors to use their senses in order to nurture an intimate interspecies connection with the endangered insects. Through this shared experience—more so than any exhibition text or scientific study—we can begin to develop a framework of care for a world in which the survival of other species runs parallel to our own.

At the end of Surrender, Pocock, already burned out from her return to London, flees the city once more for an ecosexual convergence in Washington state. “The striking thing about the ecosex movement is its insistence upon looking forward,” she reflects. “In their eyes, social change is needed to envision a planet fit to be lived on. Unlike so many ecologically-based movements, their thinking is not misanthropic—it celebrates humans, rather than wishing them dead for their ecocidal ways.” Likewise, Earth Eaters and Terra Nexus mine the nameless communication of the senses in order to envision a more-than-human ecological future—one that is as hopeful as it is necessary.