A day before Thanksgiving, an American Holiday, I have only recently started celebrating in its bastardised form of Friendsgiving, Ed Bereal grants me a career highlight with an interview where he peels back on possibly one of the most influential and interesting art careers to come out of the West but also takes me on a tour through his beautiful house where he now lives with his wife and fellow artist Barbara Sternberger raising horses, and doing what he has done for the greater portion of his career: creating art, and passing on knowledge now no longer at the University of California or Western Washington University where he once taught but in art classes organized by his wife here in his house. ‘‘We’re about 12 miles from the Canadian border.’’ Bereal shares with me warmly. ‘‘My wife and I bought a farm up here, getting out of Los Angeles. And we are in a rather rural area. We bought this property because of the barn, which was a large building that we could convert to studios, shops and workspaces. So it worked out pretty well. We’re very comfortable.’’

Today, at age 86 and with the iconic moustache that has followed him for most of his time in the limelight, Bereal’s eyes are as sharp as his perspective as he shares with me that he has historically never cared for exhibitions. ‘‘I’ve never been one that has either hunted down exhibitions for myself or paid a lot of attention, except for a couple of friends whose work I get invited to see. I don’t pay a lot of attention to the art business. Let me put it that way. I am very much into art as an activity. I’m not that knocked out about the art business.’’ Exhibitions and the commercial art world have never been the focus of Bereal’s career anyway- which is why his decision to exhibit at Basel Miami is so significant. His art has been described as a ‘disturber of the peace’ while the artist himself has been described as ‘the most important activist artist you don’t know’ by Hyperallergic, but Bereal who has witnessed, worked with and helped shape the biggest art-meets-political-activism moments of the last half a century wants to be described as a landscape artist. ‘‘I’m both a political cartoonist and a landscape artist’’ Bereal tells me when we talk about how he has been described in the media. ‘‘In the sense that I am working with the social-political landscape that I’m living through daily. So the landscape I’m living through right now has informed my art, or as the landscape 10 years ago, was informing my art and totally another way. So it takes me a while to make a piece. So that I can’t pop about every day, but I am taking note of what’s going on right now. And my question for myself is, can I in some way, encapsulate what’s happening right now? manipulate it, put it in art and put it forth.’’

Ed Bereal may be one of the people who was seemingly born to do this – he told me his mother had told him that when he was born, he crawled over to a pencil and started to draw. His parents were active participants in the late 20th century Harlem Renaissance where Black artists and musicians would come into Central Avenue to play and even though by the time Bereal, was born in the late 1930s, the Harlem Renaissance had ended, it played some role in his interest in art and experience. By the 1950s, Bereal gained admission to Chouinard Art Institute to study art history in the late 1950s and studied privately with John Chamberlain for the majority of the 1960s. Soon after, he became the toast of the art scene, touted not just as the next big thing but the big thing. Reaching heights was almost unheard of for a black artist in the 60s. Unfortunately, this meant the artist was soon disconnected from the Black community he had come from. ‘‘I have had an awful lot of help. And a lot of support in the art world. I was. I was picked up by what I called the Major Leagues before I left art school. And I was busy being an artist in America and enjoying all the fruits of an artist who had great potential and was on his way up. I was getting a lot of applause at the time.’’ This would all change when Bereal found himself face to face with a machine gun on his way out of a bar on a 1965 evening.

From August 11 to 16, 1965, the Watts riots would shake Los Angeles as Black people protested for amongst many things high unemployment rates and racial discrimination. The riots remained the worst until the Rodney King riots in 1992 which impacted nationwide conversation on segregation. Ed Bereal at the time, toast of the art scene in every sense of the word, was cocooned off in privilege, unaware of the political realities until he walked out of a bar into a machine gun pointed at his face. At this moment, Bereal recalls that the largest impact this had on him was that it forced him to examine how and why he was shocked. He remembers thinking that he wasn’t supposed to be surprised, the only reason he was surprised, he insists, is because he had not been ‘on the job’. Swayed by privilege, he had been almost disconnected from the very community that once fueled his authentic self – a thing core to his practice. Upon surviving the encounter, Bereal’s practice would forever change.

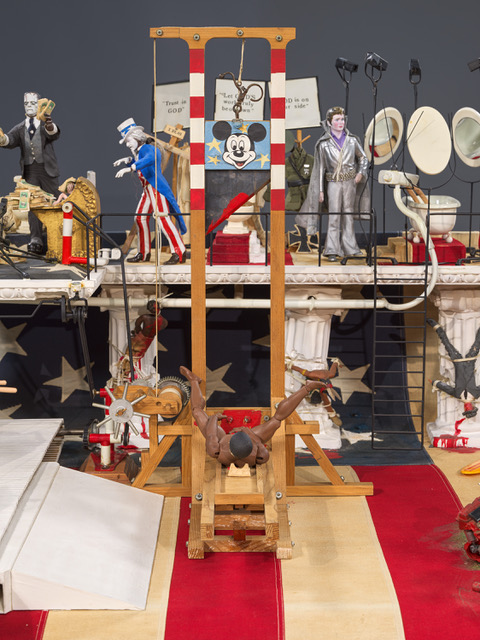

‘‘I went back home and started writing. And I ended up trying to write a play about my experience and my awakening. The play that I was writing got so complex, that I needed to build a stage set that would reflect what was going on in my world, and a stage set that would reflect the power structure, the middle class, position and the whole scheme of things, the ghetto, and its position, and the whole scheme of things and how these all related to one another. The power structure, the middle class, the lower class, the class system, racism, sexism, all of it.’’ Needing a bigger stage to show his work, Bereal got to work building a stage set. The result was America: A Mercy Killing. The piece marked a turn in Bereal’s career. The response to this was such that even after being acquired by the Smithsonian, Bereal shares it was vandalized by a staff member who likely didn’t agree with the politics. ‘‘When I left somebody on the staff of the Smithsonian, attacked the piece and vandalised it, and broke a bunch of stuff. They didn’t like the politics. What happened was, the picture that you probably saw is the picture of the damaged piece. And that’s it, they have recently gotten some funding to repair the piece. And it’s gonna be on exhibit for one I’m told in the next couple of months. But the director of the Smithsonian, when he made a statement about the piece, that what amounted to the fact that this piece would never go on exhibit, as long as he was the director of the Smithsonian.’’

The director who made this statement, according to Bereal, has recently passed on and arrangements are currently being made for America: A Mercy Killing to be put on display at the Smithsonian for the first time.

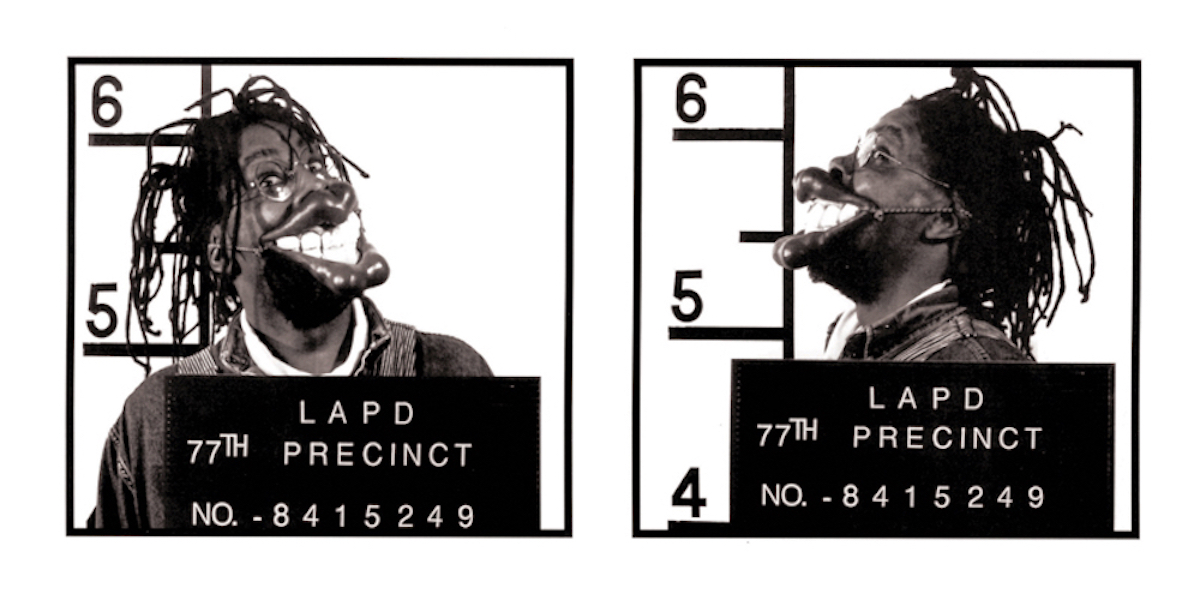

America: A Mercy Killing is far from Bereal’s only work to get backlash. Not long after being radicalized by his experience at the 1965 insurrection, Bereal began working on the Bodacious Buggerrilla, an acting collective that at some point opened for the likes of Richard Pryor often considered the greatest comedian of all time, and was on PBS for a total of ten days before being pulled for being too much for casual viewing.

Almost three decades later, Bereal looks back to the Bodacious Buggerrilla which was founded in 1968 in a Black Studies class at UC Riverside, with the fondest smile saying ‘‘The Bodacious Buggerrilla was probably the most creative circumstance that I’ve ever been involved in. Partly because it wasn’t just my creativity that was being tested, but I was part of a kind of a collective, a group of people who were not, who would never describe themselves as being artists. The Bodacious, according to Bereal, contained strangers, couples, housewives and students all coming together to make a statement by use of shock, satire, and humour to explore the environments they found themselves in. ‘‘We work primarily in the black ghetto, of Los Angeles, which is huge. And we became quite well known because we were worth, we were kind of the voice of the, of the, of the neighbourhood of the community. And we had a quality of the outrageous that made our consumers happy. And we also were a mirror of the committed community and, and and the culture. One person described the bodacious as both a mirror and a window. A mirror that made many of our audience look at themselves, as well as a window through which to see much of the rest of the world. It was a fantastic group of people doing some pretty fantastic stuff.’’

The Bodacious Buggerrilla would come into seemingly great fortune when they got commissioned into a series by PBS. Unfortunately but still a testament to the guttural truth the collective spoke to power, they were cancelled just ten days after being aired – not as a result of poor quality – Bereal noted that their work and talent and quality were constantly praised even in the conversion through their end on Cable TV. Bereal, a fan of Beyonce’s use of her Superbowl performance in 2016 to push the conversation into an area the mainstream society found uncomfortable still believes there are modern ways to push the conversation to uncomfortable but needed directions. Speaking on the possibility of a return of the Bodacious Buggerrilla in modern times when I asked him if the reality of Youtube and less monitored services would make it more possible today, Bereal isn’t against the idea and fully looks forward to the possibility. Just as he looks forward to more artists using their platforms to push the conversations into important albeit uncomfortable directions. ‘‘Now some young rappers need a political education. They have the microphone And maybe they have the microphone because an establishment gives them the microphone. Possibly because their politics are so underdeveloped. Other artists are speaking truth to power and, and to the degree that they think they can. But I would suspect that my recommendation would be that money is not everything. And you do owe even your consumers, you owe them the truth of where you came from.’’ Bereal says this with the empathy and understanding of someone who has once lost his way, disconnected from the authentic self that Bereal shares is integral to creating art.

‘‘Are you familiar with winos? People who drink wine.’’ Bereal asks me, and when I say yes, he goes on. ‘‘Here, in the States, they hang around the liquor store. And their whole life is devoted to a bottle of wine. Otherwise, I know that you used to, I always loved talking to those guys, because they’re our version of philosophers. But this one gentleman told me, I’m not gonna say that you’re lying. But you sound like me when I’m lying. And I think looking at art is the same way, you can tell pretty much when somebody is very highly influenced, if not copying other artists, or AI, if you can tell whether they dug down deep into the kind of thing that they’re trying to do.’’ Bereal has been passing along lessons on art for most of his six-decades-long career, but today, at 86, the lesson he learnt when a machine gun was pressed on his face when he realized he had become disconnected from the social community, the people and the identity that fuel his authentic self, remains the most important for him to impact. And on that Wednesday evening – morning for him – Bereal shares them with me, ‘‘I think we’re all born with an original self, or an original, authentic self. And because we, as we drop out of our mothers, we drop into a social culture of one kind or another. That’s there to tell us who to be, and what to think, and how to act. And we lose the original aspect of ourselves. And that’s where an honest art comes from. And I would say to a young person, there’s, even though everybody’s in your ear, telling you all kinds of things. You better get in touch with yourself. I would say that to anyone. But certainly for sure to the young artist, who is trying to find out what he or she wants to talk about.’’

Words by Desmond Vincent