On the day that I meet Eddie Peake, Nike has just released an advert, “Nothing Beats a Londoner”, depicting neighbourhoods from Brixton to Dalston to Tottenham and beyond in a celebration of London’s diversity. The video is circulating online, and has been praised for its well-observed depiction of real London life, from all-night corner shops to Morley’s Fried Chicken, a surprising feat for a global brand. The people, places and rhythms of London have always run through Peake’s work, bringing his performances, paintings and installations to life as he holds a mirror up to the city and reflects on his own personal history within it. Born and bred in north London, his latest exhibition, Concrete Pitch at White Cube, is his most direct confrontation yet with the city that he calls home. The concrete pitch refers to the recreation ground in Finsbury Park where Peake grew up, which was used as a playground, a sports field and a meeting place for people of various ages, classes and ethnicities. A central installation snakes through the gallery, Stroud Green Road, named after the high street that runs through Peake’s childhood area.

Both of us grew up in London, and as we sit down together we share our thoughts on the Nike ad. I am intrigued by how evocative some of the otherwise unremarkable spaces become when depicted in the film. The everyday experience of picking up a pint of milk in the corner shop is transformed into something that connects us all, and into something to be celebrated. “It’s a very quotidian experience of London and they’re really representing it as this glorious thing, in that advert, and I loved it,” he agrees. “That is, in many ways, what I’m trying to do with this show. My performance embodies the daily routine.” Peake has long experimented with performance art, from a now well-known second-year presentation at the RA Schools in 2013, in which naked men played five-a-side football, to his choreographed routines for naked dancers shown notably at The Curve at Barbican in 2016. Peake himself is present (fully clothed) for the duration of this exhibition at White Cube, following a scheduled routine. He moves between various constructed spaces in the gallery, including a private office, and is occasionally visible through a small window. “It’s very unremarkable, but that’s what I wanted it to be,” he explains. “It’s a play on a quotidian experience of life, and the city.”

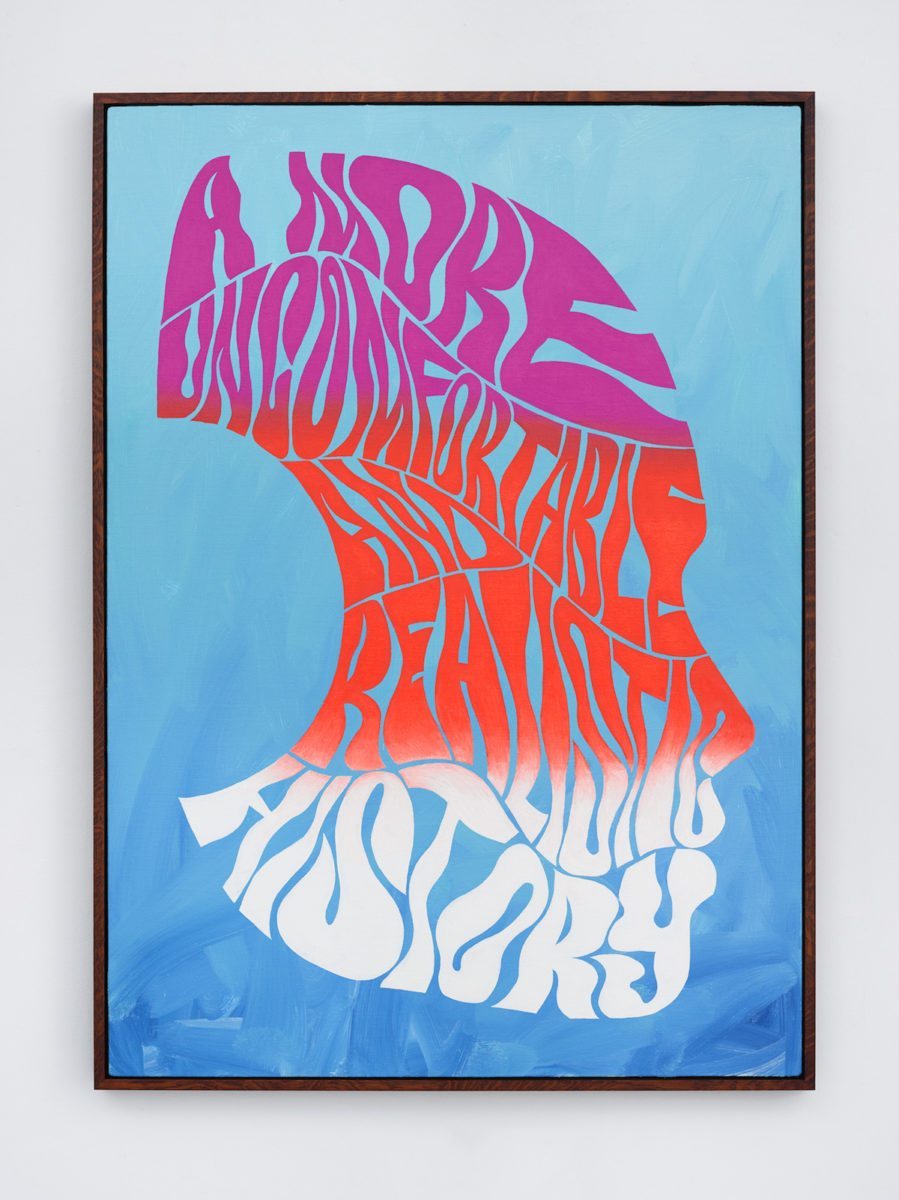

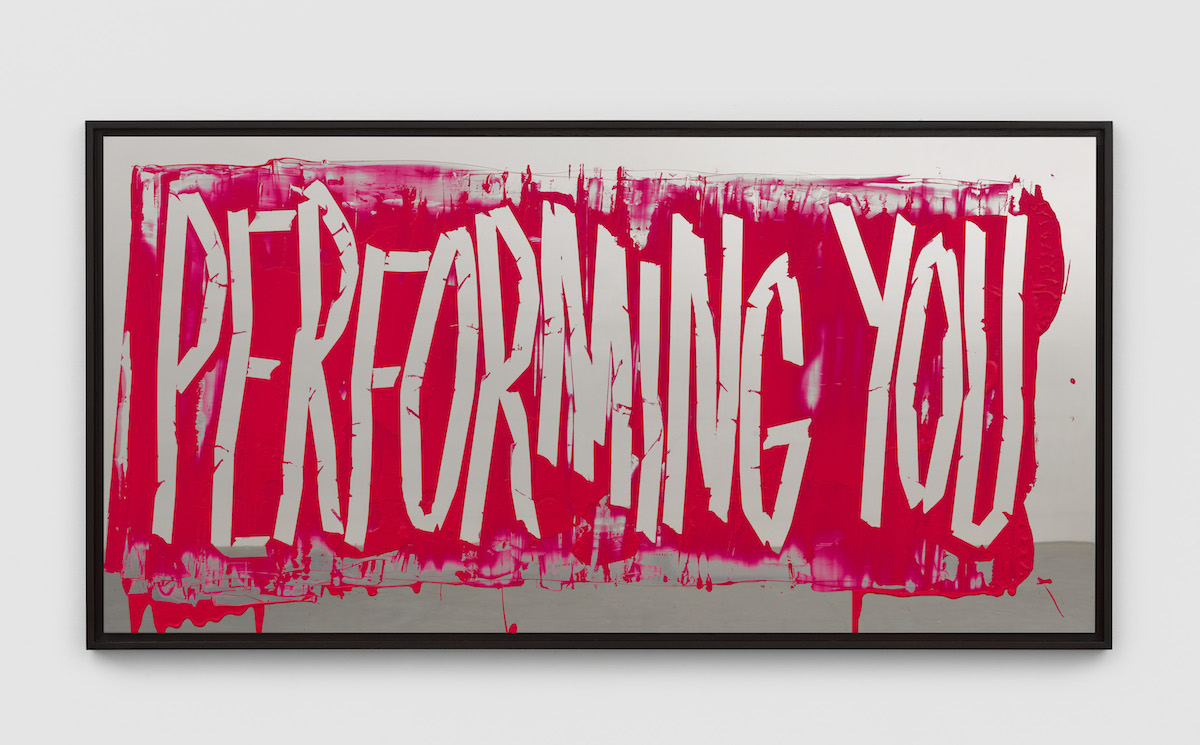

- Left: Eddie Peake Autoritratto Tre, 2017. Right: Eddie Peake A More Uncomfortable And Realistic History, 2017

Peake’s approach is an associative one, scattering objects bought on Stroud Green Road amidst brightly painted canvases with large-lettered words that seem to shout from the surrounding walls. “A MORE UNCOMFORTABLE AND REALISTIC REALITY”, reads one, “PERFORMING YOU” another. These text-based works seem to acknowledge the inevitable challenge of representing the everyday-ness of regular life in the echoey, pristine shell of the gallery, and of “performing” reality. I am curious about Peake’s take on the often undemocratic nature of the art world and its exhibition spaces. “It’s interesting, because I think there can be a lot of snobbery around art or exhibitions that do step into a public conversation. For my part, I find that possibility really exciting, and a gallery like White Cube is really well positioned to be able to facilitate that, because the people that come here, by my observation, include people who are going to ten different exhibitions a week, who live and breathe art, right through to people who have been to London Dungeons and Borough Market and they think, ‘Oh, let’s go to this gallery as well’—and everything in between the two. I really like that because it means the conversation I can have is both an esoteric, advanced, expert conversation, and one that affects real people’s real lives.” He pauses before adding: “I’ve always said, I want my work to exist in the world and not just in the art world, because the world includes the art world, but the art world often doesn’t include the world.”

The immersive, crowded and multicultural nature of the city is present at every turn in the exhibition, and to traverse the space is a suitably multi-sensorial experience. Music from upturned speakers pulses through the gallery, while pink and blue hair gel squeezed out onto metal trays smells sickly sweet; a pervasive pink glow illuminates the room, altering the tone of visitors’ faces with a subtle, mind-altering effect akin to that of the artificial strobes of the nightclub. DJs from Kool London, one of the longest running London-based underground stations, are broadcasting jungle and drum and bass, an important influence on Peake during adolescence. “I think there’s something similar in the way that people experience radio to the way people experience public spaces as a community, which is that it’s very democratic, you can be anyone and the radio is for you,” he says of their inclusion in the show.

“The world includes the art world, but the art world often doesn’t include the world”

I ask Peake about the highly personal nature of the exhibition. I see it as reflective of the idiosyncratic and completely individual relationship that we each have to our own home city, filled with memories, favourite places and routine. “Exactly. It’s a very personal experience, but it’s not exclusive to me. It is about north London, and at a very direct level it’s about the concrete pitch in Finsbury Park. But I see that as microcosmic of London at large. So in a way, it is about London, but then it’s also just about people.” For Peake, the gallery becomes a place for anyone, from all walks of life, to congregate, much like the concrete pitch of his childhood. “I want people to come to the show and enjoy it as well. I think it does have a recreational feeling about it as well: there’s lots of spaces to go and explore, lots of different ways of experiencing the work.”

We are almost out of time as the gallery is shortly to open for the day, and Peake must resume his routine performed within the space. We exchange memories of our own teenage years in London, and Peake mentions Zadie Smith, perhaps the contemporary writer most closely associated with London, known for her ability to peel away the layers of the city and reveal the human rhythms within. He is a fan of NW, titled after the north-west London postcode in which it is set: “It’s the only Zadie Smith book that I have read, and I really liked it because of its description of areas that I know so well.” Even as we reminisce—“I went to secondary school in Tufnell Park, so a lot of my experiences as a teenager were those extended bits of north London that she’s describing in the book”—Peake is precise when defining his attitude to the past: “One thing I want to be careful about is that this is not a show about nostalgia.” Instead, he sees the exhibition’s evocative reflection of the people, society and culture, of his neighbours and community, as something to be taken forward for the future. In an age of growing political and social division, it is an important message of inclusion. “It’s about memory, but for me it’s about using my memories of that time as a model for how to think about things today,” he concludes, before heading back out into the gallery: “I better get back to it.”