Edgar Martins’ work with HMP Birmingham inmates is a thoughtful, original take on its inherent prison theme. “I wanted to convey the hidden stories, talk about the difficulty of working in these sort of ethically charged environments, and think about the role that photography plays in the portrayal of prison and incarceration (which I am generally very critical of),” the Portuguese photographer says.

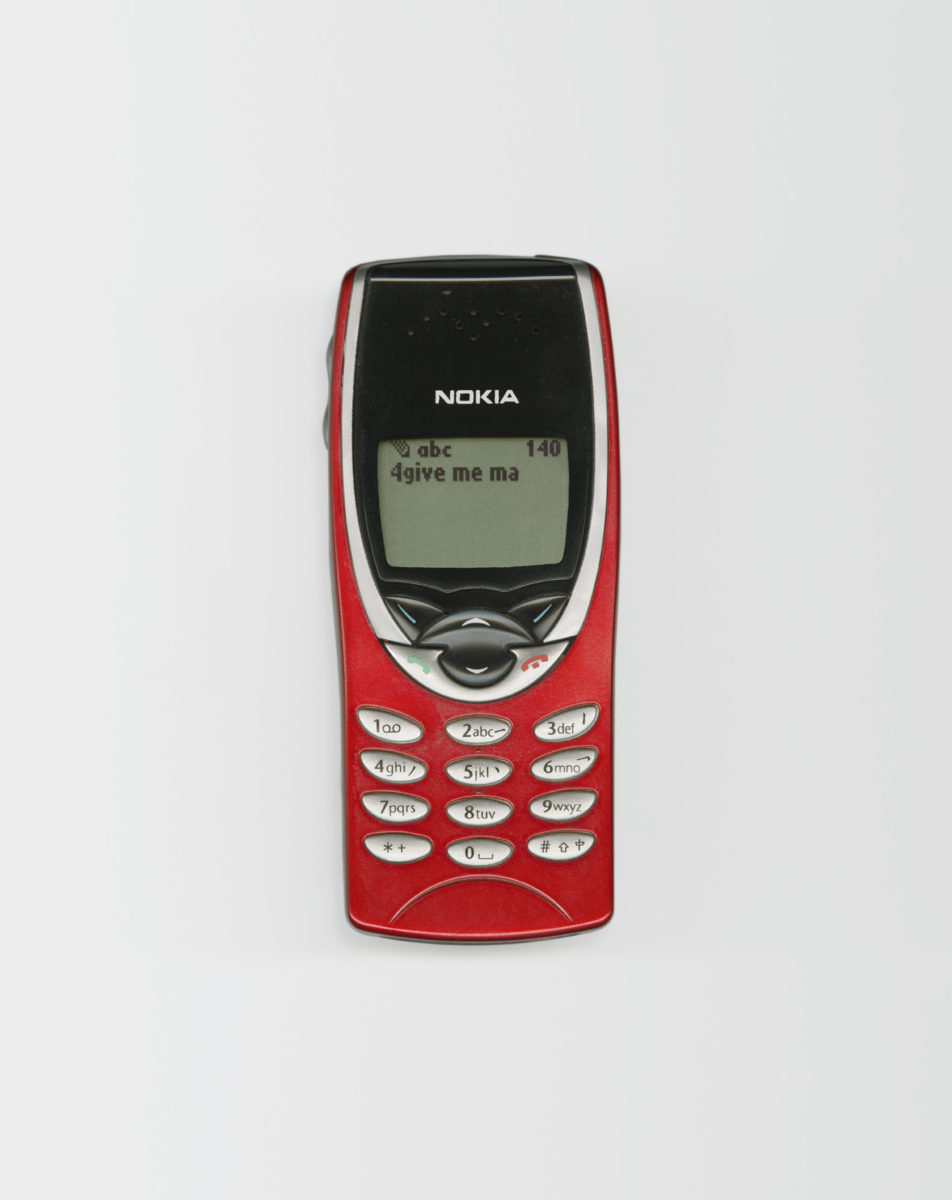

His recently launched series was created in a collaboration with inmates and their families, which lasted for more than three years. Martins would meet them in their cells during visiting days and legal appointments. Having established a relationship with the inmates’ families, he would then meet them in their homes, “often becoming a conduit between the inmate and the family”, he says.

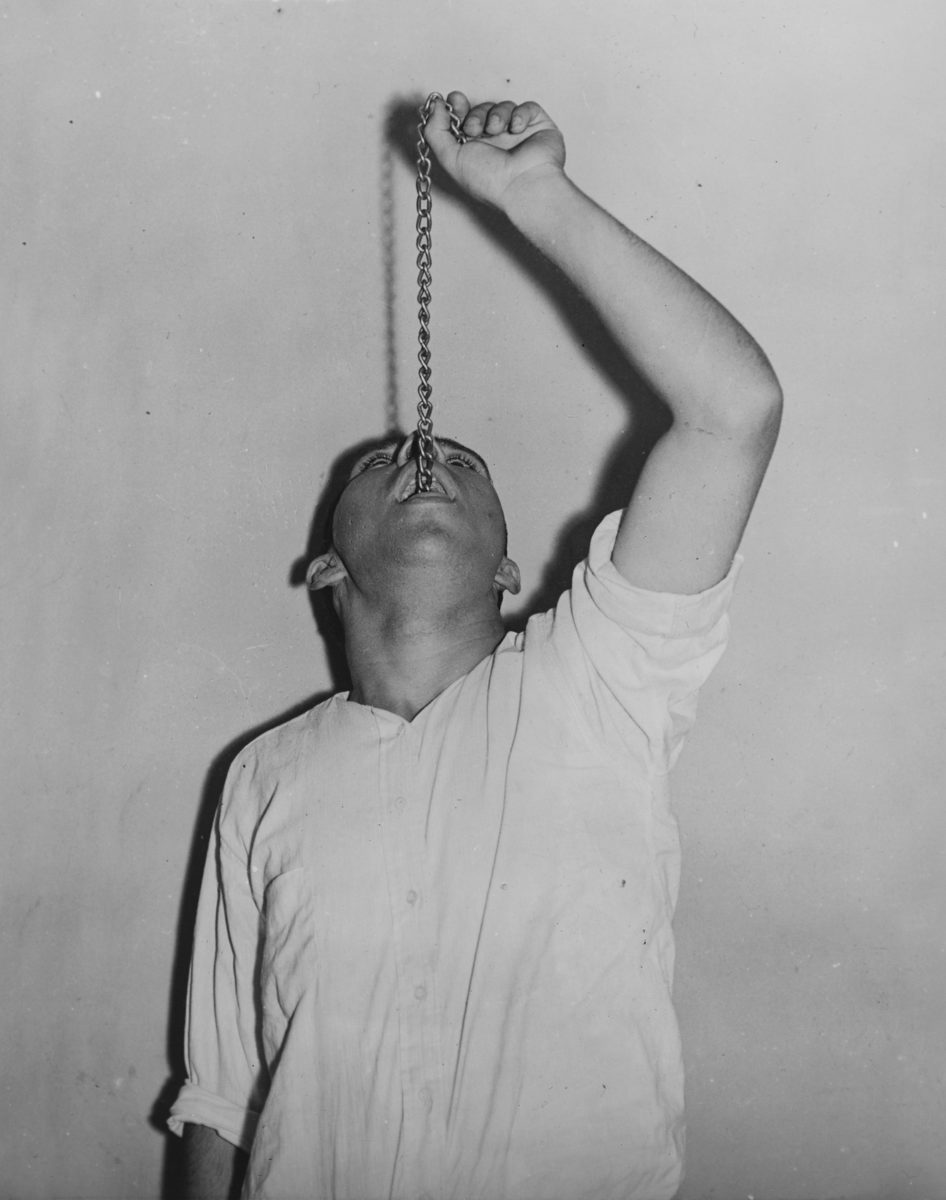

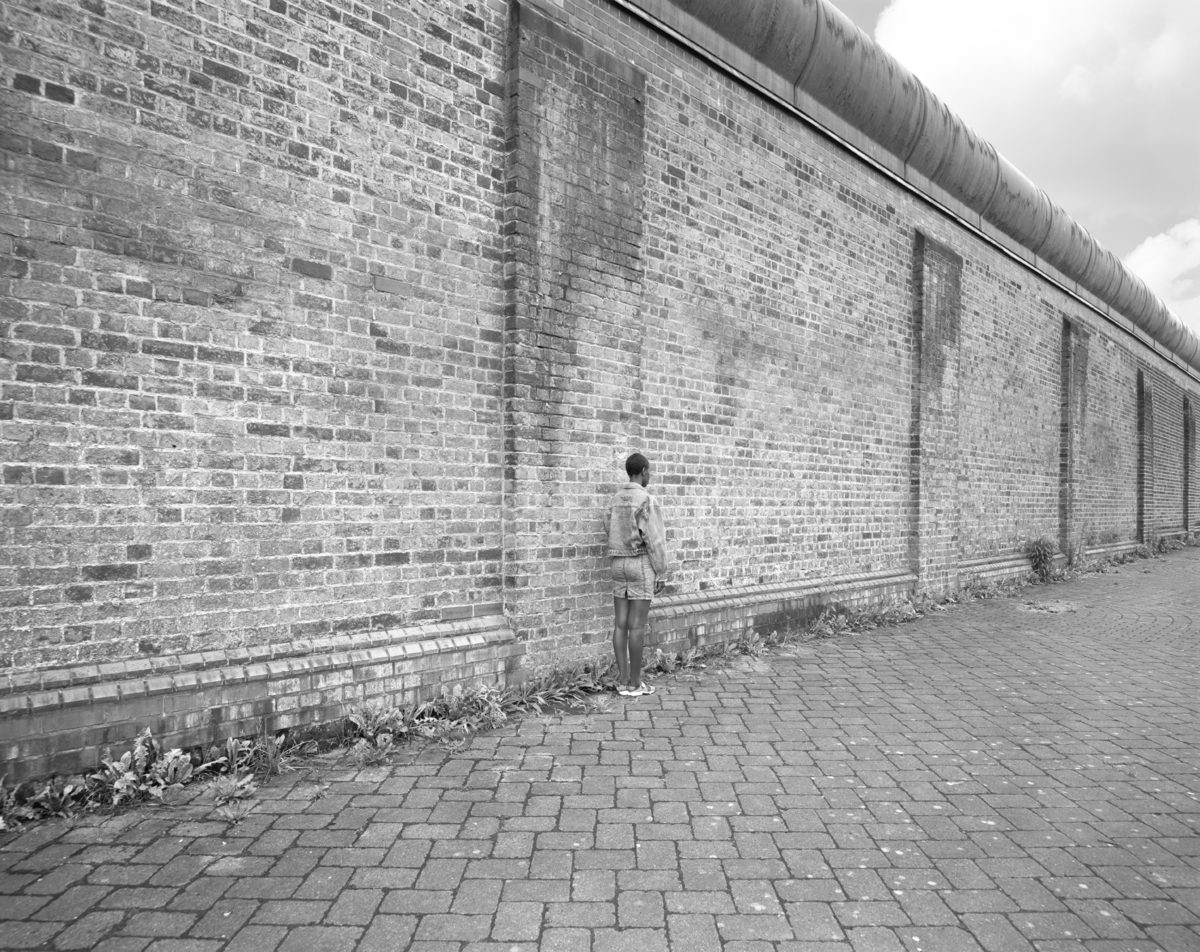

As part of his process, he photographed offenders, ex-offenders and their relatives; he also photographed people enacting their stories. In the final images, no one can be sure exactly who is being depicted. As Martins explains, “this was a way for me to disrupt the power relations and the voyeurism inherent in the consumption of this type of imagery.”

“I went to great lengths to avoid images that just perpetuate the narratives we associate with prisons: race, drugs, criminality, violence”

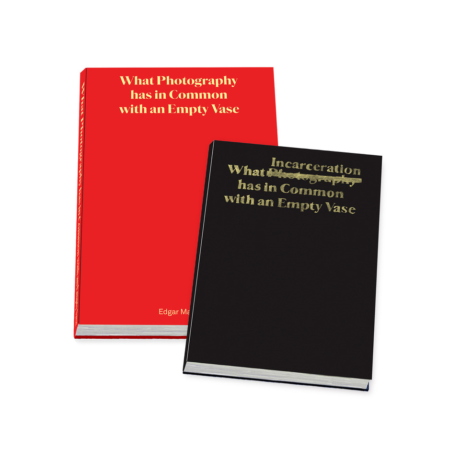

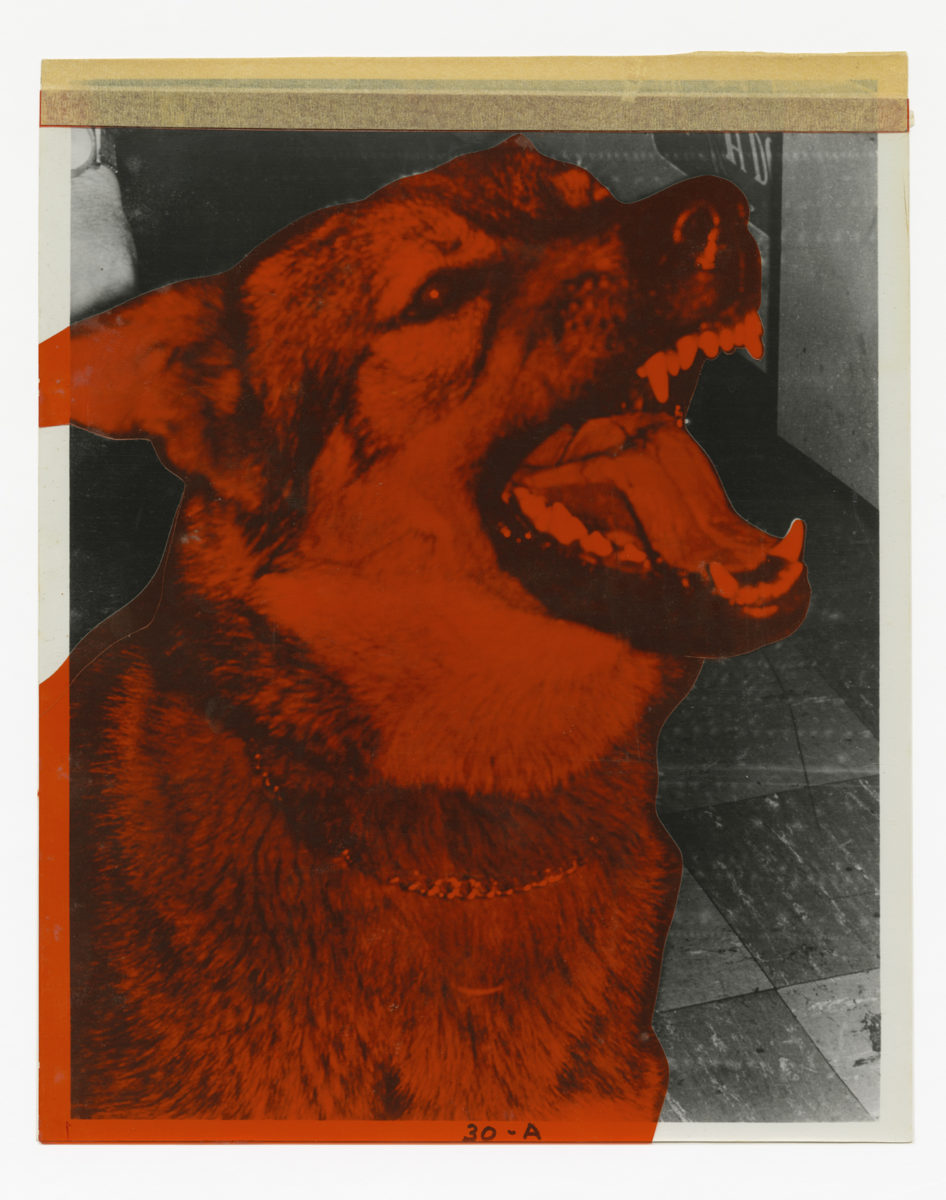

The result of this project is an exhibition and book entitled What Photography & Incarceration Has in Common with an Empty Vase (the name is a Lacanian reference). The images are, as Martins has articulated, not the usual sort of visual material associated with incarceration. Instead, he describes them as an act of resistance. “Although I was working with the prison, I decided early on I would not photograph inside,” he says. “I went to great lengths to avoid images that just perpetuate the narratives we associate with prisons: race, drugs, criminality, violence.”

Throughout the project he worked with a number of organisations and individuals local to the prison, including youth centres, charities, colleges and universities, some of which were associated with the prison, some of which weren’t. His final images are, he says, “very much a collaboration”: they represent and sometimes enact the inmates’ stories, and Martins’ subjects directly influenced how the photos were made, through genuine involvement in the project throughout.

“In an era of fake news, how can we best acknowledge the imaginative and fictional dimension of our relation to photographs?”

His technical process was also unusual compared to many documentary-like series. “I don’t work like a traditional photojournalist in the sense that I don’t walk around with a small 35mm camera snapping what I see in front of me,” he says. Instead, he works with 8×10 plate cameras that are similar to those in use a century ago. “There is a reflexive, constructive and performative element to all the images, even if most are not artificially created or staged,” he adds. “It is both a social and community based project but also an anthological study on the role of photography.”

While the starting point of the project was firmly rooted in exploring the social contexts of isolation, this took on more conceptual meanings as Martins explored the philosophical concept of absence, and life’s intrinsic tension between revelation and obfuscation.

“From an ontological perspective, I was interested in questions such as: how does one represent a subject that is absent or hidden from view?” says Martins. “Photography for so long has been defined by a relationship with the subject it purports to represent. So what does it mean for photography if it does not identify with the its subject but its absence? Can absence be a form of activation? Moreover, in an era of fake news, how can we best acknowledge the imaginative and fictional dimension of our relation to photographs?”

What Photography and Incarceration Has in Common with an Empty Vase

Until 18 April at Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry

VISIT WEBSITE