Courtesy the artist and Ikon

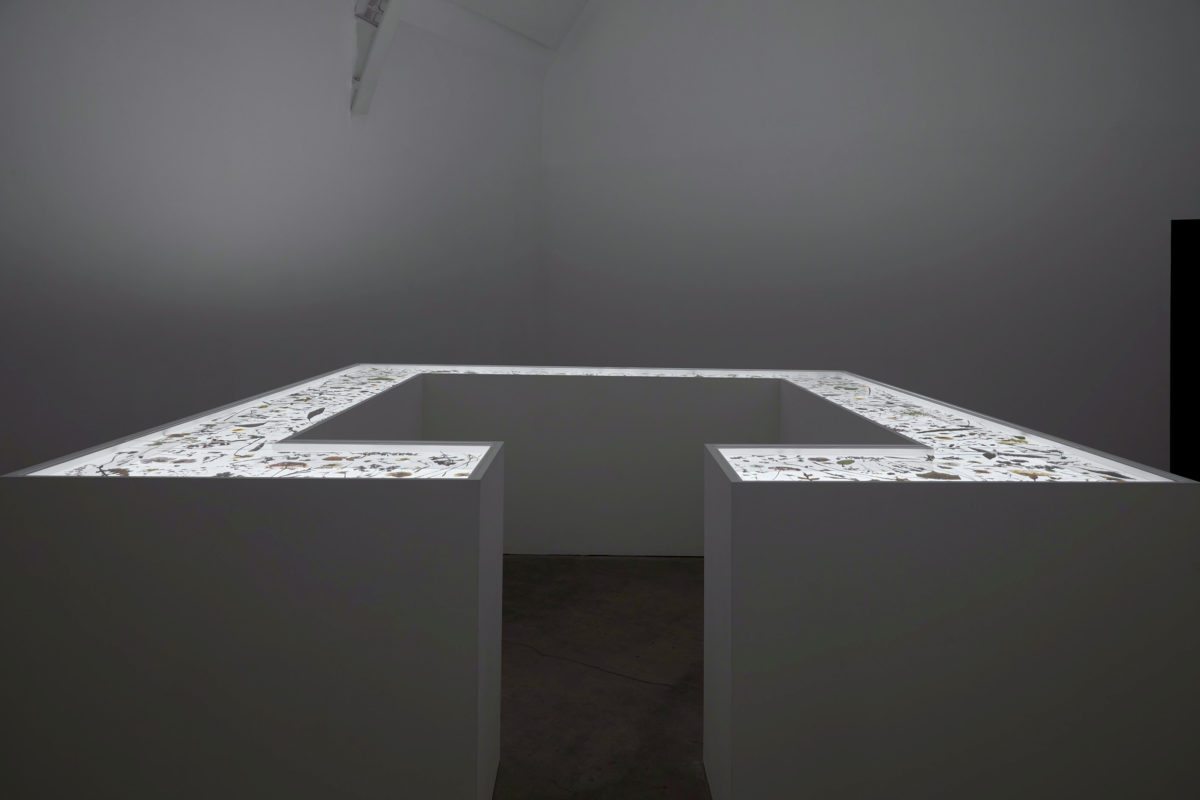

In the first room of Edmund Clark’s exhibition at Ikon Gallery, a low white wall demarcates a small rectangular space. Built into the top of this wall is a lightbox layered with an array of pressed wild flowers. It’s a delicate vision until you realize that the cramped space outlined is the exact dimensions of a cell within HMP Grendon, the prison at which Clark has been artist-in-residence for the past three years. The flowers were picked within the grounds by Clark and inmates, and pressed using prison-issue paper towels. In Place of Hate is a culmination of the work from this three-year residency in Europe’s only wholly therapeutic prison environment.

The average stay at Grendon is around five years, and the prison is specifically for those who have committed serious violent and sexually violent offences. You have to apply to be referred there and, of course, not everyone is accepted. Residents undergo a thorough therapy programme. At a time when most prisons in Britain are overcrowded, understaffed and dysfunctional, Grendon is out of the ordinary.

- Edmund Clark, 1.98 m2, 2017, In Place of Hate, Ikon Gallery. Photo by Stuart Whipps, courtesy of the artist and Ikon

Although Clark is a photographer known for his exploration of hidden systems of control and conflict, most famously in the project Guantanamo Bay, If the Light Goes Out, this exhibition features no printed photographs. Instead it is a series of installations using still and moving images, projected onto prison bed sheets or screened in a circle of prison chairs.

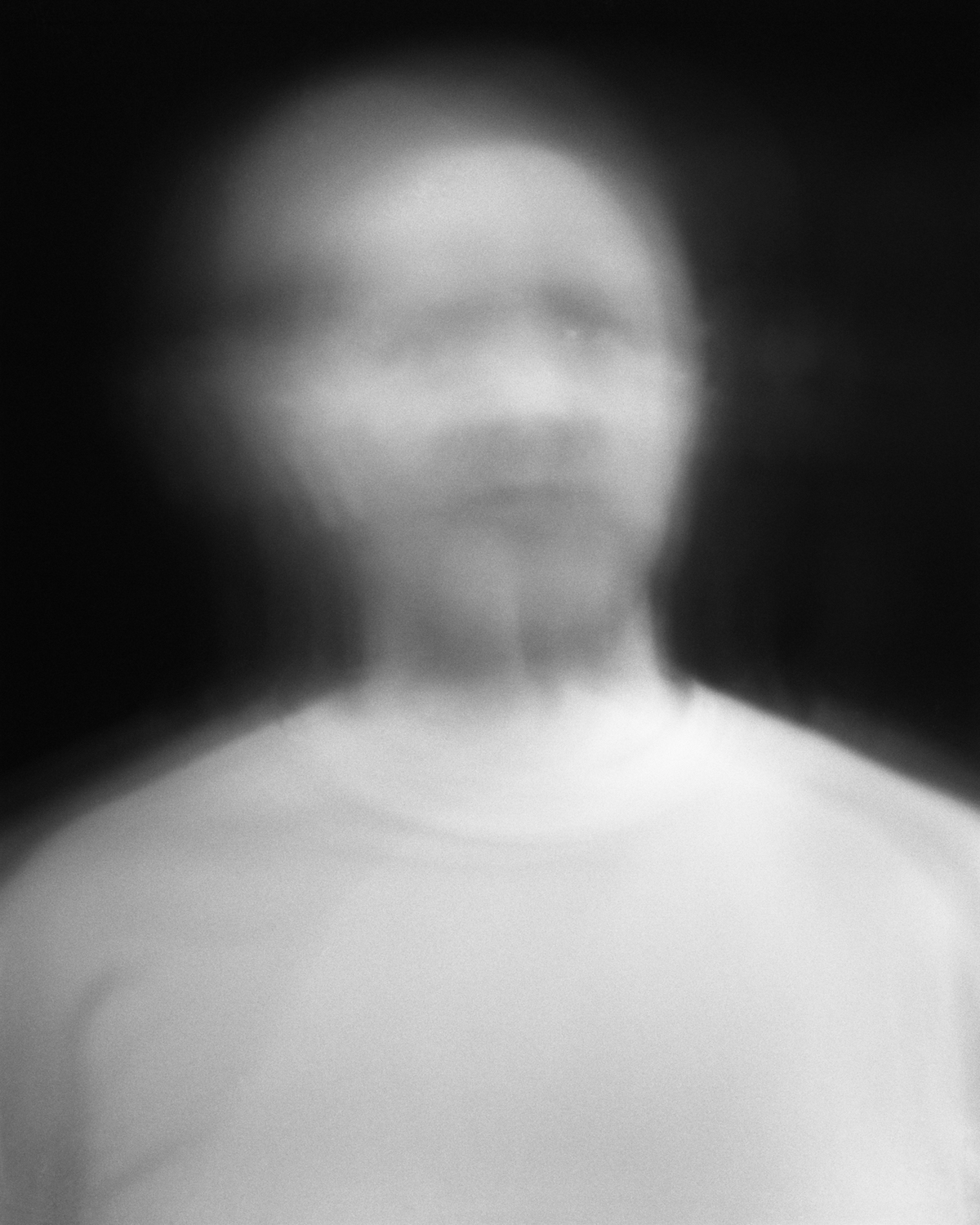

Whilst he worked to make many of the images with Grendon residents, Clark was not allowed to show their faces in any recognizable way, getting around this by using a pinhole camera to capture the ghostly shapes of inmates as they spoke. Even those wearing masks during an enactment of The Oresteia (psychodrama is one of the main creative therapies available in the prison) have had to be pixelated, and although hard to avoid, the warped and masked faces don’t do much to challenge perceptions of those behind bars as inhuman monsters.

The work asks the contemporary art audience to at least consider what is behind high walls, that which is easily and all too often ignored—and to recognize their freedom to enter, move around and leave the gallery space, to engage and disengage with these lives of incarceration as they choose.

You’ve worked in Guantanamo Bay, you’ve worked in the Kingston prison in Portsmouth. What is it that draws you to those places of incarceration?

The work I’ve done about Guantanamo Bay, terrorism suspects, control order, is different to the work I’ve done actually about incarceration in Britain. Those are about unseen processes of contemporary conflict.

The work specifically about British prisons—Still Life Killing Time, My Shadow’s Reflection and In Place of Hate—is about how we lock people up; why we do it and where we do it is really important. It reveals an awful lot about us and our society. Incarceration and trying to make it something that people talk about, trying to show it in a different way, is important. There is very little discourse around criminal justice, what there is is very poor and uninformed. So it’s important to try and do work which brings this subject closer to us. And it is “us” and “them” in this relation—it’s very easy to have this binary understanding about crime and criminals, and that’s a very reductive position to be in, it doesn’t foster understanding or any attempt to engage with why people do these things. Until that happens, rehabilitation is probably never going to be on the agenda in a suitably meaningful way.

You went into Grendon as an artist. How did you deal with having that different power relationship, where you weren’t a “convict”, but you were going in there to work?

Carrying keys is an interesting experience. When I worked in the prison for Still Life Killing Time, I didn’t carry keys because it was a discrete space. Carrying keys is quite oppressive, you have so many doors and gates to open. You constantly have this jangling thing in your hand and you keep turning locks all the time. Psychologically there is a huge pressure not to leave one open, which I have done once, and it brings its own paranoia. Unless I can visualize in my mind having locked a door, I will walk all the way back down the corridor to check.

The relationship with the residents: there’s clearly an imbalance because I go home at the end of the day. I can let myself out, they can’t. Collaboration is the wrong word because collaboration presupposes a sort of equilibrium, and I don’t think that equilibrium really exists in the work I’ve made. With the men I’ve explained what I’m trying to do in the work, where I might go, the reasons I’m doing it and what I want from them. Some people didn’t want to do it, but a lot of them have and they’ve engaged with it. But, at the same time, they don’t have real control over what happens to their work. So, it’s not an entirely equal relationship, but certainly it has been shaped by their engagement.

Courtesy the artist, Ikon and Flowers Gallery

Did you build up relationships with individual residents there?

Yes, definitely. Part of the work I do is also facilitating their own practice. Monday or Tuesday night I’ll go onto A wing and sit down with a group of people. I worked with some people over all three years I’ve been there, so yes you do develop relationships with them. I think that’s part of the point of what I’m doing as well, having someone from the outside who has their own creative practice—seeing what I do hopefully informs their own practice and we can understand each other, and that’s part of its point.

It can be strange when people leave. The first people I worked with for a long period of time left, and it was quite strange dealing with their absence because it changes the dynamic on the wing. These are very much communities and there’s a balance within those communities: they go up they go down, they fragment, they come together, and the dynamic with the groups I work with really does change.

“Whilst it’s an incredibly democratic place, there is this constant undercurrent of trauma.”

You’ve had an exhibition in the Imperial War Museum as well, but this is a contemporary art space. How do you think that changes the way it’s received, and what do you prefer?

I think they have different but equal challenges and opportunities. With the Imperial War Museum exhibition I was working with the head of photography and the head of art. We dressed that exhibition trying to make it contemporary. It wasn’t a museum exhibition, it was still an art exhibition within a museum. Having said that, the nature of the audience is different, so the way in which the work was contextualized in some cases had to change, for a wider museum audience.

With all the work I do, I have a number of different platforms and different audiences, so for each you’re thinking about how they might expect to see the work, what they might know about it, what challenges you can give them, what information, what context you need.

I set out to make work here that is as installational as I could, and I probably have more freedom in terms of how I do that than I did in the museum. It’s a mixture of video work, projections, performance pieces, furniture. I brought as much as I can in from the prison environment. The chairs are from Grendon, the sheets are the sheets from Grendon… which I washed in my own washing machine.

Photo by Stuart Whipps, courtesy the artist and Ikon

Did your own views of the prison system change during your three years working there?

Having worked in prisons before, I was predisposed towards rehabilitation. I have more experience of prison and more understanding of how rehabilitation within a prison environment works than the vast majority of people who’ve never been inside, but Grendon still took me by surprise. It’s a unique environment, an incredibly intense place, unlike any prison I’ve been in before, where you get a community spirit—Still Life Killing Time was a particular community—but it’s a merging of the community experience with therapy, and the community experience as part of the therapy, and people’s behaviour in one informs what happens to them in the other.

In some ways it’s incredibly utopian, but it’s also a really challenging environment for them to live in. They have to be held to account at all times for their behaviour, they have to control the way they behave, the way they respond to other people. They have to deal with how they’re feeling and listen to what other people have done, what’s happened to them. They have to go back into their own lives and share that, and that’s a very difficult thing to do. While it is an incredibly democratic place, there is this constant undercurrent of trauma, I think. I don’t know if they would describe it that way, I get the impression they would, but I’ve certainly felt that. This work is my personal response to that. Not only is there trauma in terms of what people are sharing about what they’ve done, but also the experience of living in that kind of environment where you are held to account for your behaviour all the time is a very traumatic thing.

Courtesy the artist, Ikon and Flowers Gallery

Edmund Clark: In Place of Hate

6 December until 11 March 2018 at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham

VISIT WEBSITE