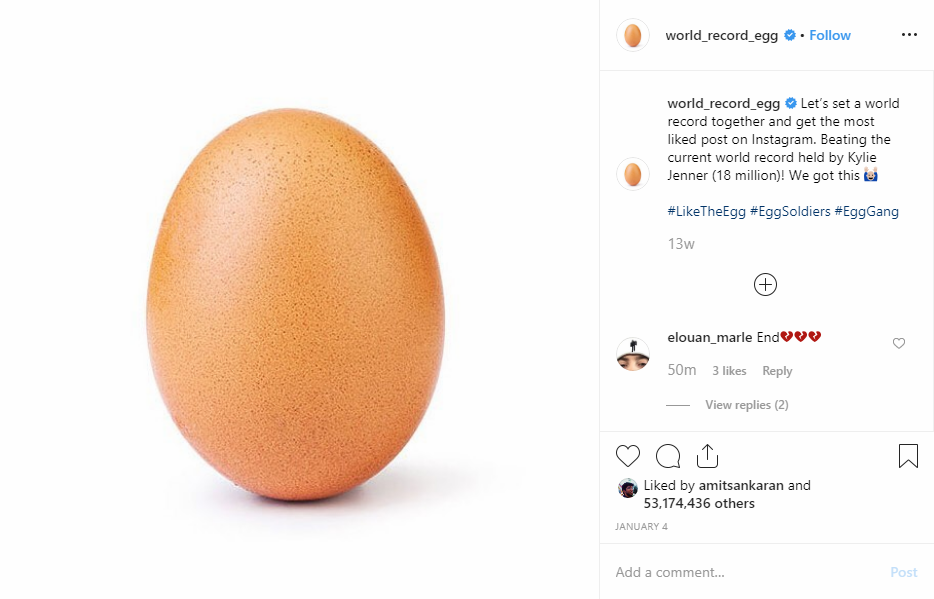

Even as our society heads inexorably towards mass veganism, the humble egg still has a firm grip on our aesthetic imaginations. This was proved earlier this year when an almost offensively generic egg (@world_record_egg) became the most liked image on Instagram, beating out Kylie Jenner’s image of her and new newborn child and subsequently attaining something like influencer status; doing paid partnerships and promoting social causes. It was the brainchild of advertising creative Chris Godfrey, who said he chose the egg because it’s “simple and universal”, and has no gender, race or religion. But perhaps there’s more to the egg’s stratospheric popularity. The most liked image on Elephant magazine’s own Instagram account is of Christopher Chiappa’s 2015 installation Livestrong, in which thousands of fried eggs cover the walls, floor and ceiling of the gallery, creating a visual so strong it’s practically synesthetic. Clearly, there’s something about eggs.

“To a human eye the egg has many attractive features: its tapered shape gives the impression of being grounded where a simple sphere always threatens to float away”

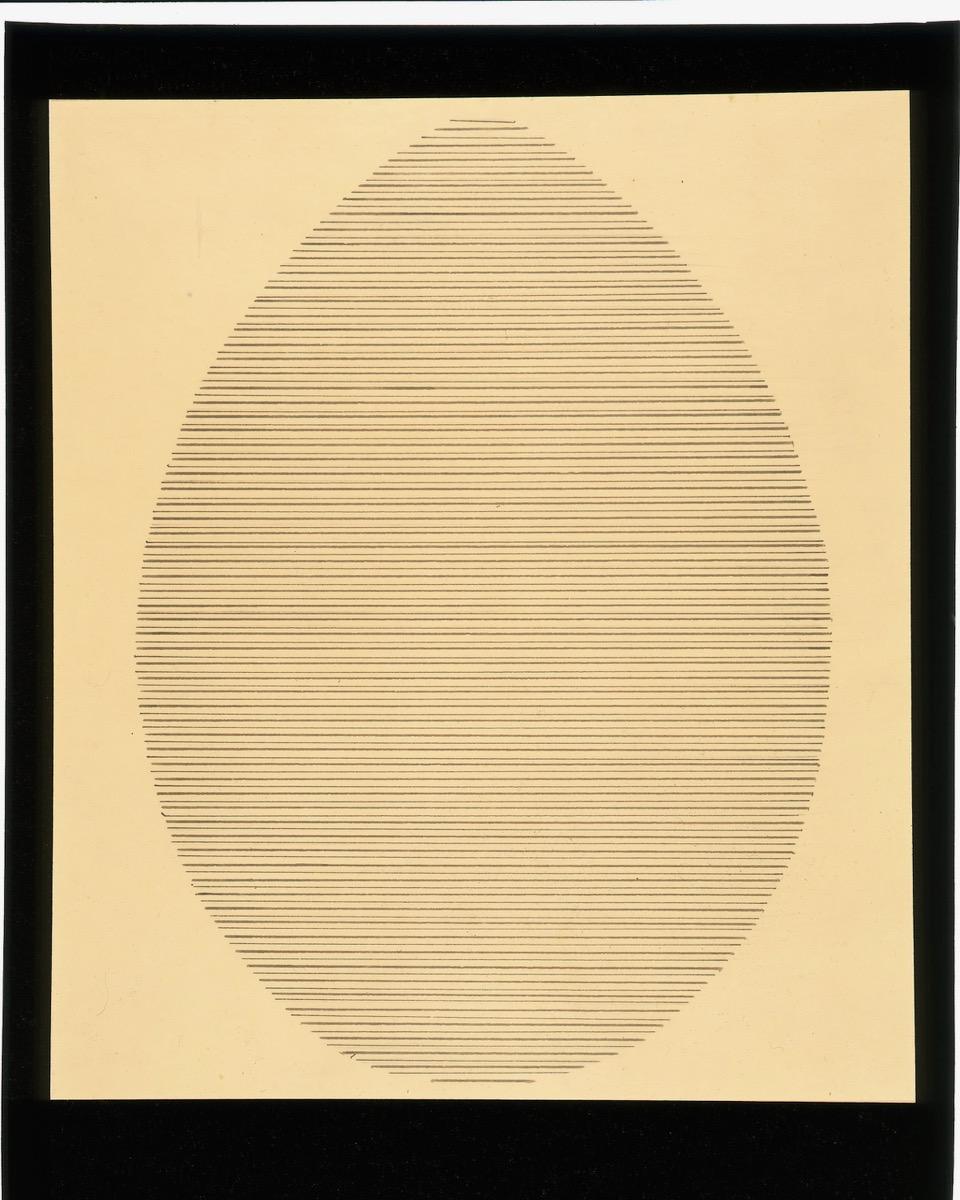

According to perceptual psychologists the brain likes visual simplicity, balance and the impression that something is contained. To a human eye the egg has many attractive features: its tapered shape gives the impression of being grounded where a simple sphere always threatens to float away; its smooth curves are the antithesis of hostile or edgy; and there’s something comfortingly complete about it. Meditative minimalist painter Agnes Martin, who considered her works expressions of calm but profound joy, occasionally abandoned her usual squares to experiment with egg-shaped works, filling the symmetrical ovoid with her delicate lines.

A “fried” egg has its own attractions. The bright yellow of the yolk is undeniably joyful, and it’s contained within a defined field of neutral white—playing out the figure-ground relationship that forms the backbone of how we process visual information. A nice fried egg is formed of curves, containment and completeness. Unless you break the yolk or smash the shell of course. Then it’s just violent. Urs Fischer, preoccupied as always with entropy and playing in the pop culture sandbox, designed an album cover for the Yeah Yeah Yeahs on which a hand explosively crushes a raw egg, goop flying out sloppily. Fisher, who is very fond of using eggs in his work, balances the viscous “yuck” with the sharp shell and the angry clenched fist.

- Urs Fischer, (left) Half a Problem, 2013, photo by Mats Nordman © Urs Fischer. Courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ; (right) Problem Painting, 2013, photo by James Ewing © Urs Fischer. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

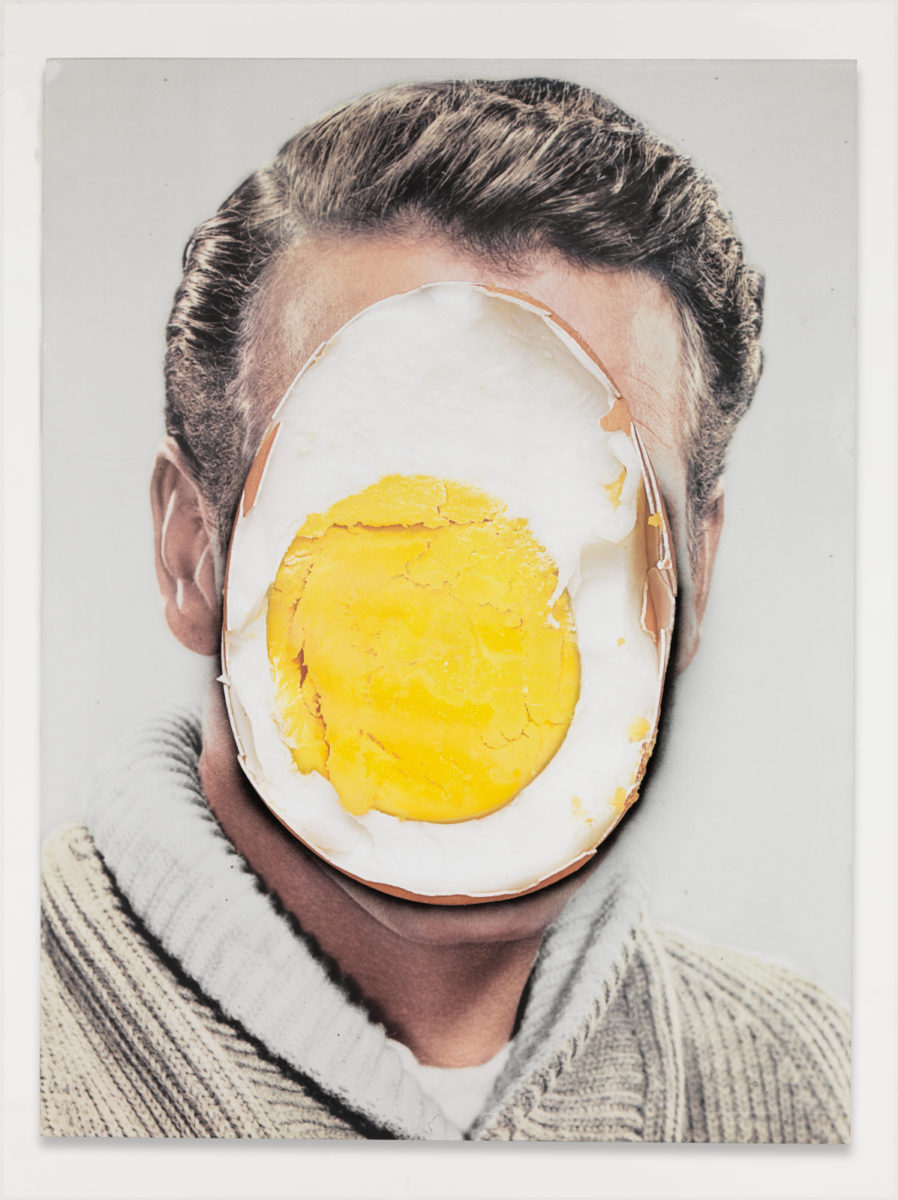

Perhaps another reason we’re so drawn to the egg is its similarity to the shape of a human face. There’s something oddly existential, for instance, about the fact that clowns claim their official “persona”, by painting their exclusive “face” on an eggshell which is then kept in an archive for reference—a process which is mercilessly inverted in Fischer’s Problem Paintings series, in which an old Hollywood headshot has an egg—whole and smooth, cut in half, cracked or just raw—obscuring the face. Clowns are a good reminder that eggs are also inherently funny, and just a little bit gross. There’s something so undignified about them, whether they’re flapping around on a spatula on the way to a plate, or being smashed over the head of an offensive politician.

Claes Oldenburg, whose pioneering pop “soft sculptures” irreverently explored commodity and consumption in the 1960s, was also a fan of the egg. His inflatable Sculpture in the Form of a Fried Egg (1966/71) was his largest experiment with the floppy, flappy fried-egg form. For Oldenburg, a great deal of the egg’s appeal lay in its unsophisticated mundanity—the closest eggs come to sophistication is being whipped into meringue, and even that is frankly verging on camp. From the soft fabric Fried Eggs Under Cover (1962) to the hard plaster Fried Egg in Pan (1961), Oldenburg was repeatedly drawn to the breakfast icon throughout his career, just as he returned to lipsticks and vacuum cleaners and other domestic objects, playing with scale and substance in an endlessly subversive game.

“A nice fried egg is formed of curves, containment and completeness. Unless you break the yolk or smash the shell of course”

Oldenburg wasn’t directly examining gender in his exploration of the domestic and the commercial, but the egg has, unsurprisingly, also been a popular motif for a host of decidedly feminist artists. From Vicki Hodgetts’s Eggs to Breasts installation on the walls and ceilings of the Womanhouse (1972) kitchen, to Sarah Lucas’s equally on-the-nose and equally complex Self-portrait (1996) with two fried eggs plopped on her chest, female artists have reclaimed the egg from centuries of patriarchy-coloured fertility metaphors.

Unpacking the idea of an egg is an ongoing task for a new generation of artists like photographer Heather Glazzer, busy queering feminism and exploring sex and gender in a new reality. Glazzer’s egg-and-bubble-wrap cyborg may subvert the biological assumptions that underpin many egg-related ideas, but like hundreds of artists before her she clearly delights, on some level, in the egg’s varied visual potential.

Salvador Dali, Egg at the Dali Theatre Museum. Copyright-free image via MaxPixel

So it seems the egg is here to stay, flashy “chocolate avocado” stunts notwithstanding. Its symbolic riches are apparently inexhaustible, and its algorithm-conquering appeal ought to ensure eggs, and egg artworks pop up in our feeds with reassuring regularity, sure to inspire a like or two above the average. Why? Premier portraitist of the human psyche Salvador Dali, who crenelated the walls of his museum with huge, anxiously balanced eggs (and also enjoyed eating and painting them), thought they were the perfect symbol for everything from eyes to rebirth, to the world and its perfection. So maybe the creator of @world_record_egg was right; perhaps there is something truly universal about an egg.