To accompany The Villain of History for One Night Alone, his current solo exhibition at Pilar Corrias, Sedrick Chisom shares a selection of the books that have shaped his oeuvre.

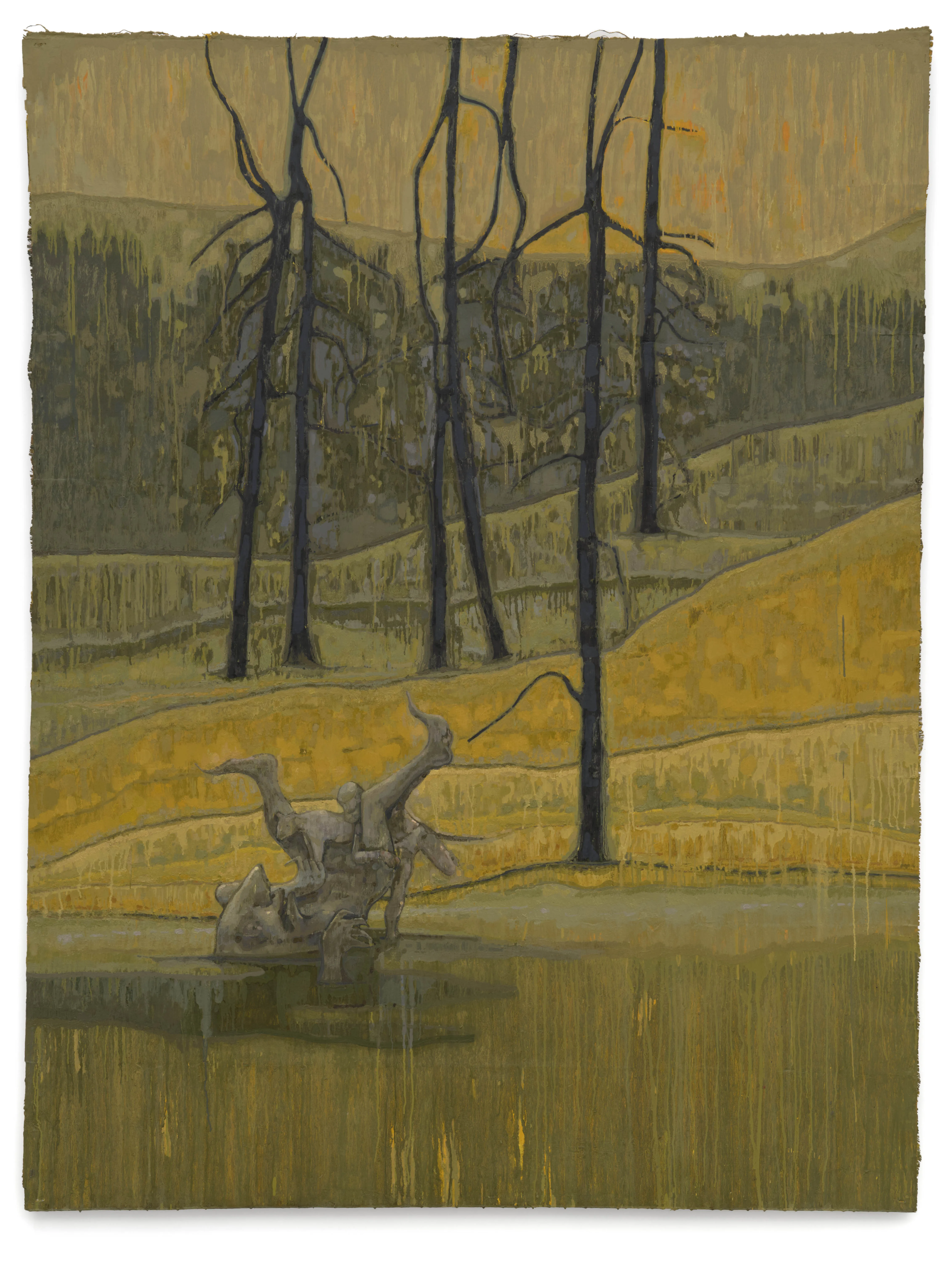

Sedrick Chisom’s paintings are vivid and otherworldly, rendered in acidic palettes that depict a dystopic world on the edge of reality. His works form a complete artistic universe, rooted in his yet-to-be-produced stage play, 2200, a dark-magical-realist parable which imagines the departure of people of colour from planet Earth in search of better worlds.

Chisom’s paintings visualise the world established in the play and are presented with long, poetic titles that offer miniature narratives told from the perspective of an omniscient onlooker—not unlike short stories, or the voice of a science fiction film narrator. One painting in his latest exhibition at Pilar Corrias, for example, is titled They had Smelt It In The Air and Confirmed that The Enemy could Wipe out a Hundred Thousand of Them at Once, but Their Thoughts Turned To The Day They Would Ice Skate Together.

Literature beyond his own writing is also a major source of inspiration for Chisom’s paintings. Below, he discusses eight books which have influenced his artistic practice; spanning sci-fi, speculative fiction, intimate letters, and psychoanalytic writings, his selections offer insight into the foundations of his world-building practice and the stories revealed through his paintings.

Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

Crime and Punishment (1866) by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, renowned for its psychological depth and exploration of morality and guilt, was a formative read for Chisom as a teenager. He explains, ‘Crime and Punishment was the first book I read on purpose, when I was 14. It’s about a society conflicted by a collision of both secular and non-secular values. They’re in an in-between period of cultural and economic development, where God exists, but they also understand values as socially constructed. The main character is a Marxist who believes morality is a construct of the economic base. He kills his landlord, thinking he’ll redistribute her wealth, but he can’t bear the guilt. I was interested in this morality play and its questions about nihilism.’

Parable of the Sower (1993) by Octavia E. Butler

A dystopian science fiction novel by canonised author, Octavia E. Butler which exemplifies her blend of speculative fiction and social commentary, engaging with themes of environmental collapse, inequality and the power of belief systems. For Chisom, ‘it conveys really complicated ideas, but in an aesthetically delivered form, almost like a teen novel. There’s an accessibility to it and a visionary quality. It was initially conceived as a cautionary tale, and that’s a direct inspiration for my work.’

The Monstrous Races in Mediaeval Art and Thought (1981) by John Friedman

A study of how medieval European culture depicted “monstrous” peoples—legendary human-like beings thought to inhabit the fringes of the known world. ‘It formed the basis for the work I do,’ says Chisom. ‘There were actually moments when I got so excited reading parts of it and I was like, ‘I have an idea. I know what my subject is.’ I refer to it frequently, and I’ve depicted several of the characters from the monstrous races paintings. The whole narrative I’ve written [around my work] is actually a search for the monstrous races. It’s a foundational book for me.’

The History of White People (2010) by Nell Irvin Painter

A critical examination of the concept of Whiteness, tracing its origins and the evolution of race as a social construct over the past two thousand years. Chisom finds it ‘funny’ and ‘absurd,’ explaining how Nell Irvin Painter ‘looks at the idea that there is a group of people called White people, which we know is modern, and she’s looking for a mythological origin of that. Where do the terms come from, like Caucasian and Aryan? Where do certain beauty standards come from? Where do certain notions of a “White character” emerge from? She explores the Dionysian and Apollonian dialectic, the expansion of White people as legal categories in the 19th and 20th centuries, and examines the deep ironies inherent in this.’

Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice: A Treatise, Critique, and Call to Action (2015) by J. F. Martel

Martel’s manifesto offers aesthetic, cultural, and ideological critique, as well as explanatory power, for understanding why culture is the way it is and what is at stake. Chisom describes it as ‘a dialectic between art and artifice. Martel understands art as a quality—something elusive and hard to categorize. Art is transcendent; breaking through to articulate reality in a new way, it reflects the larger, romantic goals of art. Artifice, on the other hand, is the condition of advertising and ideology. Propaganda, shoe commercials, stuff like that. He talks about how a lot of art adopts more and more artificial qualities, and how artifice sometimes adopts the conditions of art. The complication of that is really, really good.’

Jack Whitten: Notes from the Woodshed (2018) by Jack Whitten

Published after his death, this book is a compilation of artist Jack Whitten’s private notes, ‘from his time at Cooper Union to his marriage, and when he was encouraged by de Kooning to keep painting through crises. It’s really fascinating. There are anecdotes where you can tell his sociality was so different. Like, he talks about flirting with a white woman, being “too forward,” and then she asks him, ‘How would you feel if I called you the N word?’ and he literally reflects on how he would feel. He really reckons with himself from these experiences. He talks about buying a gun during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and he formulates all kinds of theories about what art should do, what paintings should do, and the musical conditions of painting. He’s a really poetic, passionate guy. Reading that made me realize that it could always be harder. The work, the ideas, and the drive—that comes first, and the discipline of coming to the studio every day.’

Childhood’s End (1953) by Arthur C. Clarke

This Classic science fiction novel imagines humanity’s evolution under the guidance of aliens trying to facilitate a utopian society. ‘It’s a sci-fi novel about the evolution of humanity by a group of aliens who would be understood as angels,’ says Chisom. ‘The childhood’s end in the story is a metaphor for the aliens’ task of incubating and evolving the human race and consciousness.’

Civilization and Its Discontents (1930) Sigmund Freud

Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents is a cornerstone of his psychoanalytic theories, written at the end of World War I. ‘He’s trying to understand how sexual impulses and aggression originate from the id. He sees the id as the inability to fit into the social unit,’ explains Chisom. ‘Up to that point, he had a cohesive theory about psychology, regardless of whether it’s wrong or not, but [in the book] he uncovers his theory of the death drive. That’s when everything unravels for him. The death drive wasn’t about fearing death, but about fearing the loss of enjoyment. If you’re suicidal, it’s because life is no longer enjoyable to you—that’s why it’s possible. It’s about the unending capacity for the individual to undermine their conscious intention.’

The Villain of History for One Night Alone continues at Pilar Corrias, Conduit Street through 21 December 2024.

Words by Alayo Akinkugbe